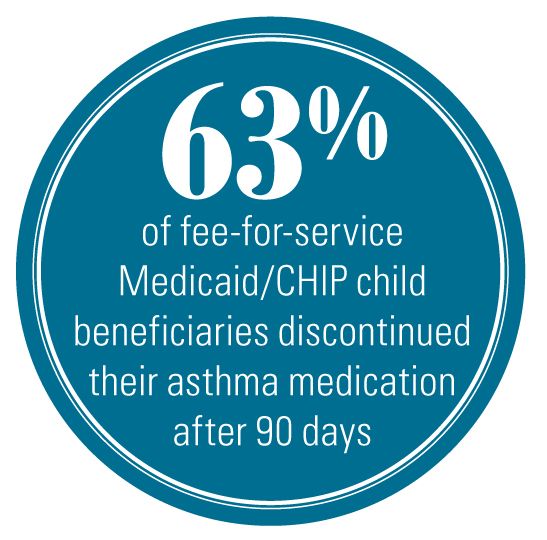

Lack of asthma medication compliance seen in CHIP and Medicaid patients

Sixty-three percent of fee-for-service Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) child beneficiaries had discontinued their asthma medication after 90 days from the start of their first prescription, according to new research from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

Sixty-three percent of fee-for-service Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) child beneficiaries had discontinued their asthma medication after 90 days from the start of their first prescription, according to new research from the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS).

At 190 days, only 15% of the sample had not dropped the medications, said the NCHS report available early online. Minority children and those from disadvantaged households were at higher risk.

The researchers linked National Health Interview Survey records for 4262 children aged 2 to 17 years with the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) files from 1999 to 2008 that contain Medicaid and CHIP data for claims, including pharmacy claims to see if children had prescriptions refilled for them.

The investigators, led by David E. Capo-Ramos, MD, MPH, say the findings suggest “earlier follow-up would be necessary to assess the effects of preventive asthma medications on asthma symptoms and potentially to help prevent discontinuation.” Capo-Ramos, who was with NCHS at the time of the study, is currently with Abarca Health in San Juan, Puerto Rico.

According to the study, “Compared to regimens including both ICS [inhaled corticosteroids] and leukotriene modifiers, discontinuation was greater for those on ICS without leukotriene modifiers or on other preventive asthma medications.”

Bob Q. Lanier, MD, executive medical director of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, is not at all surprised. Getting people of all types to take their asthma medications, he says, is part of “the Gordian knot of compliance.”

Even doctors with asthma often don’t take their medications, Lanier points out. The statistics are similar for persons with various kinds of insurance and for persons who pay little or nothing for medications.

One problem, Lanier says, is that when patients with asthma feel well, they don’t necessarily want to go to a physician to get their problems checked.

Bradley Chipps, MD, medical director of respiratory therapy and the cystic fibrosis center at Sacramento’s Sutter Medical Center, emphasizes that these patients need regularly scheduled physician visits. However, he also says that often primary care physicians don’t find the time to educate patients and don’t use the tools developed for the purpose.

Lanier notes there have been a number of programs to improve compliance and they work well for a time, but they don’t sustain the improvement. “We just haven’t found the right answer,” he says.

He also indicates that greater numbers of asthma and allergy medications are expected to soon become available over the counter, and that may make compliance issues more difficult. “Then the prescriptive power that [physicians] have to refill medicines and to encourage education and compliance is not there much anymore,” he says.

Lanier did note, however, that in many cases guidelines in this country call for patients to take allergy and asthma medications on an ongoing basis, yet in other countries patients are told to take them “as needed.”

“Maybe we don’t know as much as we thought we did,” he says.

“The biggest issue, we feel, in childhood asthma [is] mild infections that are episodic, and when they come it’s pretty difficult to know if having used their inhaled steroids would have prevented the acute attack,” Lanier explains.

Ms Foxhall is a freelance writer in the Washington, DC, area. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that might have an interest in any part of this article.