Breath-holding spells: Scary but not serious

Understanding the characteristics of breath-holding spells and how to differentiate them from serious conditions will help you reassure parents so they can better deal with these alarming but benign episodes.

Breath-holding spells: Scary but not serious

By Jane E. Anderson, MD, and Daniel Bluestone, MD

Understanding the characteristics of breath-holding spells and how to differentiate them from serious conditions will help you reassure parents so they can better deal with these alarming but benign episodes.

A frightened mother runs into your office carrying her 15-month-old, who has just had a "blue spell." Your nurse notes that the girl is comfortable and alert and calmly escorts the mother into an exam room. The mother says that the attack occurred while she was preparing dinner and her daughter was playing in the living room. Suddenly, the mother heard a cry and a thud, and rushed to the living room to see her daughter lying on the floor beside the couch, apparently not breathing, her lips blue. The mother picked up the child, who appeared stiff, and began mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The child responded rapidly, taking a big breath, and gradually woke up. The mother then rushed to your office.

This scenario is typical of the breath-holding spells that up to 5% of children have.1 Though the spells themselves are self-limited and harmless, the differential diagnosis includes more serious diseases such as epilepsy. Thus, it is important to recognize the characteristic features of breath-holding spells, distinguish them from other problems, and know how to calm parents' fears.

Typical sequence

Breath-holding spells follow a stereotyped sequence. The spell is provoked by something that causes anger, frustration, pain, or surprise, quickly followed by crying. The child then becomes quiet, exhales, and stops breathing. His color changes quickly (he becomes pale or cyanotic). Finally, he loses consciousness and becomes stiff or, less often, limp. If the child doesn't breathe for 10 seconds or longer, opisthotonic posturing with or without clonic movements may occur and the child becomes limp. He returns to consciousness fairly rapidly, remaining drowsy only briefly before resuming normal activity. From start to finish the usual breath-holding spell lasts from two to 20 seconds. The spells are totally involuntary since the breath is held after exhalation, not after inhalation.

This scenario varies slightly, depending on which of two types of breath-holding spells the child has.

Cyanotic, or type 1, spells are usually precipitated by an event that makes the child frustrated or angry. The child cries vigorously and quickly develops apnea and cyanosis. She may have opisthotonus, lose consciousness, and go limp.

Pallid, or type 2, spells are more often provoked by a sudden, unexpected event that frightens the child, such as a bump to the head or an immunization. The child cries only a little, becomes pale and limp, and may posture or show convulsive movements before regaining consciousness. These spells are sometimes called "white breath-holding," "reflex anoxic seizures," or "infantile syncope."

In a large prospective series, 62% of children had the cyanotic type of spells and 19% had the pallid type; 19% of children had spells with features suggesting both types.1 Breath-holding spells can also be classified as "simple" if the child only loses consciousness or "severe" when seizure activity follows.

Who gets spells and how often?

The child with a family history of breath-holding spells may be at higher risk of having spells than other children, perhaps because of an underlying genetic predisposition.1,2 Most children who have breath-holding spells have the first spell between 6 and 18 months of age. Breath-holding spells that begin at a younger or older age than is customary call for special attention. In the neonatal period, when spells may start during feeding and diaper changing,1,3 breath-holding spells are a diagnosis of exclusion, calling for an extensive workup to eliminate major central nervous system, cardiac, respiratory, and metabolic causes of cyanotic spells. Similarly, since there are no documented cases of children having first breath-holding spells at 41/2 years of age or older, a child whose spells begin this late must be carefully evaluated for posterior fossa tumor, acute hydrocephalus, epilepsy, and cardiac arrhythmias.

An individual child may have breath-holding spells once a year or many times in a single day. One third of affected children have two to five spells each day, while another third have only one a month. In most children, the spells peak between one and two years of age and then gradually become less frequent. The incidence in girls and boys is similar, though some studies show a predominance of boys.

Studies from the 1960s show that children with behavioral problems such as stubbornness, disobedience, aggression, temper tantrums, head banging, kyperkinesia, hypersensitivity, or enuresis are more likely to have breath-holding spells than other children.1,3 Keep in mind, however, that parents' perception that the breath-holding spells are part of a spectrum of bad behaviors may color their reports, and that breath-holding spells often start during a time when children are displaying negativity and oppositional behavior to demonstrate their independence. A newer, prospective study of children using the Child Behavior Checklist and Profile found no significant behavioral differences between children with breath-holding spells and controls, and no correlation between the frequency of breath-holding and scores on the behavior profile.4

Pathophysiology not well understood

Breath-holding spells represent an interplay among the central nervous system respiratory control center, the autonomic nervous system, and cardiopulmonary mechanics. In 1943, researchers showed that maneuvers that stimulate the vagus nerve, such as valsalva, slowed the pulse more in children with breath-holding spells than in other children, often to the point of asystole and hypoxic seizure activity. Further, children with pallid spells were more likely than those with cyanotic spells to have asystole.1,5 Additional research led investigators to conclude that children who have pallid spells have a more intense cardiac response to vagal stimulation than other children.5,6 The pathophysiology of cyanotic spells is more difficult to explain, but a major feature appears to be hyperventilation followed by a valsalva maneuver that reduces blood return to the heart, decreasing cerebral blood flow.

Breath-holding spells may also be caused by autonomic regulatory dysfunction. In children with pallid spells, drops in systolic blood pressure on standing have been found to be greater than in other children.7 Patients with cyanotic spells have significantly greater increases in pulse rate than other individuals when they move from a lying to a standing position and a greater decrease in diastolic blood pressure.8

Although the exact physiologic mechanism of breath-holding spells is not well understood, it is clear that children with breath-holding spells respond differently to negative stimuli than other children. Be sure to emphasize the involuntary nature of these episodes during discussions with parents.

Iron deficiency and breath-holding spells

The contribution of anemia to breath-holding spells is controversial. Investigators first noted in 1963 that children with severe breath-holding spells had lower hemoglobin levels than controls.9 Later studies showed that when children with breath-holding spells are treated for anemia, the number of spells decreases.1,1013 Treatment does not decrease spells in all children who are anemic; interestingly, however, treatment with iron can decrease the number of spells in children who are not anemic.12 A case report of an 8-month-old child who had a one-month history of pallid spells before being diagnosed with transient erythroblastopenia of childhood describes how breath-holding spells completely resolved after the child was treated with iron--even before his hemoglobin level rose.14

Some observers speculate that children with anemia have decreased cerebral oxygenation and therefore are more susceptible to breath-holding spells than children who are not anemic. Another explanation for the relationship between anemia and spells lies in the importance of iron for catecholamine metabolism and neurotransmitter activity. According to this theory, children who have spells have decreased iron stores because of an interaction between erythropoeitin receptor, which increases during cerebral hypoxia, and later erythropoiesis.15

Rule out other conditions

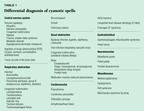

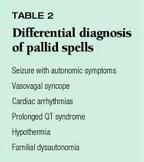

The most common entity in the differential diagnosis of both cyanotic and pallid breath-holding spells is epilepsy. Most conditions in the differential diagnosis of cyanotic spells, listed in Table 1, can easily be eliminated with an accurate history and physical examination. For pallid spells, the differential diagnosis, listed in Table 2, is primarily syncope in addition to epilepsy.5

Epilepsy. Table 3 shows how to differentiate breath-holding spells from epilepsy; when the child has a head injury, give more consideration to possible seizures. An EEG is not typically part of the workup for breath-holding spells, unless clinical findings suggest epilepsy. Between episodes of breath holding, EEGs are normal in 88% of children who have spells. An abnormal EEG does not imply that the diagnosis of breath-holding spells is incorrect, just as a normal EEG does not exclude the possibility of epilepsy.

Prolonged QT syndrome has been associated with both pallid and cyanotic breath-holding spells. In children with this syndrome, spells are most often precipitated by exercise or excitement rather than by frustration or fright, so a child whose spells start this way should have an EKG that is examined carefully for prolongation of the QT interval. Because of the seriousness of this diagnosis, some physicians recommend that all children with breath-holding spells have a baseline EKG.16

Münchausen syndrome by proxy, an unusual diagnosis, is suggested if a parent reports recurrent unwitnessed neurologic episodes and seems to be "physician shopping."

In a patient with a normal neurologic examination and a classic history for breath-holding spells whose episodes have been carefully observed, the diagnosis is usually clear. Since parents may not recognize the precipitating event or note the changes in the child's skin color, asking them to videotape an episode may allow a more detailed evaluation of the event. The only diagnostic tests to consider are an EKG to rule out prolonged QT interval and a complete blood count with serum ferritin to look for iron deficiency. An atypical history or a neurologic examination that is not completely normal warrants further diagnostic evaluation.

The long view

In about half of children with breath-holding spells, the episodes resolve by age 5 years. By the age of 6, 90% of these children no longer have spells, and by the age of 712 none of them do.1,3 This holds true for cyanotic and pallid spells.

Despite EEG changes associated with hypoxia, children who have breath-holding spells are not at risk for central nervous system sequelae. Nor are they any more likely than other children to be mentally retarded or to have epilepsy. Syncope is more common in patients who have a history of breath-holding spells, however. Children do not die from breath-holding spells, though this is what parents fear. The single case report of a death associated with a spell describes a child who had been "resuscitated" with vigorous lung compressions while lying on his stomach, a position that is no longer recommended for these maneuvers. The patient probably died from aspiration.17

Thus, children who have breath- holding spells do not have higher rates of serious morbidity or mortality than other children. Make this clear when you talk with parents. The accompanying parent guide offers further comfort about the benign nature of these spells.

Treatment largely reassurance

Watching a child stop breathing and turn blue without taking any sort of action is difficult enough for a pediatrician; imagine how impossible it must seem to a parent. Most caregivers feel they have to do something, and interventions have included turning the child upside down, splashing the child's face with cold water, and instituting cardiopulmonary resuscitation. That the child promptly begins breathing again often convinces the parents that their efforts were successful.

The most important aspect of treatment, then, is to reassure the family that the episodes are harmless. Parents need to know that the episodes are involuntary and that the child will begin breathing spontaneously without parental action. There are ways parents can help, though.

Home management. Parents can aid a child who is having an episode by making sure she is in a safe place and position. Tell them to lay the child on her back, ideally on a padded surface such as a carpeted floor. The horizontal position was shown many years ago to improve cerebral circulation.18 New research data confirm that neurocardiogenic syncope, asystole, and cerebral ischemia may be prolonged if a child remains upright,7 and the same effects might occur in children with breath-holding spells.

After taking this step a parent who is unable to observe the spell without intervening may need to leave the room. Be sure parents understand that leaving is not dangerous and that over-reacting can be.

Children whose cyanotic spells are precipitated by frustration may appear to be manipulating their parents since the child's episodes arise when his parents say No. Parents of such a child may find it hard to set limits. Let them know that children who react to frustration with breath-holding need well- defined limits even more than other children do. Once they learn the rules, they will experience less frustration and cry less often than they did when limits were unclear, thereby initiating fewer breath-holding episodes. A good illustration of this concept, with which parents can easily identify, is what happens when infants between 6 and 12 months of age fuss and fret when they are put in a car seat. If the parents are consistent in insisting on the car seat, the infant stops rebelling and is content to sit in it.

Medical management. A therapeutic trial of iron is appropriate in children who have breath-holding spells. We suggest 6 mg/kg/day for at least three months. Most physicians believe that anti-convulsants are not beneficial. Because of the apparent association of breath-holding spells with autonomic dysregulation, however, atropine may be helpful. It should be used only for severe and frequent pallid attacks in consultation with a neurologist or cardiologist.

Helping parents cope

"How can my child be normal if he sometimes stops breathing and turns blue?" Pediatricians may find it difficult to convince parents that the child who has breath-holding spells is healthy and does not require extensive diagnostic tests or that the spells are involuntary. Parents may seek a second opinion, looking for a different diagnosis or alternative treatment. By understanding the characteristics of breath-holding spells and how to differentiate them from more serious disease, pediatricians can reassure parents that their child is perfectly normal and keep them from labeling their child "bad" or "vulnerable."

DR. ANDERSON is Associate Clinical Professor of Pediatrics at the UCSF/ Mount Zion Medical Center, San Francisco.

DR. BLUESTONE is Assistant Clinical Professor of Pediatrics and Neurology, University of California, San Francisco.

REFERENCES

1. Lombroso C, Lerman P: "Breathholding Spells (Cyanotic and Pallid Infantile Syncope). Pediatrics 1967;39:563

2. DiMario F, Sarfarazi M: Family pedigree analysis of children with severe breath-holding spells. J Pediatrics 1997; 30:647

3. Laxdal T, Gomez M, Reiher J: Cyanotic and pallid syncopal attacks in children (breath-holding spells). Develop Med Child Neurol 1969;11:755

4. DiMario F, Burleson J: Behavior profile of children with severe breath-holding spells. J Pediatrics 1993;122:488

5. Stephenson JBP: Reflex anoxic seizures ("white breath-holding"): nonepileptic vagal attacks. Arch Dis Child 1978;53:193

6. Gastaut H, Gastaut Y: Electroencephalographic and clinical study of anoxic convulsions in children. Electroenceph Clin Neurophysiol 1958;l0:607

7. DiMario F, Chee C, Berman P: Pallid breath-holding spells--evaluation of the autonomic nervous system. Clinical Pediatrics 1990;29:17

8. DiMario FJ Jr, Burleson JA: Autonomic Nervous system function in severe breath-holding spells. Pediatric Neurology 1993;9:268

9. Holowach J, Thurston D: Breath-holding spells and anemia. N Engl J Med 1963;268:21

10. Bhatia MS, Singhal PK, Dhar NK, et al: Breath-holding spells: An analysis of 50 cases. Indian Pediatrics 1990;27:1073

11. Colina K, Abelson H: Resolution of breath-holding spells with treatment of concomitant anemia. J Pediatrics 1995;126:395

12. Daoud A, Batieha A, Al-Sheyyab M, et al: Effectiveness of iron therapy on breath-holding spells. J Pediatrics 1997;130:547

13. Mocan H, Yildiran A, Orhan F, et al: Breath holding spells in 91 children and response to treatment with iron. Arch Dis Child 1999;81(3):261

14. Tam D, Rash F: Breath-holding spells in a patient with transient erythroblastopenia of childhood. J Pediatrics 1997;130:651

15. Mocan H, Aslan Y, Erduran E: Iron therapy in breath-holding spells and cerebral erythropoietin. J Pediatrics 1998;133: 583.

16. Breningstall G: Breath-holding spells. Pediatric Neurol 1996;14:91

17. Paulson G: Breath-holding spells: A fatal case. Devel Med Child Neurol 1963;5:246

18. Bridge E, Livingston S, Tietze C: Breath-holding spells: Their relationship to syncope, convulsions, and other phenomena. J Pediatrics 1943;23:529

GUIDE FOR PARENTS

The child who has breath-holding spells

The problem

About 5% of young children have breath-holding spells. These involuntary spells follow an event such as falling down or being frightened, frustrated, or angry. They usually start when an infant is between 6 and 18 months of age and disappear by 5 or 6 years. They may happen once or twice a day, or once or twice a month. They are not dangerous and have nothing to do with epilepsy.

Immediately after an upsetting event, the child gives out one or two long cries. He then holds his breath after exhaling until his lips become bluish and he passes out. (Holding one's breath when frustrated and turning red without passing out is common and not considered abnormal.) One third of these children also have a few muscle twitches or jerks during some of the attacks. The child is usually breathing normally and is fully alert less than one minute after a breath-holding spell.

The solution

Treatment during spells of breath-holding. These spells are harmless and always stop by themselves. Time a few spells using a watch with a second hand, since it's difficult to estimate the length of an attack accurately. Make sure the child is lying flat on his back to increase blood flow to the head (this position may also prevent some muscle jerking). Don't start resuscitation--it's unnecessary. Also, don't put anything in your child's mouth; it could cause choking or vomiting.

Treatment after a breath-holding spell. When the spell is over, give your child a brief hug and go about your business. A relaxed attitude is best. If you are frightened, don't let your child know it. If your child had a temper tantrum before the spell because he wanted his way, don't give in to him after the spell.

Prevention of breath-holding spells. Spells that result from a fall or a sudden fright can't be prevented. Most spells that are triggered by anger also are involuntary. If your child is older than 2 years and is having daily spells, however, he probably has learned to trigger some of them himself. This often happens when parents run to the child and pick him up every time he starts to cry or give him his way as soon as the spell is over. If you avoid these responses, your child won't have an undue number of spells.

Call our office now if:

- Your child holds his breath for more than one minute (by the clock) or his spells are different from those described here.

Call our office during regular hours if:

- Your child becomes pale rather than bluish during attacks.

- Muscle jerks occur during the attack.

- Your child is a picky eater and could be iron deficient (a condition that may be associated with breath-holding spells).

- Your child has more than one spell per week (so that we can help you prevent them from becoming more frequent).

- You have other questions or concerns about breath-holding.

Adapted from Schmitt BD: Your Child's Health, ed 2. New York, NY, Bantam Books, 1999

Jane Anderson. Breath-holding spells: Scary but not serious. Contemporary Pediatrics 2000;1:61.