Update: Emergency contraception

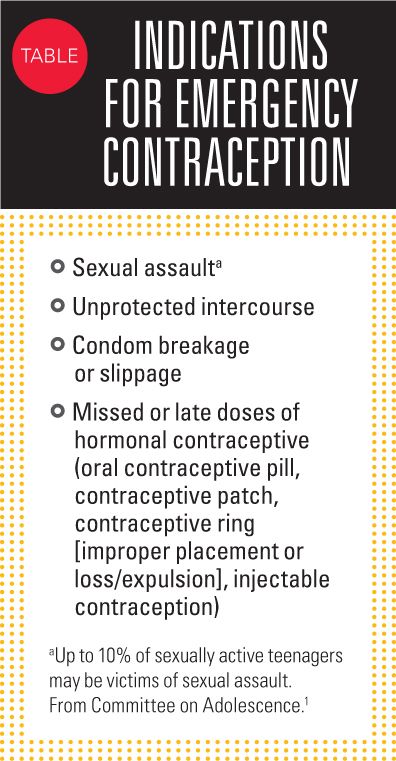

Emergency contraception is used to decrease the risk of pregnancy after unprotected or underprotected coitus.

Addendum to:UPDATE: EMERGENCY CONTRACEPTION

The article “Update: Emergency Contraception” appearing in the June 2015 issue of Contemporary Pediatrics references the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Policy Statement on Emergency Contraception.1 The Emergency Contraception policy statement was published in June 2012 and updated in February 2013 to reflect changes in availability of levonorgestrel products.

The topic of emergency contraception was also addressed in the AAP Policy Statement on Contraception for Adolescents2 and in the accompanying AAP Technical Report on Contraception for Adolescents,3 which were published online September 29, 2014. These publications note there are data suggesting that:

- Ulipristal acetate may have greater effectiveness than oral levonorgestrel at the end of the 5-day window of use.

- Ulipristal acetate may be more effective than levonorgestrel in people who weigh more than 165 pounds.

- Levonorgestrel emergency contraception is ineffective in women weighing more than 176 pounds.

The AAP Policy Statement on Contraception for Adolescents identifies the copper-bearing intrauterine device as the most effective method of emergency contraception, but notes it is less commonly used in adolescents.2

The AAP fact sheet on emergency contraception for parents and adolescents that is available on the HealthyChildren.org website was most recently updated on May 15, 2015.

REFERENCES

1. Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1174-1182. Erratum in: Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):362.

2. Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1244-e1256.

3. Ott MA, Sucato GS; Committee on Adolescence. Contraception for adolescents. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1257-e1281.

Emergency contraception is used to decrease the risk of pregnancy after unprotected or underprotected coitus (Table).1 In 2012, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a new policy statement on emergency contraception that supports its availability for adolescents. The policy statement provides information about the prescription status, dosing, mechanism of action, effectiveness, and safety of the available pharmacologic options and will enable clinicians to better inform patients on product use.

The AAP policy statement reviews the 2 medications that are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for emergency contraception-levonorgestrel and ulipristal-and combination oral contraceptives (the Yuzpe method). It does not discuss the intrauterine copper ring because that device is generally not available to pediatricians in their offices. The intrauterine copper ring as emergency contraception is reviewed in a recent update from the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP).2

The AAP policy recommends levonorgestrel as the first choice for emergency contraception based on data indicating it is more effective and better tolerated than the combination oral contraceptives, and, unlike ulipristal, does not require ruling out pregnancy prior to use.1 In addition, the AAP policy supports advanced provision of levonorgestrel emergency contraception, noting advanced provision has benefits of increasing the likelihood and timeliness of use without decreasing use of routine contraceptive methods.

Both the AAP policy and AAFP update emphasize the need for counseling and education on routine and emergency contraception and ensuring patient access, including to emergency methods.1,2 The AAP policy recommends this discussion be conducted with all male and female adolescents and families of disabled adolescents as part of routine anticipatory guidance in the context of a discussion on sexual safety and family planning.

An AAP fact sheet on emergency contraception for parents and adolescents was last updated in October 2014. It is available online at the Healthy Children.org website.

Emergency contraception methods

Emergency contraception is most effective when used within 12 to 24 hours of coitus.1,2 The options are reviewed below.

LEVONORGESTREL (PROGESTIN-ONLY METHOD)

In the United States, progestin-only emergency contraception products are available over the counter without age restrictions, although they may be kept behind the pharmacy counter in some stores.3

Levonorgestrel products dedicated to emergency contraception contain 2 levonorgestrel 0.75 mg pills (Plan B, Next Choice, generic), which can be taken either together or as a split dose 12 hours apart, or 1 levonorgestrel 1.5 mg pill (Plan B One-Step, Take Action, Next Choice One Dose, AfterPill, My Way, and generic).

The single and split-dose regimens are equally safe and effective,2 and the AAP policy statement recommends the single-dose method.1 According to the labeling for all 3 products, treatment should be initiated within 72 hours of intercourse. The AAP policy statement notes there are data showing efficacy of progestin-only emergency contraception for preventing pregnancy if it is taken within 120 hours of unprotected intercourse. There is preliminary evidence showing that the risk of failure is higher in obese individuals.2

Heavier menstrual bleeding is the most common adverse effect of using levonorgestrel emergency contraception.1 It also may cause earlier onset of menstrual bleeding, headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, and dysmenorrhea. The only contraindication to use of levonorgestrel for emergency contraception is known pregnancy, in which case the treatment will not be effective. Use during pregnancy does not pose potential risks to the fetus.

ULIPRISTAL ACETATE (ELLA)

Ulipristal acetate 30 mg is a progesterone agonist/antagonist available by prescription only for emergency contraception with no age restrictions.1

It should be administered within 120 hours after intercourse. Available evidence indicates it is marginally more effective than levonorgestrel at preventing unintended pregnancy when administered within 72 hours of intercourse.2 There is preliminary evidence showing that the risk of failure is higher in obese individuals.

Ulipristal can cause fetal loss when taken during the first trimester of pregnancy, but it has not been associated with teratogenic effects.1 Thus, prior to taking ulipristal, a pregnancy test is indicated if a patient’s period is more than 7 days beyond the date of her expected menstrual period. In addition, a return evaluation for ectopic pregnancy is advised if severe abdominal pain develops 3 to 5 weeks after dosing to evaluate the patient for the possibility of ectopic pregnancy.

The most common adverse effects of ulipristal are headache (18%), nausea (12%), and abdominal pain (12%).1 Its use also may delay onset of menses by up to 5 days. Other adverse effects include headache, fatigue, dizziness, back pain, and dysmenorrhea.

COMBINED ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

Combined oral contraceptives afford a convenient, readily accessible option to anyone who is already using this method for routine contraception.

Known as the Yuzpe method, this approach to emergency contraception involves ingestion of 2 doses of estrogen/progestin oral contraceptive pills taken 12 hours apart.1 The number of pills per dose may range from 2 to 5, depending on the product used. Each dose requires a total dose of ethinyl estradiol ≥100 mcg plus levonorgestrel ≥500 mcg (or dl-norgestrel ≥1 g). Tables listing the dose (number of pills) that need to be taken using available combined oral contraceptives are found in the AAFP update2 and on Princeton University’s emergency contraception website.3

Although off label, the Yuzpe method of emergency contraception has been declared safe and effective by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the FDA Reproductive Health Advisory Committee.1 It is most effective when used within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse. The Yuzpe method should not be used by anyone with contraindications to estrogen use.

The most common adverse effects are nausea (50%) and vomiting (20%).1 Ingestion with food does not mitigate these adverse effects, but the risk and severity can be reduced by taking an oral antiemetic (eg, meclizine 25 to 50 mg, or metoclopramide 10 mg) 1 hour prior to dosing.

INTRAUTERINE COPPER CONTRACEPTIVE (PARAGARD)

An intrauterine copper contraceptive may be able to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse when placed within 7 days.2 It is more effective than pharmacologic methods and can be considered by women who are not at high risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and who desire long-term contraception. Its safety and efficacy as intrauterine contraception have been established in women aged 16 years and older.4

STIs

In providing education on emergency contraception, patients should be counseled that the intervention does not protect against STIs, and about follow-up testing for an STI.1

Ethical dilemmas

The issue of pharmacist and physician refusal to provide emergency contraception to adolescents is also discussed in the AAP policy statement1 with reference to the AAP policy statement on refusal to provide information or treatment on the basis of conscience.5 As stated in the latter policy, pediatricians have a duty to inform their patients about relevant, legally available treatment options and a moral obligation to refer them to other physicians who will provide and educate about those services. The emergency contraception policy statement reminds pediatricians, “Failure to inform/educate about availability and access to emergency-contraception services violates this duty to their adolescent and young adult patients.”1

REFERENCES

1. Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):1174-1182. Erratum in: Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):362. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/130/6/1174. Accessed May 7, 2015.

2. Bosworth MC, Olusola PL, Low SB. An update on emergency contraception. Am Fam

Physician. 2014;89(7):545-550.

3. Princeton University. Emergency contraception website. Available at: http://ec.princeton.edu/emergency-contraception.html. Accessed May 7, 2015.

4. ParaGard T 380A [prescribing information]. Sellersville, PA: Teva Women’s Health, Inc; 2013.

5. Committee on Bioethics. Policy statement-physician refusal to provide information or treatment on the basis of claims of conscience. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1689-1693.

Ms Krader has 30 years’ experience as a medical writer. She has worked as both a hospital pharmacist and a clinical researcher/writer for the pharmaceutical industry and is presently a freelance writer in Deerfield, Illinois. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.

Having "the talk" with teen patients

June 17th 2022A visit with a pediatric clinician is an ideal time to ensure that a teenager knows the correct information, has the opportunity to make certain contraceptive choices, and instill the knowledge that the pediatric office is a safe place to come for help.

Meet the Board: Vivian P. Hernandez-Trujillo, MD, FAAP, FAAAAI, FACAAI

May 20th 2022Contemporary Pediatrics sat down with one of our newest editorial advisory board members: Vivian P. Hernandez-Trujillo, MD, FAAP, FAAAAI, FACAAI to discuss what led to her career in medicine and what she thinks the future holds for pediatrics.

Study finds reduced CIN3+ risk from early HPV vaccination

April 17th 2024A recent study found that human papillomavirus vaccination when aged under 20 years, coupled with active surveillance for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, significantly lowers the risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or cervical cancer.