When SSRIs make sense

When does your patient merit a serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor for depression, OCD, or another mental disorder? This review of the effectiveness of these agents and their sometimes serious side effects will help you decide. The authors also offer tips on choosing the right SSRI and dosage.

DR. WALSH is Clinical Assistant Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, and Chief of the Obsessive-Compulsive/Tourette's Disorders Clinic at Riley Hospital for Children, Indianapolis.

DR. McDOUGLE is the Raymond E. Houk Professor of Psychiatry, Pediatrics, and Neurobiology and Director of the Section of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine. He is Chief of the Autism/Pervasive Developmental Disorders Clinic at Riley Hospital for Children.

When SSRIs make sense

By Kelda H. Walsh, MD, and Christopher J. McDougle, MD

When does your patient merit a serotonin specific reuptake inhibitor for depression, OCD, or another mental disorder? This review of the effectiveness of these agents and their sometimes serious side effects will help you decide. The authors also offer tips on choosing the right SSRI and dosage.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are prescribed more often than any other psychotropic medication except stimulants. SSRIs available in the United States are, in order of approval, fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), paroxetine (Paxil), fluvoxamine (Luvox), and citalopram (Celexa). Fluoxetine and sertraline are among the 10 medications--medications, not psychotropics--most often prescribed for off-label use in children, with 2 million prescriptions filled for 5- to 10-year-olds in 1994.

SSRIs are relatively safe drugs, but psychotherapy delivered by a skilled child psychotherapist is a safer alternative for many children and should be considered for all children and adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Given the limited data on SSRI use in children and adolescents and the possibility of serious side effects, it appears that SSRIs may be used too often and psychotherapy not often enough.

Although primary care physicians write the vast majority of prescriptions for SSRIs, determining when to use an SSRI and which to choose can be confusing for the general pediatrician. We will review the effectiveness of SSRIs for specific disorders and address the side effects, pharmacology, and safety of these drugs.

Which conditions respond to SSRIs?

Many investigations of the efficacy of SSRIs for particular conditions have been controlled studies. In addition, open-label studies have helped to define dose strategies; in these studies, patients and clinicians know what agent is being used, the clinician has some flexibility in determining the dosage, and there is no placebo control group. Dosage ranges remain poorly defined, however; we will refer to dosages in mg/kg/day when possible.

Major depressive disorder. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommends psychotherapy as the initial treatment for mild to moderate depression, and SSRIs as the "antidepressants of choice."1 The academy notes that SSRIs are "never sufficient as the sole treatment"; management should include psychotherapy.

Fluoxetine and sertraline have been shown to be effective in childhood depression at dosages titrated to 20 mg/day (fluoxetine) and 200 mg/day (sertraline).24 In a 96-patient study of fluoxetine, only 31% of patients were in remission five weeks after starting the medication, however.2 In open-label studies, patients have responded to lower dosages of SSRIs than in controlled studies; one open-label study, for example, reported 73% remission on a mean of 127 mg/day of sertraline in a 22-week period.5 There have also been reports of responses to low dosages: In two instances, adolescents who did not respond to tricyclic antidepressants benefited from as little as 5 mg/day of fluoxetine, while children responded to a mean of 16 mg/day of paroxetine.6,7

SSRI dosages in children with major depression should be increased aggressively until symptoms resolve. Continue full-dose therapy six to 12 months after full remission; a six-week taper may prevent relapse. Longer maintenance treatment benefits patients with histories of severe or chronic depression.1 Depressed children who are losing weight or who are suicidal, homicidal, or hallucinating should be referred to a child psychiatrist.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Open-label and double-blind placebo-controlled studies suggest that SSRIs are effective in OCD in children, sometimes with concurrent psychotherapy.810 Sertraline and fluvoxamine have Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for children as young as 6 and 8, respectively. As in adults, mean dosages for OCD are higher than those for depression: 200 mg/day of sertraline (for children as young as 6), and 50 to 200 mg/day of fluvoxamine.9,10 Children 12 and older are much less responsive to fluvoxamine than younger children. Although most OCD studies have used high target doses, a recent study in adults shows that 50 mg/day of sertraline is as effective as 200 mg/day. (A target dose is the minimum effective dose targeted by the physician, based on the nature of the disorder and the size of the child.)

Exposure and response prevention (E/RP) is effective psychotherapy for OCD and a good alternative for children and adolescents unwilling or unable to take SSRIs. In E/RP a patient is exposed to a feared situation--a germ-obsessed child touches a succession of dirty objects, for example--and refuses to allow himself to respond with rituals like excessive handwashing. Child E/RP therapists are scarce; consultation with the Obsessive-Compulsive Foundation may be helpful (www.ocfoundation.org). OCD patients should be at the target SSRI dose for eight to 10 weeks; 30% symptom reduction is a good response.11 Symptom reduction can be measured by having the patient report how much time, on average, she spends each day on obsessions and compulsions; the patient and family report on changes in school and social functioning. Relapse off medication is common,11 though many patients learn to manage their symptoms with E/RP.

Social phobia and selective mutism. One of the better-studied childhood anxiety disorders, selective mutism is also the rarest and may be a variant of social phobia. Selective mutism usually becomes apparent for the first time when a child in kindergarten is unable to speak in the classroom, even after attending school for months. Fluoxetine has been effective in open-label and double-blind, placebo-controlled studies, though the drug is more likely to reduce anxiety than to increase comfort in public speaking.12,13 Children from 5 to 9 years old on 20 mg or more of fluoxetine daily for at least nine weeks had the best response.

Other forms of social phobia, also known as social anxiety disorder, are rare before puberty. SSRIs are clearly the medication of choice for adults with social phobia; paroxetine was recently approved by the FDA. Child and adolescent studies of social phobia are limited to open-label studies spanning many anxiety disorders; response rates are very promising at mean doses of 0.7 mg/kg/day in 9- to 17-year-olds.13,14

Other anxiety disorders. Although controlled childhood studies of panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and simple phobias have not been published (an NIMH fluvoxamine study is pending), SSRIs appear to be useful. One open-label study suggests that separation anxiety disorder is particularly responsive to SSRIs and panic disorder less so.15 Medications are not indicated for simple phobias, such as fear of heights, dogs, and thunderstorms, but consider SSRIs as an adjunct to psychotherapy in other anxiety disorders. The efficacy of tricyclics against childhood anxiety disorders has not been proved, despite controlled studies. SSRIs are more appropriate than benzodiazepines, which do not appear to be effective in children and may cause withdrawal, a loss of inhibition, irritability, and oppositional behavior.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The only published double-blind placebo-controlled study of SSRIs in adults with PTSD shows that rape victims respond well to fluoxetine, but combat veterans do not.16 Two small adult open-label studies of sertraline have been positive. The PTSD literature emphasizes prompt psychotherapy--using techniques that promote mastery of the event and stress management techniques--as the treatment of choice. Prescribe medication only for patients with debilitating symptoms.

Eating disorders. Fluoxetine is approved for bulimia in adults. No SSRI is approved for anorexia, for which there are no controlled drug studies in children or adolescents. The Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study of 387 adults demonstrates that 60 mg of fluoxetine per day is clearly superior to 20 mg/day or placebo.17 SSRI utility in acute anorexia has yet to be demonstrated; starvation-induced depletion of tryptophan, which is the precursor of serotonin, and neuroendocrine and neuropeptide abnormalities may reduce the effectiveness of SSRIs until the patient gains the weight she has lost. At this point, SSRIs are most often used for depression or obsessive-compulsive symptoms (perfectionism, and symmetry/ordering compulsions) that occur after weight is regained, though open-label studies have not shown consistent benefit.18

Autism. Many serotonin abnormalities, including elevated whole-blood serotonin, have been identified in some children with autism. Perseverative or compulsive behaviors in autistic children may resemble those of OCD. In eight of 15 adults in a controlled trial, fluvoxamine resulted in fewer repetitive thoughts and behaviors, less aggression, and improved social relatedness, particularly in use of language.19 In a controlled investigation, fluvoxamine was less effective and less well tolerated in children and adolescents with autism than it has been shown to be in adults (McDougle, unpublished data).

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Little support exists for using SSRIs to treat ADHD; buproprion and tricyclics have better track records.20 In one open-label study of children and adolescents with ADHD and major depression, psychostimulants combined with SSRIs had good results.21 In a study of 19 children with ADHD, many of whom also had conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder, fluoxetine produced significant improvements, according to ratings by parents, teachers, and physicians.22

Trichotillomania. No single medication can be recommended for children with this hair-pulling disorder. A dosage of 75 mg of fluoxetine was effective in one placebo-controlled study, but other trials of the agent did not produce improvement.23 Clomipramine appears to be the most effective medication studied.24 Motivated children and adolescents may be treated first with habit reversal, which increases awareness of hair pulling.23 Unfortunately, many young patients with trichotillomania appear to be much less motivated than their parents to undergo treatment.

Minor side effects common

Most SSRI side effects are neuropsychiatric or gastrointestinal. These side effects, which are common and relatively mild, should be monitored with an office visit every three weeks. It's also wise to warn families about the possibility of minor problems so they will be less inclined to give up too soon on the medications. Serious sequelae, discussed later, occasionally occur.

Gastrointestinal symptoms often occur early, mediated by gut receptors. Vague gastrointestinal distress, nausea, and anorexia are common and transient, and they can be minimized by taking SSRIs on a full stomach. Later in treatment, SSRIs may exert a central anorexic effect, which may be helpful in treating a patient with bulimia. In our clinical experience, few children and even fewer adolescents lose much weight on SSRIs.

Neuropsychiatric side effects cover a broad range. Sleep changes are common, including daytime sedation, insomnia, and vivid, frightening dreams. Like most antidepressants, SSRIs alter sleep architecture, decreasing total sleep time, sleep efficiency, and the duration of rapid-eye-movement sleep. Other neuropsychiatric side effects of SSRIs are headaches (most likely mediated by peripheral vascular serotonin receptors), tremor, and jitteriness.

Sexual side effects, including delayed orgasm, anorgasmia, and decreased libido, occur in about one in four adults on SSRIs. Boys may develop gynecomastia, girls mammoplasia. Always explain these potential side effects to your adolescent patients, who may discontinue their medication if they have not been adequately counseled

Choosing and prescribing an SSRI

Prescribe an SSRI only after a child has been soundly diagnosed with a disorder shown to respond to this class of medications. In most patients with mild to moderate illness, a brief trial--four to six sessions--of psychotherapy should be considered before prescribing an SSRI. Consider conferring with a child psychiatrist before prescribing an SSRI for a child of 7 or younger. Follow up any suspicion of a psychiatric disorder by collecting collateral histories from several responsible adults who know the patient, performing a complete physical examination, and assessing mental status, school performance, stressors, family dynamics, and any role transitions the child may be undergoing. Well-trained child therapists can be very helpful in making the diagnosis, and therapy may improve compliance with medication.

Order laboratory studies in patients with questionable liver, renal, or left ventricular function and children who are taking medications with narrow therapeutic indices, such as warfarin or digitalis. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) should be discontinued for at least two weeks before initiating an SSRI.

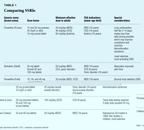

Which SSRI? One can't predict the best SSRI for a particular patient since a child who doesn't respond to one SSRI may respond to another. Table 1 compares the characteristics of various SSRIs. For each agent, the "minimum effective dose in adults" is based on the recommendation for depression cited in the manufacturer's package insert. Some physicians feel most comfortable choosing a drug on the basis of its FDA-approved indications, so these are listed in the table as well.

Titration techniques. SSRI dosing in children is poorly defined. Most published studies report dosage by mg/day, not mg/kg/day. These studies generally included children at least 7 years of age; some required a minimum weight of 20 kg for enrollment. Most side effects of SSRIs are dose-dependent. Clinicians can minimize many adverse effects with small initial doses, titrating over weeks to an initial target dose. Table 2 lists target dose ranges for children 8 years or older who weigh at least 20 kg. Allowing time for the target dose to work will minimize children's exposure to excessive doses. Four- to six-week trials are a minimum for most disorders, and eight to 12 weeks for OCD, selective mutism, and trichotillomania.

A few examples may clarify titration techniques. A 10-year-old boy with major depression that does not fully respond to six sessions of psychotherapy is started on 12.5 mg of sertraline, which is increased in 12.5 mg increments every four to seven days to an initial target dose of 50 mg/day. After four weeks on 50 mg/day, the child is free of side effects and his condition has improved, but he continues to be more tearful and sad than he was at baseline. The dose is increased to 100 mg/day, and four to six weeks later he is free of symptoms. In another example, a 9-year-old with selective mutism with limited response to psychotherapy begins taking 4 mg of fluoxetine a day, but his mother reports hyperactivity and increased anxiety that persists for 10 days. Fluoxetine is reduced to 2.5 mg for two weeks and then is titrated in 1 mg increments to 4.5 mg a day, the highest tolerated dose. The boy begins talking in situations where he had been silent outside of school and nine months later, when fluoxetine has been titrated to 10 mg/day, he begins talking at school.

The dose-response curves for SSRIs are flat in adults; the smallest effective dose-that is, the starting dose the Physicians' Desk Reference lists for adults--usually has the greatest benefit. If the patient doesn't respond at all to an adequate trial of a low dose, it is unlikely he or she will respond to higher doses. Those with some response to the initial trial may respond to a higher dose, however.

Very low initial doses are appropriate for children, younger and smaller adolescents, migraine sufferers, and anxious or medically ill patients. Patients taking other medications that, like SSRIs, are cytochrome p450 (CYP) inhibitors should also be started on quite low doses: 5 mg of fluoxetine or paroxetine, 12.5 mg of sertraline, 25 mg of fluvoxamine, or 10 mg of citalopram. While fluoxetine does not need to be taken every day, other SSRIs require at least daily dosing. CYP is a microsomal enzyme system that detoxifies many drugs.

In our clinics, parents take home SSRI titration sheets, which schedule dose increases every four to seven days to reach an initial target dose within two to three weeks, unless side effects slow the titration. Tell parents to maintain a low dose for at least a week if side effects are annoying; slow increases may minimize side effects at higher doses. Protracted minor side effects such as insomnia or nausea are often best managed by reducing the dose. Along with the titration sheet, we give parents an informed consent form and a list of side effects, remedies, and actions, including instructions on when to call the office (allergic rash) or go to the emergency room (probable serotonin syndrome or overdose). The consent form recommends keeping all medications under lock and key.

Once patients have reached the target dose, we assess them for benefit, side effects, and compliance with psychotherapy and medication. Suicidal or self-injurious thoughts, behavioral changes, sleep problems, and anxiety get particular attention, and we check height, weight, blood pressure, and pulse at each visit. We ask parents about how they administer the medication and where they are storing it.

Progress on the target dose is reassessed four to six weeks later. Patients with partial or no response may then be titrated to a higher target dose. If patients do not improve after an adequate trial, we taper the SSRI over 10 to 14 days to minimize discontinuation symptoms, such as excessive tearfulness, paresthesia, or nausea. We reassess the diagnosis, psychotherapy, and environment before considering another drug trial.

How SSRIs work

Before SSRIs were developed, tricyclics were the most-used antidepressants. While clearly effective in adults,11 small double-blind, placebo- controlled studies have failed to demonstrate that tricyclics are consistently effective against depression in children and adolescents. In addition, tricyclics, infamous for cardiac toxicity, have been common lethal agents in suicides; SSRIs are rarely fatal in a single overdose and do not have clinically significant cardiac effects, though they can be toxic.

Pharmacology and pharmacokinetics. SSRIs work, with varying selectivity, on serotonin receptors, unlike the "dirtier" tricyclics, which target many brain receptors, primarily those that are noradrenergic. In children, the serotonin system appears to be a better medication "target" than the noradrenergic system, perhaps because the child's noradrenergic system is immature. The serotonin system develops earlier. Brain serotonin falls to adult levels in preschoolers, after peaking during the second trimester of gestation. Even so, children respond to SSRIs differently than adults, as shown by the different profile of side effects in the two age groups. The reason may be that other parts of children's brain development are incomplete, or it may lie in characteristics of children's metabolism.

The five SSRIs vary significantly in their half-lives and pharmacokinetic linearity. Fluoxetine has a long half-life (two to three days), as does its active metabolite, norfluoxetine (seven to nine days). Clinically significant plasma levels persist at least five weeks after fluoxetine is discontinued, a critical issue when the child is taking other medications.

Drug interactions. All SSRIs are both metabolized by and inhibit CYP microsomal enzymes. As a patient takes larger doses of SSRIs, the inhibition of CYP enzymes, which is the most important factor in interactions between SSRIs and other drugs, increases. Patients at highest risk for clinically significant drug interactions are those using several drugs that induce or inhibit CYP isoenzymes, have a low therapeutic index, or have multiple pharmacologic actions. Drugs that are most likely to result in significant drug interactions when used with SSRIs include phenytoin, carbamazepine, digitalis, warfarin, and alprazolam.

Combining SSRIs with tricyclics is a particular concern because SSRIs greatly elevate tricyclic blood levels. Since tricyclics, especially desipramine, have been associated with sudden death in children, frequent tricyclic levels and electrocardiograms are mandatory in those few cases in which the two types of drug are used together.

Serious side effects a possibility

Some sequelae of SSRIs are much more serious than the side effects discussed above. SSRI overdoses are toxic and can lead to four neuropsychologic syndromes, summarized in Table 3. Behavioral side effects appear to be fairly common, though reported rates vary widely; the other neuropsychologic sequelae may occur in fewer than 1% of patients. Psychiatric disorders may begin or worsen as a result of taking an SSRI.

Toxicity caused by overdose. Accounts of two pediatric SSRI overdoses have been published: a toddler ingesting 250 to 300 mg of sertraline became febrile and lethargic, and an adolescent had tonic-clonic seizures and S-T segment depression after a fluoxetine overdose.

Adult SSRI-only ingestions are rarely fatal. Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms; protracted vomiting rarely causes aspiration pneumonia. Massive SSRI overdoses (more than 75 times the common daily dose) have caused seizures and EKG changes (sinus bradycardia or tachycardia, QTc prolongation, torsades des pointes); death has occurred after fluoxetine, paroxetine and citalopram ingestions at doses 150 or more times than the common daily dose.10

Serious side effects are most likely in coingestions, particularly with alcohol or when a person taking another CYP--metabolized medication ingests an SSRI as well. SSRI absorption slows markedly in overdose. Gastric lavage and activated charcoal are beneficial; charcoal is helpful up to 24 hours after the SSRI has been ingested. Cardiac and respiratory monitoring has been recommended.

Relationship to suicide. Large studies and reviews show that depressed adults treated with SSRIs are less likely to become suicidal than depressed adults treated with placebo or tricyclics. In one study, six of 42 children and adolescents with OCD on fluoxetine became suicidal; they had vivid, violent dreams and injured themselves severely enough to require hospitalization. Symptoms began one to six months after they started taking an SSRI; two patients rechallenged with fluoxetine became suicidal again.

Serotonin syndrome occasionally develops in someone taking just one serotonergic agent, though more often after two or more such agents are taken concurrently. MAOIs and SSRIs are a dangerous, contraindicated combination.

Fever, muscular rigidity, hyperreflexia, and mental status change are minimum criteria for syndrome diagnosis. Emergent treatment in an intensive care setting includes withdrawal of serotonergic agents, fever reduction, and benzodiazepines for myoclonus, rigidity, or seizures. Hyperpyrexia (temperature more than 105° F) is an ominous sign, mandating aggressive cooling, muscular paralysis, and intubation. Arterial blood gases are useful for assessing anoxia and metabolic acidosis. Patients should be monitored for rhabdomyolysis and disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Extrapyramidal symptoms result when SSRIs block dopamine, directly or indirectly, via serotonin-dopamine interactions. Akathisia (restlessness and an inability to sit still) is the most common extrapyramidal symptom, occurring in up to 45% of adults on SSRIs. Adding SSRIs or CYP inhibitors to dopamine antagonists (such as antipsychotics) has caused sudden onset or exacerbation of these symptoms.

Behavioral activation. SSRIs can cause anxiety or behavioral side effects, such as irritability, hyperactivity, or insomnia. The least selective SSRIs, which have the most reuptake inhibition at noradrenergic and dopaminergic sites, are the most activating. Fluoxetine is at the top of the list, followed by fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, and citalopram.

Children and adolescents are more likely than adults to have behavioral side effects; younger children may be most vulnerable. Assess medication compliance since symptoms overlap those of serotonin discontinuation syndrome. Reported rates range from 20% on sertraline to 50% on fluoxetine; many children respond to dose reduction.

Hypomania, mania, and psychosis have occurred in youth treated with fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline; depression or dysthymia appears to be a risk factor. Although slow dose titration is said to decrease behavioral side effects, titration of as little as 2 to 5 mg of fluoxetine a week has resulted in severe activation in adolescents.

SSRI discontinuation syndrome (SDS), a cluster of neuropsychiatric or systemic symptoms that arise after drugs have been discontinued, most often follows paroxetine discontinuation, even with a two-week taper, and is least common with longer-lasting fluoxetine. Symptoms, usually transient and mild, begin within one to three days of dose reduction of the SSRI. With fluoxetine, however, SDS is delayed to seven to 10 days; most patients are symptom free one to two weeks later. Highly distressed patients who are discontinuing a SSRI with a shorter half-life than fluoxetine may benefit from several weeks of low-dose fluoxetine.

Proceed with caution

Most studies of SSRI use in mental disorders have been conducted in adults, and we still have much to learn about their efficacy and dosage in children. Many children respond well to psychotherapy alone. Others may require SSRIs, which can be safe and effective, especially if psychotherapy is part of the management strategy.

REFERENCES

1. Birmaher B, Brent DA, The Work Group on Quality Issues: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37

(suppl 10):63

2. Emslie GJ, Rush AJ, Weinber WA, et al: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of fluoxetine in children and adolescents with depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1997;54:1031

3. Simeon JG, Dinicola VF, Ferguson HB, et al: Adolescent depression: A placebo-controlled fluoxetine study and follow-up. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1990;14:791

4. Alderman J, Wolkow R, Chung M, et al: Sertraline treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder or depression: Pharmacokinetics, tolerability, and efficacy J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37(4):386

5. Ambrosini PJ, Wagner KD, Biederman J, et al: Multicenter open-label sertraline study in adolescent outpatients with major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38(5):566

6. Boulos C, Kutcher S, Gardner D, et al: An open naturalistic trial of fluoxetine in adolescents and young adults with treatment-resistant major depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1992;2(2):103

7. Rey-Sanchez F, Gutierrez-Casares JR: Paroxetine in children with major depressive disorder: An open-trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(10):1443

8. Riddle MA, Scahill L, King RA, et al: Double-blind, crossover trial of fluoxetine and placebo in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1992;31(6):1062

9. March JS, Biederman J, Wolkow R, et al: Sertraline in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998;280(20):1752

10. Fluvoxamine, in Physicians' Desk Reference, ed 52. Montvale, NJ, Medical Economics Company, 1999

11. King RA, Leonard H, March J, et al: Practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1998;37(suppl 10):27

12. Dummit ES, Klein RG, Tancer NK, et al: Fluoxetine treatment of children with selective mutism: An open trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psych 1996;35(5):615

13. Black B, Uhde TW: Treatment of elective mutism with fluoxetine: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1994;33(7):1000

14. Fairbanks JM, Pine DS, Tancer NK, et al: Open fluoxetine treatment of mixed anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1997;7(1):17

15. Last CG, Perrin S, Hersen M, et al: A prospective study of childhood anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1996;35(11):1502

16. van der Kolk BA, Dreyfuss D, Michaels M, et al: Fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1994;55(12):517

17. Fluoxetine Bulimia Nervosa Collaborative Study Group: Fluoxetine in the treatment of bulimia nervosa: A multicenter, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:139

18. Mayer LES, Walsh BT: The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in eating disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1998;59(suppl 15):28

19. McDougle CJ, Naylor ST, Cohen DJ, et al: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of fluvoxamine in adults with autistic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:1001

20. Johnston HF, Witkovsky MT, Fruehling JJ: SSRIs: Children & adolescents. Newsletter, Univ of Wisconsin Child Psychopharmacol Info Service 1998;4(3):1

21. Findling RL: Open-label treatment of comorbid depression and attentional disorders with co-administration of serotonin reuptake inhibitors and psychostimulants in children, adolescents, and adults: a case series. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 1996;6(3):165

22. Barrickman L, Noyes R, Kuperman S, et al: Treatment of ADHD with fluoxetine: a preliminary trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1991;30(5):762

23. O'Sullivan RL, Christenson GA, Stein DJ: Pharmacotherapy of trichotillomania, in Stein DJ, Christenson GA, Hollander G (eds). Trichotillomania. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1999;93

24. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Rapoport JL: A double-blind comparison of clomipramine and desipramine in the treatment of trichotillomania (hair-pulling). N Engl J Med 1989;321:497

Additional references are available from the authors on request.

Kelda Walsh, Christopher McDougle. When SSRIs make sense. Contemporary Pediatrics 2000;1:83.