Our 1st Issues and Attitudes Survey: 5 ways your practice will change and the 1 way it won't

Buffeted by a perfect storm of regulatory, fiscal, and technology factors, many pediatricians are voting with their feet.

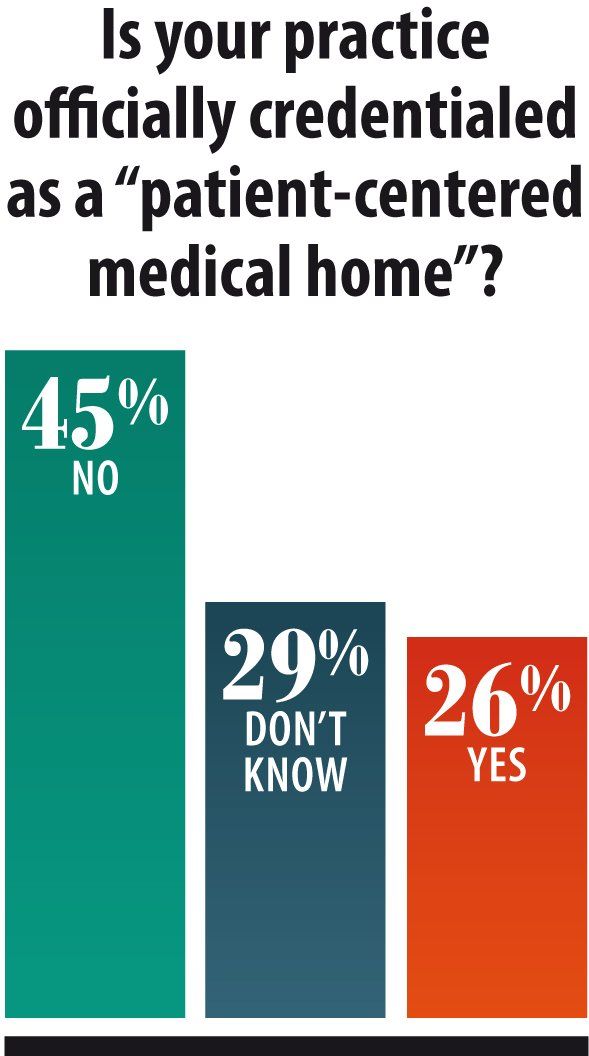

In Contemporary Pediatrics’ first annual Issues and Attitudes Survey, we asked you to candidly speak your mind-and you did so in spades. From the tighter pinch of reimbursement, to the sustained stressor of the unknowns surrounding the rollout of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), what emerged is a picture of dedicated practitioners stretched thin-and making some changes as a result.

What we did

The nearly 50-question confidential survey was fielded from November 7 through November 19, 2013, to a population of over 32,000 US-based pediatricians.

Who responded

Over 68% of the respondents were office-based pediatricians in private practice. The remaining approximately 30% were divided fairly evenly among pediatricians in hospital, academia, and “other” work settings. Slightly over half serve suburban communities, with 33% and 16% serving urban and rural communities, respectively. Participants were skewed slightly female by 9%, and had an average age of 52 years with an average of 17 years in practice. Eighty-eight percent indicated general pediatrics as their specialty, with adolescent medicine, neonatal-perinatal, family practice, pediatric allergy and immunology, and other specialties rounding out the remainder.

What we found

The very factors that caused you to pick pediatrics in the first place are being eroded by a perfect storm of regulatory, fiscal, and technology factors.

While “average salary earned by attending physicians in the specialty” ranked only an average of 2.3 on a scale of 1 to 5 in importance among the factors that survey respondents considered in selecting pediatrics as a specialty, survey comments reflect that pediatricians’ even modest payment expectations are being challenged by a chaotic “new normal.”

“Compensation has not increased for over 10 years,” noted one commenter. Another concurs: “My income has consistently gone down, although my work load has gone up.” Yet another elaborates that the problem is not the stagnant or shrinking compensation alone, but that factor in combination with burgeoning service expectations: “Pediatrics remains one of the lowest compensated specialties despite increasing demands to handle increasingly complex patients.”

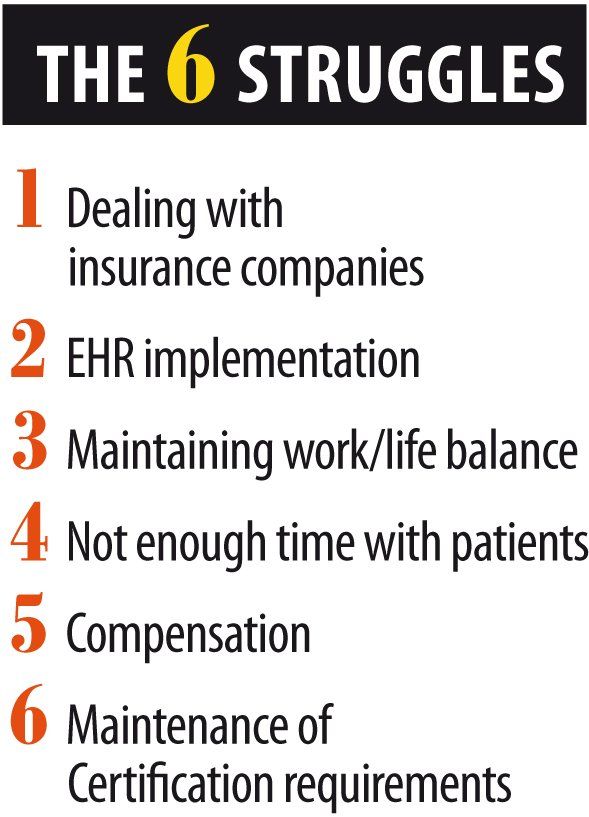

Many participants voiced the particular plight of the private practitioner caught between bureaucracies: “We need better reimbursement and less red tape from insurance companies and the government.” Another lamented: “I have become disillusioned with medicine. Our leaders have compromised themselves to the politics of medicine instead of fighting for what is right for the patients and their families.” Overall, 42% of those responding characterized their current satisfaction with their job situation as either “very” or “somewhat dissatisfied.” Only 14% expressed extreme satisfaction.

The whimper of our discontent

The hydra of unhappiness has many heads. One oft-repeated sentiment expresses a generalized feeling of powerlessness against the forces most impacting pediatricians’ daily lives. “Over the last 20 years, physicians have given up more and more control,” wrote one pediatrician. “Quality care is falling tremendously due to all the extrinsic factors; I see nobody really pushing to support care of children by giving real value to pediatrics,” stated another. Still another put it this way: “I feel care [is being] dictated without practical considerations in mind.” Others voiced frustration at their sense that pediatrics is becoming the Rodney Dangerfield of medical disciplines: “Pediatricians are the lowest ranked, lowest paid, and have the least respect of any of the medical specialties,” one commenter summarized.

Yet others think that the encroachment of physician extenders is one element of the “dissing” of the discipline: “More needs to be done to protect the work that pediatricians do. It seems everyone feels [nurse practitioners] can do our job.” Still others worry not just about the pediatrician’s lot, but, characteristically, about how their young patients will fare in the hands of others: “We continue to see increases in unqualified Minute Clinics attempting to care for children and leaving the mess for us to clear up. Little [has been done] to lobby for quality of care for pediatric patients.”

#1: You’ll consider going part time or becoming an employee

A reaction for every action isn’t mere physics

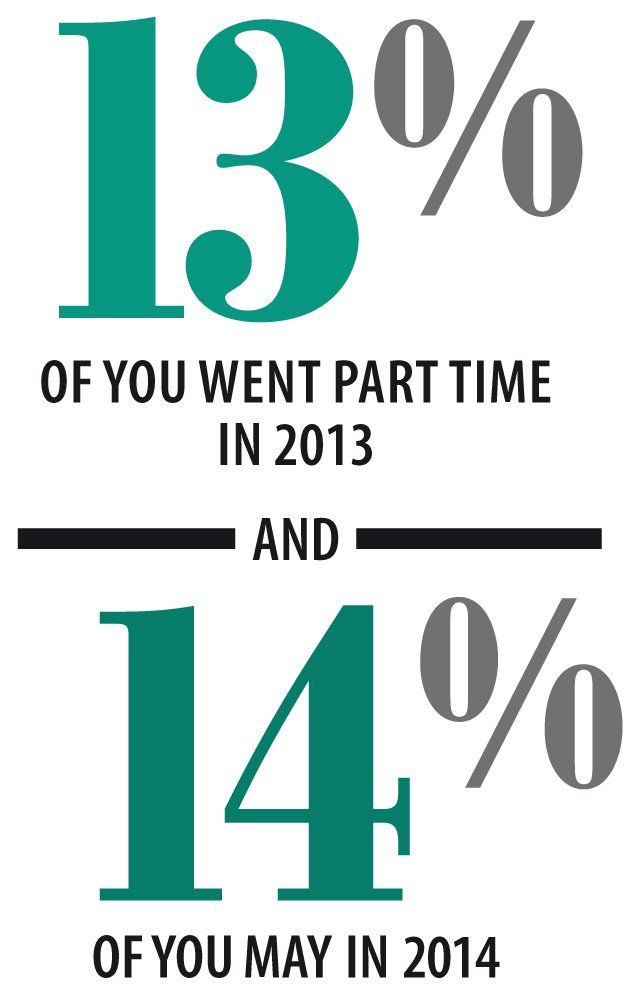

Perhaps the most dramatic response to the increased pressure has been the number of pediatricians who have elected to reduce hours to counter the stress-or who are considering doing so.

In this year alone, 13% of survey respondents elected to go from working full time (defined as 40 or more hours per week) to part-time status; another 14% say they are considering that move in 2014. The most often-cited reason for the move to part time was an effort to seek a “better life-work balance” (47%). This squares with the ranking in importance that participants gave to the 21 factors that they considered when choosing pediatrics as a specialty in the first place: “Having a balance between work life and personal life” clocked in as the fourth highest factor cited of the 21, behind only job satisfaction, having an enjoyable work day, and the collegiality of coworkers.

Interestingly, despite some expressions of an insufficient appreciation of the profession by the world at large (“[There is] not enough being done to educate the public about the value of pediatricians”), “perceived prestige of the field” was still held as a minor value overall, coming in as the third-lowest-ranked of the 21 factors that drove the election of pediatrics as a calling.

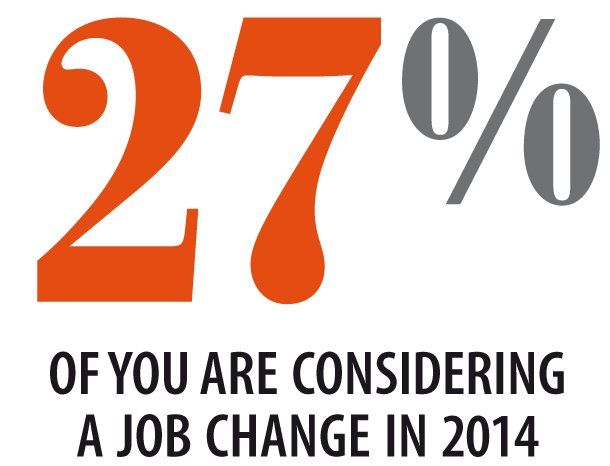

A different but related reaction to the heaving health care landscape is to depart the entrepreneurial arena-and you and your colleagues are mulling it over. When asked if they were considering leaving their own private practice to become an employee of a hospital or other organization in the next 12 months, 11% of those surveyed responded in the affirmative. Forty-eight percent of those answering yes specifically selected “current health care environment not conducive to entrepreneurs” as their reason. The recurring theme of “better work-life balance” was cited as the basis for 22%, and for 8% of respondents, the departure was being considered in a bid to reduce workweek hours to part time. Only 6% stated that the consideration was being made in order to seek a “better professional opportunity.”

#2: You’re likely getting an EHR-or replacing one

The double-edged tech sword

Repeatedly, the survey revealed technology to be both a boon and a bogeyman. Its value corresponded to the degree to which it had been effectively and efficiently integrated into the daily workflow and the perceived efficiency it brought to practice processes.

Even for the minority of those who responded that they felt more optimistic about their ability to adequately provide care for their patients in 2014 than in the current year, only 22% attributed that optimism to the “availability and integration of technology tools in the practice.” Even fewer (8%) specifically credited their glass-half-full spirit to the implementation of an electronic health record (EHR) in the practice. In fact, 43% called out “ineffective or burdensome technology” as a key reason why their stress level at work had increased within the past 12 months. Only 18% said that the addition of technology support had improved their lot by diminishing their stress level in their workplace.

The EHR do-over

Some of the disgruntlement may be in reaction to the Groundhog Day-like experience many practices are reliving in the implementation of version 2.0 of their EHR systems-having to repeat the downtime and staff training investments necessary to migrate to a new system when the first was found wanting either in functionality, realized workflow efficiencies, or both.

“No voice can be heard about the problems with EHRs,” stated one respondent. Lack of systems’ seamless data exchange was the locus of this commenter’s 3-exclamation-marked irritation: “EHRs are the work of the devil . . . . Make them communicate with each other and make them efficient. Mandate this!!!” Still another laid the dearth of discipline-specific EHRs directly at the feet of his professional pediatric society for “not having an EHR for all pediatricians.”

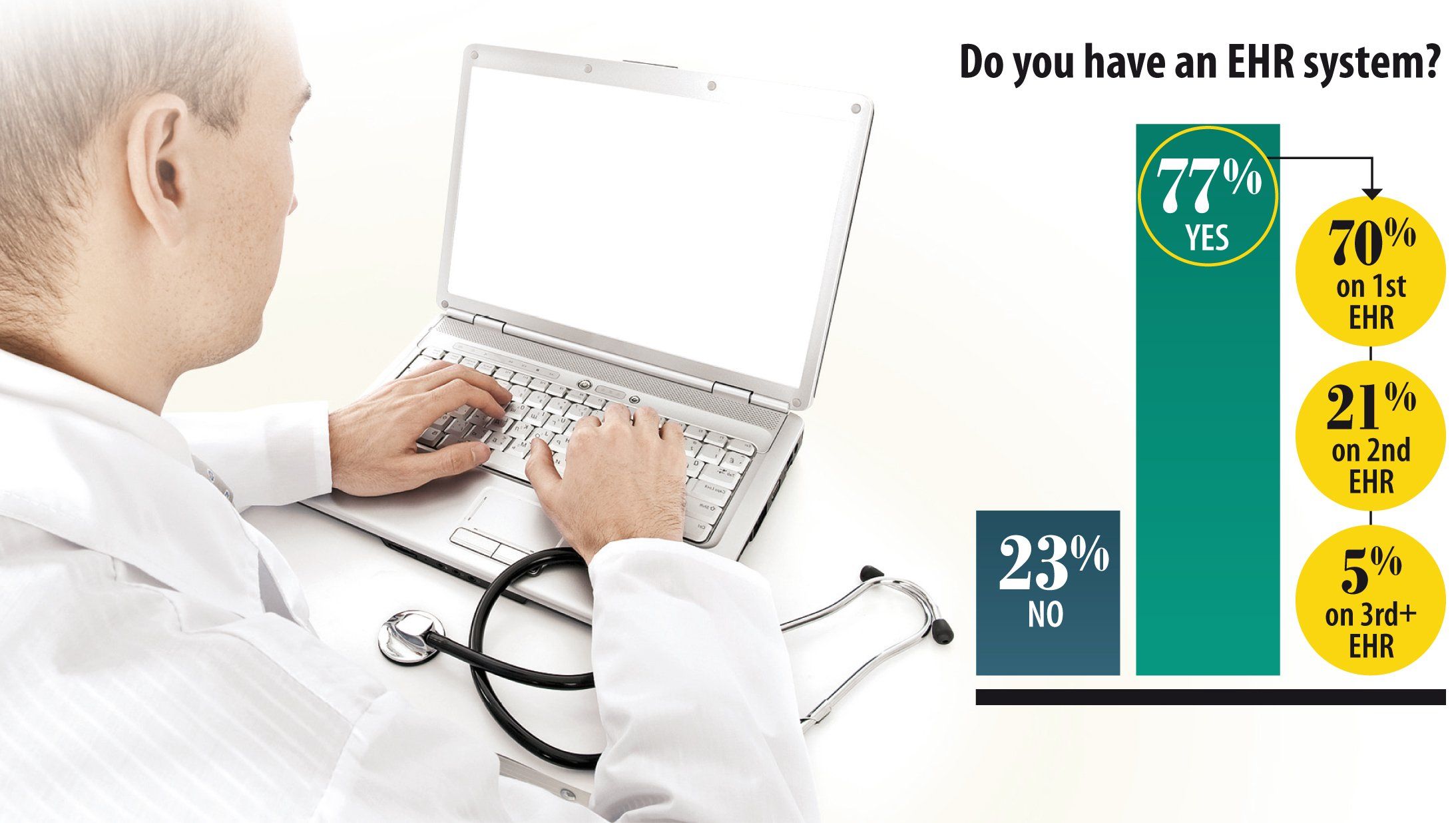

Whether the responsibility for the technology glitches lies with the dark deity or one of the pediatric fraternities, the impact-and often the churning-of EHR systems was evident in our survey findings. Of the 77% of practices that currently have an EHR system in place, 21% are on their second system, with 5% on their third or more. For some, the EHR challenge is in future tense; as late as the Q4 2013 fielding of the survey, nearly a quarter of respondents stated that their practice still had no EHR system in place at all, despite dangled federal carrots and impending sticks.

#3: Your administrative paperwork burden will (continue to) burgeon-despite #2

The paperless practice myth

The contradiction of the growing demands of administrative tasks on their workday despite technology’s ubiquity was not lost on those responding to the survey. “Bureaucracy and paperwork are increasing,” states one commenter flatly. Another added to the paper-chased chorus: “Little has been done to help the average office-based pediatrician to survive and prosper in this era of lower reimbursement, increasing administrative work, and third-party oversight.”

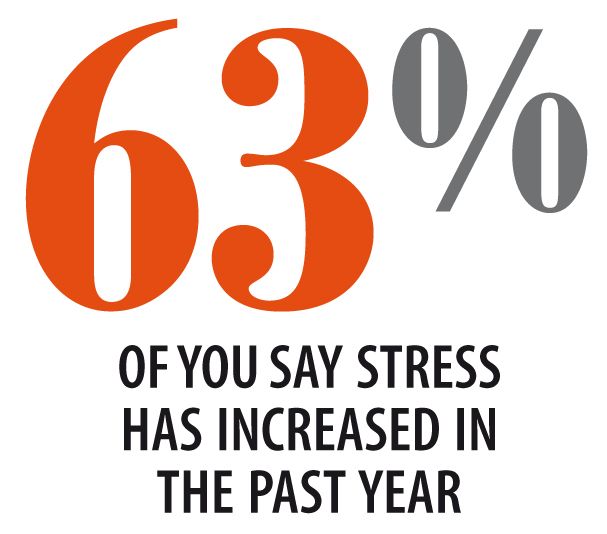

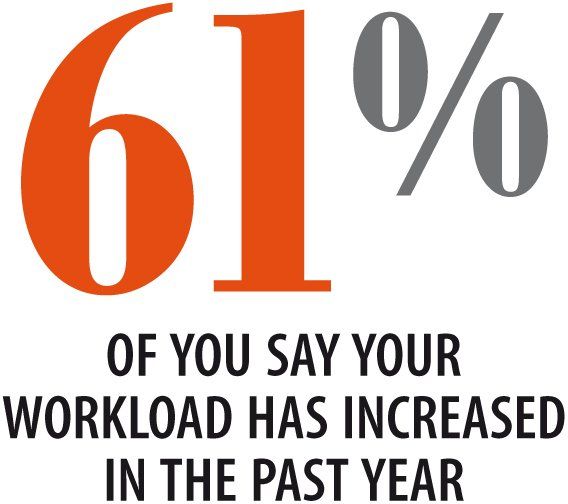

In fact, increased administrative work outstripped any other single factor as adding to pediatricians’ stress levels, cited as the penultimate pain point by 61% of survey respondents. The related nettle of “inefficient workflow processes” also ranked a formidable 38% as a workplace-stress contributor.

Exacerbating the problem is the sense that the administrative onslaught is coming from all sides. As one survey respondent put it: “I can't write how I feel about the red tape nonsense . . . red tape from insurance companies, red tape from my academy, red tape from admin, etc . . . . Who is fighting for us while we are swamped in the trenches?” Another echoed: “We need less red tape and better reimbursement from insurance companies and the government!”

#4: You’ll wrestle with MOC

Whose side are you on anyway?

One development that doesn’t appear to be sitting well with those already chafing at mounting paperwork and administrative demands on their time is the Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirement being implemented by the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP). Twenty-one percent of survey respondents chose MOC requirements as one of the top challenges to their effective practice as a pediatrician in 2013.

As one pediatrician summarized: “The requirements are becoming more stringent for obtaining MOC credit, especially for Part 4, and for many pediatricians, the current options for Part 4 MOC credit are: 1) expensive; 2) time consuming-need to be performed outside of patient care hours; and 3) not easily applicable to practice, or at least it is hard for them to discern the benefit to their practice.”

It seems clear that, for some, the MOC requirements hit at a cherished value that initially spurred their selection of pediatrics as a vocation as mentioned earlier: the elusive work-life balance. “Further, adding MOC requirements only increases our stress and makes finding a work-life balance that much harder,” wrote one respondent. “I want less administrative nonsense, not more busy work!” exclaimed another. Others were more blunt: “MOC is a complete waste of time"; “the MOC is overwhelming and impractical"; and “don't even get me started on how ridiculous that all is!”

Also evident in the survey comments was a sense of disconnect between the programs’ requisite time investment and the perception of its direct benefit to patient outcomes. “[There is] no proof these policies improve care for patients and make me a better physician,” one pediatrician held. Another commenter believes that a second look should be taken at the MOC program entirely in light of pediatricians’ day-to-day press: “Continued recertification, MOC requirements, and exam taking, when there is limited time given patient loads, should be reassessed.”

#5: You fear you won’t be able to provide the same level of care you did in 2013

Who’ll look out for the kids?

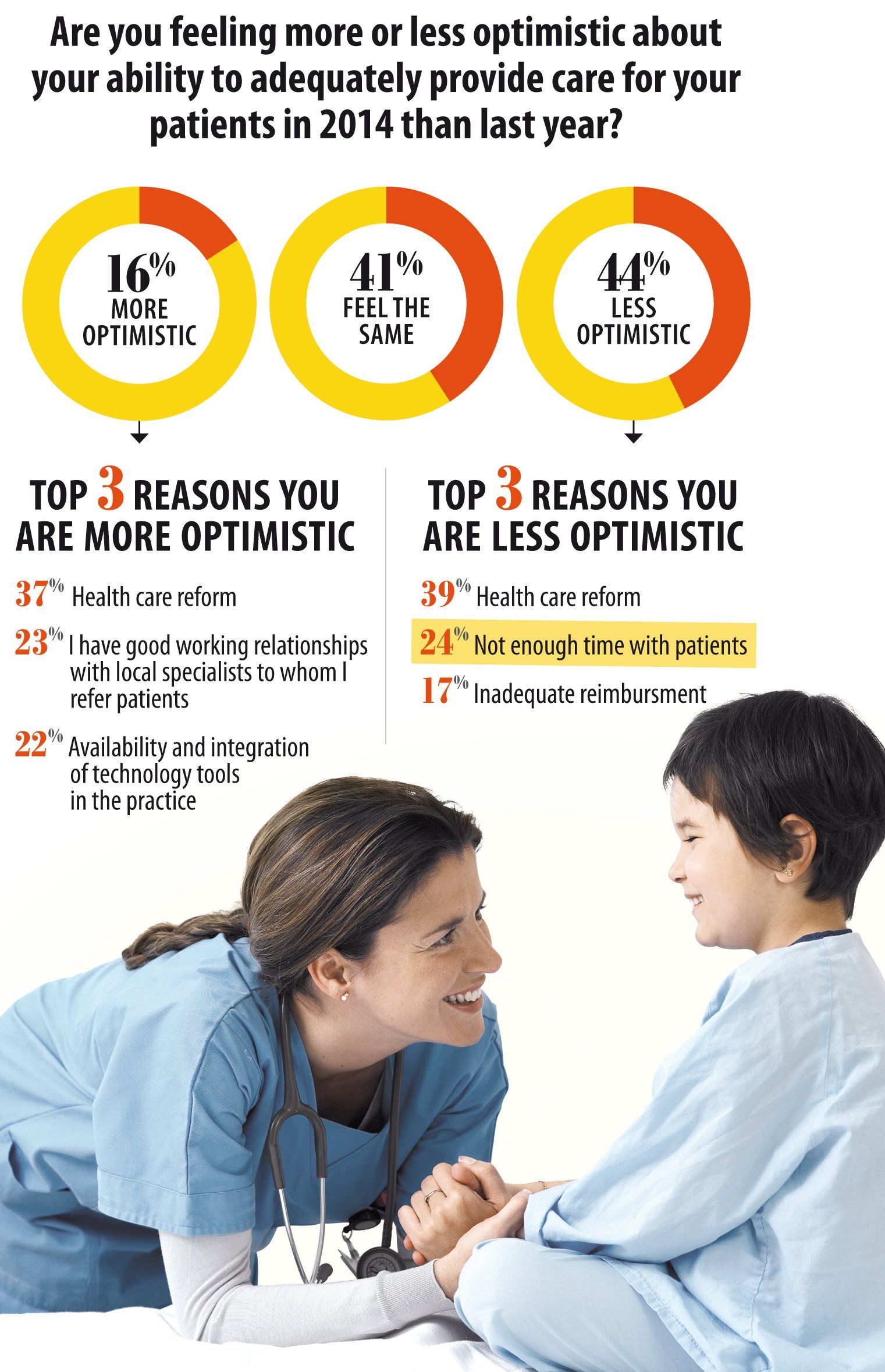

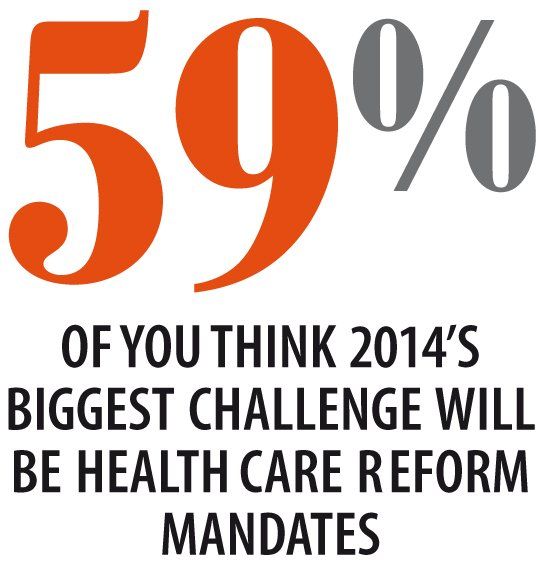

When asked, 44% of those surveyed admit to being less optimistic about their ability to adequately provide care for their patients in 2014 than this year. Whereas health care reform was given as the primary reason for their darker view (39%), insufficient time with patients (24%) and inadequate reimbursement (17%) were also top mentions.

Still others point to more subtle corrosions to their ability to sustain care at this year’s levels, such as “inadequate community support systems” for their patients and their families (6%), their observation that they are “seeing more children at risk than previously” (5%), and that they believe they are “losing my patients to the popular culture” and “it is increasingly difficult to communicate with the parents of my patients”-both cited by 3% of respondents, respectively.

Success in any language

Despite the gloom, there were some positive signs that emerged from the survey. For example, when asked to characterize the degree to which language and medical literacy stood as barriers to effective patient care, only 14% of respondents perceived these as major impediments growing in severity. Fully 55% saw them as difficult barriers, but ones that were being actively addressed with some success. Others fully scored this in the “win” column, with over 30% of responding practices having “put training and resources in place so that this is no longer a barrier to care.”

Glass half full

There were additional factors that mitigated some respondents’ concerns about the future. Of pediatricians who said they were more optimistic about their ability to

adequately provide care for their patients in 2014 than in this past year, ironically, 37% cited health care reform as their primary reason. Twenty-three percent attributed their optimism to having a strong network in place: “I have good working relationships with local specialists to whom I refer patients.” Another 22% cited the availability and integration of technology tools in their practices as a basis for their positive view of the year ahead.

And the 1 way it won’t!

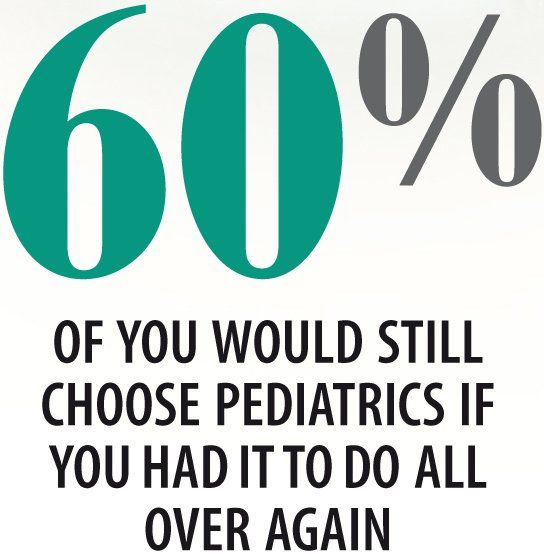

Excuse me, but your love of kids is showing

The apparent constant in the equation of the year to come is that you’ll still want to be caring for kids. Overwhelmingly, the survey shows, despite the year’s travails, if you had it to do over again, over 60% of you would still choose to go into pediatrics over any other medical specialty (although, candidly, dermatology made an interesting showing at 14%!).

In fact, the instances in the survey in which organizations are cited with admiration are invariably mentioned in the context of their efforts or progress toward better care for children. Three percent of respondents point to effective health care education programs in local school districts as a reason to be optimistic about the year ahead, for example. “More local organizations are working hard at . . . improving patient care,” commented one respondent. Another gives kudos to his professional society for being “out front on health policy and social issues that affect children.” Props go to societies, too, from one commenter who “appreciates political activity for the benefit of children”; from another for recognizing societies for being “good advocates for children, not just the MD”; and from a third who thinks his association is “working hard to ensure the best care for children.” Yet one more praises his state medical society for being “exactly what I need for advocacy.”

Even the points of dissatisfaction expressed correlate to the degree to which your treasured doctor-patient interactions are being impeded. Twenty-four percent cited “not enough time with my patients” as a primary concern that informed their pessimism about their future ability to serve their young patients as well as they have in the past. Indeed, a full 30% cited this lack of patient face time as among the top challenges they confronted in 2013. Still, in the end, even in the face of the finding that 61% of you who responded to the survey stated that your workload has increased in the past year, on a 1-to-5 scale of the factors upon which you chose the pediatric specialty, “Having a low-stress work day,” after all, ranked a paltry 2.

In a recent conversation about the convulsions of health care reform and its particular impact on Medicaid, one 30-year general surgeon acquaintance remarked that, “Pediatricians are the single-most altruistic of any of the medical specialties, bar none.” Without a doubt. But, especially given the turmoil of the passing year, it’s hard not to also think of Winston Churchill’s assertion: “We have not journeyed all this way because we are made of sugar candy.”

MS MCNULTY is content channel director for Contemporary Pediatrics and has worked in physician-directed health care publications for 14 years. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.