Managing eczema

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis is on the rise, ranging from 10% to 20% in the United States and other developed countries.

Prevalence of atopic dermatitis is on the rise, ranging from 10% to 20% in the United States and other developed countries.1

However, managing the severity of atopic dermatitis is no easy task. Flares come and go, and the reasons for uncomfortable exacerbations can be complex and hard to pinpoint. Making treatment more challenging is “steroid phobia,” also known as “corticosteroid phobia,” a concern among many parents and others about the safety of topical corticosteroids, the mainstay treatment for children with moderate to severe disease.2

Finding the best ways in which to manage patients with atopic dermatitis is critical, not only to relieve physical symptoms of the disease, but also to mitigate the psychosocial impact on children’s and families’ lives, according to Amy Paller, MD, professor and chair of dermatology and professor of pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois.

“We’ve always known that there are severe psychosocial effects.3 [These range] from the highly visible lesions to the fact that these children don’t sleep well, if they sleep. It’s difficult in school because they’re falling asleep and that makes them different. They have attentional issues at school. They don’t feel comfortable playing or doing sports because they’re so much itchier when they get hot,” Paller says. “There are also neurocognitive issues with atopic dermatitis.”

Quality of life is profoundly affected in children with moderate to severe disease, according to Paller.4 “[T]he quality of life reported [by these kids] is [similar to] what we see with many of the chronic diseases, such as diabetes and seizures,” she says.

Increasing understanding

Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, chief of pediatric dermatology and professor of pediatrics and medicine (dermatology), at the University of California, San Diego, and Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, California, says that atopic dermatitis advances and research have improved understanding of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of the disease.

“Over the last several years, identification of mutations in the skin responsible for skin barrier dysfunction, associated with the dry skin of eczema, as well as a setup for its inflammation, have been emphasized,” says Eichenfield, an author on the atopic dermatitis guidelines released in 2014 by the American Academy of Dermatology.

“Research has shown there are mutations in certain genes expressed in the epidermis that fundamentally influence the skin barrier function. Filaggrin gene mutations have been shown to have a strong predictive value for higher risk of development of atopic dermatitis, as well as increased rates of asthma, allergic rhinitis, [immunoglobulin E] sensitization, as well as more severe atopic dermatitis that can persist into late childhood and adulthood,” he says.

Eczema is a phenotype. Classic atopic dermatitis usually starts in early childhood. Whether adult onset atopic dermatitis is the same or a different disease is unclear, according to Elaine C. Siegfried, MD, professor of pediatrics and dermatology, Saint Louis University, Missouri. Also, the jury is still out on whether atopic dermatitis is a primary inflammatory disease or a primary barrier disease, she says.

“The pathogenesis is likely related to dysfunction in both systems. For some it’s probably primary inflammatory and for other people it’s probably primary barrier,” Siegfried says, “but the role of the cutaneous microbiome is being increasingly recognized as an important cofactor for both skin barrier and immune function.”

From a clinical standpoint, the knowledge about skin barrier dysfunction reassures physicians that an approach emphasizing good skin care and liberal use of moisturizers can help to minimize the impact of the disease, according to Eichenfield.

Infection can occur with atopic flares, but antibiotics are better left to treat skin infections, rather than try to prevent them, says Eichenfield. “Generally, in nonaffected atopic dermatitis the broad use of antibiotics is not recommended. However, infected eczema might benefit from systemic treatments,” she says.

Treatment options still limited

The biggest breakthrough in atopic dermatitis treatment has been the development of topical corticosteroids, according to Siegfried. “Before [topical corticosteroids], treatment was incredibly difficult. After topical corticosteroids were developed, acute relief was possible for the majority of patients,” she says.

However, long-term use of topical corticosteroid monotherapy carries the risk of adverse effects. Potential problems include cyclic rebound of the skin disease, cutaneous atrophy, and corticosteroid contact allergy.

“That’s why steroid-sparing alternatives have been developed,” Siegfried says, “and it’s wonderful to have those options. The most well-studied are the topical calcineurin inhibitors Elidel and Protopic.”

The public’s phobia surrounding topical corticosteroid use, however, is more fear based than research based, according to Siegfried.

The perceived dangers of topical corticosteroids often lead to noncompliance. According to research published in October 2011 in the British Journal of Dermatology, parents and adult patients with atopic dermatitis who were surveyed reported fearing topical corticosteroids and more than a third admitted nonadherence to treatment.5

“You can overuse corticosteroids, but if you don’t use them at all it can be very difficult to keep the disease under control,” Siegfried says. “In my practice . . . corticosteroids are always first line. They’re the most well studied and have been around for the longest period of time. [I]n people whose disease can’t be controlled on a safe amount of corticosteroids, you have to add a steroid-sparing agent. Options include a calcineurin inhibitor or phototherapy. Some people still use tar, although most patients don’t like it and there’s a concern about carcinogenicity.”

Calcineurin inhibitors are safe, well tolerated, and readily available, notes Siegfried. “They don’t work as fast or as dramatically as corticosteroids but they maintain skin health and help control inflammation long term, without causing cutaneous atrophy,” she says.

Peter Lio, MD, assistant professor of clinical dermatology and pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and director of the Chicago Integrative Eczema Center, is among the physicians working with the National Eczema Association to address steroid phobia with medical evidence and advice.

“We don’t want people to think we’re not hearing them; we hear them. Steroid phobia is real and it’s important to treat these medicines with respect because they are powerful,” Lio says. “However, what’s wonderful is, when used correctly, topical steroids can give tremendous relief and help break the scratch-itch cycle without causing significant problems.”

Lio’s advice to pediatricians: Manage patients on topical corticosteroids to prevent adverse effects. “We never want to just give them a year’s supply and say ‘see you later.’ We want to have them come back. I interrogate them at each visit: ‘How much are you using?’ If they’re using too much, we say we need to use something else,” he says.

Steroid-sparing agents

Topical calcineurin inhibitors are an effective option for some patients with atopic dermatitis, but prescribing can be a challenge. A black box warning about a potential cancer risk limits access to the option for children with atopic dermatitis, according to Siegfried.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical calcineurin inhibitors to treat atopic dermatitis and children (tacrolimus ointment in 2000 and pimecrolimus cream in 2001). A few years later, the FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee implemented a black box warning for both drugs because of the lack of long-term safety data and the potential risk of the development of malignancies.6

The warning states the use of these medications may increase the risk of certain cancers, specifically skin cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The American Academy of Dermatology, however, published this quote by Eichenfield: “[P]atients should know that studies have not demonstrated an increased cancer risk from [topical calcineurin inhibitor] use.”

“New drug development for atopic dermatitis suffered from the black box warning on calcineurin inhibitors, so there were no drugs in the pipeline for a long time,” Siegfried says. “Finally, people are starting to recognize the epidemiologic importance and unmet medical need of [atopic dermatitis]. So, we now have new drugs in the pipeline.”

Among those drugs is dupilumab, a human monoclonal antibody that blocks interleukin-4 and interleukin-13. An adult trial looking at dupilumab, an injectable drug, for the treatment of atopic dermatitis showed promising results.7

“Another promising drug is a phosphodiesterase type 4 (PDE-4) inhibitor. It is currently in phase III trials as a topical product for mild to moderate atopic dermatitis,” Siegfried says.

Anacor Pharmaceuticals (Palo Alto, California) announced positive results from a phase II trial in December 2012 following a trial on adolescents with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis using its boron-based PDE-4 inhibitor, AN2728.

Other research is going on in the areas of atopic dermatitis biomarkers and triggers, and in the development of better tools for judging treatment efficacy in research trials, according to Siegfried. “A sizable group of dedicated clinicians and investigators is working with various agencies to try to define the best measure of atopic dermatitis improvement,” she says. “Implementing a uniform measure into new clinical trials protocols is very important in order to have a uniform measure to compare different drugs.”

At-home skin care remedies

The wet wrap is among the therapies that patients can do at home to effectively manage atopic dermatitis. Researchers demonstrated benefit from wet wrap use in 72 children with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.8 They used wet wrap therapy as an “acute intervention in a supervised multidisciplinary [atopic dermatitis] treatment program with lasting benefit 1 month after discontinuing this intervention,” according to the study.

“In my experience, wet wraps are a very effective way to achieve acute improvement. [They offer] short-term relief, but are not a long-term solution,” Siegfried says.

Intermittent use of bleach baths, with dilute sodium hypochlorite, helps as an adjunctive therapy for atopic dermatitis, studies show. In 1 feasibility study of 18 children with atopic dermatitis, patients washed 3 days each week for 12 weeks with the sodium hypochlorite-containing cleansing body wash.9 The investigators reported: “The significant reductions in clinical disease severity scores with use of this formulation are encouraging.”

The use of oral probiotics is also getting attention, but Siegfried says data demonstrating significant efficacy is scant, mostly supporting modest benefit when used during third-trimester pregnancy for preventing atopic dermatitis in infants at high risk of the disease, suggested by a strong family history.

“Vitamin D is another area that needs a lot more study. Kids in general have low serum vitamin D levels, based on the current definition. Vitamin D is incredibly safe, so giving a supplement [or applying topical vitamin D] to kids who are deficient couldn't hurt,” Siegfried says

Confounding factors

There are so many other things that play a role in eczema flares, including stress; other atopic diseases such as eosinophilic esophagitis or eosinophilic gastroenteritis; as well as other immune deficiencies that lead to recurrent infections such as eczema herpeticum, which can be a difficult problem for children with atopic dermatitis, Siegfried points out. “I think it takes a lot of experience to recognize relevant triggers. There are so many possibilities,” she says.

While food and environmental allergens drive the disease in only a small minority of children with atopic dermatitis, most parents focus on these variables, Siegfried says. “Many parents believe that if they could just find the one trigger-a food or plant or inhaled allergen or something-the entire spectrum of atopic problems will disappear, but the great majority of patients do not have a single trigger,” she says.

Educating patients and families about the disease plays a crucial role in disease management, according to Eichenfield. “There is an international movement emphasizing therapeutic patient education of atopic dermatitis, recognizing that like other chronic diseases, giving patients and families the skill to manage their life in the best possible way to mediate the course of disease can be highly useful,” she says.

This includes educating patients and families about appropriate and safe steroid strengths and safety, and integrating these therapies into regimens of care, he adds.

REFERENCES

1. Totri CR, Diaz L, Eichenfield LF. 2014 update on atopic dermatitis in children. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2014;26(4):466-471.

2. Kim KH. Clinical pearls from atopic dermatitis and its infectious complications. Br J Dermatol. 2014;170 Suppl 1:25-30.

3. Chamlin SL, Chren MM. Quality-of-life outcomes and measurement in childhood atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30(3):281-288.

4. Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):145-151.

5. Aubert-Wastiaux H, Moret L, Le Rhun A, et al. Topical corticosteroid phobia in atopic dermatitis: a study of its nature, origins and frequency. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(4):808-814.

6. Ring J, Möhrenschlager M, Henkel V. The US FDA 'black box' warning for topical calcineurin inhibitors: an ongoing controversy. Drug Saf. 2008;31(3):185-198.

7. Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130-139.

8. Nicol NH, Boguniewicz M, Strand M, Klinnert MD. Wet wrap therapy in children with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in a multidisciplinary treatment program. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):400-406.

9. Ryan C, Shaw RE, Cockerell CJ, Hand S, Ghali FE. Novel sodium hypochlorite cleanser shows clinical response and excellent acceptability in the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30(3):308-315.

Resources for Pediatricians

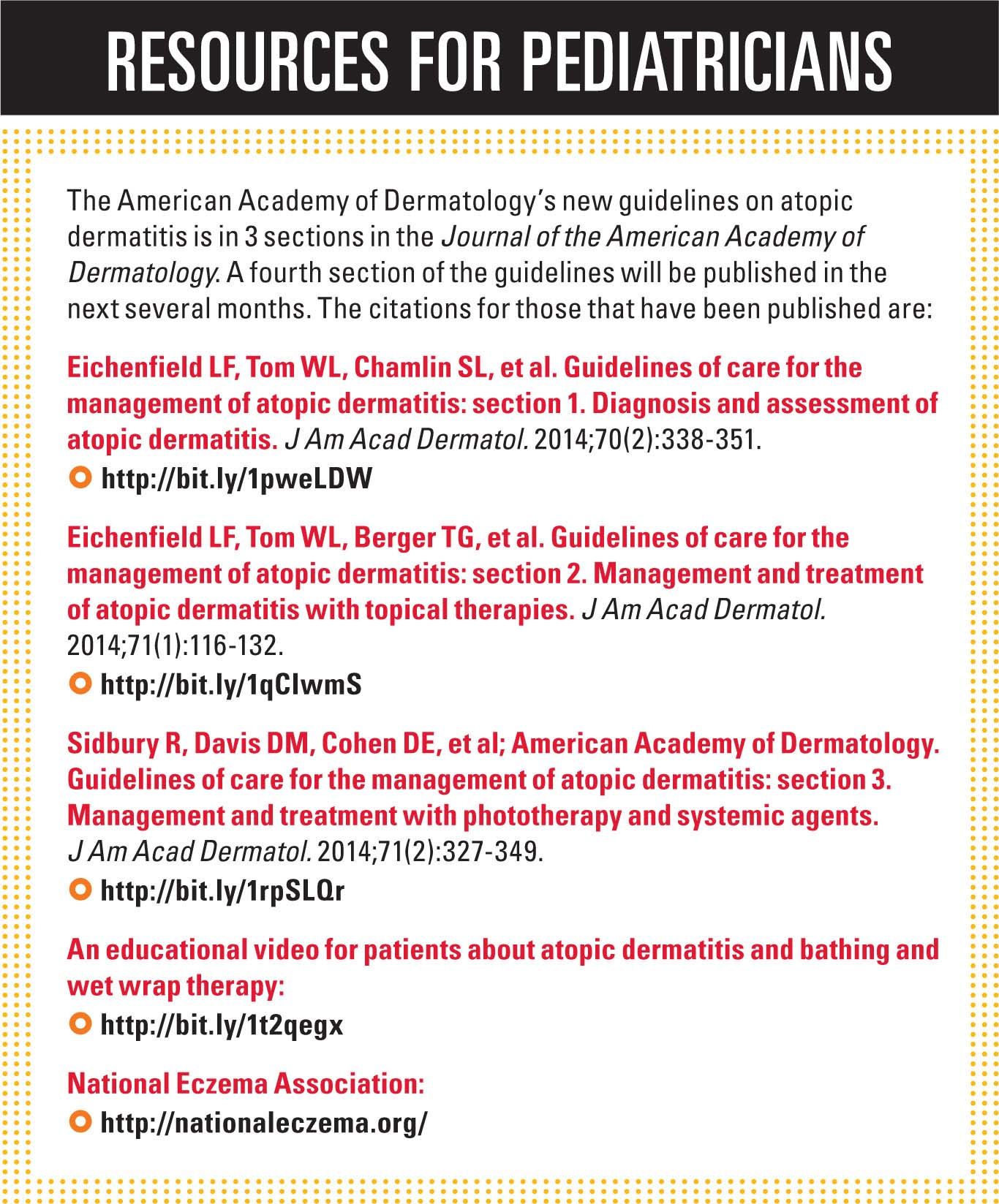

The American Academy of Dermatology’s new guidelines on atopic dermatitis is in 3 sections in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. A fourth section of the guidelines will be published in the next several months. The citations for those that have been published are:

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Chamlin SL, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(2):338-351.

Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(1):116-132.

Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, et al; American Academy of Dermatology. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327-349.

An educational video for patients about atopic dermatitis and bathing and wet wrap therapy:

National Eczema Association:

Alternative treatments for eczema

Editor's note: This article was previously published online in our sister publication Dermatology Times, September 19, 2014.

Peter Lio, MDEczema patients and their families often come to Peter Lio, MD, assistant professor of clinical dermatology and pediatrics, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, Illinois, and director of the Chicago Integrative Eczema Center, looking for relief through alternative treatments.

“Sometimes people come in and say, ‘I don’t want to use any Western medicine,'" he relates, “and I’ll say, if it’s the mildest eczema, perhaps we can get by. But for anything more severe, we really need to do this as part of a plan with the hopes of minimizing the amount of more powerful medicines by strengthening the skin and doing these other good things.”

Here are some of the remedies his patients suggest with Dr. Lio’s corresponding thumbs up, jury’s out, and thumbs down determinations on them.

THUMBS UP1. Sunflower seed oil

(Lio’s favorite)

“It comes in a number of different forms. There are some products that have it built in. There are some bath oils that have it. I’m happy with any of those, but I really like just the pure sunflower seed oil,” he says. Apply it to damp skin, twice a day. Sunflower seed oil naturally boosts the skin barrier function and has anti-inflammatory properties.

There is no downside to using it, the dermatologist says. “There is a theoretical risk that putting things on the skin that we eat can potentially make us allergic to them, but it does not appear to be a significant risk with sunflower seed oil, in my experience. If someone has a known allergy to sunflower seeds, however, then I would definitely avoid it,” he says.

2. Coconut oil

People can buy it off the shelf, but should make sure it’s virgin or cold-pressed coconut oil. Why? There might be residues of extraction chemicals in other coconut oil types.

Apply it once or twice a day to damp skin, if possible. Coconut oil has been shown to reduce staph bacteria on the skin and it acts as an emollient, according to Lio.

How about kids with nut allergies? “Coconut is a distant cousin of tree nuts. Some allergists put it in that group. It’s a rare allergen, but certainly avoid it if you’re allergic to coconuts,” Lio says.

3. Acupressure

Lio uses just 1 acupressure point and has found it makes a difference for his patients. Patients or parents can apply the pressure at home, once they learn how, he says. “Some say that it is simply working as a distraction. It’s something to do with your hands rather than scratch,” Lio says. “I am okay with that, but it may have direct effect on the mechanisms of the itch itself.”

Lio was senior author on a paper looking at acupressure’s efficacy in eczema.1 The researchers compared a standard care control group of adults with atopic dermatitis to an intervention group performing a specific type of acupressure for 3 minutes, 3 times a week for 4 weeks. Twelve adults finished the study. Those in the intervention group showed improvement in pruritus and lichenification, whereas people in the control group experienced no change.

JURY'S OUT1. Probiotics

The data has been up and down. There are some very promising studies that show prevention of atopic dermatitis, and some in which probiotics even seem to help existing eczema. However, there are also studies in which it doesn’t seem to do much at all. It may be there is more to learn about the right types of probiotics, the right patients, and the right dosing schedule, and this continues to be an exciting area, according to Lio.

Lio was coauthor of an article in Practical Dermatology, May 2014, “Probiotics: the search for bacterial balance,” in which the researchers looked at the use of probiotics for the prevention and treatment of eczema. He and his coauthors report a 2010 review of trials that found insufficient data to endorse the use of probiotics to prevent or manage atopic dermatitis.2 In contrast, a 2012 meta-analysis of trials found probiotic usage was associated with about 20% decreased atopic dermatitis incidence in children.3

2. Dietary modification, in particular gluten-free, casein-free (milk protein-free) diet

“I have many patients who have been instructed by their integrative or holistic practitioner to cut diary and gluten. To some extent, I think that big dietary changes can be good, overall, for some people, and can effect sweeping changes in their life. However, while I have patients do it in earnest, my honest opinion is it’s not the solution for most. I wish it were. It would be great if we could just make a diet change,” Lio says. “It sure seems to work for some people, but it sadly doesn’t work for everybody.”

3. Chinese herbs

“There are some quite exciting studies that show great improvement in some patients, but we really need to learn more about it. And we need to figure out how we can do this in a more standard fashion because it’s not easy to apply to everybody, especially outside of a traditional Chinese medicine framework,” Lio says.

THUMBS DOWN1. Evening primrose oil

It’s a nice oil with good properties but it hasn’t been shown to help with eczema, according to Lio.

2. Borage oil

Same thing. “A lot of people want to take it by mouth but it has not really been shown to help,” he says.

3. Homeopathy

“It’s compelling and some patients swear by it, but I think there’s enough data to say, overall, homeopathy is not something we can recommend in good faith,” Lio says.

REFERENCES

1. Lee KC, Keyes A, Hensley JR, Gordon JR, Kwasny MJ, West DP, Lio PA. Effectiveness of acupressure on pruritus and lichenification associated with atopic dermatitis: a pilot trial. Acupunct Med. 2012;30(1):8-11.

2. van der Aa LB, Heymans HS, van Aalderen WM, Sprikkelman AB. Probiotics and prebiotics in atopic dermatitis: review of the theoretical background and clinical evidence. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(2 pt 2):e355-e367.

3. Pelucchi C, Chatenoud L, Turati F, et al. Probiotics supplementation during pregnancy or infancy for the prevention of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2012;23(3):402-414.

Ms Hilton is a medical writer who has covered health and medicine for 25 years. She resides in Boca Raton, Florida. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.