Head lice: myths, facts, treatments

Back to school means saying hello to Pediculus humanus capitis-head lice. This special section reveals all you need to know about the creepy little critters and how you can help families rid their children of the infestation and the social stigma.

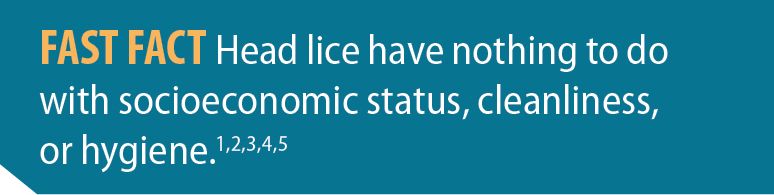

School is right around the corner, and so is the next influx of families with children who have contracted head lice-Pediculus humanus capitis (P humanus capitis). The critters pose no health hazard, are not a sign of poor hygiene, and, unlike body lice, do not spread disease.1,2 The greatest injuries that head lice cause seem to be the social stigma and anxiety they harbor.

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), infestations are common among children aged 3 to 12 years.1 Head lice occur regardless of socioeconomic status or hygienic living conditions and are common in many parts of the world, with an incidence in school children ranging from 2% to 52%. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that, in the United States, there are 6 million to 12 million infestations each year in this group.2 Interestingly, African Americans are less likely to play the unwilling host than are most other races, possibly because lice claws are less well adapted to grasping the shape and width of this type of hair shaft.

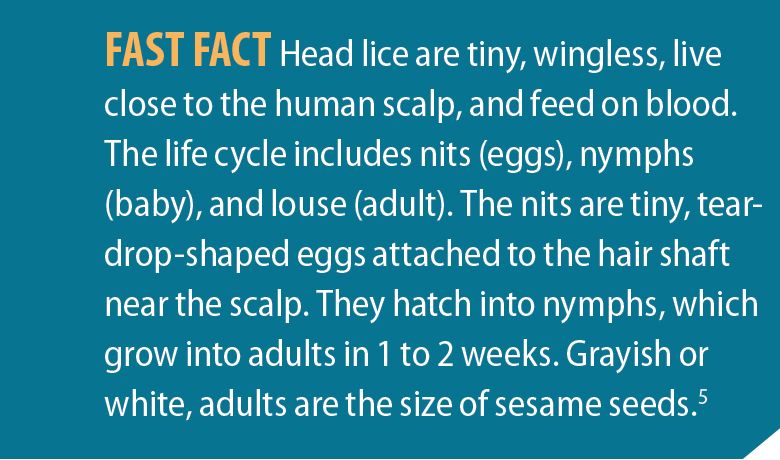

Head lice aren’t particularly mobile. They can’t fly or hop.2 They need help getting from 1 host to the next. Specifically, they need direct head-to-head contact-the type of contact common in schools, sleepovers, slumber parties, camps, and sports activities-that typically occurs among kids. Much less common is transmission via clothing, bedding, or sharing hairbrushes or combs. Because lice feet are adapted to holding onto human hair, they have a hard time getting (and keeping) a grip on plastic, metals, leather, and similar materials.

A sordid history

Societal panic and stigmatization of head lice are not new. Although head lice’s ancient lineage predates modern Homo sapiens by some 1.18 million years,6 once louse and man joined up, they stayed that way. Strands of hair from an early historic Wyoming mummy revealed evidence for the presence of P humanus capitis,7 and another study illustrates lice going to people’s heads about 170,000 years ago.8

Of nits and stigmas

The stigma took a little longer to catch on, but it’s tenacious. In the mid-1700s, sentiments expressed by Robert Burns-that lice were disgusting, the well-to-do should be protected from them, and the poor deserved them-were pervasive.9 In the mid-1800s, lice infestations netted men 6 lashes with a cat-o’-nine-tails.10

Contemporary estimates are that 6 million to 12 million cases of head lice occur each year in the United States in children aged 3 to 12 years.11

In an effort to curtail the spread of the parasites, Canada, Australia, and the United States implemented “no-nit” policies that entailed the immediate dismissal of all children with head lice, eggs, and/or nits from schools, camps, or child care settings.13 However, because only a small number of children with nits on their hair are also infested with living lice, this policy did little to stem the spread of the parasite, but much to spread fear and confusion. It also made a serious annual dent in the economy, costing $4 billion to $8 billion in missed workdays for parents needing to stay home with their children.

Assessing the damage

These policies-established years ago and based on fear and misinformation rather than scientific evidence-are formulated on a parasite that transmits no diseases to humans and that has nothing to do with poor hygiene or a sanitary home environment.2,11,18 Close, head-to-head contact is the primary method of transmission.2 It’s easy to see how fear, anxiety, and psychological trauma can be the worst part of a head lice diagnosis.

Researchers have found that parents and caregivers of infected children suffer the consequences as well, often feeling ostracized, losing self-integrity, struggling with persistence of infection, and having difficulty managing strain.19 Another study noted the negative social effects of the head lice stigma as more problematic than the infection itself, including quarantine, overtreatment, and potentially negative psychological impact.20 Innocuous and unhealthy home remedies, such as the use of flammables or pesticides, were common, reflecting the confusion of parents who blamed head lice as the cause of various health problems not related to the insect.21

Treatments: archaic and contemporary

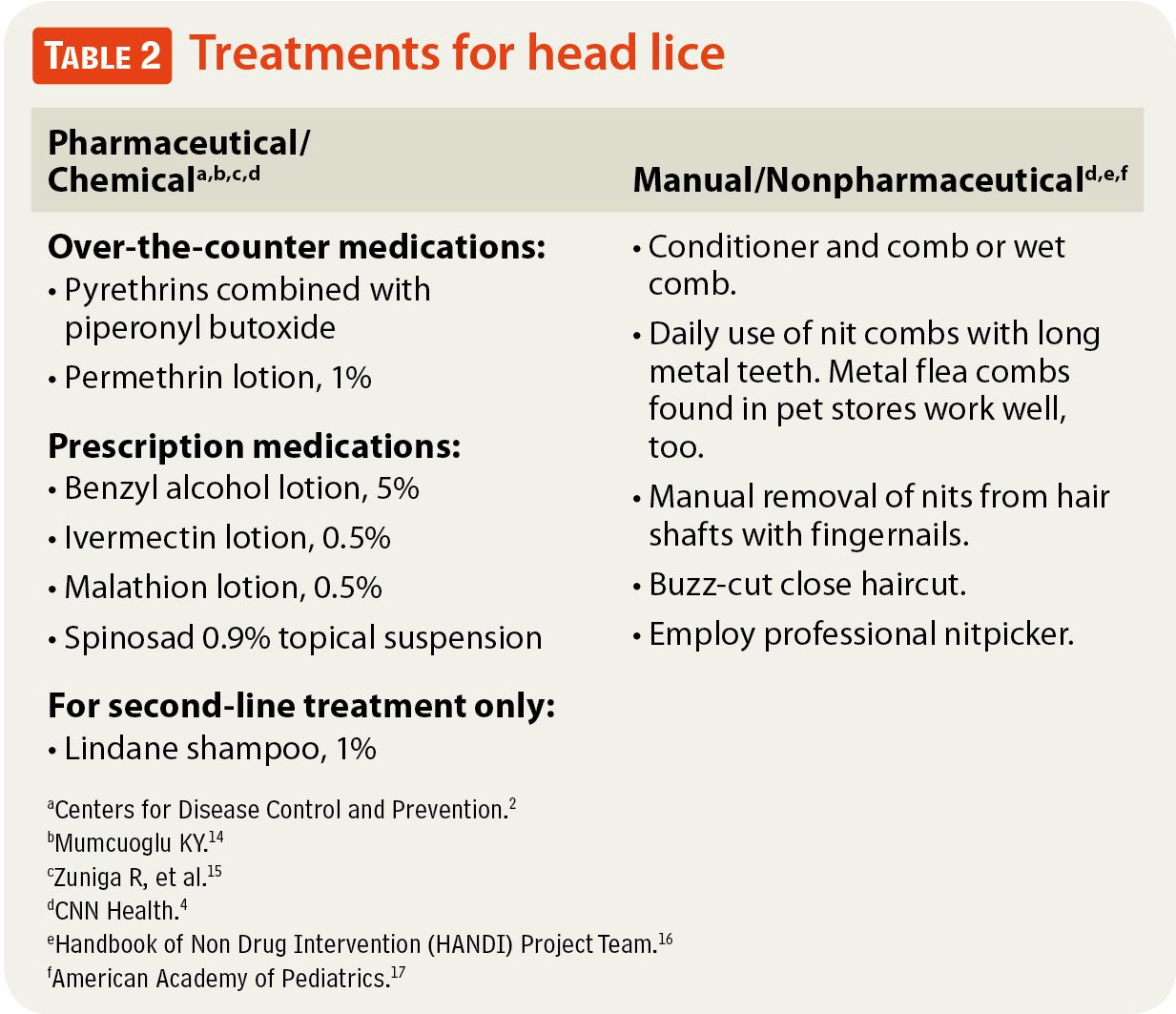

Treatment for head lice ranges from the archaic-manual removal and home remedies-to the pharmaceutical and mechanical.3,14,16,22 Before the advent of modern applications, people improvised with what was available, from date flour in the 16th century BC to later use of quicksilver, cresol, naphthalene, sulphur, mercury, kerosene, oil, and vinegar.14

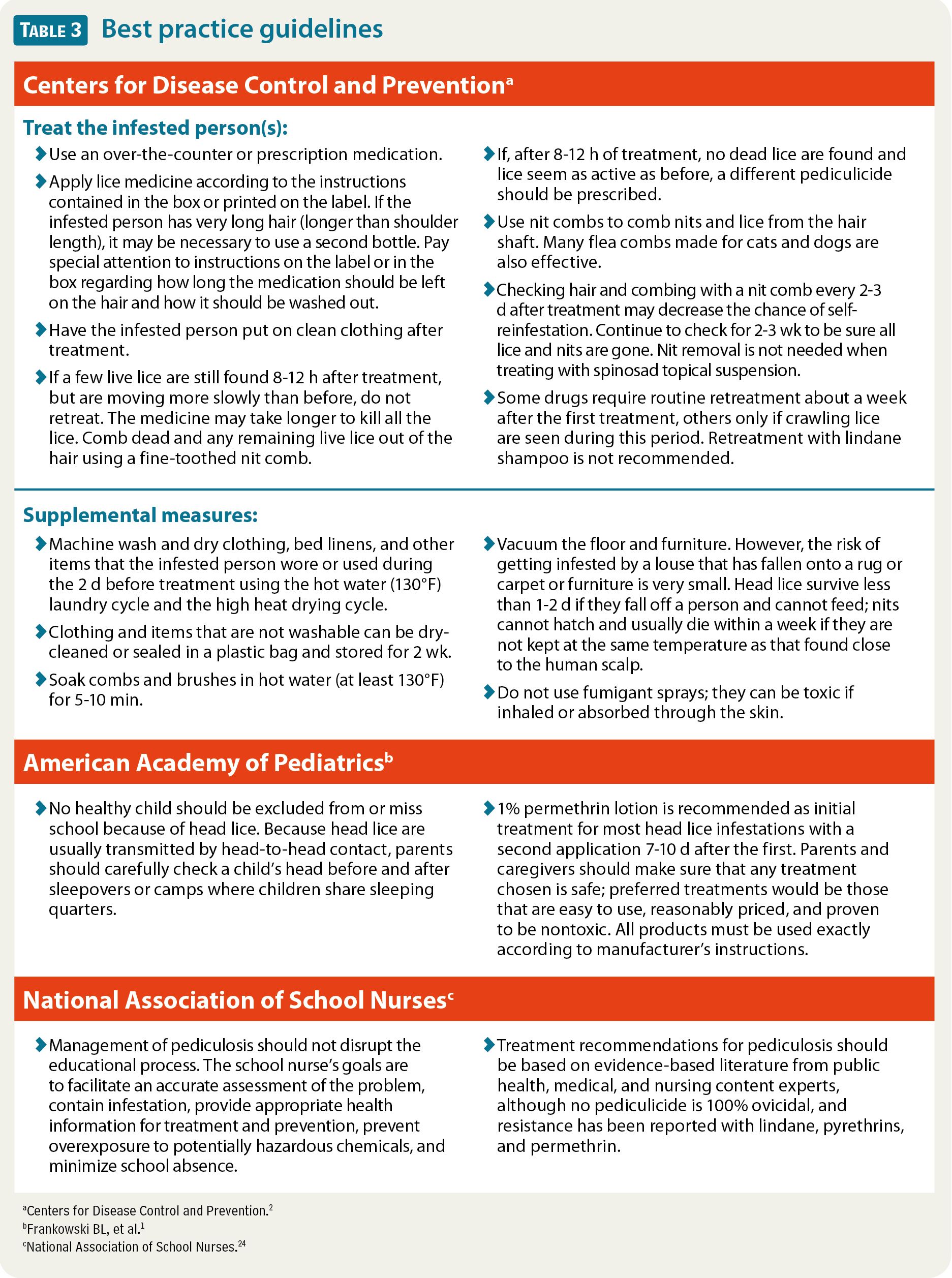

While effective, insecticides have been met with evolution of pesticide-resistant strains of parasites, which has mandated strategic combinations and sequencing of product application.3,14 Topical permethrin remains the first-line treatment, although permethrin-resistant strains can complicate its efficacy.15 If 2 applications of permethrin are ineffective, topical application of malathion or ivermectin and even the off-label use of oral ivermectin may be indicated.

EDITOR'S NOTE: As an addendum to "Head lice: myths, facts, treatments" (Contemporary Pediatrics, August 2013), the latest edition of AAP's Red Book lists malathion, benzyl alcohol, and spinosad suspension as effective topical treatments for head lice after permethrin failure.

Amerian Academy of Pediatrics. Pediculosis capitis (head lice). In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Acadeny of Pediatrics; 2012:543-545.

This tendency of the little parasites to evolve drug resistance makes their effective manual removal, plus education of parents on lice biology and control, all the more important for managing infestation and preventing reinfestation.16,22

Myths and facts

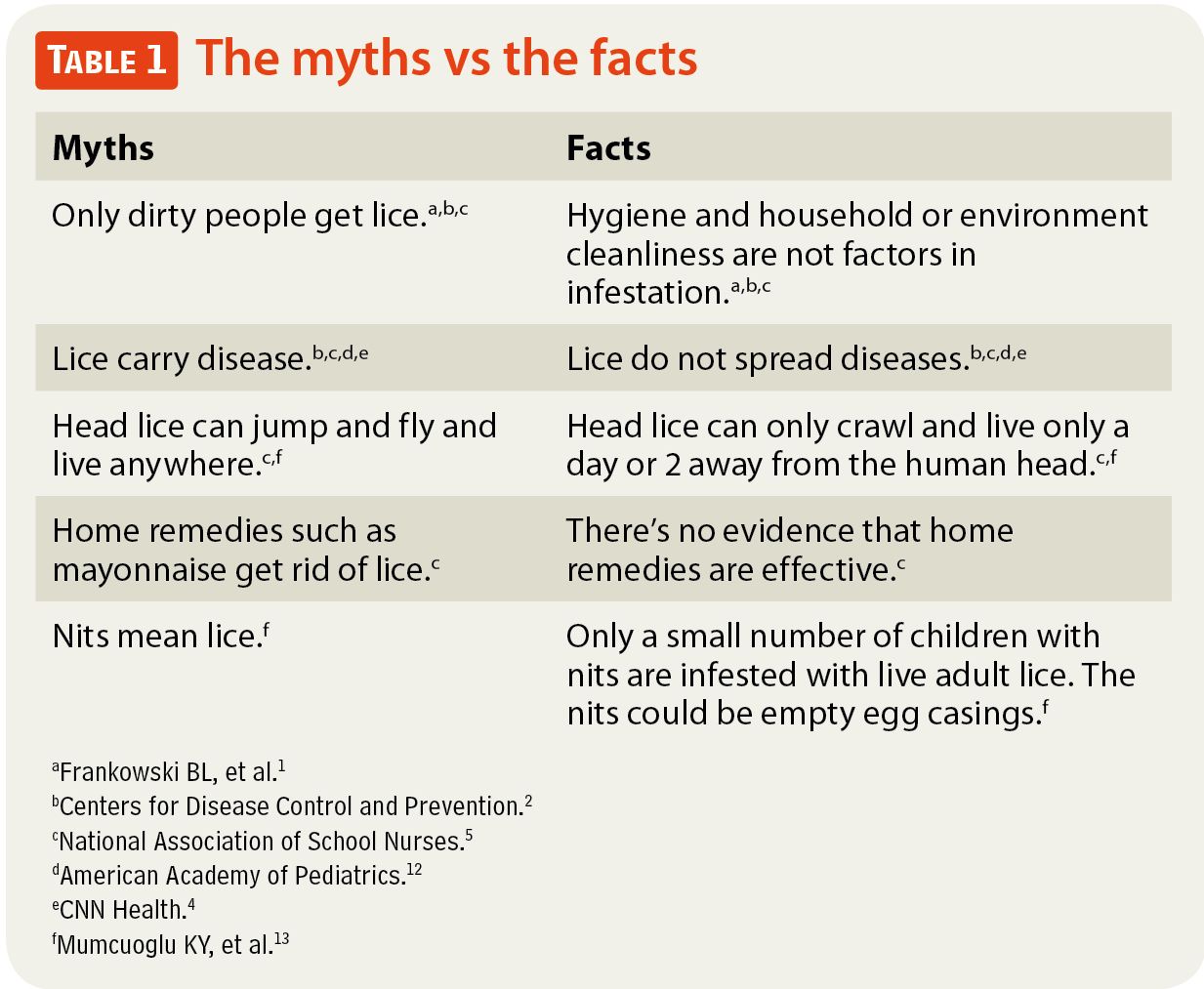

For all the stigma, fear, and psychological trauma they cause, head lice are actually pretty delicate, high-maintenance critters. A quick look at the myths and facts can set the record straight, and shift the power differential away from the parasites.

Head lice favor all socioeconomic groups and make themselves at home regardless of the health, hygiene, or cleanliness of their unwilling hosts. They don’t spread disease. Really, all they do is create a disproportionate brouhaha, and their stigma is far worse than their bite. One of the worst effects of a head lice infestation is the psychological trauma that goes along with the diagnosis.

Knowledge is power, and this is certainly true where P humanus capitis is concerned. Educating parents and children about head lice myths and facts is key to demystifying the stigma. If pediatricians and school officials react calmly, parents can focus on treatment without the drama.1

REFERENCES

1. Frankowski BL, Bocchini JA Jr; Council on School Health and Committee on Infectious Diseases. Head lice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):392-403.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Parasites–Lice–Head Lice. Frequently asked questions. CDC Web site. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lice/head/gen_info/faqs.html. Updated November 10, 2010. Accessed July 18, 2013.

3. Eisenhower C, Farrington EA. Advancements in the treatment of head lice in pediatrics. J Pediatr Health Care. 2012;26(6);451-461.

4. CNN Health. Quick guide to head lice.10 things to know about head lice. CNN Web site. http://inhealth.cnn.com/quick-guide-to-head-lice/10-things-to-know-about-head-lice/. Last reviewed June 7, 2012. Accessed July 18, 2013.

5. National Association of School Nurses (NASN). Lice lessons. NASN Web site. www.nasn.org/toolsresources/headlicepediculosiscapitis/licelessons. Updated March 2013. Accessed July 18, 2013.

6. Reed DL, Smith VS, Hammond SL, Rogers AR, Clayton DH. Genetic analysis of lice supports direct contact between modern and archaic humans. PLoS Biol, 2004;2(11):e340.

7. Gill GW, Owsley DW. Electron microscopy of parasite remains on the Pitchfork mummy and possible social implications. Plains Anthropol. 1985;30:45-50.

8. Toups MA, Kitchen A, Light JE, Reed DL. Origin of clothing lice indicates early clothing use by anatomically modern humans in Africa. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(10):29-32.

9. Ibarra J, Hall DM. Head lice in schoolchildren. Arch Dis Child, 1996;75(6):471-473.

10. Winston A. The Brutal Whip. American History Illustrated, February 1972. Gettysburg, PA: National Historical Society; 1972;10-14.

11. Sciscione P, Krause-Parello CA. No-nit policies in schools: time for change. J Sch Nurs. 2007;23(1):13-20.

12. American Academy of Pediatrics. Health issues. Signs of lice. HealthyChildren.org Web site. www.healthychildren.org/english/health-issues/conditions/from-insects-animals/pages/signs-of-lice.aspx. Updated May 11, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2013.

13. Mumcuoglu KY, Meinking TA, Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Head louse infestations: the “no nit” policy and its consequences. Int J Dermatol, 2006;45(8):891-896.

14. Mumcuoglu KY. Control of human lice (Anoplura: Pediculidae) infestations: past and present. Am Entomol. 1995;42(3):175-178.

15. Zuniga R, Nguyen T. Skin conditions: emerging drug-resistant skin infections and infestations. FP Essent. 2013;407:17-23.

16. Handbook of Non Drug Intervention (HANDI) Project Team. Wet combing for the eradication of head lice. Aust Fam Physician. 2013;42(3):129-130.

17. American Academy of Pediatrics. Health issues. Signs of lice. HealthyChildren.org Web site. www.healthychildren.org/english/health-issues/conditions/from-insects-animals/pages/signs-of-lice.aspx. Updated May 11, 2013. Accessed July 18, 2013.

18. California Department of Public Health (CDPH). Guidance on head lice prevention and control for school districts and child care facilities. CDPH Web site, http://cdph.ca.gov/HealthInfo/discond/Documents/2012SchoolGuidanceonHeadLice.pdf. Published May 2012. Reposted September 2012. Accessed July 18, 2013.

19. Gordon SC. Shared vulnerability: a theory of caring for children with persistent head lice. J Sch Nurs, 2007;23(5):283-292.

20. Parison JC, Speare R, Canyon DV. Head lice: the feelings people have. Intl J Dermatol. 2013;52(2):169-171.

21. Silva L, Alencar Rde A, Madeira NG. Survey assessment of parental perceptions regarding head lice. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47(3):249-255.

22. Gallardo A, Toloza A, Vassena C, Picollo MI, Mougabure-Cueto G. Comparative efficacy of commercial combs in removing head lice (Pediculus humanus capitis) (Phthiraptera: Pediculidae). Parasitol Res. 2013;112(3):1363-1366.

23. California Department of Public Health. A parent’s guide to head lice. www.cdph.ca.gov/healthinfo/discond/documents/2012headliceeng.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed July 28, 2013.

24. National Association of School Nurses (NASN). Pediculosis management in the school setting. Position statement. NASN Web site. http://www.nasn.org/PolicyAdvocacy/PositionPapersandReports/NASNPositionStatementsFullView/tabid/462/smid/824/ArticleID/40/Default.aspx. Published November 1999. Revised July 2004; January 2011. Accessed July 18, 2013.

Subscribe to Contemporary Pediatrics to get monthly clinical advice for today's pediatrician.