Marketplace or Medicaid? What to do with kids

The number of medically uninsured children between 2008 and 2012 dropped to 5.3 million, and the coverage rate rose to 92.8%, according to the US Census Bureau American Community Survey. That might be the good news, but currently 70% of uninsured children are eligible but not enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), says the Urban Institute.

The number of medically uninsured children between 2008 and 2012 dropped to 5.3 million, and the coverage rate rose to 92.8%, according to the US Census Bureau American Community Survey.

That might be the good news, but currently 70% of uninsured children are eligible but not enrolled in Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), says the Urban Institute.

The Institute’s Health Insurance Policy Simulation Model indicates that under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), 75% of parents who are enrolled in a subsidized health insurance exchange plan will have a child eligible for Medicaid or CHIP.

There is progress to be made in curing the ills of the healthcare system. The process by which parents seek coverage in the new exchanges while their children qualify for Medicaid or CHIP is confusing for many families, along with enrolling and renewing eligible uninsured children and dealing with “churn,” the annual shifting between Medicaid and marketplace policies.

As director of CHIP in New Hampshire for 15 years, Tricia Brooks, who now serves as research associate professor at the Georgetown University Center for Children and Families, Washington, DC, knows first hand about the potential problems associated with Medicaid, but she also recognizes the program's benefits.

Split coverage for families

Brooks is not convinced that split coverage within a family is such a major issue. She points to the robust benefits provided by Medicaid, including the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment benefit provided to children aged younger than 21 years, which the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) calls the “gold standard.”

“Those benefits are more comprehensive than the exchange’s essential health benefits, or commercial insurance,” she says.

Brooks also praises Medicaid over private insurance for its more streamlined approach to management, presenting fewer barriers to accessing care, and limiting cost share to nominal charges.

All in all, Brooks says that although coverage may be split between 2 different systems, both with their own requirements for accessing care and potentially different provider networks, Medicaid presents fewer challenges once a beneficiary is enrolled.

By contrast, Margaret Murray, CEO of the Association of Community Affiliated Plans (ACAP), Washington, DC, is concerned that parents covered under the exchange while their children are in Medicaid or CHIP-she estimates 41%-may be confused in seeking healthcare. That would mean different providers and copayments and 2 points of contact, she says.

She also recommends that consumers be made aware of insurers that serve in both the exchange and Medicaid.

The ACAP estimates that there are 286 qualified health plan (QHP) issuers nationally, and of these, 117 (42%) also operate Medicaid managed care organizations in the same state.

Handling split coverage in the provider setting

With a split in coverage, there definitely can be some confusion once parents, with children in hand, face the registration staff at their local pediatrician’s office, says Kenneth Schellhase, MD, medical director for the Children’s Community Health Plan in Wisconsin and a family practitioner.

Confusion reigns when parents no longer qualify for Medicaid-their incomes are above the federal poverty level for the state or they have neglected to renew their coverage-but their children remain eligible for Medicaid.

Schellhase points to a less educated and less literate population and unfamiliarity with new ACA rules as parts of the problem.

“[Physicianss'] staff members should be able to explain ACA regulations and direct parents to the best coverage options for both parents and children,” Schellhase says, “preferably during a private conversation.”

Schellhase notes 2 scenarios that could potentially lead to somewhat “delicate” issues-when parents are undocumented and their children are US citizens, and if parents’ income has dropped, either scenario pushing them back into Medicaid coverage or shifting their children to the government program.

“It is difficult to answer questions such as ‘why aren’t you covered’ when parents aren’t citizens or face the stigma of enrolling in Medicaid,” he says. “The pediatric staff must be able to broach these issues without betraying any sign of surprise and not send a message that something is wrong.”

Brooks also offers some practical advice for provider offices. “Since the front office always confirms the source of coverage for the patient being seen, staff could simply ask if any member of the family is uninsured, and if the answer is ‘yes,’ have a supply of brochures or fact sheets to give to individuals,” she says. “Or staff might hand out the brochure and make the statement that ‘if any family member is uninsured, there are new affordable coverage options.’”

“But it gets a little tricky in states that aren’t expanding Medicaid because [then] there is the coverage gap,” Brooks says. “Also, for those who qualify for marketplace coverage, there is a deadline looming and that has impact on how an office might want to do outreach.” (Open enrollment for 2014 ends March 31.)

Brooks says pediatricians might be concerned if a patient is a new parent and shows signs of postnatal depression or other illness that could affect the child’s health and well-being. “Pediatricians, perhaps more than other providers, know the impact of socioeconomic circumstances on children’s health,” she says.

Brooks adds that because pediatricians might not be aware of the insurance status of their patients until they are suggesting a test or treatment, and the parent expresses concern about costs, it is important for the staff to work with families to enroll them in coverage or meet other needs the family may have, such as services from a social worker.

Unfortunately, reimbursement for those services is not common and that inhibits the provider from becoming a robust "health home" for kids, and not just a medical home, she says.

Reimbursement on the line

Although Medicaid pays a lower reimbursement rate, the ACA provided 100% federal funding for states to boost Medicaid reimbursement rates for primary care to Medicare levels. Schellhase says is difficult to see how this might play out for pediatricians in each state, depending both on the number of new Medicaid beneficiaries in states with expansion and on the size of enrollment in the exchanges. Reimbursement depends on the issuer.

“However, the higher funding for Medicaid is running out at the end of 2014, so it will be important for stakeholders to advocate for their states to maintain the higher reimbursement,” Brooks says. “I would think pediatricians would want to engage in that effort.”

Both Schellhase and Brooks agree that because the Medicaid coverage rate for children is already high in many states, the payer mix for providers might not change significantly.

As the system churns

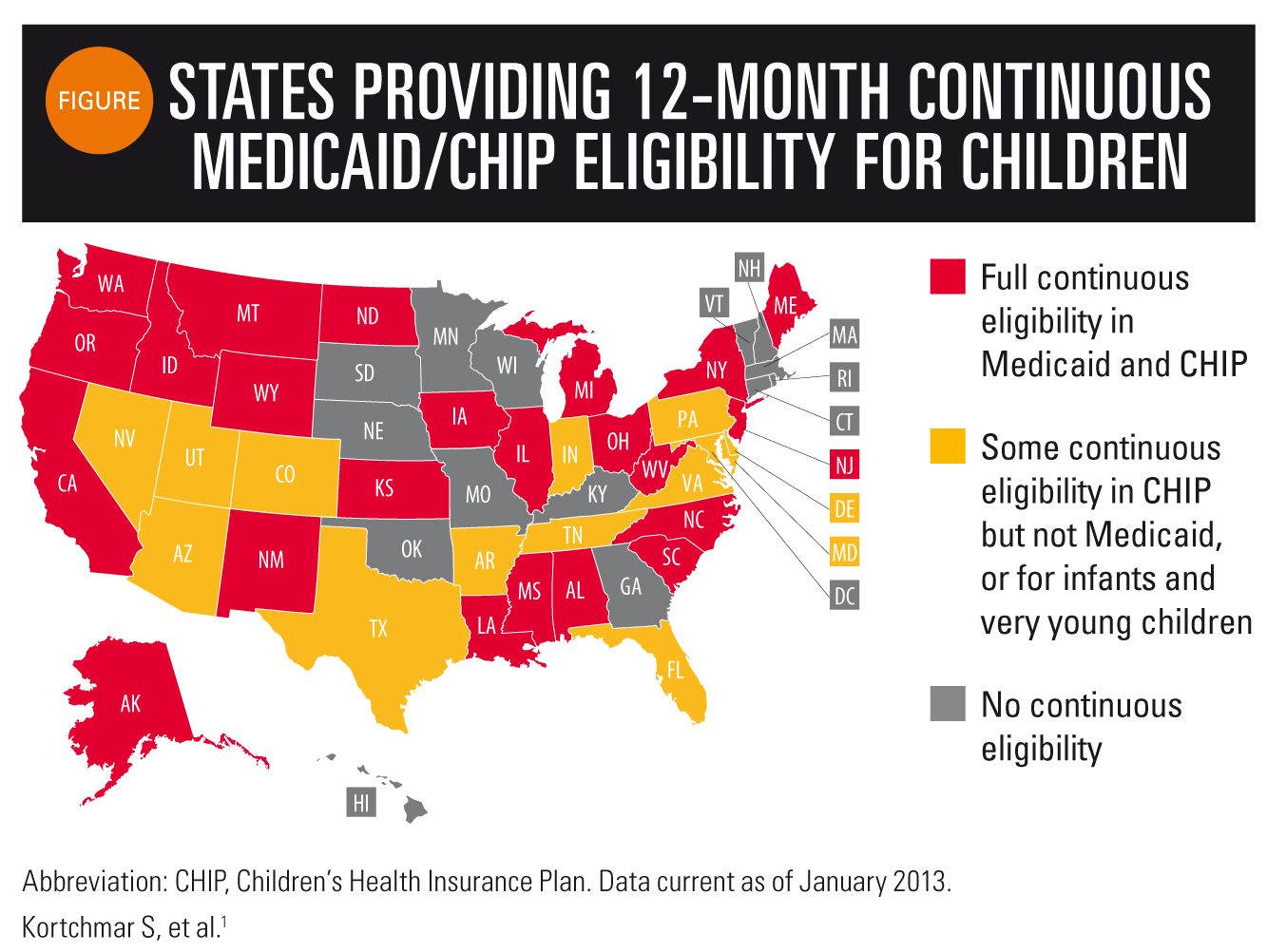

To address churn, 22 states have adopted 12-month continuous eligibility that allows children aged 0 to 18 years to maintain Medicaid or CHIP coverage for up to 1 year if family income changes (Figure)1: Alabama, California, Idaho, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, South Carolina, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

Brooks says this program is important for keeping children enrolled and putting states in a stronger position to measure the quality of care and health outcomes.

On February 3, 2014, US Senator Jay Rockefeller (D-WV) introduced to the Senate the Medicaid and CHIP Continuous Quality Act of 2014 that would require every state to adopt the 12-month program. According to his office, the bill would also provide performance bonuses to states for meeting criteria for enrollment and retention in the Medicaid program and make accurate reports on the quality of care provided by these programs, possible for the first time. His office could not be reached for comment on the next steps.

“Twelve-month continuous enrollment eases the administrative burden on healthcare providers and reduces the resources that health plans and state Medicaid programs must devote to processing new memberships or applications and verifying and reverifying eligibility,” says Murray.

Improving coverage

Thomas Long, MD, chairman of the Committee on Child Care Finance, AAP, is concerned that too few dollars are going to Medicaid although children represent more than half the US population. “All kids should be covered or we won’t have healthy adults,” he says.

Funding for CHIP, however, will run out in fiscal year 2015, even though the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will have authority over the program until 2019, as allowed by the ACA.

If funding ends, an AAP policy statement published in Pediatrics in January 2014 suggests that children meeting certain eligibility criteria would transition to the exchange with restricted access or lose insurance.

REFERENCES

1. Kortchmar S, Fellow E. Fact sheet: Continuous eligibility can prevent disruptions in health coverage for children. Washington, DC: Families USA; 2013.

State-level coverage pilot programs

New program in Washington State cuts churn

Washington State is tackling the problems of churn and discontinuity/disruption in family coverage through Apple Health Plus (AHP), a new program set to launch by July. Residents who are not eligible for Medicaid may now purchase qualified health plans (QHPs) through the state’s Health Benefit Exchange.

When these families experience changes in their incomes or family composition, they can also lose their eligibility for their QHP and become eligible for Medicaid, says Barbara Lantz, manager, quality and care management for the Washington State Health Care Authority (HCA) that oversees Medicaid managed care plans.

Apple Health Plus will allow family members who become eligible for Medicaid to remain with the same carrier and network providers as their other family members covered through the QHP, as long as the carrier is under contract with Washington’s HCA as a limited Medicaid managed care organization.

Lantz explains that the HCA will request monthly reports on those insured under the exchange to verify that a person has lost eligibility for their QHP and has become eligible for Medicaid. The new program will be limited to approximately 6,000 enrollees.

The AHP will also make it possible for carriers operating under the exchange to also offer coverage under Medicaid managed care.

Success in Louisiana

Facing more losses in covered lives than gains in the state’s Medicaid and CHIP programs in 2000, Louisiana took action to ensure that all eligible children were retained in the system.

There was a 22% to 25% monthly decrease in the Medicaid/CHIP population because they did not renew, says Diane Batts, Medicaid deputy director for the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals. Today, Batts says, only 1% or fewer of children’s cases are closed due to procedural reasons.

Louisiana has introduced a variety of initiatives to fix the problem of retention, including:

- Ex parte renewal. The state verifies continued eligibility through its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Louisiana Workforce Commission without having to contact the beneficiary.

- Discussing renewal when beneficiaries call for another reason.

- Requiring that staff make at least 3 attempts to contact beneficiaries before closing a case for procedural reasons.

- Telephone renewals in which the review of eligibility is completed without the need to submit a payer application.

In 2007, beneficiaries who were not likely to have changes resulting in closure could be automatically renewed if there were no real modifications in their financial situations. The program has reaped success by renewing 41% of beneficiaries, Batts says.

In 2009, Louisiana introduced the Express Lane Eligibility process, in which SNAP applicants share their information with the Medicaid agency and, if they are approved for SNAP, their information is shared with Medicaid for automatic enrollment without having to complete another application.

Ms Edlin is a freelance journalist and writer specializing in healthcare. She resides in Sonoma, California. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.