Sorting out elbow injuries

When a child falls hard on an outstretched hand, something in the elbow may stretch or break. Elbow away confusion about these injuries by boning up on the most common problems and how to manage them.

Sorting out elbow injuries

Cover story

By William L. Hennrikus, MD, Brian A. Shaw, MD, and Joseph A. Gerardi, DO

When a child falls hard on an outstretched hand, something in the elbow may stretch or break. Elbow away confusion about these injuries by boning up on the most common problems and how to manage them.

Diagnosing and managing elbow injuries in children is a challenge. Although pediatricians can quickly identify some elbow fractures clinically and radiographically, other injuries are subtle and easy to miss. Radiologic identification of specific fractures is difficult because much of a child's elbow is radiolucent cartilage. Familiarity with the normal anatomy and ossification centers around the elbow is therefore helpful for evaluating an injured elbow. Pediatricians also need to know what the most common elbow injuries are, how to manage them, and when to refer.

The normal elbow and how it is injured

The elbow is a synovial hinge joint with articulations between three bones--the distal humerus, the head of the radius, and olecranon fossa of the proximal ulna. The elbow joint has two axes of motion. The elbow is flexed and extended at the u1no-humeral joint and moved from side to side at the radio- capitellar joint and proximal radioulnar joints. The olecranon fossa is normally filled with a small amount of fat.

A clear understanding of the vascular and neural anatomy is essential when evaluating an elbow injury. The brachial artery has many branches around the elbow, making collateral circulation abundant. Fortunately, this collateral blood supply is sometimes sufficient to maintain adequate circulation to the forearm and hand when an elbow fracture interrupts flow through the brachial artery. The brachial artery travels across the anterior elbow; the median nerve is on the brachialis muscle and medial to the biceps tendon. The u1nar nerve crosses the elbow behind the medial epicondyle and can be palpated when the elbow is flexed. During flexion, the u1nar nerve partially dislocates out of the sulcus in about one third of children.1 The radial nerve spirals around the posterior distal third of the humerus and travels through the lateral intermuscular septum across the elbow joint.

Various muscle groups about the elbow can displace fractures. The triceps inserts onto the tip of the olecranon and extends the elbow. The brachialis inserts onto the coronoid process of the ulna and is an elbow flexor. The biceps inserts via a prominent tendon onto the medial side of the radius on the tuberosity; it facilitates elbow flexing and allows the forearm to be suppinated (turned palm upward by rotating the forearm) The muscles that permit the forearm to be flexed and pronated (turned palm downward by rotating the forearm) originate from the medial epicondyle. The extensor forearm muscles originate from the lateral condyle (Figure 1).

The usual cause of elbow injuries in children is a fall on an outstretched hand. Falling directly on the elbow or having the arm pulled hard can also cause injury. Falls from monkey bars, roller blades, skate boards, bicycles, trampolines, and furniture are common. Many children have lax ligaments, which allow for hyperextension of the elbow and contribute to the high incidence of supracondylar fractures of the humerus.2

Clinical and radiologic evaluation

Begin your examination of a child with an injured elbow by inspecting the skin around the elbow carefully. An open fracture is an orthopedic emergency (Figure 2). Cover the wound with a sterile dressing, give the patient intravenous cefazolin 25 mg/kg and a tetanus booster if needed, and contact an orthopedic surgeon. An elbow injury that causes ischemia in the arm also is an emergency. Palpate the radial pulse at the wrist. If the pulse is absent and capillary refill is sluggish, splint the limb in the position of the deformity, and call your orthopedic surgeon immediately. Ischemia to the forearm muscles that is not recognized or not treated promptly can result in muscle necrosis and permanent elbow, wrist, and hand contractures (Volkman ischemic contracture).

Determining the status of the three major nerves of the arm can be difficult in an apprehensive child with a swollen, painful elbow. Test motor function by asking the patient to extend the thumb (radial nerve), flex the small finger (ulnar nerve), and flex the index finger or thumb (median nerve). Check sensation as well. The radial nerve supplies sensation to the back of the hand, the u1nar nerve to the front of the small finger, and the median nerve to the front of the thumb and index finger. Fortunately, nerve palsies associated with elbow fractures do not usually require emergency treatment because most are caused by stretching or contusion and recover spontaneously. Finally, examine the limb carefully at the shoulder and wrist to rule out a second associated injury.

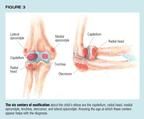

Evaluation of the injured elbow should include X-rays--an anteroposterior (AP) view of the extended elbow, a lateral view of the flexed elbow, and an oblique view. Knowing the age at which the six secondary centers of ossification (Figure 3) appear can avoid diagnostic confusion. The capitellum develops between 1 and 2 years of age, the radial head between 2 and 4 years of age, the medial epicondyle between 4 and 6 years of age, the trochlea between 9 and 10 years of age, the olecranon between 9 and 11 years of age, and the lateral epicondyle between 9.5 and 11.5 years of age. Ossification develops earlier in girls than in boys.3,4

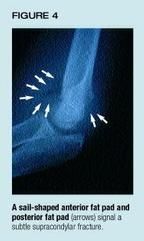

Assessment of the fat pads around the elbow is helpful when the injury is subtle.57 An anterior fat pad is normal unless the pad is in the shape of a ship's sail. A posterior fat pad or a sail-shaped anterior fat pad (visible on the lateral view) results when fluid in the elbow joint displaces the normal fat from the olecranon fossa (Figure 4). The most common cause of fluid in the elbow is a hemarthrosis (extravasation of blood into a joint) stemming from a fracture. A posterior fat pad may falsely appear to be present if the elbow is in extension. Abnormal fat pads also are associated with infection in the elbow joint or hemophilia.

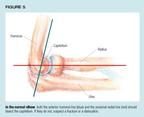

Other key radiologic signposts can help identify specific injuries, which are discussed below. On the lateral view, the anterior humeral line should bisect the capitellum.8 A change in this relationship may indicate a supracondylar, lateral condyle, or transphyseal fracture of the humerus. In addition, on all views, the proximal radius and radial neck should point to the capitellum (Figure 5). A subtle change in this relationship may indicate a Monteggia fracture or an elbow dislocation.

Although some physicians question the value of comparison views of the injured and noninjured elbow,3,9,10 they may differentiate a subtle fracture from a secondary center of ossification. In infants, ultrasound may be useful for evaluating the unossified elbow with suspected trauma.11 Even magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been considered helpful for defining articular injury of the fractured elbow.12 In our practice we rarely use MRI for this purpose though, since it usually requires a general anesthetic. We prefer to take the child to surgery for an arthrogram and immediate treatment.

Ten top elbow injuries

Three fractures--supracondylar, lateral condyle, and medial epicondyle fractures of the humerus-- are particularly common in children. Another seven injuries also are often seen. Table 1 lists these injuries.

Supracondylar fractures of the humerus are the most common elbow fracture in children. These fractures can be classified radiographically into three categories based on the degree of displacement:13 Type 1--nondisplaced; type 2--displaced posteriorly with an intact posterior cortex (Figure 6), as in a greenstick fracture, in which one side of the bone is broken while the other side is bent; and type 3--completely displaced without cortical contact (Figure 7). Any type 3 fracture should be referred urgently.

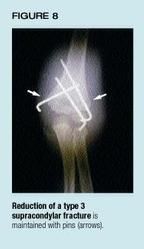

When the bone is not displaced, treat the fracture with a posterior splint and refer the patient to an orthopedic surgeon the next day for casting. After four weeks of casting, the fracture usually has healed nicely. Treatment of a partly displaced type 2 fracture is controversial. Some surgeons reduce and pin the fracture in the operating room, while others cast it in clinic. We recommend splinting the limb and calling the orthopedic surgeon for an opinion. A type 3 fracture requires a closed reduction under general anesthesia. The reduction is maintained by percutaneous pinning14 (Figure 8). In about 10% percent of type 3 supracondylar fractures you will find no pulse at the wrist; the orthopedic surgeon should be called immediately in this situation.15

Vascular and neurologic complications or deformities may follow treatment of supracondylar fractures. Compartment syndromes, though devastating, are rare and can be prevented with early recognition and urgent referral. Nerve palsies are common. Stretching or contusion causes most of them, requiring only observation. If no clinical or electromyographic evidence of nerve recovery is apparent after five months, exploration and neurolysis (release of the nerve sheet with a longitudinal cut) are indicated.16 A few supracondylar fractures will heal in varus, hyperextension, and medial rotation, resulting in a "gunstock" deformity of the arm (Figure 9). The deformity is cosmetic rather than functional and, in severe cases, can be corrected by humeral osteotomy.17

Lateral condyle fractures of the humerus are the second most common elbow fracture in children. This fracture can be classified radiographically by the degree of displacement and the extent to which the joint is affected. In type 1 fractures, displacement is minimal (<2 mm) and the fracture does not affect the articular surface of the distal humerus (Figure 10). In type 2 fractures, displacement also is minimal but the articular surface is affected. Type 3 fractures are grossly displaced and rotated and can be associated with an elbow dislocation (Figure 11).

Type 1 and 2 fractures can be splinted and the patient referred to an orthopedic surgeon the next day. Children with type 3 fractures should be referred urgently. Minimally displaced fractures are treated in a cast with careful follow-up. These fractures heal slowly and may require casting for up to eight weeks. A few displace while in the cast, making surgery necessary.

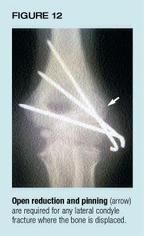

All displaced lateral condyle fractures require surgery--open reduction and pin fixation.18 The fracture must be reduced anatomically to restore the articular surface of the elbow joint (Figure 12). Compartment syndromes and nerve palsies are not associated with acute lateral condyle fractures, but this type of fracture is one of the few in children that does not always heal. The fracture fragment has a poor blood supply and if the fracture affects the articular surface, joint fluid may inhibit healing.

The minimally displaced lateral condyle fracture can be particularly troublesome to treat because it is often difficult to visualize on radiographs.19 When treatment is inadequate, the result can be a more serious displacement, nonunion, permanent deformity, late u1nar nerve palsy, and impaired function. Other complications of lateral condyle fractures include avascular necrosis stemming from reduced blood supply to the lateral condyle at the time of injury or during surgery, and mild varus deformity caused by stimulation and overgrowth of the lateral physis.

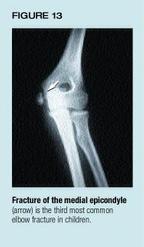

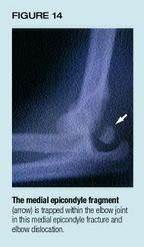

Medial epicondyle fractures of the distal humerus are the third most common elbow fracture (Figure 13) in children. The typical patient is an adolescent gymnast, wrestler, or football player. The medial epicondyle is an apophysis, and the last growth center in the elbow to fuse. In a fracture, the apophysis is pulled off the bone by the muscle and ligament attachments and is displaced distally and medially. About 50% of medial epicondyle fractures occur with an elbow dislocation. Sometimes the medial epicondyle becomes entrapped within the elbow joint (Figure 14). If the fragment remains in the joint, degenerative arthritis may develop; thus, radiographs must be evaluated carefully. An entrapped fragment can be mistaken for the trochlear ossification center. Comparison radiographs may be helpful.

Treatment of medial epicondyle fractures is controversial. The minimally displaced fracture (<5 mm) that is not in the elbow joint can be splinted and the patient referred to the orthopedic surgeon the next day. Fractures displaced more than 5 mm, especially in athletes, and entrapped fragments should be evaluated by the orthopedist as soon as possible. These injuries are treated by open reduction and internal fixation combined with early motion.20 The child with the rare fracture that produces u1nar nerve injury should also be referred urgently. Complications from this fracture are nonunion, valgus instability of the elbow, and valgus deformity of the arm.

Elbow dislocations typically occur in teenagers who fall during sports. Most elbow dislocations are posterior, but anterior, medial, and lateral dislocations are also possible. As many as half the children with elbow dislocations also have a fracture, and pre- and postreduction radiographs should be examined carefully. Clinically, an elbow dislocation may look like a supracondylar fracture with posterior displacement of the distal arm.

Most elbow dislocations can be reduced with closed methods in the emergency room, using intravenous sedation and analgesia; occasionally, general anesthesia is required. In our hospital, the orthopedic surgeon is called to the emergency room to perform the reduction; in other institutions, pediatric emergency-medicine physicians do the reduction. Traction along the axis of the forearm with the elbow flexed and a push on the back of the elbow usually is successful. The patient can be prone or supine.

A careful neurovascular exam should be performed before and after reduction to rule out entrapment of a neurovascular structure within the joint. Postreduction radiographs are taken to rule out an associated fracture. For the simple dislocation without fracture, the elbow is immobilized in a splint and sling for only a few days before a physical therapy early-motion protocol is begun. For a dislocation associated with a fracture, open reduction and internal fixation of the fracture are in order, followed by an early-motion protocol. For a dislocation associated with postreduction neurovascular entrapment, surgical exploration is recommended. Stiffness is the most common complication of elbow dislocations and seems to be related to prolonged immobilization.

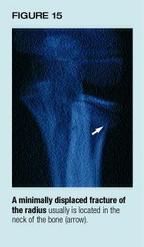

Radial neck fractures. Proximal radius fractures in children usually are of the neck or the physis (Salter type I or II). Pronation and supination may be more painful than flexion or extension. The oblique radiograph can help pick up subtle radial neck fractures. Minimally displaced fractures with less than 30 degrees of angulation or less than 3 mm of translation can be placed in a splint and referred to the orthopedic surgeon the next day (Figure 15). Refer patients with radial neck fractures that exceed these radiographic limits of displacement urgently to an orthopedic surgeon for closed reduction and, in some cases, open reduction and internal fixation (Figure 16). Complications of radial neck fractures include loss of motion--particularly from side to side--premature physeal closure, overgrowth of the radial head, avascular necrosis, and valgus deformity.

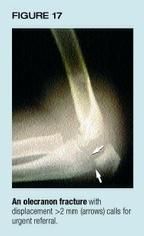

Olecranon fractures. The olecranon is the part of the ulna that articulates with the distal humerus. Olecranon fractures are uncommon but can occur with fractures of the radial neck or medial epicondyle. In addition to evaluating the fracture, verify the radial head position on all views to rule out a Monteggia fracture, as explained later. The olecranon apophysis can be confused with a fracture, and comparison radiographs of the opposite elbow may be helpful when the diagnosis is in question. Olecranon fractures may involve the articular surface of the humeral-ulnar joint. An isolated olecranon fracture with minimal displacement (<2 mm) can be immobilized in a posterior splint, and the patient referred to the orthopedic surgeon the next day. Children who have fractures with displacement of >2 mm should be referred urgently for open reduction and internal fixation (Figure 17). Complications of olecranon fractures include elbow joint stiffness and late arthritis.

Monteggia fracture-dislocations are rare but frequently missed injuries of the elbow. The injury consists of a fracture of the proximal third of the ulna plus a dislocation of the radial head. The ulna fracture is usually easily diagnosed but, unfortunately, the radial head dislocation is often missed. Since an isolated ulna fracture is uncommon in children, evaluation of all such fractures should include AP and lateral radiographs of the elbow to rule out radial head dislocation. On all radiographic views, a line drawn along the radial neck should intersect the capitellum of the distal humerus. Monteggia fracture-dislocations can be subtle, with only a minor greenstick fracture or bowing of the ulna (Figure 18).21 Monteggia fracture-dislocations merit an urgent referral to an orthopedic surgeon for closed reduction of the radial head dislocation and possible fixation of the ulna fracture. Failure to recognize this injury can lead to permanent radial head dislocation, valgus deformity of the arm, loss of pronation, and late radial nerve palsy. Reconstructive surgery can be performed at a later date but the results are often not gratifying.22

Transphyseal fractures, which typically occur in children younger than 3 years, are uncommon, though the fracture may be underdiagnosed because it can be mistaken for an elbow dislocation or supracondylar fracture. Most of the distal humerus is not ossified at this age; oblique radiographs (Figure 19) and occasionally an ultrasound may help to make the diagnosis.23 A skeletal survey is appropriate in any child with a transphyseal fracture that might have been caused by abuse.24 Nondisplaced transphyseal fractures can be splinted and the patient referred to the orthopedic surgeon the next day. A child with a displaced transphyseal fracture requires an urgent referral for closed reduction and pinning. Varus deformity may be the most common complication following this injury.

Nursemaid's elbow, which is not a fracture, is a very common e1bow injury in children. The injury typically occurs when a parent or babysitter yanks the child by the forearm. The child typically holds the affected arm face down and semiflexed and does not move it; pseudoparalysis results when the annular ligament that encircles the radial head is partially dislocated into the radiocapitellar joint (Figure 20). Most of these injuries occur in children younger than 7 years when the radial head is small and the annular ligament is thin and flexible.

How best to reduce nursemaid's elbow is controversial. We prefer to suppinate the slightly flexed elbow by applying gentle pressure over the radial head and flex the elbow as much as possible. Pronation of the elbow has also been reported as successful.25,26 Sometimes the physican can hear and feel a click as the radial head goes back into place, and the child quickly begins to use the arm. No immobilization is necessary.

When the diagnosis is unclear, X-rays before reduction is attempted can rule out subtle radial neck or lateral condyle fractures. Radiographs are also recommended if the child does not respond to the reduction maneuver. Complications stemming from nursemaid's elbow, though uncommon, include incomplete reduction, recurrent subluxation, and missing an occult fracture. We occasionally treat a recurrent subluxation by putting the injured limb in a long arm cast for three weeks.

Pseudoparalysis without obvious fracture. Sometimes acute elbow trauma in a young child is not apparent by clinical exam or standard radiographs. Careful examination of the oblique radiographic view can help identify an occult radial neck, lateral condyle, or transphyseal fracture. Comparison views can sometimes help to diagnose a subtle medial epicondyle or Monteggia fracture. Ultrasound may pick up a difficult transphyseal fracture and document an effusion. An occasional nursemaid's injury with normal radiographs may not reduce; in these difficult cases we often recommend splinting the arm for one week with a follow-up exam and radiograph. Finally, when the arm does not move normally but no fracture is evident, consider elbow joint infection. Most children fall often during play, and it is easy to mistakenly attribute swelling and pseudoparalysis to trauma. If septic elbow is a possibility, check the child's temperature, obtain a complete blood count and sedimentation rate, and, most important, aspirate the swollen elbow.27

Table 2 lists some "pearls" for diagnosing and managing elbow injuries.

The last word

Early recognition and appropriate referral are the keys to managing the 10 most common elbow injuries in children. Prompt action helps to minimize complications such as Volkman ischemic contracture, limb deformity, nonunion, and elbow joint stiffness.

DR . HENNRIKUS is Director of Sports Medicine, Valley Children's Hospital, Madera, CA, and Associate Clinical Professor of Surgery, UCSFFresno.

DR. SHAW is Medical Director, Pediatric Orthopaedic Surgery, Valley Children's Hospital, and Clinical Assistant Professor of Surgery at

UCSFFresno.

DR. GERARDI is an Orthopaedic Surgeon, Valley Children's Hospital, and Clinical Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at UCSFFresno.

REFERENCES

1. Zaltz I, Waters PM, Kasser JR: Ulnar nerve instability in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:567

2. Nork S, Hennrikus W, Gillingham B, et al: The relationship between ligamentous laxity and the site of upper extremity fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;8B:90

3. Rogers LF, Malave S, White H, et al: Plastic bowing, torus and greenstick supracondylar fractures of the humerus: Radiographic clues to obscure fractures of the elbow in children. Radiology 1978;128:145

4. Rogers LF. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow. Semin Roentgenol 1978;13:97

5. deBeaux AC, Beattie T, Gilbert F: Elbow fat pad sign: Implication for clinical management. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1992;37:205

6. Murphy WA, Siegel MJ: Elbow fat pad with new signs and extended differential diagnosis. Radiology 1997;124:659

7. Murray WA, Siegel MJ: Elbow fat pads with new signs and extended differential diagnosis. Diagn Radiol 1997;124:659

8. Skibo L, Reed NIH: A criterion for a true lateral radiograph of the elbow. Can Assoc Radiol J 1994;J45:287

9. Chacon D, Kissoon N, Brown T, et al: Use of comparison radiographs in the diagnosis of traumatic injuries of the elbow. Ann Emerg Med 1992;21:895

10. Kissoon N, Galpin R, Gayle M, et al: Evaluation of the role of comparison radiographs in the diagnosis of traumatic elbow injuries. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;15:449

11. Davidson RS, Markowitz RJ, Dormans J, et al: Ultrasonographic evaluation of the elbow in infants and young children after suspected trauma. J Bone Joint Surg 1994;76A:1804

12. Beltran J, Rosenberg ZS, Kawelblum M, et al: Pediatric elbow fractures: MRI evaluation. Skeletal Radiology 1994;23:277

13. Gartland JJ: Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1959; 109:145

14. Gerardi J, Houkom J, Mack G: Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children-treatment by closed reduction and percutaneous pinning. Ortho Review 1989; 18:1089

15. Shaw R, Kasser J: Management of vascular injuries in displaced supracondylar humerus fractures without arteriography. J Ortho Trauma 1990;4:25

16. Culp RW, Osterman AL, Davidson RS, et al: Neural injuries associated with supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1994;72A:1211

17. Voss FR, Kasser JR, Trepman E, et al: Uniplanar supracondylar humeral osteotomy with preset Kirshner wires for posttraumatic cubitus varus. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:471

18. Hennrikus W, Millis M: The dinner fork technique for treating displaced lateral condyle fractures in children. Ortho Review 1993;14:1278

19. Gillingham BL, Rang M: Advances in children's elbow fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;15(4):419

20. Case S, Hennrikus W: Treatment of displaced medial epicondyle fractures. Am J Sports Med 1997;25:462

21. Lincoln T, Mubarak S: Isolated traumatic radial head dislocations. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:454

22. Rogers WB, Waters PM, Hall JE: Chronic Monteggia lesions in children. J Bone Joint Surg 1996;78A:1322

23. Markowitz RL, Davidson RS, Harty NIP, et al: Sonography of the elbow in infants and children. Am J Roentgenol 1992;159:829

24. DeLee JC, Wilkins KE, Rogers LF, et al: Fracture-separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg 1980; 62A:46

25. Snellman 0: Subluxation of the head of the radius in children. Acta Orthop Scand 1959;28:311

26. Macias CG, Bothner J, Wiebe R: A comparison of suppination/flexion to hyperpronation in the reduction of radial head subluxations. Pediatrics 1998;102:e1O

27. McBride M, Hennrikus W: Pseudoparalysis of the arm in children. Ortho Trans 1997;18:456

William Hennriuks,Brian Shaw. Sorting out elbow injuries. Contemporary Pediatrics 1999;10:154.