Incontinentia Pigmenti

IP is a rare X-linked dominant disorder. About 700 to 1000 cases have been reported worldwide (about 1 in 50,000 live births); white infants are most commonly affected. In a review of 653 patients, more than half had a family history of the condition.1 Our patient's mother was also affected. IP usually appears within the first 2 weeks of life. The severity and expression of the disorder are highly variable, even among patients within the same family.1,3 The condition is characterized by anomalies of the organs and tissues derived from the ectoderm and mesoderm and may affect the skin, hair, nails, teeth, eyes, and CNS1,2:

FigureA 9-month-old African American girl presented with whorls of hyperpigmentation in a swirled pattern on the extremities and trunk. This condition began at birth as a linear rash of vesicles and pustules: in a female infant, this pattern is diagnostic of incontinentia pigmenti (IP)-also known as Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome. The characteristic hyperpigmentation is the result of excessive deposits of melanin in the superficial dermis.

1,2

IP is a rare X-linked dominant disorder. About 700 to 1000 cases have been reported worldwide (about 1 in 50,000 live births); white infants are most commonly affected. In a review of 653 patients, more than half had a family history of the condition.1 Our patient's mother was also affected. IP usually appears within the first 2 weeks of life. The severity and expression of the disorder are highly variable, even among patients within the same family.1,3 The condition is characterized by anomalies of the organs and tissues derived from the ectoderm and mesoderm and may affect the skin, hair, nails, teeth, eyes, and CNS1,2:

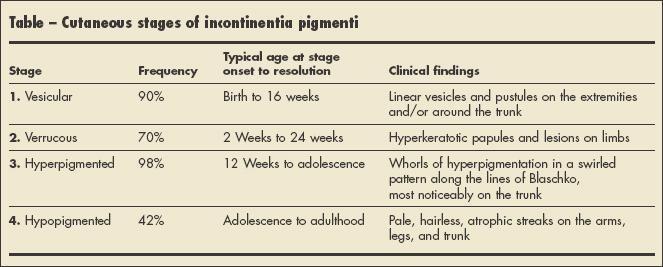

- Skin. The 4 stages of IP are listed chronologically in the Table; these stages can overlap and not all stages necessarily occur.1-4

- Hair. Half of patients with IP have minor hair abnormalities (such as wiry or coarse hair) and 38% have alopecia, especially at the vertex.1,5

- Nails. Nail dystrophy occurs in up to 40% of patients with IP and ranges from mild ridging of the nails to onychogryposis. 1,5 Dystrophic nails are temporary and regress with age.4

- Teeth. About 70% to 95% of affected patients have dental anomalies, including delayed dentition, partial anodontia, and pegged or conical teeth.3,5

- Eyes. Retinal cells develop abnormally in 40% of patients with IP. In infants and children, this increases the risk of retinal detachment. Other associated anomalies include optic atrophy, cataract, and microphthalmos.1,4

- CNS. About 30% of patients with IP present with CNS anomalies, most commonly seizures.2,4 Learning disabilities, developmental delay, and mental retardation are rare associations.5

Transmission of IP is caused by mutations in the nuclear factor-kB essential modulator (NEMO) gene located at chromosome Xq28.1,3 This gene controls inflammatory responses and cellular apoptosis and is also found in anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immune deficiency.1 A deletion of exons 1 to 4 is identified in 85% of patients.1,3 IP is almost always lethal for the hemizygous male fetus in the first trimester; therefore, 97% of patients with this disorder are female.2,3 Females with IP mutations survive because of heterozygosity at the NEMO locus and skewed X inactivation, where the mutant X chromosome is preferentially inactivated.5 Males with IP usually have Klinefelter syndrome (47,XXY), in which the XXY genotype allows survival.1,2 Interestingly, the severity of IP is not related to the type of mutation.6

Table

The diagnosis of IP is based on the clinical history and examination. Skin biopsies can be helpful in unusual presentations; each stage is characterized by certain histopathological findings.5 Histological features that reflect keratinocyte apoptosis can help clarify an IP diagnosis and may be included as a major criterion for diagnosing IP.6 Genetic counseling should involve both the patient and relatives. When cases are in doubt, DNA studies can help ascertain or rule out the diagnosis.

Patients with IP in the early stages may require standard wound care to decrease the likelihood of secondary infections associated with blister formation, especially with the emergence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.4,5 The severity and outcome of IP is directly related to ocular and neurological impairment. A complete neurological examination and regular visits to an ophthalmologist and dentist are recommended to achieve optimal outcomes.

References:

- Berlin AL, Paller AS, Chan LS. Incontinentia pigmenti: a review and update on the molecular basis of pathophysiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:169-190.

- Faloyin M, Levitt J, Bercowitz E, et al. All that is vesicular is not herpes: incontinentia pigmenti masquerading as herpes simplex virus in a newborn. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e270-e272.

- Paller AS, Mancini AJ, eds. Hurwitz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2006: 280-283.

- Zitelli B, Holly D, eds. Atlas of Pediatric Physical Diagnosis. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:298-300.

- Landy SJ, Donnai D. Incontinentia pigmenti (Bloch-Sulzberger syndrome). J Med Genet. 1993;30:53-59.

- Hadj-Rabia S, Froidevaux D, Bodak N, et al. Clinical study of 40 cases of incontinentia pigmenti. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139:1163-1170.

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.