Telehealth: A primer for pediatricians

Whether you realize it or not, you have been practicing telehealth for years. By communicating with patients by telephone, you are managing their care at a distance.

Whether you realize it or not, you have been practicing telehealth for years. By communicating with patients by telephone, you are managing their care at a distance. “Managing care at a distance” is the essence of telehealth, and telehealth will play an increasingly important role for pediatric practices in the months and years to come. The topic of telehealth is so vast it will take 2 Peds v2.0 articles to do it justice. In Part 1, I’ll provide an overview of the capabilities of telehealth services. Next month in Part 2, I’ll discuss how you can integrate telehealth into your practice.

Telemedicine vs telehealth

A substantial number of academic medical centers are already providing services to remote communities using sophisticated (and expensive) telemedicine technologies. Using a video workstation linked to a remote diagnostic station manned by a nurse or medical assistant, a physician can interview a patient and perform a thorough exam. The assistant records the vital signs; examines the ears with a video otoscope; and examines heart and lungs via an electronic stethoscope. A high-definition video camera is used to examine the eyes; look in the mouth and throat; and examine suspect skin lesions. Depending on the need, electrocardiograms can be recorded and shared, and imaging studies can be reviewed as well. In other situations, the diagnostic workstation becomes mobile and enables specialists to examine patients in intensive care units or on hospital wards to make recommendations regarding care.

These kinds of scenarios describe what academic centers and tertiary medical centers refer to as telemedicine-providing remote healthcare utilizing telecommunication technologies-and these services have been available for well over a decade. The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) advises that “telemedicine” and “telehealth” in practice are often used interchangeably. From my observations made in researching this article, telehealth is most often used to describe the broader category of healthcare delivery that now includes mobile applications, call centers, and virtual medical visits as well as remote diagnostic and therapy services.

NEXT: The origins of telehealth

The origins of telehealth

The way we communicate with our patients has slowly changed over the years. We have always sent patients letters to inform them of lab and x-ray results and to remind them to schedule an office visit. We still do so today, although many practices are communicating results today via “patient portals” described in previous Peds v2.0 articles. Our pediatric answering services have evolved into call centers staffed by pediatric nurses who utilize phone triage protocols developed by Barton Schmitt, MD. As a consequence, the on-call pediatrician receives fewer phone calls than we did in years past.

Read: Renovating your medical home

With the development of the iPhone in 2007 and iPad in 2010, parents have discovered they can help care for their child by sharing snapshots of transient rashes as well as recording videos of “funny” breathing noises or questionable seizure activity. These devices also keep parents and their children entertained while waiting for a medical provider to enter the exam room, replacing our tattered and out-of-date magazines and germ-accumulating (but safe!) office toys. Now there are numerous medical apps as well as dozens of gizmos that enable our smart devices to improve the medical care we provide patients. All this is telehealth. It is growing rapidly and providing opportunities for physicians to provide better healthcare.

Surveys on telehealth

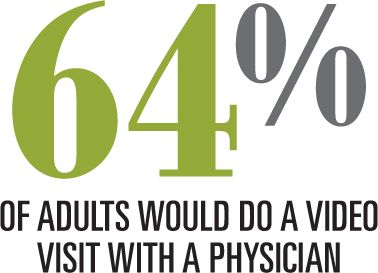

Harris Interactive conducted a poll of over 2000 adult patients in December 2014 to solicit their opinions regarding video medical visits. The study was commissioned by the American Well (Boston, Massachusetts) direct-to-consumer (DTC) telehealth service (www.americanwell.com).

In this poll, 64% of respondents said they would be willing to participate in a video visit, with the majority citing convenience as the major factor. If patients required middle-of-the-night care, 44% said they would use the emergency department (ED); 21% said they would use video visits; and the remainder said they would consider using a 24-hour nurse line or an online symptom checker, or call an ambulance. Parents with children in the household would choose videoconferencing 30% of the time. In response to questions regarding what medications patients would expect to get via video visits, patients said medication refills, birth control pills, antibiotics, and prescriptions for chronic conditions.

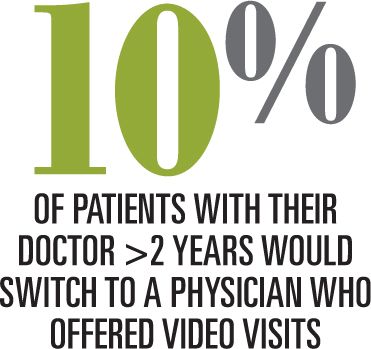

What is most telling is that 7% of respondents who were with their provider less than a year would switch to a physician who offered video visits, while 10% of patients who had been with their doctor for more than 2 years would switch for this reason. My interpretation of this information is that whereas most parents are devoted to the primary care physician who manages their patient-centered medical home (PCMH), a significant number of patients would consider moving from 1 PCMH to another, based on the availability of video visits. (See “DTC telehealth services threaten the medical home")

Another Harris Survey of 2311 adults conducted in the summer of 2012 told another interesting story. At the time, only 17% of those surveyed had online access to medical records, while 65% considered this access either very important or important. Also at the time, only 12% had e-mail access to their physician while 53% considered this either important or very important. Other services deemed important by healthcare consumers included the ability to make an appointment online as well as the ability to pay medical bills online. Interpretation: We need to improve our ability to communicate with patients electronically and move beyond the traditional phone call.

NEXT: What does the evidence say?

The evidence

For those of us unfamiliar with telehealth, it would appear that providing quality health services on par with those of an in-person visit would be difficult to do remotely. It would seem that it would be difficult to get an adequate look at the throat, ears, and more that would be sufficient for a pediatrician to arrive at a diagnosis! Thanks to the long-standing efforts of Ken McConnochie, MD, MPH, and other innovators at the Golisano Children’s Hospital, University of Rochester Medical Center, New York, a model of pediatric telehealth services was developed more than a decade ago that proved beyond question that telehealth could indeed provide high quality "connected" healthcare.

Health-e-Access began as a well-funded research project in 2001, and over years it blossomed to involve 22 schools and daycares throughout the suburban Rochester area. The system connected pediatricians via workstations to trained telemedicine assistants at these remote locations who prepped the visit by recording vital signs; recording auscultated heart and breath sounds; and taking photos of children’s throat, eardrums, and rashes. In some situations, the assistants had the ability perform rapid strep testing as well. The physician then had a face-to-face video visit with the ill child, arrived at a diagnosis, sent prescriptions to a pharmacy, and even had an initial dose of an antibiotic administered by the assistant. In some situations, nebulized albuterol was administered if needed.

Between 2001 and 2013, Health-e-Access logged over 13,000 video visits. Several studies published by McConnochie and his associates showed that remote pediatric telehealth visits: 1) could accurately diagnose more than 85% of conditions evaluated; 2) saved parents from missing significant time away from work by expediting care; and 3) reduced ED visits by 22%.1-4 McConnochie convinced area insurance companies including Medicaid to pay for these visits for the duration of his study. Unfortunately, after research funding sources stopped 2 years ago, the program was downgraded to include only telephone care.

If you or your nurse could communicate via a video call with a patient, how many visits could be completed without the use of “sophisticated” diagnostic tools such as electronic stethoscopes and video otoscopes? Videoconferencing provides a visual assessment of an ill child that a telephone call simply cannot do. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a live video of an ill patient must be worth a million.

By utilizing video medical visits, one can easily determine if a child is truly “lethargic” or “having trouble breathing” as mothers so often describe. Parents who communicate with their pediatrician using camera-equipped tablets can enable you to view the pharynx as well as the eyes if conjunctivitis is suspected. Additionally, tablet cameras provide adequate resolution to identify many common rashes. Most of us would feel comfortable prescribing antibiotics for rashes we identify as tinea corporis, seborrhea, diaper rash, or impetigo without the benefit of an office visit. Likewise, conjunctivitis could be easily recognized and treated, as would patients with straightforward allergy symptoms.

Patients who require refills for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder meds also could be treated by virtual visits, as could counseling-based visits, or follow-ups of patients seen the previous day.

There already are adjunctive telehealth services you can recommend to help care for your patients. These include nutrition counseling, speech therapy, psychology services, and many others. There also are inexpensive devices available now or in the near future that parents can use in conjunction with smart devices to assist with diagnosis. These devices will be discussed in future Peds v2.0 articles.

Interested? Next month we will discuss regulations governing telehealth, examine payment concerns, and describe how you can begin implementing your own office-based telehealth program. Stay tuned!

REFERENCES

1. McConnochie KM, Conners GP, Brayer AF, et al. Effectiveness of telemedicine in replacing in-person evaluation for acute childhood illness in office settings. Telemed J E Health. 2006;12(3):308-316.

2. McConnochie KM, Conners GP, Brayer AF, et al. Differences in diagnosis and treatment using telemedicine versus in-person evaluation of acute illness. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6(4):187-195; discussion 196-197.

3. McConnochie KM, Wood NE, Kitzman HJ, Herendeen NE, Roy J, Roghmann KJ. Telemedicine reduces absence resulting from illness in urban child care: evaluation of an innovation. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1273-1282.

4. McConnochie KM, Tan J, Wood NE, et al. Acute illness utilization patterns before and after telemedicine in childcare for inner-city children: a cohort study. Telemed J E Health. 2007;13(4):381-390.

Dr Schuman, section editor for Peds v2.0, is clinical assistant professor of pediatrics, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and editorial advisory board member of Contemporary Pediatrics. He has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.

Anger hurts your team’s performance and health, and yours too

October 25th 2024Anger in health care affects both patients and professionals with rising violence and negative health outcomes, but understanding its triggers and applying de-escalation techniques can help manage this pervasive issue.