Counseling parents about safe infant sleep

Counseling parents about safe infant sleeping recommendations is an important step for preventing sudden infant death syndrome. Yet, many providers, including pediatricians, do not give families with infants basic advice regarding the AAP-recommended infant sleep practices.

Reviewed by Michal A Young, MD

Counseling parents about safe infant sleeping recommendations is an important step for preventing sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Yet, many providers, including pediatricians, do not give families with infants basic advice regarding the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended infant sleep practices aimed at SIDS prevention, such as supine-only sleep, no bed sharing, and pacifier use during sleep.1

Recommended: Do parents push sleep problems onto their kids?

According to a survey of 2355 mothers of infants published in 2010 in Academic Pediatrics, 54% of those surveyed said physicians gave them no advice about bed sharing; 73% said they received no advice from their physicians about pacifier use during sleep; and 28% reported getting no advice about having their babies sleep in the supine position.1

The same study found that mothers were more likely to use safe sleep practices when their physicians counseled them about those practices.1

SIDS: Still a big problem

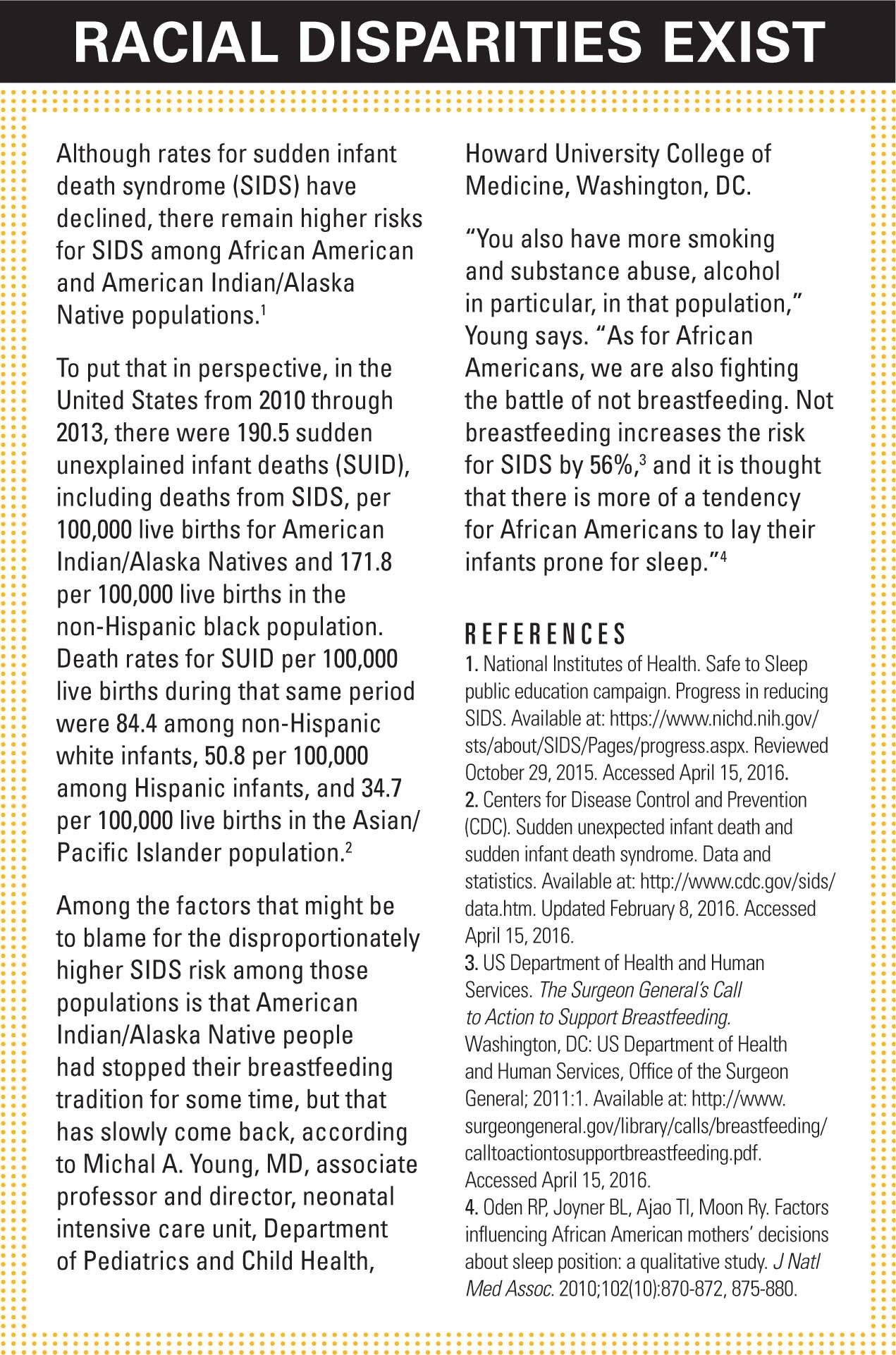

Declining SIDS rates might be partly associated with semantics. Rates for SIDS have fallen from 130.3 deaths for each 100,000 live births in 1990 to 38.7 deaths for every 100,000 live births in 2014. About 1500 infants died of SIDS in 2014, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2

However, other causes of infant death, including accidental suffocation or strangulation in bed (ASSB), appear to be on the increase. Studies suggest that decreasing SIDS rates during the last 25 years could be explained in part by changes in classification of cause of death.3,4

The AAP’s recommendation in 1992 for infants to be placed during sleep in a non-prone position resulted in a major decrease in SIDS incidence. At the same time, however, incidences of infant sleep-related suffocation, asphyxia, entrapment, as well as poorly defined or unspecified causes of death have risen, especially since AAP published its 2005 statement on SIDS.4

Addressing these other related areas has become paramount. The AAP responded by expanding its recommendations to focus not only on SIDS but also on safe sleeping environments, aimed at reducing the risk of all sleep-related infant deaths including SIDS. Authors of a paper on the topic described the recommendations as including supine positioning, use of a firm sleep surface, breastfeeding, room sharing without bed sharing, routine immunization, consideration of a pacifier, as well as avoidance of soft bedding, overheating, and exposure to tobacco smoke, alcohol, and illicit drugs.4

The National Institutes of Health Safe to Sleep campaign makes those recommendations accessible to consumers and providers.5 Campaign terms include: sudden unexpected infant death (SUID), which includes SIDS, as well as suffocation, entrapment (between 2 objects, such as a mattress and wall), infection, ingestion (taking in something that blocks the airway), metabolic diseases, cardiac arrhythmias, and trauma.6

About 3500 US infants die suddenly and unexpectedly of causes under the SUID umbrella each year. Although many of the causes of death can’t be explained, most occur while infants are sleeping in unsafe sleeping environments.7

NEXT: Pediatricians' role in counseling

Pediatricians’ role in counseling

Community-based pediatricians play a big role in counseling parents and caregivers about safe sleep recommendations, according to Michal A Young, MD, associate professor and director, neonatal intensive care unit, Department of Pediatrics and Child Health, Howard University College of Medicine, Washington, DC. Young presented “Safe infant sleep (How do you counsel families who don’t use a crib?)“ at the October 2015 AAP National Conference and Exhibition in Washington, DC.

“[Pediatricians] see the parents, sometimes before delivery. But certainly they see them when they bring their babies in for the first post-delivery visit and have the opportunity to counsel them about safety in general,” Young says.

More: Obstructive sleep apnea in kids

Although many hospitals provide information about safe sleeping practices at discharge, Young says, parents might be overwhelmed with information and responsibility at that time and often need a refresher. “So it doesn’t hurt to go over that, just like [pediatricians] would for anticipatory guidance of any type. It may seem like a small thing, but it’s a big one,” she says.

What pediatricians need to know

Safe sleeping conversations between new parents and pediatricians should be free of assumptions, especially when it comes to mother-infant bed sharing.8

“You actually don’t know who doesn’t use a crib,” Young says. “When I talk about safe sleep, I assume nothing. I don’t know if they have a place to lay the baby, if they’re using a drawer, if they’re planning to sleep with the infant, or what their situation is. What I do know is that it is a natural reflex for moms to put babies in bed with them.”

The simple act of lying in bed with an infant doesn’t mean the parent intentionally plans to fall asleep, according to Young. Often, it’s a mistake. The parent falls asleep and wake up with the baby alongside on the bed, couch, or other surface.

NEXT: The impact of simple messages

Understanding why parents-most likely mothers-share beds with infants can help pediatricians focus their education efforts.8

More: Impact of technology on sleep patterns

One review suggests the most common reasons are: breastfeeding, comforting, getting more or better sleep, monitoring, bonding and attachment, environmental issues, crying, tradition, disagreeing with potential dangers, and maternal instinct.8

There are 3 maternal issues that can increase risk for SIDS from co-sleeping and bed sharing, according to Young. The risks of SIDS are greater among mothers who smoked cigarettes during pregnancy, as well as for babies exposed to environmental tobacco smoke once they’re home; mothers who have had inadequate prenatal care, because those mothers may have other medical issues or concerns; and among parents or caretakers who take anything that might alter their sleep, including medication for pain.

“Moms who smoked during pregnancy shouldn’t put babies in bed with them. A mother who is not breastfeeding shouldn’t put the baby in bed with her either. There is some controversy about placing the infant prone in the bed. I think it’s better to have [babies] on their backs, but there are different articles about that,” Young says.9

Simple messages go a long way

Young explains that the ABCs of safe sleep are easy for physicians to communicate to parents. The message that the AAP prefers, she says, is “Alone on my Back in a Crib.”

Among the barriers to parents’ getting the information, according to Young, is that pediatricians simply aren’t communicating about safe sleep. She says pediatricians can start the conversation by simply asking parents: “What are your plans for sleeping?”

“The pediatrician might not be talking about the plans for the baby’s sleeping, asking such questions as: Where is the baby in the room? Where will the baby go when you go home from the hospital?” Young says. “I think that’s the biggest issue, it’s the assumption, particularly in different populations, that people are not going to pay attention to what pediatricians are saying, so they don’t bother to talk at all.”

NEXT: Other tips from the CDC

There also are misconceptions among parents and caregivers, regardless of education, ethnicity, and more. Especially in Western society, Young says, parents might think it’s all right to set up a nursery down the hall, around the corner from their bedrooms.

“That really isn’t practical in those first couple of months. What is agreed on by most sciences is that proximity to the infant is the stimulus to breathing and regulating their systems appropriately,” Young says. “So, the baby should at least be in the room where the parents or the mother is sleeping. They don’t necessarily have to sleep on the same surface, but they should be in the same room. That makes it easy for mom to hear the baby if the infant cries or stirs, and the baby can hear and smell mom, so the baby will be less likely to be disturbed because of being placed so far away.”

Next: Avoiding overdiagnosis pitfalls

Other simple tips for safe sleeping, according to the CDC, include:10

· Use a firm sleep surface, such as a mattress in a safety-approved crib covered by a fitted sheet.

· Babies should be in the room with their parents, but not in their beds, on a couch, or on a chair alone.

· Loose bedding, pillows, and other soft objects should be kept away from the baby’s sleep area.

In addition, parents or caregivers should not smoke during pregnancy or around the baby after it is born. The CDC offers a free service for moms who want to quit, at 1-800-QUIT-NOW (1-800-784-8669) or Women.Smokefree.gov.10

Pediatricians can also help start the conversation by displaying posters about safe sleep recommendations in their practices, Young says.

“Sometimes it’s a difficult or uncomfortable thing for providers even to talk about. They should have a SIDS poster in the office, recommending sleep positions. It can trigger a conversation with parents. They may bring up the conversation if the physician or practitioner forgets to do it,” Young says.

Parents want this information and often heed physicians’ advice, according to studies.1,8 “It’s not really new evidence but it’s a finding that when you actually talk to parents, the parents would really like to know the things that are truly unsafe,” Young says.

However, that advice should come with some explanation. “If you just say, ‘Don’t sleep with the baby in the bed,’ [parents] might go sleep with the baby on the sofa, which is the highest risk place with an infant,” she says.

Pediatricians should explain why sleeping with a baby that’s less that’s aged younger than 3 months is risky, especially given that parents are often sleep deprived, Young says. Also, tell them why being on medications or substances that have altered their sleep patterns or their minds, such as alcohol or other sleeping agents, could cause them to fall asleep without meaning to.

Finally, don’t forget to talk about smoking, says Young. “I think people underestimate the issue of smoking and its impact on mothers and their infants,” she says. “[T]o make a real impact, we have to talk about safe sleep practices and safe sleep places, encourage mothers to breastfeed, and advise mothers not to smoke.”

REFERENCES

1. Smith LA, Colson ER, Rybin D, et al. Maternal assessment of physician qualification to give advice on AAP-recommended infant sleep practices related to SIDS. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(6):383-388.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sudden unexpected infant death and sudden infant death syndrome. Data and statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/sids/data.htm. Updated February 8, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2016.

3. National Institutes of Health. Safe to Sleep public education campaign. Progress in reducing SIDS. Available at: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sts/about/SIDS/Pages/progress.aspx. Reviewed October 29, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2016.

4. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, Moon RY. SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1030-1039.

5. National Institutes of Health. Safe to Sleep website. Available at:. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sts/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed April 15, 2016.

6. National Institutes of Health. Safe to Sleep. Common SIDS and SUID terms and definitions. Available at: https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sts/about/SIDS/Pages/common.aspx. Reviewed October 27, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2016.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sudden unexpected infant death and sudden infant death syndrome. About SUID and SIDS. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/sids/aboutsuidandsids.htm. Updated March 26, 2016. Accessed April 15, 2016.

8. Ward TC. Reasons for mother-infant bed-sharing: a systematic narrative synthesis of the literature and implications for future research. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19(3):675-690.

9. Unger B, Kemp JS, Wilkins D, et al. Racial disparity and modifiable risk factors among infants dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):e127-e131.

10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sudden unexpected infant death and sudden infant death syndrome. Parents and caregivers. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/sids/parents-caregivers.htm. Updated September 28, 2015. Accessed April 15, 2016.

Ms Hilton is a medical writer who has covered health and medicine for 25 years. She resides in Boca Raton, Florida. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.

Artificial intelligence improves congenital heart defect detection on prenatal ultrasounds

January 31st 2025AI-assisted software improves clinicians' detection of congenital heart defects in prenatal ultrasounds, enhancing accuracy, confidence, and speed, according to a study presented at SMFM's Annual Pregnancy Meeting.