Watercooler wisdom 2: Preventing (and treating) physician burnout

Physician “burnout” has become a popular topic in medical journals. It is worthwhile to discuss this important topic so we can recognize the symptoms of burnout, seek help when necessary, and change our work environment to prevent burnout and its consequences.

There has been a lot of activity around our watercooler lately. After having an exhaustive discussion around the watercooler regarding the issue of “patient satisfaction” (see Peds v2.0, Contemporary Pediatrics, August 2016), my colleagues and I are now engaged in conversations regarding “job satisfaction,” and are considering a variety of ways to improve our practice for our patients and for ourselves.

Physician “burnout” has become a popular topic in medical journals. It is worthwhile to discuss this important topic so we can recognize the symptoms of burnout, seek help when necessary, and change our work environment to prevent burnout and its consequences. Unfortunately, nearly 1 of every 2 physicians is experiencing burnout. The purpose of this article is to educate pediatricians regarding burnout symptomatology and, more importantly, how to remedy the problem when identified!

What is burnout?

Burnout is a well-recognized clinical syndrome associated with a loss of enthusiasm for work, negative feelings, and a low sense of personal accomplishment. Additional symptoms include fatigue, poor judgment, guilt, and feelings of ineffectiveness.1 In other words, if you don't look forward to coming to work, can't wait for your day to end, and believe you are losing your edge, you likely are experiencing burnout.

Recommended: How to improve your practice with a practice website

The condition was described in detail by psychologist Christina Maslach, PhD, professor of Psychology at the University of California-Berkeley. In the 1970s, she developed a burnout assessment tool called the Maslach Burnout Inventory, which is considered the gold standard for measuring burnout symptoms. We'll discuss performing a burnout "self-assessment" later in this article.

How common is burnout?

Unfortunately, numerous studies have looked at symptoms of physician burnout and the results suggest too many physicians are affected. A recent article published in Pediatrics, co-authored by Gary Freed, MD (member of the Contemporary Pediatrics Editorial Advisory Board), surveyed 864 early-career pediatricians to quantify burnout rates. The results of the study indicated that 30% of the surveyed pediatricians experienced burnout.2 However, on a positive note, the majority of pediatricians reported that they are satisfied with their career (83%) and life quality (71%).

Other surveys have looked at the physician population overall. One survey of 7288 physicians found that 45.8% experienced at least 1 symptom of burnout, with the highest rates of burnout noted in primary care and emergency physicians.3 In another survey, 6880 physicians were assessed using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, with 54.4% of the physicians reporting at least 1 symptom of burnout in 2014 compared with 45.5% in 2011.4

The newly published Physicians Foundation 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians is the most recent survey of physician’s opinions regarding medical practice, and for the first time it asked physicians questions about “burnout.” In this survey of more than 17,000 physicians, 48.6% of those surveyed reported frequent or constant feeling of burnout. More frequent burnout rates were reported by female physicians, as well as by physicians aged older than 45 years, and rates were comparably high in primary care and specialty care providers (Table 1).5 The unfortunate conclusion from all these surveys is that burnout is common among physicians and it appears to be on the rise!

NEXT: Causes and consequences

Causes and consequences

According to a recent Medscape survey,6 several factors contribute to physician burnout. These include:

· Having too many bureaucratic tasks;

· Spending too many hours at work;

· Insufficient income;

· Inefficient use of electronic health records (EHRs);

· Mandates of the Affordable Care Act (ACA);

· Having too many difficult patients;

· Having too many appointments in a day; and

· Having a difficult employer.

More: Disruptive technology and pediatric practice

Burnout may have dire consequences both for physicians as individuals as well as for the patients in their care. Higher substance addiction rates, divorces, and suicides are reported among individuals who feel they have experienced burnout. From a professional perspective, burned-out physicians are less likely to motivate patients to comply with recommendations and are more likely to make medical errors. Burned-out physicians are most at risk for malpractice, and often have lower patient satisfaction scores.

Prevention/treatment

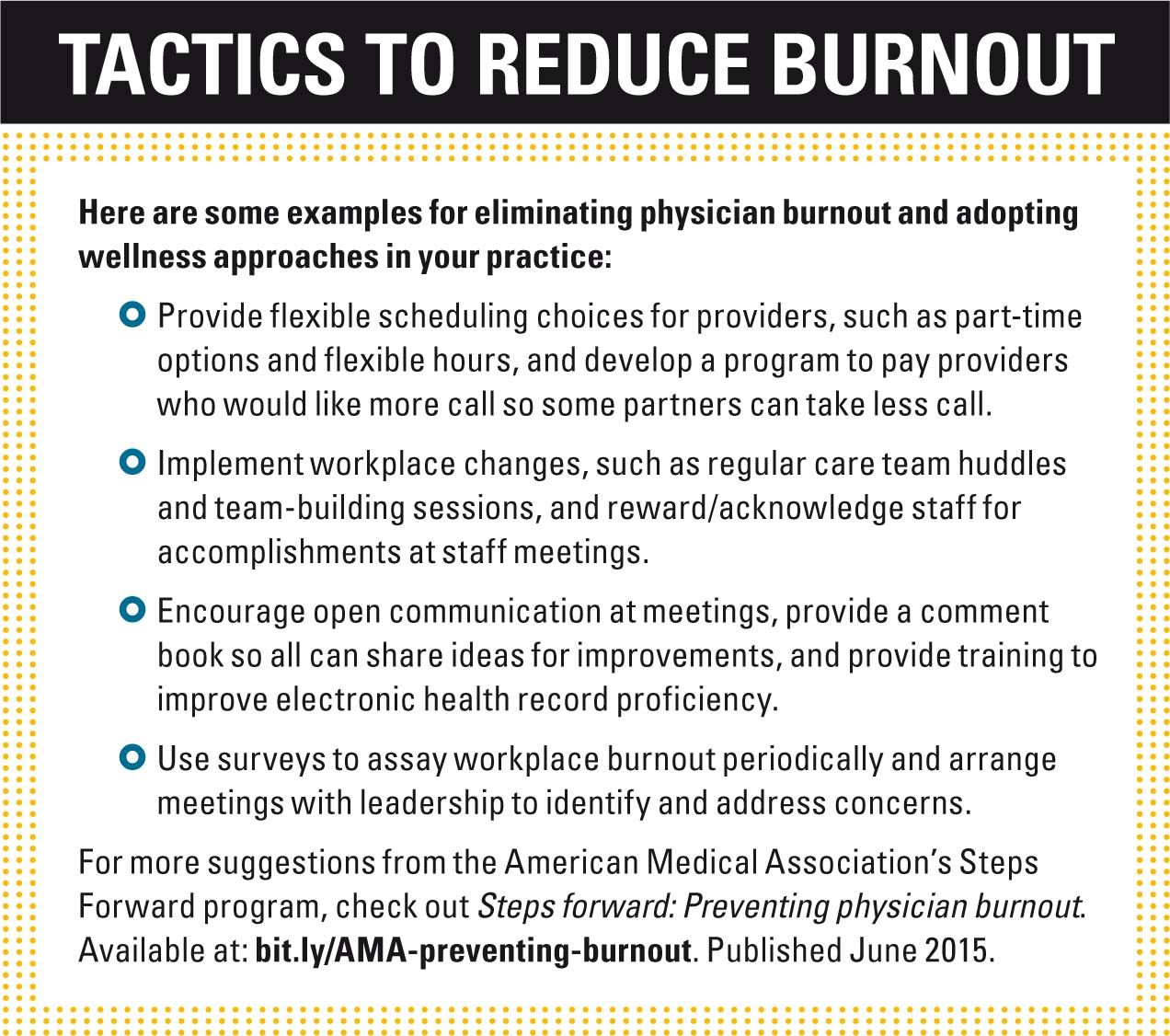

Given the anticipated physician shortage over the next decade, it is in the best interest of the American healthcare system to improve the working conditions of physicians. Many institutions are considering physician burnout rates as a “quality metric” and implementing programs to quantify and reduce provider burnout rates. The American Medical Association (AMA) Steps Forward program, developed in conjunction with the Medical Group Management Association, has an excellent educational model to facilitate assessment of physician burnout rates and provide solutions. You can view this module at www.stepsforward.org/modules/physician-burnout and consider implementing your own program with the tools provided. Some of the AMA’s suggestions for reducing burnout can be found in “Tactics to reduce burnout.”

I recommend that it would be prudent to determine if you suffer from professional burnout, or are at risk for developing burnout. You can take a version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory online at www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory for just $15. The results measure your feelings of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment, and compare your scores to 11,000 individuals drawn from the general population. If your emotional exhaustion and depersonalization scores fall in the top 10%, or feeling of personal accomplishment in the bottom 10%, you are burned out. I have taken the test and, fortunately, I’m pleased that I am not burned out yet (just crispy, but nowhere near “toast”).

NEXT: How to reduce stress

Improve the work environment

It is clear that we need to improve our working conditions and work environment, and, if possible, improve our ability to deal with stressful circumstances. Here is a strategy.

I have spent the last 4 years writing articles about how to improve pediatric practice. Look at “Make pediatric practice great again!” (Peds v2.0, Contemporary Pediatrics, April 2016) to review some of my more important suggestions.

Pediatricians can analyze and modify office workflow to streamline patient throughput; eliminate or reduce hassles by using patient portals so your staff responds to patients questions on your behalf; and use technology appropriately to expedite diagnosis and expand treatment options. Most importantly, physicians need to conquer inefficient EHRs. As discussed in my article “Expediting medical documentation” (Peds v2.0, Contemporary Pediatrics, January 2016), this can best be done by using scribes, virtual scribes, or mastering voice dictation software to expedite note completion.

Next: Improve your practice with behavior evaluation and management portals

Additionally, physicians need to learn to either ignore or sidestep some of the practice stressors associated with government oversight or insurance hassles. I believe it is foolish to participate in the ACA EHR incentive program and its many “meaningful use” requirements. Leave all Maintenance of Certification (MOC) requirements to the last year of your cycle, and use online prior authorization services so you and your staff can deal with the most important priority of your practice-good patient care. These measures alone will help reduce or eliminate many burnout-related stressors.

Reduce stress levels

Physicians need to reduce work- and life-related stressors, and there are many methods that can be used. Exercise has always been a very reliable way, not only to reduce stress, but also to improve overall health and focus. Consider going to a gym before work or during your lunch hour. Consider buying a treadmill or an elliptical trainer that you can use during the day. Alternative stress relievers may include activities such as yoga or meditation. Physicians should also schedule some breaks during the day to either catch up if needed, to exercise, or to just do something that relaxes you. Listen to music on your new iPhone 7. Buy a Jacuzzi and schedule a hot tub break during the day. Watch a movie on Netflix, read Contemporary Pediatrics, or play a video game.

Consider taking up a new hobby, such as needlework, or painting either with finger paints (very relaxing) or perhaps watercolors. These activities can be done at home or in your office.

Also important points are that you take plenty of vacation time and have a good team structure in your practice to accommodate busy times so that any 1 provider is never overwhelmed. This means having providers who will cover for one another and absorb excess patient visits if necessary, and that the practice is flexible enough to accommodate unfortunate life circumstances that affect everyone; ie, death of a loved one, a medical illness, divorce, and so on. We all need good support systems in place from friends, colleagues, and family.

Watercooler wisdom

After writing this article about burnout and how important it is to reduce office stress, I now frequently pause to contemplate the watercolor painting that hangs next to our watercooler. It’s a boat sailing on the ocean, a very relaxing view if even for a few moments before returning to patient care.

Now that you know the causes and consequences of burnout, you can begin your own self-assessment and even consider implementing a program at work to reduce burnout rates. I hope this information has proved helpful.

Send your recommendations or observations on physician burnout to catherine.radwan@ubm.com

REFERENCES

1. Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144(4):371-376.

2. Starmer AJ, Frintner MP, Freed GL. Work-life balance, burnout, and satisfaction of early career pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137(4):e20153183.

3. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385.

4 Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613. Erratum in: Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(2):276.

5. Physicians Foundation. 2016 Survey of America’s Physicians: Practice Patterns and Perspectives. Available at: http://www.physiciansfoundation.org/uploads/default/Biennial_Physician_Survey_2016.pdf. Published September 2016. Accessed October 12, 2016.

6. Peckham C. Physician burnout: it just keeps getting worse. Medscape. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/838437. Published January 26, 2015. Accessed October 12, 2016.

Dr Schuman, section editor for Peds v2.0, is clinical assistant professor of Pediatrics, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and editorial advisory board member of Contemporary Pediatrics. He has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.