A 13-year-old girl with well-demarcated rash on back and chest

A healthy 13-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of an asymptomatic, well-demarcated rash on her back and upper chest. The eruption consisted of discrete, dark brown papules that coalesced into large, flat-topped plaques with mild superficial scale and accentuation of skin markings. What's the diagnosis?

A 13-year-old girl with welldemarcated rash on back and chest | Image Credit: © Author provided - © Author provided - stock.adobe.com.

The case:

A healthy 13-year-old girl presented with a 1-month history of an asymptomatic, well-demarcated rash on her back and upper chest. The eruption consisted of discrete, dark brown papules that coalesced into large, flat-topped plaques with mild superficial scale and accentuation of skin markings (Figure). The skin findings displayed a reticulated pattern and first appeared on her central back before spreading centrifugally. She denied any systemic symptoms; history of similar eruptions; and exposure to new soaps, deodorants, fragrances, detergents, clothing, or other known potential allergic triggers. Her vital signs and weight were normal for her age, her mucosal surfaces and nails were normal, and there was no involvement of the skin on the palms or soles. The patient ate a regular diet, was not sexually active, and did not use heating pads or space heaters. There was no family history of autoimmune or other illnesses. She took no prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, or supplements. Potassium hydroxide exam of the superficial scale was negative.

Diagnosis and clinical findings:

CARP is a rare, chronic dermatosis caused by an alteration in keratinocyte differentiation.1 Early lesions may be erythematous but will typically become hyperpigmented, scaly macules or papillomatous papules that coalesce into confluent patches or plaques centrally while exhibiting a reticular pattern peripherally.2 The typical distribution of lesions is on the trunk, axilla, and neck, though cases have been reported involving the shoulders, arms, and antecubital and popliteal fossae.2 Lesions of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis are normally without systemic symptoms; however, a small number of patients report pruritis.2 The disease has a mean duration of 3.1 years and may range from 3 months to 20 years without treatment and occasionally recurs.3

Epidemiology/pathophysiology:

CARP usually affects adolescents and young adults with most studies reporting an average age of incidence between 15 and 17 years, although 1 study reported an average age of incidence of 29.1 years.4,5 Two recent cohort studies further support the younger age of incidence, with ages of diagnosis of 13.8 years and 14.6 years, respectively.6,7 There is a slight predilection in males historically, though this is not well-established as the literature contains conflicting reports of a female preponderance or no variation in the condition with sex.1,6,7 Although evidence supports the etiology of CARP to be an alteration in keratinocyte differentiation, the underlying pathogenesis has not been definitively established.1 Hypotheses of the pathogenesis of CARP include infection with Dietzia papillomatosis, keratin-16 mutations, an abnormal response to Malassezia furfur, elevated insulin levels, ultraviolet radiation exposure, or cutaneous deposition of amyloid.1 Results of a study of 111 children with CARP showed an elevation of serum insulin levels in more than half of the patients, as well as an 88% rate in patients who were obese or overweight. Results of a second study of 68 children reported 91% of patients were obese or overweight.6,7 These findings support glucose dysmetabolism as a potential etiology, with a proposed mechanism of insulinlike growth factor 1 activating receptors on keratinocytes and fibroblasts to promote cell growth and differentiation.6,7 These findings surrounding an endocrine etiology also suggest there may also be an overlap between CARP and acanthosis nigricans.

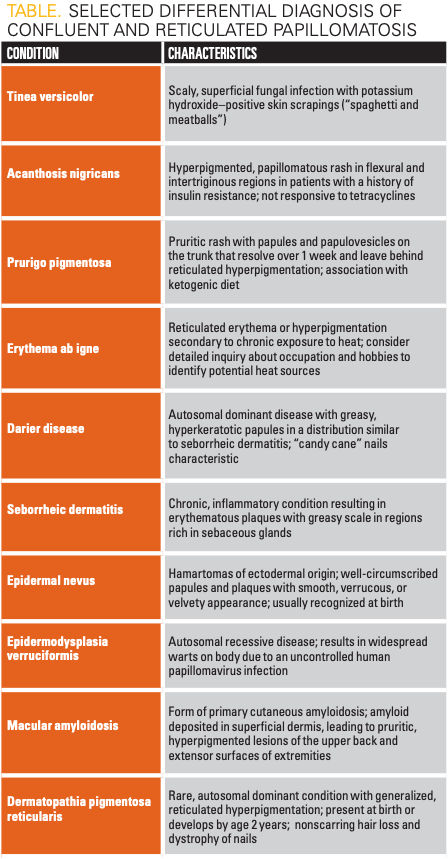

Differential diagnosis:

The differential diagnosis of an eruption with hyperpigmented, coalescing papules and plaques in a reticulated pattern is broad (Table). One condition to consider is pityriasis versicolor—also called tinea versicolor—which is a common superficial fungal infection caused by Malassezia spp.8 Classic findings in pityriasis versicolor include superficial, minimally scaly, hyperpigmented, hypopigmented, and/or erythematous macules, patches, and plaques on the upper trunk, arms, or neck.8 A fine scale is often present. The condition is exacerbated by heat, humidity, oral contraceptives, and steroid use. The rash is rarely symptomatic, and potassium hydroxide preparation will reveal long hyphae and clusters of yeast cells sometimes described as “spaghetti and meatballs.”8

Secondary syphilis is caused by hematogenous dissemination of the spirochete Treponema pallidum and causes various clinical symptoms 3 to 10 weeks after a primary chancre.9 The cutaneous eruption of secondary syphilis is typically a psoriasiform eruption that is diffusely and symmetrically distributed on the trunk and extremities.9 Lesions are often scaly and may be red, violet, or copper colored.9 Involvement of the palms and soles should raise suspicion for secondary syphilis, and a detailed sexual history should be obtained.

Acanthosis nigricans classically presents in flexural and intertriginous regions, often involving the neck folds and axillae.10 Skin findings include hyperpigmented plaques with a velvety, verrucous, or papillomatous appearance.10 Patients may have a history of obesity, endocrine disorders (particularly diabetes or polycystic ovarian syndrome), malignancy, or medications that promote elevated levels of insulin.10 On histology, acanthosis nigricans tends to show a greater degree of pigmentation and melanocytic proliferation than CARP; however, there may be overlapping presentations of CARP with acanthosis nigricans. If the diagnosis is in question, CARP may be differentiated from acanthosis nigricans by its high response rate to tetracycline antibiotics.

Seborrheic dermatitis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects areas of the body rich in sebaceous glands.11 The pathogenesis is believed to be related to an abnormal immune response to Malassezia yeast. The scalp, eyebrows, glabella, nasolabial folds, beard area, and trunk are common locations.11 Findings in seborrheic dermatitis include erythematous, well-demarcated plaques with a greasy scale.11

Prurigo pigmentosa is an idiopathic condition affecting young adults, typically women, and presents with pruritic papules and papulovesicles predominantly on the back, neck, and chest.12 Lesions often resolve within a week and leave regions of macular, reticulated hyperpigmentation.12 Recurrences tend to occur on previously involved skin sites, and prurigo pigmentosa has been reported to be associated with a ketogenic diet.13

Erythema ab igne is a localized finding resulting from chronic exposure to heat or infrared radiation that is not intense enough to cause thermal burns.12 Common heat sources include laptops, space heaters, heating pads, and radiators.12 The rash is asymptomatic and reticulated, corresponds to the venous plexus of the affected area, and may be erythematous or hyperpigmented.14 Notably, there is no associated scale.

Evaluation/workup:

Diagnosis of CARP is clinical because there are no pathognomonic histologic findings. However, papillomatosis, an undulating basket-weave hyperkeratosis, focal acanthosis, or an increase in basal melanin pigmentation may be observed.1 Evaluation of scales from skin scrapings with potassium hydroxide will aid in ruling out common fungal conditions. Revised diagnostic criteria for CARP were published in 2014.15 The 4 criteria proposed were: (1) scaly brown macules and patches, with at least some appearing reticulated and papillomatous; (2) involvement of the upper trunk, neck, or flexural areas; (3) negative fungal staining of scales or no response to antifungal treatment; and (4) excellent response to antibiotics.15 To prevent a delay in diagnosis and treatment, CARP should be considered for eruptions that resemble tinea versicolor but have a negative potassium hydroxide preparation.2 Given the association of CARP with obesity and elevated serum insulin levels, careful attention should be paid to risk factors for metabolic syndrome or other endocrine comorbidities.6,7

Treatment and management:

Tetracyclines are the most commonly prescribed class of medication for CARP and achieve complete resolution in 59.7% of cases after an average of 51.8 days.16 Minocycline 50 to 100 mg twice a day for at least 6 weeks is the most frequently used therapy and has a success rate of 61.4%.2,16 The response rate to tetracyclines is higher in pediatric patients, with 90% of patients responding with 4 to 16 weeks of minocycline or doxycycline.6 The responsiveness of CARP to tetracycline antibiotics is thought to be secondary to the anti-inflammatory action of these medications rather than the antibacterial action.6 Other antibiotics, specifically amoxicillin and azithromycin, have been prescribed in a smaller number of cases with good results.16 Successful treatment with topical retinoids, calcineurin inhibitors, vitamin D derivatives, and keratolytic agents have also been reported in the literature.16-19 Recurrence was previously reported to be 15%, but more recent studies of the pediatric population suggest CARP may recur in up to 49% of young patients within 1 to 2 years following their first treatment.2,6

Patient course: The patient was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 8 weeks. She experienced complete resolution of the rash and did not experience any adverse effects such as sun sensitivity or gastrointestinal upset during her treatment course. The patient was seen in a follow-up visit 2 months later and had not experienced any recurrence.

Lessons for clinicians:

- Know the characteristic features of CARP to expedite diagnosis and avoid invasive procedures.

- Consider performing skin scraping with potassium hydroxide examination for any condition with superficial scale to aid in the diagnosis of common conditions such as tinea versicolor or tinea corporis.

- Understand that erythema may be difficult to appreciate in patients with skin of color because it may present with a violet color or hyperpigmentation. A detailed history of any rash that includes initial presentation, evolution, morphology, symptoms, and history of medication or other exposures may help rule out conditions that may be difficult to diagnose in skin of color.

- Consider having any patient with cutaneous concerns don a gown to aid in evaluating the extent of a skin condition and identification of asymptomatic lesions unknown to a patient.

Click here for more from the October 2023 issue of Contemporary Pediatrics®.

References:

1. Lim JHL, Tey HL, Chong WS. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:217-223. doi:10.2147/CCID.S92051

2. Le C, Bedocs PM. Confluent and Reticulated Papillomatosis. In: StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing; 2021. Accessed September 1, 2023. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29083642/

3. Davis MDP, Weenig RH, Camilleri MJ. Confluent and reticulate papillomatosis (Gougerot-Carteaud syndrome): a minocycline-responsive dermatosis without evidence for yeast in pathogenesis. A study of 39 patients and a proposal of diagnostic criteria. Br J Dermatol. 2006;154(2):287-293. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06955.x

4. Lim JHL, Tey HL, Chong WS. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:217-223. doi:10.2147/CCID.S92051

5. Huang W, Ong G, Chong WS. Clinicopathological and diagnostic characterization of confluent and reticulate papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud: a retrospective study in a South-East Asian population. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16(2):131-136. doi:10.1007/s40257-014-0110-8

6. Xiao TL, Duan GY, Stein SL. Retrospective review of confluent and reticulated papillomatosis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Dermatol. 2021;38(5):1202-1209. doi:10.1111/pde.14806

7. McKenzie PL, Ogwumike E, Agim NG. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis in pediatric patients at an urban tertiary care center. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39(4):574-577. doi:10.1111/pde.15023

8. Gupta AK, Batra R, Bluhm R, Faergemann J. Pityriasis versicolor. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21(3):413-429. doi:10.1016/s0733-8635(03)00039-1

9. Balagula Y, Mattei PL, Wisco OJ, Erdag G, Chien AL. The great imitator revisited: the spectrum of atypical cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(12):1434-1441. doi:10.1111/ijd.12518

10. Das A, Datta D, Kassir M, et al. Acanthosis nigricans: a review. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;19(8):1857-1865. doi:10.1111/jocd.13544

11. Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(3):185-190

12. Chang, MW. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. In: Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2018:1551.

13. Oba MC, Arican CD. Clinical features and follow-up of prurigo pigmentosa: a case series. Cureus. 2022;14(4):e24600. doi:10.7759/cureus.24600

14. Kettelhut EA, Traylor J, Sathe NC, Roach JP. Erythema Ab Igne. In: StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Accessed September 1, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538250/

15. Jo S, Park HS, Cho S, Yoon HS. Updated diagnosis criteria for confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a case report. Ann Dermatol. 2014;26(3):409-410. doi:10.5021/ad.2014.26.3.409

16. Mufti A, Sachdeva M, Maliyar K, et al. Treatment outcomes in confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):825-829. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.08.133

17. Bowman PH, Davis LS. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: response to tazarotene. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48(suppl 5):S80-S81. doi:10.1067/mjd.2003.155

18. Kägi MK, Trüeb R, Wüthrich B, Burg G. Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis associated with atopy. Successful treatment with topical urea and tretinoin. Br J Dermatol. 1996;134(2):381-382. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1996.tb07644.x

19. Tirado-Sánchez A, Ponce-Olivera RM. Tacrolimus in confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot Carteaud. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52(4):513-514. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.04927.x

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.