Preventive health care in the high-tech practice

Office-based technologies help to make preventive care visits more efficient.

One of the most important things we do as pediatricians is to attempt to improve the quality of children’s health via preventive health care visits. In this article, we’ll review the current American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care (RPPHC) and discuss how we can best use technology to ensure that our patients are as healthy as possible.

Kids have “Bright Futures”

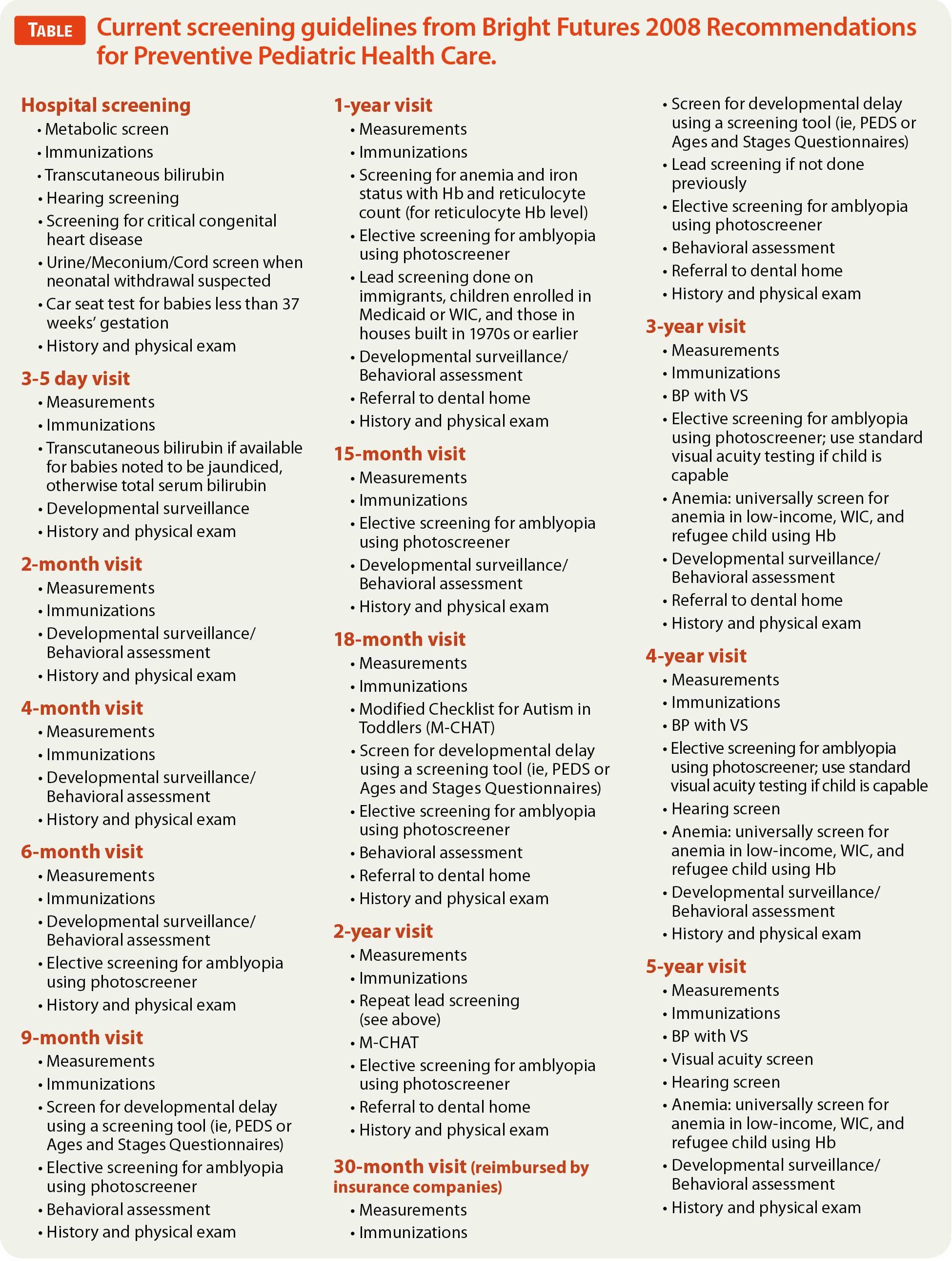

The Bright Futures initiative was launched in 1990 under the leadership of the Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) of the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). In 2001, the MCHB awarded cooperative agreements to the AAP to lead the Bright Futures initiative. The linchpin of Bright Futures is the RPPHC, a wide-ranging set of guidelines that represent a single standard of care for pediatric providers. Bright Futures and the AAP continually update these recommendations, also called the periodicity schedule, which guide pediatricians and parents as to when well visits should be performed and which screening tests should be done at each visit. Because the periodicity schedule was last updated in 2008, there are new recommendations that have yet to be integrated into the periodicity schedule. For example, there are new recommendations regarding screening newborns for critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) before discharge from the hospital and screening young children for iron deficiency at 1 year of age.1,2 There are also modifications to previous recommendations for screening pediatric patients for hyperlipidemia as well as an endorsement of photoscreeners to electively screen for amblyopia in children.3,4 The Table lists screening guidelines that are current as of this writing.5

Putting preventive health care into practice

There is no question that pediatric medicine does an extremely good job of identifying significant medical problems in newborns so that corrective measures can be implemented. All babies are screened in the hospital for metabolic diseases, hyperbilirubinemia, hearing deficits, and CCHD. In addition, those newborns at risk for neonatal withdrawal syndrome may have their urine, meconium, or cord tissue screened for drugs. Some premature babies may have screening head ultrasounds, retina exams, and car seat tests prior to discharge. Following discharge from the newborn nursery, babies are seen a few days after birth to monitor for jaundice and adequacy of feeding. Babies born prematurely or those with complex medical problems have timely follow-up with necessary pediatric specialists, and those who are born via breech presentation or otherwise at risk will have a screening hip ultrasound at 6 weeks of age. Despite our many screening successes, there is clearly much room for improvement. Pediatricians are currently challenged with “new morbidities” that include obesity and developmental problems, as well as high-risk behaviors among teenagers that can be associated with sexually transmitted diseases, substance abuse, and depression.

Much needs to be accomplished in a preventive health care visit, which typically is allotted only 20 minutes on a pediatrician’s schedule. Fortunately, many high-tech tools are available to facilitate this process and make it possible to make use of time before and after the routine office well-child visit to screen for problems and educate parents regarding important health care issues.

Getting them in the door

Even the most well-meaning parents need to be reminded to attend their scheduled office visits and to make appointments for health maintenance visits. While your staff may be expert at placing reminder calls, this is a chore that is best assigned to a growing number of “reminder services” that are affordable and effective at getting patients in the door. Practices merely transmit a copy of your schedule and patient demographics to the reminder service via the Internet and they take care of the rest. Automated phone call reminders continue to be effective, but reminder services often get the best results by using software to send text messages or e-mails. If your electronic health record (EHR) can generate a list of patients overdue for their well-child visits, these services can also make sure parents are reminded to make appointments for these as well.

Using patient portals

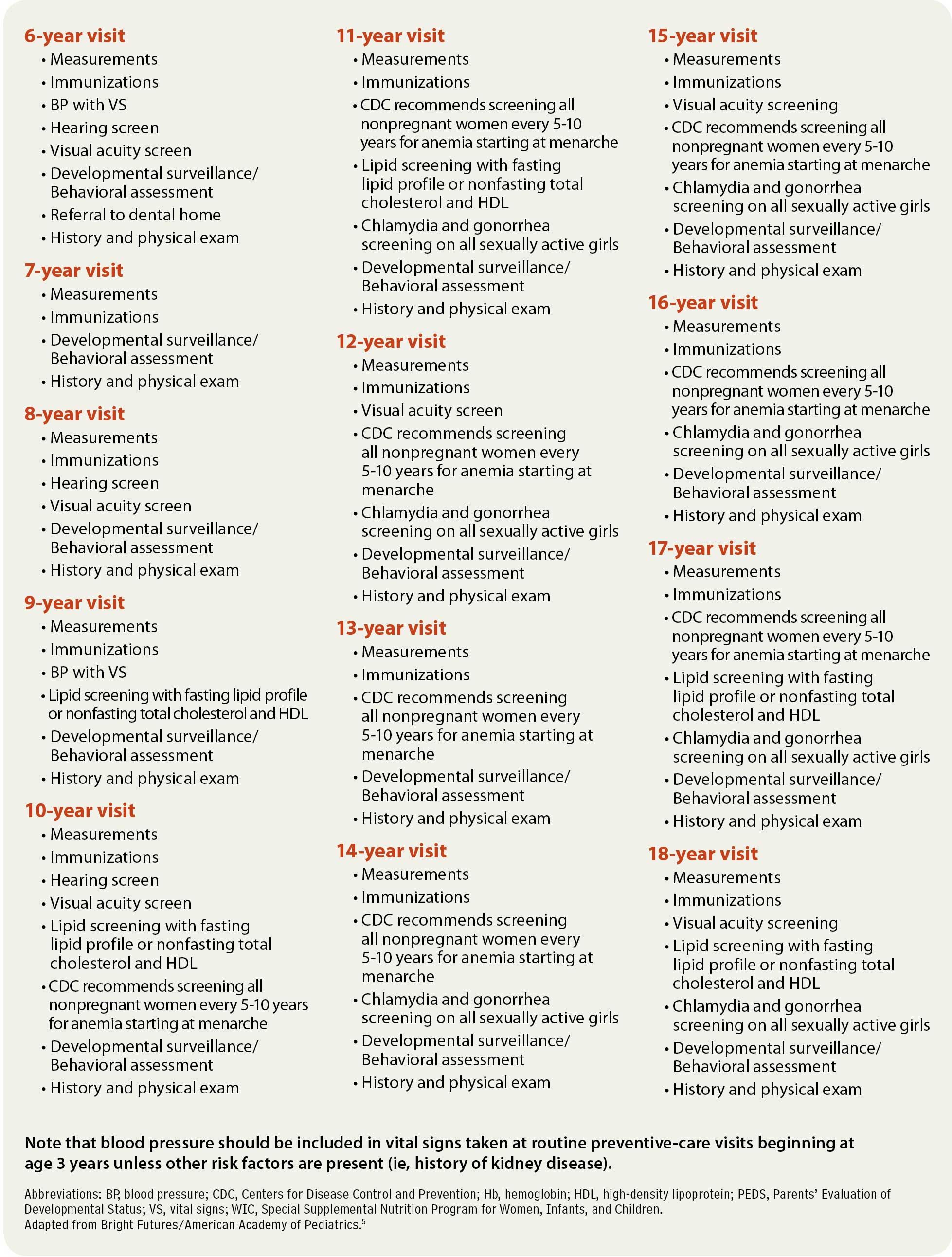

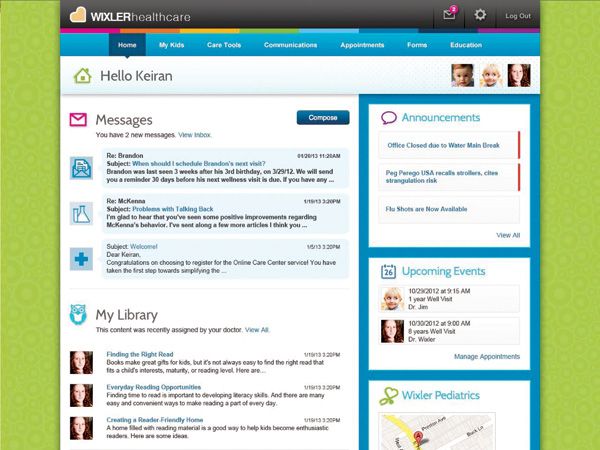

If you have invested in a full-featured (meaning expensive) EHR, chances are you also have a Web portal to facilitate communication with patients. Web portals allow secure communication with patients’ parents to schedule office visits, collect payments, refill prescriptions, and provide educational materials for review. I recently became aware of a novel new pediatric office portal that does not require purchase of an EHR. The product is konciergeMD.com (konciergeMD; Newton Square, Pennsylvania), which features a customized practice Web portal and mobile applications that provide all the features mentioned above and then some. Because it is pediatric oriented, it prepares parents for office visits by advising them which immunizations will be administered, lists

konciergeMD.com: Features customized Web portals for communicatng with patients.age-appropriate milestones, and helps parents organize their questions so they can make optimal use of their limited time with the pediatrician. From the pediatrician’s perspective, konciergeMD.com will work with practices to extract data from their EHRs to facilitate communication with patients. Lists of medications are maintained on the site, as are current immunization reports. The pricing model is very interesting because the company charges a reasonable per-physician yearly fee, or, alternatively, parents can “subscribe” to the practice portal for a $10-per-month fee that provides access to “premium features” designated by the practice, such as the ability to correspond with their physician or obtain forms electronically.

Efficient use of time

Previous installments of Pediatrics V2.0 have discussed optimizing practice efficiency and reducing dependency on traditional paper forms. Once a parent checks in at the reception window and demographic and insurance information are confirmed, the parent is given a visit questionnaire to complete via clipboard or tablet. If your practice has already upgraded to V2.0 status, then the parents would have completed a visit questionnaire available on the practice Web site or e-mailed to them in advance of the visit. As I suggested in prior articles, if your practice uses the Child Health and Development Interactive System (CHADIS; Total Child Health; Baltimore, Maryland) online service, the parent would have completed the age-appropriate questionnaire and screening tools in advance of the visit. At the time of the visit itself, the CHADIS documentation is recalled electronically and results pasted into your EHR well-visit note after they are reviewed with the parent.

Expediting vital signs

Welch Allyn (Skaneateles Falls, New York) has been a pioneer of office technology for a very long time. Over the past few years, the company has developed devices that facilitate obtaining patients’ vital signs and transmit results wirelessly to dozens of popular EHRs. This obviates the need for nurses to manually input the vital signs every time a patient is roomed. Its Connex Integrated Wall System combines an adult and/or

Connex Integrated Wall System: Facilitates taking vital signs and transmits data to the EHR.pediatric sphygmomanometer that rapidly records blood pressure and pulse rate with a pulse oximeter, as well as an ear or digital thermometer, with its standard LED macroview otoscope and ophthalmoscope. The system also integrates with a number of adult and pediatric scales.

Point-of-care testing

When nurses prep a patient for a preventive care visit, they can perform point-of-care testing that can provide physician and parent with a patient’s lead levels, transcutaneous bilirubinometry, lipid levels, and hemoglobin when indicated. Investing in other technology such as otoacoustic emissions (OAE) hearing screeners and photoscreeners can speed screening at well visits. I recommend that in areas where children are at risk for lead poisoning, practices consider purchasing the $2,500 LeadCare II Analyzer (Magellan Diagnostics; North Billerica, Massachusetts), which enables practices to screen for lead poisoning by testing either finger stick or venous specimens. As you know, children at high risk for lead poisoning are those in Medicaid, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), immigrants, or those occupying or frequently visiting housing built in the 1970s or earlier. Lead screening is typically performed at 12 months of age and repeated at the 2-year health maintenance visit. It should also be performed at the 3-to-5-year visits if the child is at risk and not previously screened. If the LeadCare II identifies a child with an elevated level, the child should be retested with results sent to a reference lab for confirmation.

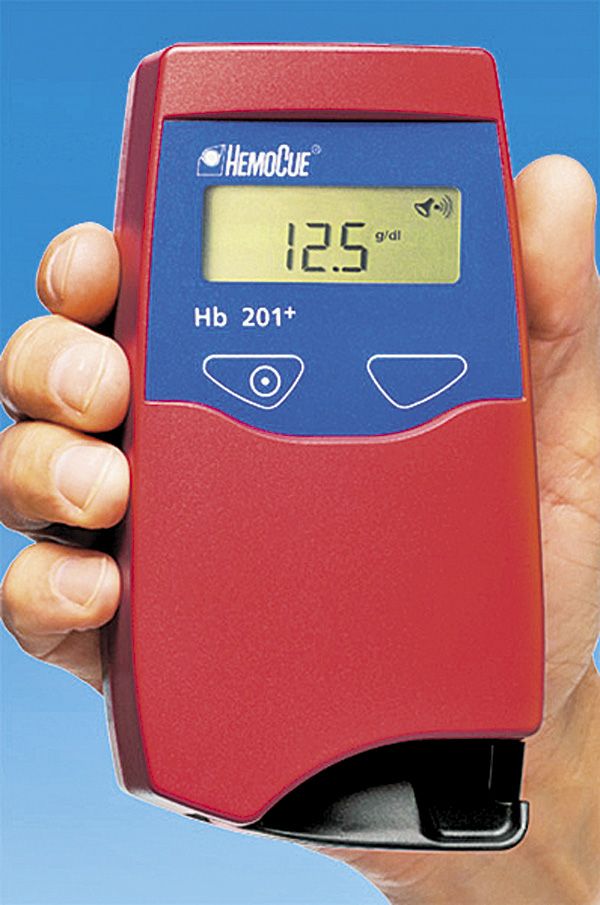

Children can also be screened for anemia (Table) at age 1 year when they are high risk. Many devices are available to make this possible at the time of the office visit. These include the well-known HemoCue Hb 201+ system (HemoCue AB; Angelholm, Sweden), and

HemoCue Hb 201+: Screens for anemia in seconds using finger-stick blood.several other devices that produce results from finger-stick blood in mere seconds. Unfortunately, there are no rapid tests that provide a quick assay of a patient’s iron status. So, if you want to combine a hemoglobin measurement with an assay to determine if the child has iron deficiency, you will need to send a child to your lab for a phlebotomy. Likewise, if you are screening sexually active teenage girls for chlamydia or gonorrhea, a urine test will need to be sent to your screening lab, although rapid tests are available for use with swabs obtained if a pelvic exam is performed. Point-of-care testing can also facilitate lipid screening when indicated. Screening for anemia in adolescent girls can be easily accomplished with the Masimo Pronto-7 device (Masimo; Irvine, California), which allows clinicians to screen for anemia transcutaneously. Unfortunately, as of this writing, this device doesn’t work reliably in toddlers.

Pronto-7: Use to screen older children for anemia transcutaneously. Photo courtesy of Masimo Corporation.

Make immunizations less traumatic

Perhaps the most stress-producing part of the visit for patient and parent is the administration of immunizations. Consider distraction techniques and devices that may blunt the pain associated with injections. These options include the Shot Blocker from Bionix Medical Technologies (Toledo, Ohio), a studded piece of plastic that presses against the skin at the injection site, blocking transmission of pain. The Buzzy Pain Relief System (MMJ Labs; Atlanta, Georgia) is a vibrating, kid-friendly gadget that is attached to a cold pack and placed on the arm above the injection site. By

Buzzy Pain Relief System: Cold and vibration impulses dull discomfort from injections.overwhelming nerves with cold and vibration impulses, children are less likely to experience significant discomfort from injections. Lastly, the PharmaJet (PharmaJet; Golden, Colorado) is a needle-free injection system that may eventually prove to be the best device for immunizing children. Studies are currently under way that hope to demonstrate that equivalent antibodies levels can be achieved with PharmaJet immunizations compared with those administered via standard needle injections. This would be a very good thing because PharmaJet injections are less painful and less frightening to our needle-phobic patients.

Education

An important component of the well visit is educating parents and children regarding age-appropriate issues. These include, but are not limited to, weight concerns, getting appropriate exercise, accident-proofing a home, sunblock and insect repellent use, and avoiding firearm injuries-just to name a few. Teenagers should be educated regarding depression, smoking, drug use, and other risk behaviors. Undoubtedly, we identify issues at our well-child visits that need follow-up. Education handouts help parents understand issues identified, be they bed-wetting, depression, or a murmur not previously heard. Practices should be prepared to hand out information regarding such issues. A more efficient way of educating parents following a visit is to direct parents to your Web portal that has appropriate content for them to review, or use the CHADIS system to provide not only information about medical problems, but also local resources in the patient’s own community. The most efficient practice will e-mail parents a copy of the visit summary, health and immunization forms, and any information sheets deemed appropriate.

The future of preventive health care visits

In the future, we can anticipate that we will have more sophistical office-based technologies that will make our preventive care visits even more efficient. I am especially looking forward to the introduction of devices that will give us the ability to perform screenings that will no longer require painful phlebotomy, or immunizations that no longer need painful injections. That day, hopefully, is not far off.

REFERENCES

Kemper AR, Mahle WT, Martin GR, et al. Strategies for implementing screening for critical congenital heart disease. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):e1259-e1267.

Baker RD, Greer FR; Committee on Nutrition American Academy of Pediatrics. Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1040-1050.

Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: summary report. Pediatrics. 2011;128(suppl 5):S213-S256.

Miller JM, Lessin HR; American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Ophthalmology; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists. Instrument-based pediatric vision screening policy statement. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):983-986

Bright Futures, American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. Bright Futures Web site. http://brightfutures.aap.org/clinical_practice.html. Published 2008. Accessed June 3, 2013.

DR SCHUMAN is adjunct associate professor of pediatrics at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire. He is also section editor for Pediatrics V2.0 and an editorial advisory board member for Contemporary Pediatrics. He has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.