ITP: How much treatment is enough?

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is easy to recognize and generally not serious. Yet specialists differ greatly in their approach to diagnosis and treatment. Review the rationales of the opposing camps, then make up your own mind on which makes better sense.

ITP: How much treatment is enough?

By George R. Buchanan, MD

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura is easy to recognize and generally not serious. Yet specialists differ greatly in their approach to diagnosis and treatment. Review the rationales of the opposing camps, then make up your own mind on which makes better sense.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reviewing this article the physician should be able to:

- Recognize the presenting manifestations of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

- Understand that only a limited diagnostic evaluation is required in the typical patient.

- State the pros and cons of various treatment strategies for acute ITP.

- Know the differential diagnosis of chronic thrombocytopenia during childhood.

- Describe treatment strategies for children with chronic ITP, including the merits and potential disadvantages of splenectomy.

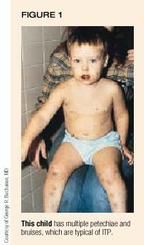

Every pediatrician has encountered the following situation: A generally healthy child, usually between 2 and 8 years of age, suddenly develops multiple petechiae, bruises, and maybe a minor nosebleed or two, several weeks after being diagnosed with a nonspecific viral infection. The distraught parents, worried about the possibility of leukemia or life-threatening bleeding, rush the child to the office. The physical examination is unremarkable except for the hemorrhagic manifestations, and a complete blood count shows marked thrombocytopenia but normal hemoglobin and leukocyte values.

This child, like the boy pictured on the right, has idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), one of the most common pediatric hematologic disorders. ITP generally is not serious and is easy to diagnose. Yet ITP specialists differ greatly on how to verify the diagnosis, on how aggressively to treat it, and on whether the general pediatrician can care for most children with ITP. To decide which approach to take when you encounter a child with ITP, you need a good grasp of the disorder's natural history, the available treatments, and the arguments of physicians who stand on opposing sides of several diagnostic and management controversies.

Features of ITP

ITP incidence is unknown because many mild cases go unnoticed, but annual incidence of symptomatic ITP probably is about four or five cases per 100,000 children. ITP affects patients of all ages, even infants,1 but it is most prevalent during early to mid-childhood. Although passive antiplatelet antibody from the mother may cause immune-mediated thrombocytopenia in the neonate, de novo ITP rarely is seen before 3 or 4 months of age. The condition affects males and females equally and occurs in all ethnic groups, although mild cases are more likely to be missed in children with dark skin.

In a sense, a child with ITP is allergic to his or her own platelets. Put more technically, ITP is an immune-mediated disorder characterized by production of antiplatelet antibodies or immune complexes. These antibodies bind to glycoprotein antigens on the platelet surface, resulting in the rapid destruction of the platelet by macrophages in the spleen and other organs. Platelet production in the bone marrow also may be impaired.

Making the diagnosis

The relationship between the previously existing or concomitant viral infection and development of ITP is often ill defined. Many pathogens, including the varicella zoster, measles, and Epstein-Barr viruses, and mild bacterial infections have been reported to trigger ITP. The association between HIV infection and immune thrombocytopenia is well known, so this diagnosis should be considered in patients who are at risk for or have other clinical features suggestive of HIV infection. Most prior infections, however, are mild and nonspecific.

ITP generally occurs in previously healthy children although, somewhat paradoxically, patients with congenital immunodeficiency are particularly prone to develop ITP and other immune-mediated hematologic disorders. The family history is usually negative for hematologic conditions.

Physical examination. On physical examination, the child with ITP appears healthy (Table 1). Petechiae are usually present, often in crops around pressure points and on the neck and upper trunk. Petechiae are not numerous when the platelet count is between 20,000 and 50,000/µL but are invariably seen with lower platelet counts. Some children with ITP whose platelet counts are below 10,000/µL have epistaxis, gum bleeding, and blood-filled blisters in the mouth. Life-threatening gastrointestinal or intracranial hemorrhage fortunately is rare.

Children with ITP are not pale (unless they have lost appreciable quantities of blood), nor do they have significant lymphadenopathy or hepatosplenomegaly. A markedly enlarged spleen virtually excludes an ITP diagnosis and should make you suspect leukemia or other conditions.

Laboratory evaluation. Children believed to have ITP do not need an extensive laboratory assessment.2 Generally, a complete blood count is the only test required. The hemoglobin is normal (or slightly reduced if the child has had external bleeding) as is the white blood count. The bleeding time test is unnecessary as the time almost surely will be prolonged.

Many physicians order a prothrombin time (PT) and partial thromboplastin time (PTT) to rule out disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), the only clinical condition or syndrome that results in a low platelet count and prolonged PT and PTT. These tests, too, typically are not required, however, because children with DIC invariably are ill with an underlying disorder, whereas children with ITP clearly are not.

Antiplatelet antibody assays lack sensitivity and specificity and have not proven useful clinically. Studies to investigate a specific viral etiology (HIV antibody test, monospot, or Epstein-Barr virus serologies) are helpful in selected cases. An investigation for an underlying immunologic disorder generally is not called for in the young child with acute ITP, although teenagers and children with chronic ITP should be screened.

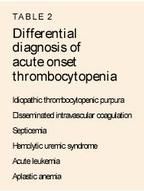

Differential diagnosis. Table 2 lists the most common causes of acute thrombocytopenia. Diagnosing ITP tends to be straightforward because, like DIC, most other entities in the differential diagnosis occur in children who are very ill, have findings not seen in ITP on physical examination, or have an underlying systemic disorder.

A matter of approach

Despite the ease with which childhood ITP can be identified, its diagnosis and treatment have inspired several controversies during the past 30 years. These disagreements probably never will be resolved by scientific studies, in part because they reflect philosophic differences in practice style among physicians who treat children with ITP (Table 3). Some physicians think the child with ITP always should be referred to a pediatric hematologist/ oncologist. They favor extensive diagnostic testing and aggressive therapy so as not to miss possible alternative diagnoses or "take chances" that life-threatening hemorrhage may develop. These doctors can be termed therapeutic activists or "interventionists." Other physicians, including me, take a less aggressive, minimalist, or "noninterventionist" approach and think a general pediatrician can care for most children with ITP. (During lively arguments with their interventionist colleagues, these physicians are sometimes called therapeutic nihilists.) Depending on the philosophic camp to which they belong, physicians vary in how they approach several key issues.

Bone marrow aspiration. One issue is whether a bone marrow aspiration is needed to make sure that the child with presumed ITP does not have acute leukemia or aplastic anemia, the most feared entities in the differential diagnosis of ITP. In both leukemia and aplastic anemia, thrombocytopenia is caused by decreased platelet production. This occurs when leukemic cells displace megakaryocytes from the marrow, reducing the quantity of megakaryocytes, or when the marrow is injured. In ITP, on the other hand, thrombocytopenia results from increased platelet destruction; consequently, children with this condition have normal bone marrows with abundant megakaryocytes.

Aside from thrombocytopenia, the blood count of children with ITP is normal. But in children with leukemia or aplastic anemia, the blood count would be expected to show reduced hemoglobin and granulocytes resulting from a packed or empty marrow. Consequently, results of the blood count differentiate the child with ITP from the child who might have aplastic anemia or leukemia; a bone marrow aspirate is not needed.

Nonetheless, many interventionist practitioners request or perform a bone marrow aspiration in virtually every child with suspected ITP to "rule out" leukemia. These physicians often affirm that parents insist on this approach because of their fear of leukemia. Further, they claim to have seen children with leukemia who present only with thrombocytopenia, even though such cases are not well documented in the literature.3 One study showed that none of 2,239 patients newly diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia exhibited isolated thrombocytopeniathat is, a platelet count of less than 50,000/µL but an otherwise normal blood count and physical examination.4

Certainly no one would question performing a bone marrow aspiration when the child has bone pain, splenomegaly, anemia not explained by acute blood loss, an increased erythrocyte mean cell volume or mean corpuscular volume (which suggests marrow failure), or a worrisomely abnormal differential white blood count. However, when the child has a straightforward case of acute ITP, a painful and relatively costly bone marrow aspiration is not required.5 In my experience, parents of a patient newly diagnosed with ITP never insist that their child have the procedure after I explain that the diagnosis is virtually certain and assure them that their child will be closely followed.

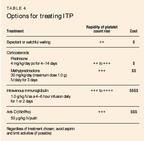

Management. Noninterventionists treat ITP with watchful waiting, while interventionists rely on pharmacotherapy (Table 4). Most children with ITP recover within weeks to months (sometimes even days) without requiring hospitalization, pharmacologic therapy, frequent blood count monitoring, or ongoing management by a hematologist. Typically, the petechiae, bruising, and mucosal hemorrhage that initially are present diminish after five to seven days. Within several weeks the platelet count usually begins to rise, although it fluctuates somewhat. Once the platelet count returns to normal (more than 150,000/µL), only rarely does it decline to a level where the child is again symptomatic, unless corticosteroids or intravenous gamma globulin (IV IgG) or anti-D immunoglobulin have been administered, as discussed below.

The noninterventionist reassures the parents and follows the child in the office once or twice each week with a brief physical examination and CBC, including a platelet count. Hospitalization is usually unnecessary except when the diagnosis is uncertain or mucosal bleeding occurs. Aspirin and aspirin-containing drugs should be avoided, as they generally already are in pediatric patients.

Limiting the child's activities is advisable, although this is often impossible when the patient is an active 2- or 3-year-old who feels well. Children should be kept home from school during the initial few days of the illness when new clinical bleeding is apparent and should refrain from physical education until the platelet count has begun to rise. They should not engage in competitive contact sports that are associated with head injuries.

Pharmacologic approaches

The process of spontaneous recovery from childhood ITP can be accelerated by administering corticosteroids (prednisone or methylprednisolone), high doses of IV IgG, or anti-D immunoglobulin. Physicians with an interventionist approach recommend drug treatment for virtually all children with ITP. Other physicians reserve these forms of therapy for selected patients with substantial mucosal hemorrhage or possible internal bleeding, and for those in whom trauma or a surgical procedure necessitates an immediate rise in the platelet count.

Corticosteroids. For years some physicians have advised oral prednisone therapy for children with ITP. Prednisone blocks the reticuloendothelial system's destruction of antibody-coated platelets and increases platelet production.6 Moreover, prednisone and its derivatives may have a direct capillary stabilizing effect, reducing bleeding signs and symptoms while not necessarily affecting the platelet count. The usual dose, 2 mg/kg/day for one to three weeks, may cause the platelet count to rise somewhat faster than it would otherwise. Several randomized studies have offered conflicting results regarding steroid's beneficial effect.79

Some practitioners use higher doses of oral prednisone, such as 4 mg/kg/day, or very large doses of intravenous methylprednisolone (usually 30 mg/kg for three consecutive days).10 Long-term corticosteroid therapy is contraindicated, as is "chasing" the platelet count with intermittent courses of steroid therapythat is, reinitiating prednisone when the platelet count declines after an apparent rise following the initial course of treatment.8

IV IgG. Early in the 1980s it was shown that high doses of IV IgG often caused the platelet count to rise promptly in children with ITP.11 Reticuloendothelial blockade is the probable mechanism. The most commonly employed IV IgG dosage schedule at present is 1 g/kg daily for one to two days.12

In many children with ITP, platelet counts rise above 30,000/µL within a day or two of IV IgG treatment. If such an immediate rise is the primary aim of treatment, then IV IgG therapy should be successful in most patients. Several studies show that IV IgG therapy more often results in a rapid incremental increase of platelets than treatment with prednisone or no treatment.8,9

Although IV IgG has been the most popular treatment overall for children with newly diagnosed ITP,13 a worldwide shortage of IV IgG has developed during the past several years. Difficulties in obtaining IV IgG preparations have resulted in employment of alternative treatment approaches.14

Anti-D immunoglobulin (Win Rho). Anti-D or anti-Rh immunoglobulin is a relatively new treatment modality with a more selective mechanism of action than IV IgG. Licensed in the United States several years ago, anti-D is less costly and easier to administer than IV IgG. It has been shown to be as effective or nearly as effective as IV IgG in rapidly increasing the platelet count in children with newly diagnosed ITP.15,16 It is administered as an intravenous push injection. It works in an interesting fashion. The anti-D coats the patient's D-positive erythrocytes, causing them to be ingested by macrophages in the spleen. The macrophages, having "eaten" the antibody-coated erythrocytes for "lunch," are satiated and therefore fail to ingest the antibody-coated platelets; the platelet count subsequently increases. Not surprisingly anti-D is useful only for Rh(D)-positive patients.

Disadvantages of drugs. Although a short course of oral prednisone is usually neither costly nor risky, it often does not increase the platelet count, and virtually all children who receive prednisone have at least modest toxicity, characterized by moodiness, irritability, insomnia, and weight gain. IV IgG therapy also has problems. First, it is extremely expensive; a single course of 1 to 2 g/kg costs between $2,000 and $5,000, not including additional clinic or inpatient charges, physicians' fees, the costs of IV tubing, and other miscellaneous expenses. IV IgG therapy frequently causes nausea, vomiting, and headaches.

A splitting headache that develops a few hours after a child with a very low platelet count receives IV IgG occasionally prompts an emergency room visit and emergency CT scan of the brain (costing another $1,200) to convince the extremely worried parents and treating physicians that an intracranial hemorrhage has not occurred.17 IV IgG may also cause aseptic meningitis, and in the past contaminated lots were responsible for dozens of cases of hepatitis C infection. The benefit of IV IgG a rise in platelet count in some patientstherefore may not outweigh its risks and inconveniences. Also, patients with severe hemorrhage often fail to respond to IV IgG.18 Anti-D also has its disadvantages. Although virally inactivated, it is still a blood product. So it may cause febrile reactions and has theoretical risks of infectious disease transmission. It also causes a low-grade hemolytic anemia. Finally, its cost is "low" only relative to IV IgG. A single dose costs $1,000 or more.

Even the most ardent interventionists will admit that neither corticosteroids, IV IgG, nor anti-D impact upon the natural history of ITthat is, they do not "prevent" the acute form of the disease from evolving into chronic thrombocytopenia.

Other treatments

On rare occasions, especially in older children and teenagers, acute ITP may be associated with severe bleeding that is unresponsive to steroids and IV IgG, prompting consideration of splenectomy and some of the other therapeutic measures usually reserved for children with chronic ITP. Platelet transfusions are indicated only when life-threatening bleeding occurs. They are otherwise ineffective because of the platelets' brief life span.

Problem bleeding

A few children with acute ITP develop severe or persistent mucous membrane hemorrhage, especially epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding. These children may need packed red blood cell transfusions and are candidates for steroid, anti-D, or IV IgG therapy.

The most feared complication of ITP, intracranial hemorrhage, fortunately is rare. Although it was once believed to occur in 1% or more of patients with ITP, more recent reviews have suggested a 0.1% to 0.5% incidence. The best population-based data come from the United Kingdom, where it has been estimated that 1 in 800 children with ITP develop intracranial hemorrhage.19

Although central nervous system hemorrhage is extremely rare, it can be devastating. It most commonly follows an episode of head trauma or inadvertent aspirin use, when the platelet count is less than 20,000/µL and when the child has profuse bleeding in other sites as well. It is possible that occult arteriovenous malformations or vasculitis is an additional risk factor in some cases.1820 When intracranial hemorrhage occurs, all of the aforementioned treatments, including platelet transfusion, should be employed, as well as neurosurgical evacuation of the clot when feasible. With aggressive therapy, at least half of children having intracranial hemorrhage may survive without sequelae.21 In 24 years of practicing pediatric hematology, I have encountered intracranial hemorrhage in only one child with ITP under 10 years of age and just four cases altogether.

Chronic ITP

The 20% of children with ITP who do not fully recover within six months are classified as having chronic ITP. Chronic ITP has two distinct clinical patterns. In one, the child has been known to have ITP for the previous six months and has been followed with the hope that the disease would resolve spontaneously. Alternatively, the child with chronic ITP may have a prolonged and insidious history of petechiae and easy bruising before mild to moderate thrombocytopenia (platelet count 20,000 to 80,000/µL) is identified. Children with chronic disease are more likely than those with acute ITP to have a bona fide autoimmune disorder. Approximately one-third of such patients exhibit other clinical and laboratory phenomena consistent with autoimmunity, such as a family history of collagen-vascular disease, or have other abnormalities such as those described below.

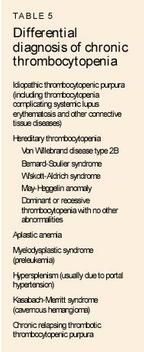

All chronic thrombocytopenia is not chronic ITP, as shown in the differential diagnosis of the child who shows a persistently low platelet count (Table 5). Practitioners sometimes confuse aplastic anemia or a myelodysplastic syndrome (preleukemia) with chronic ITP. When early marrow failure or marrow injury characteristic of myelodysplastic syndrome or aplastic anemia shows itself primarily as thrombocytopenia, the child almost always has borderline or mild anemia, erythrocyte macrocytosis, or subtle changes in the leukocyte count, unlike the child with chronic ITP.22 Some of the other entities in the differential diagnosis (giant hemangioma and portal hypertension, for example) can be easily distinguished from chronic ITP on physical examination.

However, hereditary thrombocytopeniaincluding type 2B von Willebrand diseasemay mimic chronic ITP in numerous respects. Children with one of these disorders are generally well, have normal blood counts except for thrombocytopenia, and have normal- appearing bone marrows. Yet unlike children with ITP, their platelets may be very small (as in the Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome) or extremely large. Early onset of hemorrhage is seen and sometimes a positive family history. Children with familial thrombocytopenia characteristically do not respond to corticosteroids, gamma globulin, and splenectomy.

Diagnostic and treatment considerations for chronic ITP are similar to those for the acute form of the disease. The patient with chronic ITP who has any abnormalities, even slight, in the erythrocytes or leukocytes should undergo a bone marrow aspiration. Screening for an underlying immunologic disorder generally includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) determination, direct antiglobulin (Coombs') test, and measurement of quantitative immunoglobulins. Up to 20% of children with chronic ITP have a positive ANA. These patients should be further evaluated for systemic lupus erythematosus (that is, undergo antiDNA measurement, complement studies, and the like), although only a few will have the disorder. A positive Coombs' test is of concern, as it may be the harbinger of an autoimmune hemolytic anemia (which in combination with ITP has been termed Evans syndrome). Many children with chronic ITP have mildly reduced levels of one or more serum immunoglobulin classes, although this usually does not translate into an increased risk of bacterial infection.

Treating chronic ITP

Most children with chronic ITP require no treatment (Table 6). Their platelet counts generally range (and fluctuate widely) between 20,000 and 80,000/µL, and they have few bleeding problems except for easy bruising and occasional crops of petechiae. Although a noninterventionist approach to managing chronic ITP is usually advisable, some hematologists believe in making all possible efforts to maintain a platelet count above 30,000 or 40,000/µL. The pharmacologic approaches these physicians use are described below.

The general pediatrician can direct ongoing management of chronic ITP. An initial hematology consultation is advisable in all children with probable chronic ITP to rule out alternative diagnoses and assist with overall management strategy.

Drugs. If a temporary rise in platelet count is desiredfor example, when thrombocytopenia worsens during a viral infection or prior to an elective surgical procedureprednisone, anti-D, or IV IgG should be administered according to the dosage schedules already outlined. Chronic high-dose steroids are contraindicated, and low-dose alternate-day glucocorticoid therapy is usually ineffective. Some physicians advocate using regular (every three to six weeks) infusions of IV IgG or anti-D to maintain the platelet count above 30,000 or 40,000/µL or to avoid splenectomy.23 This approach, however, is costly and unwieldy.

Splenectomy. The treatment of choice for children with severe or symptomatic chronic ITP is splenectomy, which ultimately will be required in as many as one third of patients with chronic ITPespecially teenagers. The procedure is recommended when the thrombocytopenia and bleeding signs (or the fear of hemorrhage) are severe enough to interfere appreciably with the youngster's lifestyle. For some children, a platelet count as low as 20,000/µL is well tolerated, whereas active adolescents whose platelet counts average 50,000/µL may require splenectomy if they very much want to participate in contact sports.

Splenectomy removes both the main site of platelet destruction and a major location of antiplatelet antibody production. The laparoscopic technique is now preferred to the classic open procedure.24 Patients should receive prednisone beginning about seven days before splenectomy (or IV IgG if prednisone has proven ineffective in raising the platelet count). Even if the platelet count remains low, hemorrhage during or after splenectomy is infrequent, and platelet transfusions are infrequently required.

About 80% of children with ITP have a longstanding or permanent remission following splenectomy.25 The remaining 20% of patients respond poorly or not at all. Unfortunately, response to surgery cannot be accurately predicted.

To reduce the risk of sepsis, all patients should receive a preoperative dose of polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine and (if not inoculated earlier) conjugated Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine. To further reduce the risk of septicemia due to Streptococcus pneumoniae, patients should take prophylactic penicillin V (250 mg twice daily) for at least three years following splenectomy and be reminded to seek immediate medical attention if they have a high fever and chills.

Patients who still have markedly symptomatic thrombocytopenia despite splenectomy may require other therapeutic approaches.21 Data on their effectiveness in the pediatric ITP population are limited and unconvincing, however.

Chronic ITP's natural history. Most children with chronic ITP fare quite well without therapy. Moreover, many fully recover. Several recently published series and personal experience confirm that most children with chronic ITP eventually (often after many years) achieve a platelet count of more than 100,000/µL, eliminating virtually all bleeding signs.2628 However, active children who have ITP with persistently low platelet counts may find it unacceptable to wait the many years sometimes necessary for a complete remission. In such cases a splenectomy should be employed.25

Clinical trials needed

Unfortunately, no randomized controlled studies have yet been conducted to determine which therapy, if any, is best for children with newly diagnosed or chronic ITP. The few randomized trials that have been performed have assessed platelet count as the only outcome measure. Future studies must consider bleeding signs and symptoms, side effects of therapy, cost of treatment, and quality of the patient's and parent's life, in addition to platelet count, to determine which therapy is best for each child. Without data from clinical trials, practitioners have had to rely instead on practice guidelines recommended by experts29,30 and surveys of current practice patterns.3,13 Both of these approaches have substantial limitations.31,32

A good outlook

For most patients, acute or chronic ITP is a nuisance rather than a truly serious hematologic disorder, resolving with minimal or no therapy. Several therapeutic avenues are open to children with symptomatic disease, but their success varies, and serious morbidity and fatalities are rare indeed. When dealing with ITP, remember to treat the child, not the platelet count.

REFERENCES

1. Ballin A, Kenet G, Tamaro H, et al: Infantile idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1990;7:323

2. Buchanan GR: Childhood acute thrombocytopenic purpura: How many tests and how much treatment required? J Pediatr 1985;106:928

3. Dubansky S, Oski F: Controversies in the management of acute idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: A survey of specialists. Pediatrics 1986;77:49

4. Dubansky AS, Boyett JM, Falletta J, et al: Isolated thrombocytopenia in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A rare event in a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Pediatrics 1989;84:1068

5. Calpin C, Dick P, Poon A, et al: Is bone marrow aspiration needed in acute childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura to rule out leukemia? Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1998;152:345

6. Gernsheimer T, Stratton J, Ballem PJ, et al: Mechanisms of response to treatment in autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1989;320:974

7. Buchanan GR, Hoftkamp CA: Prednisone therapy for children with newly diagnosed idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: A randomized clinical trial. Am J Pediatric Hematol Oncol 1984;6:355

8. Blanchette VS, Luke B, Andrew M, et al: A prospective, randomized trial of high dose intravenous immune globulin G therapy, oral prednisone therapy, and no therapy in childhood acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura. J Pediatr 1993;123:989

9. Imbach P, Berchtold W. Hirt A, et al: Intravenous immunoglobulin vs. oral corticosteroids in acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura in childhood. Lancet 1985;2:464

10. Van Hoff J, Ritchey AK: Pulse methylprednisolone therapy for acute childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Pediatr 1988;113:563

11. Imbach P, d'Apuzzo V, Hirt A, et al: High-dose intravenous gammaglobulin for idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura in childhood. Lancet 1981;1:1228

12. Bussel JB, Fitzgerald-Pedersen J, Feldman C: Alternation of two doses of intravenous gammaglobulin in the maintenance treatment of patients with immune

thrombocytopenic purpura: More is not always better. Am J Hematol 1990;33:184

13. Vesely S, Buchanan GR, Cohen A, et al: Self reported diagnostic and management strategies in childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Results of a survey of practicing pediatric hematology-oncology specialists. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1999 (in press)

14. Gurwitch KD, Goldwire MA, Baker CJ: Intravenous immune globulin shortage: Experience at a large children's hospital. Pediatrics 1998;133:645

15. Tarantino MD, Madden RM, Fennewald DL, et al: Treatment of childhood acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura with anti-D immune globulin or pooled immune globulin. J Pediatr 1999;134:21

16. Blanchette VS, Imbach P, Andrew M, et al: Randomized trial of intravenous immunoglobulin G, intravenous ant-D, and oral prednisone in childhood acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Lancet 1994;344:703

17. Kattamis AC, Shankar S, Cohen AR: Neurologic complications of treatment of childhood acute immune thrombocytopenic purpura with intravenously administered immunoglobulin G. J Pediatr 1997;130:281

18. Medeiros D, Buchanan GR: Major hemorrhage in children with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Immediate response to therapy and long-term outcome. J Pediatr 1998;133:334

19. Lilleyman JS: Intracranial hemorrhage in idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Arch Dis Child 1994;71:251

20. Lilleyman JS: Management of childhood idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol 1999;105:871

21. Medeiros D, Buchanan: Current controversies in the management of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura during childhood. Pediatr Clin North Am 1996;43:757

22. Pappo AS, Fields BW, Buchanan GR: Etiology of red blood cell macrocytosis during childhood: Impact of new diseases and therapies. Pediatrics 1992;89:1063

23. Bussel JB, Schulman I, Hilgartner MW, et al: Intravenous use of gamma globulin in the treatment of chronic immune thrombocytopenic purpura as a means to defer splenectomy. J Pediatr 1983;103:651

24. Farah RA, Rogers ZR, Thompson WR, et al: Comparison of laparoscopic and open splenectomy in children with hematologic disorders. J Pediatr 1997; 131:41

25. Mantadakis E, Buchanan GR: Elective splenectomy in children with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP). J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 1999 (in press)

26. Tait RC, Evans DIK: Late spontaneous recovery of chronic thrombocytopenia. Arch Dis Child 1993;68:681

27. Walker RW, Walker W: Idiopathic thrombocytopenia, initial illness, and long-term follow-up. Arch Dis Child 1984;59:316

28. Reid MM: Chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: Incidence, treatment, and outcome. Arch Dis Child 1995;72:125

29. George JN, Woolf SH, Raskob GE, et al: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura: A practice guideline developed by explicit methods for The American Society of Hematology. Blood 1996;88:3

30. Eden OB, Lilleyman JS: Guidelines for management of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Arch Dis Child 1992;67:1056

31. Buchanan GR: Acute idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpuramanagement in childhood. Blood 1997;89:1464

32. Bolton-Maggs PHB: Acute idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpuramanagement in childhood. Blood 1997;89:1465

ACCREDITATION

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Jefferson Medical College and Medical Economics, Inc.

Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, as a member of the Consortium for Academic Continuing Medical Education, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to sponsor continuing medical education for physicians. All faculty/authors participating in continuing medical education activities sponsored by Jefferson Medical College are expected to disclose to the activity audience any real or apparent conflict(s) of interest related to the content of their article(s). Full disclosure of these relationships, if any, appears with the author affiliations on page 1 of the article.

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION CREDIT

This CME activity is designed for practicing pediatricians and other health-care professionals as a review of the latest information in the field. Its goal is to increase participants' ability to prevent, diagnose, and treat important pediatric problems.

Jefferson Medical College designates this continuing medical educational activity for a maximum of one hour of Category 1 credit towards the Physician's Recognition Award (PRA) of the American Medical Association. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent in the educational activity.

This credit is available for the period of April 15, 2000, to April 15, 2001. Forms received after April 15, 2001, cannot be processed.

Although forms will be processed when received, certificates for CME credits will be issued every four months, in March, July, and November. Interim requests for certificates can be made by contacting the Jefferson Office of Continuing Medical Education at 215-955-6992.

HOW TO APPLY FOR CME CREDIT

1. Each CME article is prefaced by learning objectives for participants to use to determine if the article relates to their individual learning needs.

2. Read the article carefully, paying particular attention to the tables and other illustrative materials.

3. Complete the CME Registration and Evaluation Form below. Type or print your full name and address in the space provided, and provide an evaluation of the activity as requested. In order for the form to be processed, all information must be complete and legible.

4. Send the completed form, with $20 payment if required (see Payment, below), to:

Office of Continuing Medical Education/JMC

Jefferson Alumni Hall

1020 Locust Street, Suite M32

Philadelphia, PA 19107-6799

5. Be sure to mail the Registration and Evaluation Form on or before April 15, 2001. After that date, this article will no longer be designated for credit and forms cannot be processed.

FACULTY DISCLOSURES

Jefferson Medical College, in accordance with accreditation requirements, asks the authors of CME articles to disclose any affiliations or financial interests they may have in any organization that may have an interest in any part of their article. The following information was received from the author of "ITP: How much treatment is enough?"

George R. Buchanan, MD, is a consultant to Centeon.

Send thet completed form to:

Office of Continuing Mediacal Education/JMC. Jefferson Alumni Hall, 1020 Locust Street, Suite M32,

Philadelphia, PA 19107-7699.

THE AUTHOR is Professor of Pediatrics, Children's Cancer Fund Distinguished Chair in Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas. Dr. Buchanan is a consultant to Centeon.

George Buchanan. ITP: How much treatment is enough?.

Contemporary Pediatrics

2000;4:112.