MOC reform: One year later

It’s been over a year since the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) announced its intentions to overhaul the maintenance of certification (MOC) process. In this reportorial article, Dr. Andrew Schuman brings you up-to-date with current MOC requirements and the changes likely to occur over the next year.

It's been over a year since the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) announced its intentions to overhaul the maintenance of certification (MOC) process. In this reportorial article, I'll bring you up-to-date with current MOC requirements and the changes likely to occur over the next year. In addition, I'll provide some updates regarding several developments that pertain to MOC opposition.

MOC circa 2016

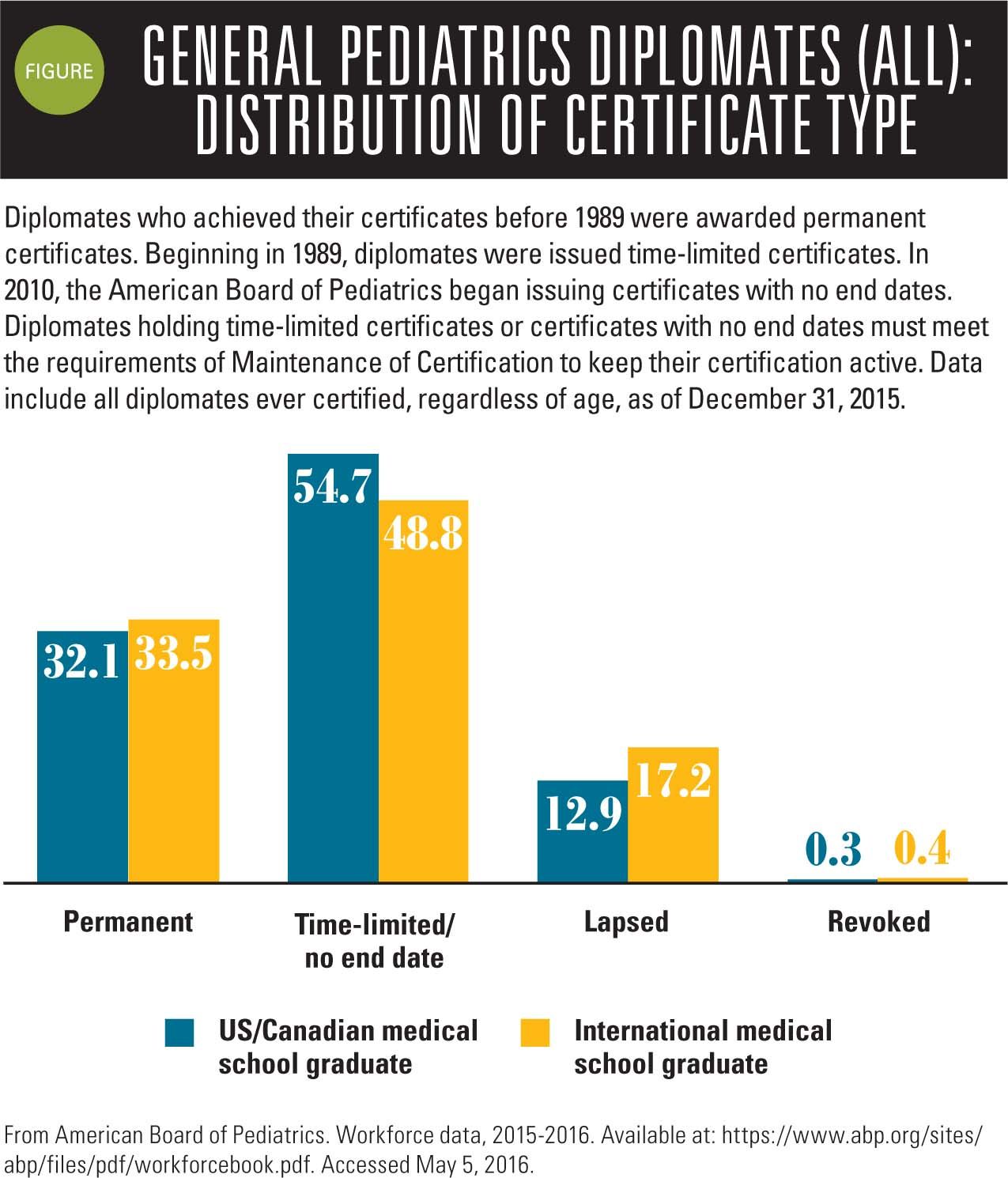

In 2010, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and its member boards changed the model of certification to today's model that is based on continuous "maintenance" of certification. As a consequence, in 2010, the ABP began issuing certificates with no end dates. Pediatricians were listed either as "participating in MOC" on the ABP website or "not participating in MOC." According to current data provided by the ABP website, as of December 2015, approximately 34% of the pediatrician workforce has a permanent certificate and 53% of pediatricians have time-limited certificates. These numbers are essentially unchanged from 2013. Of note is that about 14% of pediatricians have let their ABP certificates lapse, which represents a small increase from 11% in 2013 (Figure).

Related: 9 opinions on your professional societies

The situation that ultimately caused many of the member boards of the ABMS to consider a "gentler" approach to MOC involved a directive imposed on membership by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) in 2014. In that year, the ABIM mandated that member physicians participate in MOC every 2 years. Additionally, grandfathered ABIM physicians began to be listed as "certified, not meeting MOC requirements" on the ABIM website if they didn't register for continuous MOC.

In response to written protests from over 20,000 internists, the ABIM issued an "apology" letter that indicated that the ABIM would suspend several of its Part 4 requirements and change the language reporting a diplomate's MOC status on its website. The letter also indicated that the ABIM will update the MOC written exam to make it more relevant to current practice.

This event led to the development of an alternative board (more on this later) as well as the expectation among other physicians that their own boards would begin embracing "reform."

Changes in ABP MOC

Over the past year, the ABP began to solicit feedback from member pediatricians and expressed its intention to make MOC requirements less rigorous and more relevant to pediatric practice. The 2016 annual report from the ABP was recently published, and it includes much information regarding what transformations already have occurred and what is likely to happen to the 10-year recertification exam (MOC part 3).

Firstly, in response to discussions surrounding the quality assurance (QA) projects required for Part 4, the ABP now provides full 40 credits for pediatric practices that have achieved National Center for Quality Assurance (NCQA), patient-centered medical home (PCMH) status. Many practices have sought this certification, which I detailed in a previous Peds v2.0 article, "Home sweet 'medical home'" (Contemporary Pediatrics, November 2013). Achieving PCMH status assures patients (and insurance companies) that practices have met or surpassed quality benchmarks. This enables certified practices to prove eligibility for quality payment incentives offered by many Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and insurance companies. It should be noted however, that the ABP only provides MOC Part 4 credit for PCMH certification via NCQA, which is just one of several organizations that provide PCMH certification. These include URAC (formerly the Utilization Review Accreditation Commission), the Joint Commission, and the Accreditation Association for Ambulatory Health Care.

The ABP also provides MOC credit for participation in state or national quality initiatives. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics' (AAP) Division of Chapter Quality includes several ongoing quality projects involving asthma care, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnosis and management, immunizations, and mental health and adolescent substance abuse. Now MOC Part 4 credit is also granted for small practices that design and pursue their own QA projects, such as undertaking a project to improve rates of handwashing among providers and staff.

NEXT: A new exam format

A new exam format

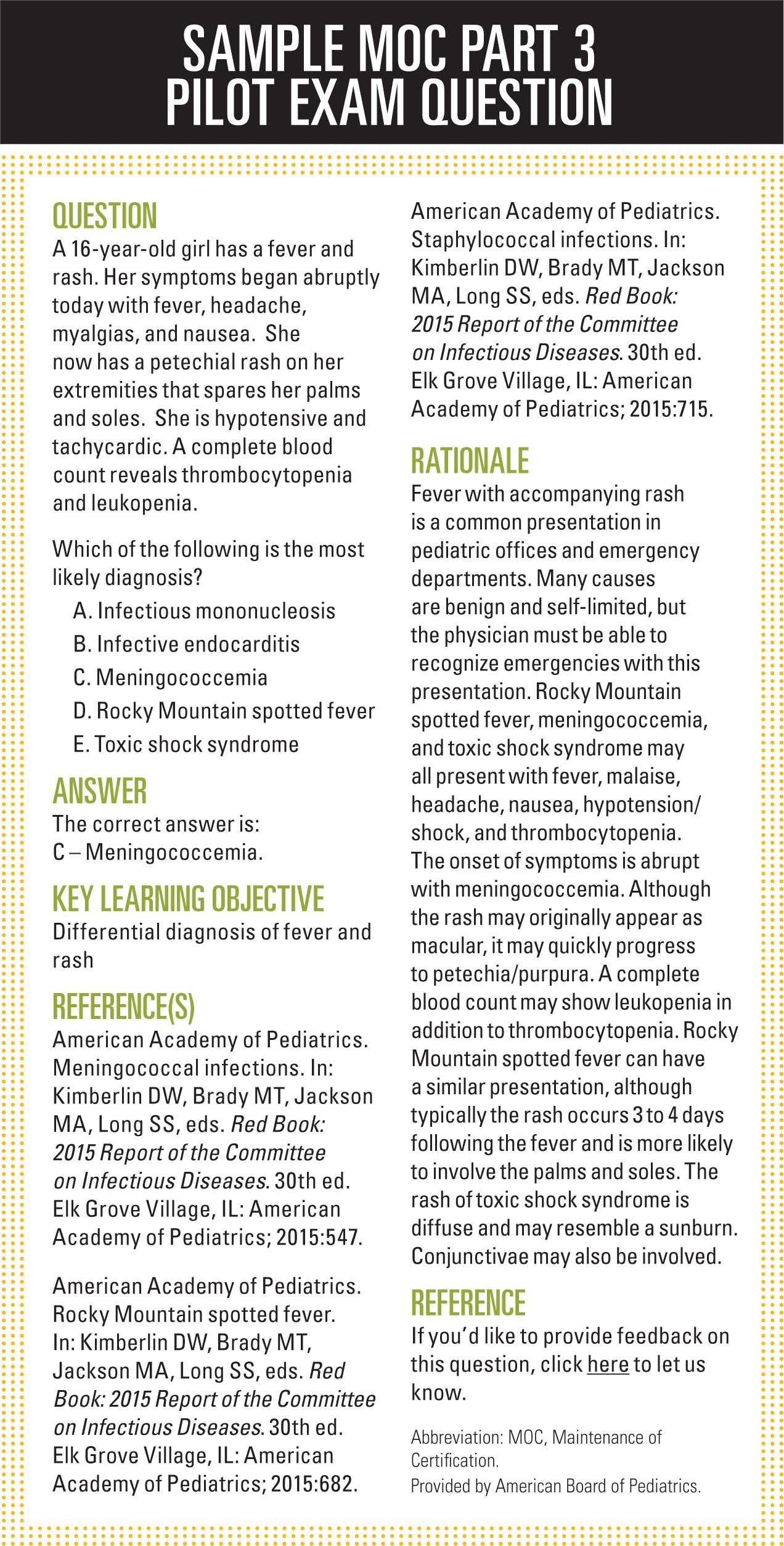

In May 2015, the ABP convened a conference to discuss converting the 10-year exam to one that is a complete departure from the existing format. The new testing concept is that pediatricians will be given questions on a regular ongoing basis, perhaps monthly via the Internet, and be allowed to research the topic before submitting their answers. In the view of the ABP, by changing to this format, pediatricians will utilize these questions either to gain new knowledge or reinforce present understanding. The idea was based on a pilot program developed by the American Board of Anesthesiology (ABA).

More: How to make pediatrics great!

In 2015, 1400 ABA members participated in a Maintenance of Certification Assessment (MOCA) pilot. Participants received 1 multiple choice question via e-mail once a week. Once accessed, they had a limited amount of time to answer. They received feedback immediately indicating whether the answer was correct and a brief discussion, including references. If answered incorrectly, they would receive follow-up questions on the same subject weeks or months later. The ABA has subsequently replaced its current system with a redesigned MOCA 2.0 program that went into effect in January of this year.

According to a recent blog posted by ABP President and CEO David G Nichols, MD, provisional features of the ABP version of the MOCA exam will include the following (subject to change):

- Diplomates will establish a practice profile when registering for MOCA, so that the content can be weighted to suit the type of practice.

- Diplomates may receive 1 to 3 multiple choice questions per week.

- The amount of time allowed for the answer may vary depending on the complexity of the question.

- Online resources or books may be used, but because each question is timed, the diplomate will need to judge carefully whether to invest time in searching through a resource.

- A feedback page will pop up after submitting the answer.

- A randomization protocol will minimize the likelihood that any 2 diplomates receive the same questions during a given time period.

- Flexibility will allow diplomates to decide when to respond based on their schedule and time availability. Test security provisions may vary depending on whether the diplomate chooses to answer questions during the week they are delivered or wait to answer a batch of questions.

- If MOCA is ultimately adopted, the ABP will make pass/fail decisions based on the response patterns. Those who successfully participate will meet standards for Part 3 of Maintenance of Certification.

An ABP MOCA pilot will be launched next year. Interested pediatricians should visit the ABP website (www.abp.org) to find out more about the program and consider participating in focus groups regarding the MOCA pilot.

NEXT: Sample MOC Part 3 pilot exam question

NEXT: First anti-MOC laws

More nays

There are many physicians opposed to the MOC certification.

Cardiologist Paul Teirstein, MD, has started an alternative board of medical specialties called the National Board of Physicians and Surgeons (NBPAS) and is encouraging interested physicians to promote this alternative board to hospitals and insurance companies as well as to other physicians. The NBPAS requires previous board certification and participation in yearly continuing medical education, and membership costs only $169 every 2 years. As of this writing, the NBPAS has enrolled over 3000 members and is accepted by 26 hospitals nationwide.

Next: Communicating in the high-tech office

Many pediatricians continue to express their opposition to MOC. Interested pediatricians should view the many anti-MOC blogs available on the Rebel.MD website. Last year, several pediatricians developed the Peds4MOCreform.org website to express their opposition to MOC. So far their site has garnered more than 6500 signatures supporting MOC reform.

The first anti-MOC laws

The state legislature of Oklahoma unanimously passed a law that went into effect on April 12, 2016, making it illegal for medical facilities to make MOC a requirement for medical practice.

The law states: "Nothing in the Oklahoma Allopathic Medical and Surgical Licensure and Supervision Act shall be construed to require a physician to secure a Maintenance of Certification (MOC) as a condition of licensure, reimbursement, employment, or admitting privileges at a hospital in this state."

Other states such as Michigan and Missouri have similar laws currently under consideration. In addition, in early April, Kentucky governor Matt Bevin signed SB17 into law. This bill is the first state law to be passed and signed that makes it illegal to require specialty medical board certification or MOC as a requirement for practicing medicine in the state.

There are also 19 state medical societies that have officially expressed opposition to MOC. These are California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin.

To be continued

This concludes my brief reportorial update on MOC reform and opposition. Just because I have not expressed my opinion does not mean that you should not express yours. Has the ABP done enough, or should it do more? Please contact the editors of Contemporary Pediatrics to tell them what you think of these ABP MOC changes.

Dr Schuman, section editor for Peds v2.0, is adjunct assistant professor of pediatrics, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and editorial advisory board member of Contemporary Pediatrics. He has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.

Anger hurts your team’s performance and health, and yours too

October 25th 2024Anger in health care affects both patients and professionals with rising violence and negative health outcomes, but understanding its triggers and applying de-escalation techniques can help manage this pervasive issue.