Strabismus : Getting it straight

Strabismus is more than a misalignment of the eyes. It affects how well a child sees and occasionally signals pathology. Identifying the condition promptly and knowing when to refer are crucial.

Strabismus: Getting it straight

By Darron A. Bacal, MD, and Martin C. Wilson, MD

Strabismus is more than a misalignment of the eyes. It affects how well a child sees and occasionally signals pathology. Identifying the condition promptly and knowing when to refer are crucial.

A 2-year-old girl recently was referred to a pediatric ophthalmologist for a strabismus evaluation after her pediatrician noticed that the child's left eye was crossing. The examination revealed a retinoblastoma, which caused a strabismus. Because the child's pediatrician was aware that strabismus can be a sign of intraocular pathology, the neoplasm was detected before it spread beyond the eye, markedly decreasing the risk that the tumor would be life-threatening.

Although the cause of strabismus is rarely something as serious as retinoblastoma, this anecdote illustrates how timely evaluation of strabismus can save a child's vision and occasionally even a child's life. Pediatricians should feel comfortable performing the initial evaluation of a child with suspected strabismus. They need to know what to look for in the physical examination, how to take a pertinent history and recognize the more common types of strabismus, and when to refer.

Strabismus and amblyopia are related

In examining a child for ocular abnormalities, keep in mind the relationship between strabismus and amblyopia. Amblyopia can develop only during the first decade of life,1 and the earlier in life it appears the more severe it is likely to be. The child is considered to have amblyopia when the vision of one eye (rarely, both) is diminished despite correction with glasses for any refractive problem, or beyond what is expected after correcting any ocular pathology as fully as possible.2

Strabismus can cause amblyopia, and amblyopia can cause strabismus. An example of the latter would be when the vision loss produced by a unilateral infantile cataract results in amblyopia, which then leads to strabismus. A child with strabismus is at risk for developing amblyopia because the misalignment often leads to a preference for one eye. This can result in preferential development of visual pathway connections between the preferred eye and the brain, leading to reduced acuity in the nonpreferred eye. If the amblyopia does not improve or is not corrected during the first decade of life, it is permanent and irreversible.

During the first three months of life it is normal for an infant to display intermittent horizontal strabismus. Strabismus is considered "intermittent" if it occurs from time to time or is present only when the child looks in a particular direction (left or right, for example) or at a certain distance. The intermittent strabismus should completely resolve by 3 months of age.3 If it does not, promptly refer the infant to a pediatric ophthalmologist. The child with a constant strabismus merits a referral, whatever his or her age.

Making the evaluation

To appraise a child with suspected strabismus, take a history, check the red reflex and visual acuity, and evaluate ocular alignment.

History. If a parent has noted that her child's eyes are misaligned, begin by finding out when she first noticed the misalignment and how often it seems to be present. Are the child's eyes more likely to be misaligned when she is tired or sick, or is the misalignment constant? Does the child blink or squint frequently? This may signal intermittent strabismus and an attempt to relieve associated double vision (diplopia). Ask an older child if he experiences any double vision. Is there a family history of strabismus or amblyopia? Also review the past medical history. Certain conditions, such as prematurity or cerebral palsy, increase the risk of strabismus.4

Examination. Since strabismus may be the presenting sign of ocular pathology such as a cataract or retinoblastoma, always check the red reflex in each eye with a direct ophthalmoscope. Perform age-appropriate vision screening.5 Test each eye separately for acuity, occluding the eye that is not being tested.

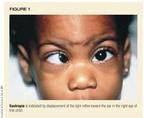

Evaluation of ocular alignment is crucial. In infants and children who cannot cooperate with cover testing, evaluation of the corneal light reflex can show the presence or absence of strabismus. In the Hirschberg light reflex test, the examiner holds a light near his own eye while the child fixates on a small toy or object. If the corneal light reflex is centered in each eye no strabismus is presentat that moment. If the reflex is off center toward the nose, the child has an exotropia (eyes that diverge). If the reflex is off center toward the ear (temporal displacement), the child has an esotropia (eyes that cross), as shown in Figure 1. Deviation off center of even 1 mm is significant, corresponding to approximately 7 degrees.

The light reflex test has several pitfalls, however. First, it won't detect an intermittent strabismus that is not present during testing. Second, if the light reflex is off center only slightly, it's easy to overlook the strabismus. Finally, in some rare situations, the light reflex may be off center even though the child does not have any strabismus. This can occur, for example, if the child has retinal damage from retinopathy of prematurity.

Cover tests provide another way to examine for strabismus. These tests require cooperation, attention, and good enough vision in each eye to focus on the testing target. Alternate cover testing can be performed using a distant target and a near target, as well as in various gaze positions. To perform a cover test, the examiner switches an occluder back and forth between the two eyes while the child fixates on the target (letter, number, or toy). If the child does not move his eyes, the eyes are "straight" (orthophoric). If the uncovered eye moves in toward the nose to focus on the target as the fixating eye is occluded, he has an exodeviation. If the uncovered eye moves toward the ear, he has an esodeviation. An ophthalmologist performs this test in conjunction with neutralizing prisms to quantify the deviation. Other types of cover tests allow the ophthalmologist to determine the type of deviation.

Testing ocular motility in side gaze and vertical gaze also is important. Less common causes of strabismus, such as Duane and Brown syndromes and cranial nerve palsies can be elucidated by evaluating eye movements.

No infant in need of an ocular examination is too young to have one and to be referred, if appropriate. A pediatric ophthalmologist can check ocular alignment, motility, and refractive error and perform a funduscopic examination in a child of any age.

Identifying and managing esodeviations

Esotropia is the most common form of strabismus and appears in several variations.

Pseudoesotropia. In an adult's eyes, an equal amount of white sclera typically is visible on either side of the iris. This makes the eyes appear straight. In infants and toddlers, however, a widened nasal bridge (telecanthus) or an extra fold of skin (epicanthus) can make less sclera visible on the nasal side of the eye than on the temporal side. This gives the eyes the appearance of being crossed, a condition called pseudoesotropia. (Figure 2). As infants grow and their facial structure changes, pseudoesotropia usually resolves. Pseudoesotropia does not rule out true strabismus, however. We have seen many children with pseudoesotropia and esotropia whose parents were told that their child would "grow out of it." Any infant or child whose ocular alignment is in question deserves an evaluation by an ophthalmologist.

Congenital (infantile) esotropia develops within the first six months of life.4 The patient often, but not always, has a family history of strabismus. Children with congenital esotropia usually are normal otherwise; however, a large percentage of children with neurologic disorders such as cerebral palsy or hydrocephalus have this type of esotropia. Congenital esotropia is associated with certain classic findings:

- Alternating fixation. The infant focuses (or fixates) with either eye, but not with both at once. Although this situation is not desirable since it precludes binocular function and development, alternating fixation is preferable to fixating with either the left or the right eye all or most of the time. Alternating fixation decreases, but does not eliminate, the risk of amblyopia.

- Cross fixation. The infant uses the left eye to focus on objects in his right field of vision and vice versa. Adducting the eyes in this manner may seem to the examiner to show an inability to move them toward the ears. This condition can mistakenly be diagnosed as bilateral sixth-nerve palsies. Consequently, when an infant with congenital esotropia cross-fixates, the physician must rule out bilateral sixth-nerve palsies by documenting full horizontal motility. To do this, patch one eye and force the child to track an object past the midline with the other.

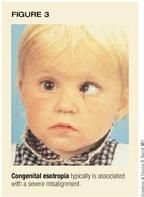

- Large angle, constant esotropia. The crossing of the infant's eyes usually is moderate or severe (Figure 3).

- Normal age-appropriate refractive error. Unlike other types of strabismus discussed below, congenital esotropia usually is associated with the mild farsightedness that is typical of infants.

- Nystagmus, which may be rotary or horizontal.

- Inferior oblique overaction (IOOA) and dissociated vertical deviation (DVD). These motility disturbances, which cause abnormal vertical eye movements, usually begin after the age of 2. Whether or not the infant's eyes were successfully realigned surgically is not believed to affect subsequent development of these conditions. A high percentage of children with congenital esotropia have IOOA and DVD.6

The goal in treating congenital esotropia is not only to realign the eyes but to restore some level of binocular function, which is possible only if the eyes are aligned before the child is 2.7 Recent data suggest that restoration of ocular alignment by around 6 months of age may maximize the ocular benefits of surgery.3 Surgery typically centers on weakening the medial rectus muscles of both eyes (Figure 4). In the child who has significant amblyopia as well as congenital esotropia, surgery can be confined to the poorer seeing eye by weakening the medial rectus muscle and tightening the lateral rectus muscle. If advisable, surgery also can be performed to correct the IOOA or DVD.

Accommodative esotropia is related to farsightedness. Normally, accommodation (focusing of the lens in the eye) is coordinated with inward turning of the eyes (convergence ) when viewing near objects. The focusing and inward turning are part of the synkinetic near response. Children who are very farsighted or have an abnormal relationship between accommodation and convergence may develop esotropia.

Children with accommodative esotropia are generally healthy and are diagnosed at an average age of 2 1/2 years.8 Parents typically describe an intermittent inward deviation of the eyes during visual concentration or near work. During periods of visual inattention, the eyes may remain straight. Accommodative esotropia can cause suppression of the image delivered to the brain by the nonpreferred eye, amblyopia, and loss of depth perception. A family history of this condition is common. Younger siblings of a child diagnosed with accommodative esotropia should be examined to rule it out.

Accommodative esotropia is treated with glasses to correct the farsightedness and patching for any associated amblyopia (Figure 5). If the esotropia is greater when the child focuses on near objects, bifocals may be necessary. The child should wear the glasses all the time if they eliminate the esotropia. You may want to reassure parents that it is natural for the esotropia to recur when the child takes off the glasses. Sometimes strabismus surgery is required when glasses do not adequately control the esotropia.

In most children, farsightedness worsens until about age 5, then gradually decreases until puberty. Glasses may need to be changed periodically and amblyopia monitored as the child grows. In amblyopic and strabismic children, ophthalmic examinations are usually required a few times a year during the first decade of life.

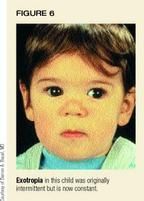

Severity of intermittent exotropia varies

Exotropia is usually intermittent at first, so the eyes work together normally during part of the day. The severity of this problem can range from rare episodes when the child is tired, with normal acuity and depth perception, to constant exotropia with amblyopia and loss of depth perception (Figure 6). If left untreated, intermittent exotropia generally gets worse, though it sometimes remains stable. Children with this condition are usually healthy, with no associated medical or genetic abnormalities, though some conditions such as the craniofacial syndromes (Apert or Crouzon) do increase the chance of exotropia. Average age at diagnosis varies widely, but most cases are recognized by the time the child is 5 or 6. Constant and persistent exotropia in an infant often signals other neurologic problems and calls for a neurology consultation.

Treatment must be tailored to the patient and depends on the frequency and duration of the exotropia, magnitude of the deviation, visual acuity, and binocular function.

- Observation is appropriate in mild cases with normal visual function

- Two nonsurgical treatments are recommended as first-line therapies in mild to moderate intermittent exotropia. (1) A prescription for glasses that is more myopic than is actually necessary can induce accommodation, which in turn induces convergence. This can help control intermittent exotropia.9 (2) Alternately patching the right eye and left eye on consecutive days can also help control intermittent exotropia. This technique is thought to disrupt active suppression.

- Surgery should be considered if a child's intermittent exotropia is worseningbecoming more frequent, lasting longer, or accompanied by decreased binocular function and amblyopia. Ideally, surgery is performed before the exotropia becomes constant.

Strabismus and torticollis

Torticollis, an abnormal head position, can be caused by bony abnormalities of the cervical spine or neck tumors. Many types of ocular pathology also can result in torticollis because an abnormal head position may allow the child to see better. An eye examination should be a part of the torticollis workup to rule out an ocular cause for the abnormality. Early intervention can improve the torticollis, reduce neck pain, and lessen the need for regular physical therapy. Ocular causes of torticollis include the following:

Congenital nystagmus. Children with this condition frequently assume a head position that minimizes the nystagmus and lets them see better. Other types of nystagmus, such as spasmus nutans, can also cause torticollis.

Oculomotor apraxia. The child compensates for an inability to maintain a horizontal gaze with jerky horizontal head thrusts.

Refractive error. In rare instances an extreme refractive error, such as significant farsightedness, can cause abnormal head postures, which are eliminated by prescribing the correct glasses.10

Ptosis. Children with significant bilateral ptosis need to assume a chin-up head posture to see.

Cranial nerve palsy. Fourth nerve palsy is a common cause of torticollis. The child will usually tilt her head to the shoulder opposite the palsy. In addition, she often turns her face chin down toward the palsy position, which minimizes the resultant strabismus and maximizes binocular function.

Other conditions. Duane syndrome, Brown syndrome, and congenital fibrosis are other conditions associated with strabismus that can result in torticollis.

Straight talk

The keys to maximum visual acuity and binocular function in infants and children with strabismus are early detection, diagnosis, and treatment. The infant with intermittent strabismus that persists beyond 3 months of age, a constant strabismus at any age, or torticollis whose origin cannot be determined merits a prompt referral to a pediatric ophthalmologist. Children who require glasses or patching need lots of encouragement and support. Compliance with patching is extremely variable and the major obstacle to successful treatment of children with amblyopia. The pediatrician can play an active role in ensuring that the patient adheres to the required therapy by reinforcing its importance during follow-up visits.

REFERENCES

1. Vaegan, Taylor D: Criticial period for deprivation amblyopia in children. Trans Ophthal Soc UK 1979;99:432

2. Bacal DA, Hertle RW: Don't be lazy about looking for amblyopia. Contemporary Pediatrics 1998;15(6):99

3. Wright KW, Edelman PM, McVey JK, et al: High-grade stereo acuity after early surgery for congenital esotropia. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:913

4. Holman RE, Merritt JC: Infantile esotropia: Results in the neurologic impaired and "normal" child at NCMH (six years). J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1986;23(l):41

5. Bacal DA, Rousta ST, Hertle RW: Why early vision screening matters. Contemporary Pediatrics 1999; 16(2):155

6. Nelson LB, Wagner RS, Simon JW, et al: Congenital esotropia. Surv Ophthalmol 1987;31(6):363

7. Ing MR: Surgical alignment for congenital esotropia. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus 1984;21(2):76

8. Swan KC: Accommodative esotropia: Long-range follow-up. Ophthalmology 1983;90:1141

9. Caltrider N, Jampolsky A: 0vercorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology 1983;90:1160

10. Havertape SA, Cruz OA: Abnormal head posture associated with high hyperopia. J AAPOS 1998;2(1):12

DR. BACAL practices pediatric ophthalmology in Milford, Branford, and Orange, CT. He is a Clinical Instructor in the Yale University Ophthalmology Department and affiliated with YaleNew Haven Hospital, New Haven, The Hospital of St. Raphael, New Haven, and Milford Hospital, Milford, CT.

DR. WILSON practices pediatric ophthalmology in Devon, PA, and is affiliated with the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Darron Bacal,Martin Wilson. Strabismus : Getting it straight. Contemporary Pediatrics 2000;2:49.