Toddler With Microcephaly, Growth Delay, and Subtle Facial Changes: What Diagnosis Besides Strabismus and Developmental Delay?

A 2-year-old girl has been followed for developmental delays and slow weight gain by her pediatrician and early childhood intervention therapists. The 17-year-old, first-time mother was also a runaway and had avoided early prenatal care. More details and questions for you, here.

A 2-year-old girl has been followed for developmental delays and slow weight gain by her pediatrician and early childhood intervention therapists. She was the product of the first pregnancy of a single mother, age 17, who had run away from home and who had avoided early prenatal care.

Ultrasonography at a later gestational stage showed a small head size, and the uncomplicated vaginal delivery yielded a normal-appearing infant with good Apgar scores. Urine drug screens from the mother and infant were negative. The infant had difficulty breastfeeding but fed well on formula. Slow weight gain was noted despite involvement of the maternal grandmother with care; the grandmother thought the infant was irritable and less responsive than her daughter and 5 other children had been.

Weight gain improved somewhat with strategies and medication for GE reflux but remained in the 3rd percentile relative to a length in the 25th percentile. At age 8 months, left esotropia was noted; this was treated with patching and glasses. Motor milestones included sitting at age 8 months and walking at 16 months. At 2 years, the child is somewhat clumsy with a wide gait. She says 2 to 3 words consistently without phrases, and is less responsive to commands than her grandmother thinks appropriate. She and the mother feel that the child’s behavior is hyperactive and impulsive.

The family history is unremarkable except for possible diagnosis of bipolar disorder in the mother and the maternal grandfather; the father’s history is unknown.

Review of systems is normal, except that the child has difficulty going to sleep and has decreased pain sensitivity.

Her height is at the 25th percentile for age, weight at the 3rd percentile, and head size below the 3rd percentile.

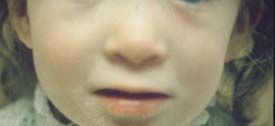

She is a quiet child who appears well-nourished, with normal subcutaneous tissue and good skin turgor. The facial appearance (Figure 1) appears normal except for a broad nasal root. Cardiac, pulmonary, and abdominal exams were unremarkable. Her palms showed a single crease bilaterally with inward curving of the fifth fingers (Figure 2). Neurologic exam revealed an irritable child with mild generalized hypotonia.

1. What diagnosis besides strabismus and developmental delay should be considered in this child?

2. Do you agree that the facial appearance in Figure 1 is normal, and if not, what changes do you see?

3. What laboratory tests might be considered?

4. Given the likely diagnosis, what preventive health care issues should be addressed?

ANSWERS (please see Discussion for further details)

1. What diagnosis besides strabismus and developmental delay should be considered in this child?

An important diagnosis to consider would be fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), which could account for the microcephaly, failure to thrive, behavior differences, strabismus, and minor anomalies (facial and hand changes). An underlying disorder should be suspected in young children with hyperactivity since true ADHD is best assessed by poor school performance.

2. Do you agree that the facial appearance in Figure 1 is normal, and if not, what changes do you see?

The photograph shows subtle facial changes (minor anomalies) that are typical of fetal alcohol syndrome-broad nasal root, absent or flat philtrum, and thin upper lip.

3. What laboratory tests might be considered?

No biochemical or molecular markers correlate with the effects of ethanol on the fetus, so the diagnosis of FAS is clinical. Chromosome studies should be considered in any child with unexplained developmental delays, particularly when the child has an unusual appearance and growth discrepancies (disproportionate weight and head size in this case). Routine chromosomes with reflex to high resolution chromosome (array-CGH or microarray) analysis should be considered since the latter technique often reveals submicroscopic aberrations in individuals with minimal dysmorphology and behavior differences (autism, mental illness, etc.). The routine and high resolution chromosome studies (reflex means proceed to the next test if the previous one is normal) can prevent inappropriate diagnoses of maternal substance abuse, especially important because mental illness or disability often underlies maternal chemical dependency and/or neglect.

4. Given the likely diagnosis, what preventive health care issues should be addressed?

Preventive health care for FAS will include alertness for cognitive and behavioral differences, strabismus, heart defects, and orthopedic anomalies such as club foot.

Figure 2-

This boy with fetal alcohol syndrome shows triangular facies, broad nasal bridge, right eye ptosis, flat philtrum, and a thin upper lip.

FETAL ALCOHOL SYNDROME: DISCUSSION

As with other malformation syndromes, FAS is first a clinical diagnosis through recognition of a malformation pattern.1-3 A smaller head size in proportion to length is suggestive as is early failure to thrive and irritability. The face often has minor anomalies including the broad nasal root, absent or flat philtrum, and thin upper lip shown in Figure 1.3 With age, the face is more triangular, with smaller eyes as shown by the child with FAS in Figure 2.

FAS is thought to be the most common syndrome at 1.5-1.7 per 1000 births in some North American regions. This may represent an underestimate because over half of mothers give no history of drinking during pregnancy.1-4 Constant rather than early binge drinking is thought more harmful: the threshold is at least 2-3 drinks daily.

Some have proposed the term fetal alcohol effects for children with typical behaviors (impulsivity, irritability) but without facial changes (exposures after the first trimester). However, the lack of objective laboratory markers makes general use of FAS or of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders preferable.1

Exercise care in making the diagnosis without maternal admission or testing because foster placement will often follow. Alcoholism and its comorbid mental illnesses have significant hereditability, further contributing to the instability of alcoholic families.2 Attention to social concerns is as important as monitoring for complications (Table) in providing preventive health care through the medical home model.4

References:

References

1. CDC. Surveillance for fetal alcohol syndrome using multiple sources-Atlanta, Georgia, 1981–1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1997;46:1118-1120. (Note: The CDC website has excellent lay and medical information- www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fasd/index.html. Accessed October 25, 2011.

2. Famy C, Streissguth AP, Unis AS. Mental illness in adults with fetal alcohol syndrome or fetal alcohol effects. Am J Psych. 2001;124:1138-1148.

3. Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, et al. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics. 2005;115:39-47.

4. Wilson GN, Cooley WC. Preventive Health Care for Children with Genetic Condition: Providing a Medical Home, 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.