Uncharacteristic skin findings in a toddler with a history of dermatitis

The patient’s medical history included several episodes of mild diaper dermatitis and erythematous rashes during periods of teething.

Presentation and history

An 18-month-old girl who had been under the care of the same pediatrician since birth presented to her pediatrician’s office with a chief complaint of a persistent rash on her arms and legs. Her parents reported that the rash had been present for 2 weeks and had not improved despite the use of over-the-counter moisturizers. There was no reported history of fever, pruritus, or recent illnesses. The patient’s medical history included several episodes of mild diaper dermatitis and erythematous rashes during periods of teething, which were successfully managed with emollients and occasional low-potency topical corticosteroids. The patient was up to date on all vaccinations.

Her pediatrician had a long-term relationship with her parents, having followed the patient and her older sister for 3 years. The medical record did not document any social or behavioral concerns, and the parents consistently appeared engaged and conscientious in their children’s care.

Evaluation

On examination, the patient appeared well nourished and active. The patient’s vital signs were within normal limits. Multiple erythematous, scaly patches were noted on the arms and legs, with a distribution and morphology consistent with mild atopic dermatitis. There was no evidence of secondary infection, lichenification, or excoriations in these areas, suggesting chronic irritation rather than acute inflammation. Additionally, isolated erythematous papules were observed on the anterior trunk, which did not clearly align with the typical presentation of atopic dermatitis.

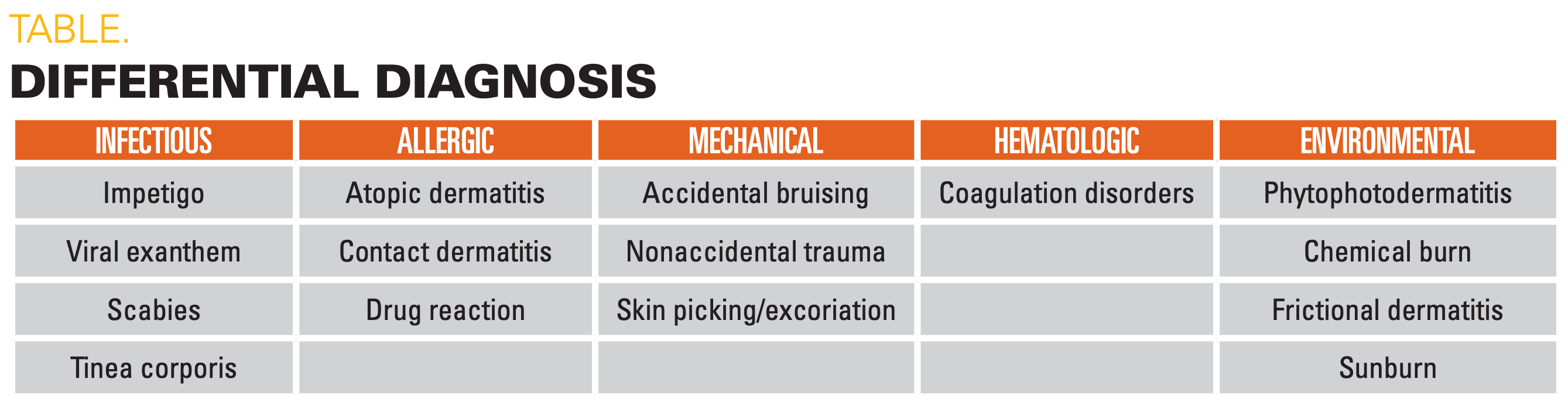

During the full-skin examination, several linear, reddish-hyperpigmented macules were incidentally observed on the patient’s lower back (Figure). These macules were arranged in an oval and ring-shaped configuration, often called lamp loop lesions. These findings, combined with the distribution and characteristics of the observed skin findings, contributed to a broader differential diagnosis that includes both common and more concerning etiologies (Table).

When gently questioned regarding any recent falls or injuries, the parents denied any significant incidents or noticeable trauma. The child showed no signs of tenderness or discomfort upon palpation of the macules, nor did she exhibit physical findings such as petechiae, purpura, or ecchymoses, which might suggest a coagulopathic condition. Laboratory tests, including a complete blood count and coagulation profile, were within normal limits, further ruling out bleeding disorders. No additional lesions were found on other areas, including the patient’s extremities, abdomen, face, or chest.

Clinical course and management

Given the atypical nature of the findings and the absence of a plausible explanation for the lamp-shaped reddish-brown macules, a referral was made to a child abuse pediatrician for further evaluation. The child abuse pediatrician conducted a comprehensive assessment, including a skeletal survey that did not reveal any additional evidence of fractures or other injuries. Despite the absence of overt injuries, the clinical decision to involve a child abuse pediatrician and use tools such as comprehensive assessments are supported by evidence indicating that early, subtle findings of patterned or region-specific bruises can be precursors to more severe outcomes if overlooked.1

Based on the findings, and in line with the duty of mandatory reporting, the pediatrician filed a report to Child Protective Services (CPS) to ensure the child’s safety. This decision was guided by the obligation to prioritize patient welfare and adhere to mandatory reporting laws, regardless of the long-standing relationship with the family or the absence of previous concerns.

Outcome

CPS conducted an investigation that ultimately revealed that the parents were responsible for the marks. This finding was particularly difficult to reconcile, given the long-standing, positive relationship between the pediatrician and the family and the absence of any prior concerns. The parents admitted to causing the injuries under circumstances that suggested a lapse in judgment rather than a pattern of abuse. They cooperated with CPS and participated in mandated counseling and supervision measures to ensure the child’s ongoing safety.

Discussion

Clinicians face many challenges in recognizing and addressing potential cases of child abuse, particularly when there is an established rapport with the family. Cognitive biases can arise from familiarity, potentially leading to the dismissal of atypical findings or even the reluctance to consider abuse as a possibility.2 There remains the importance of maintaining objectivity when considering all possible diagnoses—even in familiar patients—to prevent cognitive biases from affecting clinical judgment. In this case, a thorough physical examination and professional collaboration allowed for the identification of nonaccidental trauma despite the absence of obvious behavioral or social indicators and the initial difficulty in suspecting trusted caregivers.

The threshold for child abuse reports is and should be below the “beyond a reasonable doubt” used in typical criminal cases, and the index of suspicion should be high due to the imminent risk of harm.3 However, additional considerations should be made for the potential harms of erroneously reporting child abuse, which are significant and far-reaching. False positives can lead to unwarranted child protection interventions, including temporary or permanent separation from parents, which may have lasting negative effects on a child’s psychological and social development.4

Misdiagnosed cases, as illustrated by instances where medical conditions mimic signs of abuse, relay the importance of comprehensive assessments from a third independent party. Engaging an independent and experienced pediatrician to provide a second opinion can safeguard against erroneous reporting.5 This multidisciplinary approach ensures that rare medical conditions are considered and that the evidence is evaluated objectively. This balances the need for child protection with the risk of unnecessary familial disruption.

Furthermore, clinicians can use evidence-based screening tools to enhance the recognition of abusive injuries. For instance, the validated bruising clinical decision rule, known as TEN-4-FACESp, identifies specific bruising characteristics such as location on the torso, ear, neck, specific areas of the face, or patterned bruising to be predictive of abuse in children younger than 4 years.1 Integrating such clinical tools can aid in maintaining a high index of suspicion and ensure the early identification of at-risk patients while also balancing the risk of false positive reports.

Conclusion

Pediatricians should remain vigilant for signs of nonaccidental injuries, even in long-term patients with whom they have developed a positive relationship. Comprehensive physical examinations and an objective, evidence-based approach to differential diagnosis are essential in identifying potential cases of child abuse. Interprofessional collaboration and adherence to mandatory reporting guidelines is necessary while safeguarding the well-being of pediatric patients.

References:

1. Pierce MC, Kaczor K, Lorenz DJ, et al. Validation of a clinical decision rule to predict abuse in young children based on bruising characteristics. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e215832. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.5832

2. McTavish JR, Kimber M, Devries K, et al. Mandated reporters’ experiences with reporting child maltreatment: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e013942. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013942

3. Lyon TD. Child maltreatment, the law, and two types of error. Child Maltreat. 2023;28(3):403-406. doi:10.1177/10775595231176454

4. Crittenden PM, Spieker S. The effects of separation from parents on children. In: Cameron Kelly DC, ed. Understanding Child Abuse and Neglect - Research and Implications. IntechOpen; 2023.

5. Vlaming M, Sauer PJJ, Janssen EPF, et al. Child abuse, misdiagnosed by an expertise center: part I—medico-social aspects. Children. 2023;10(6):963. doi:10.3390/children10060963

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.