Changing the RSV prevention landscape

From a virus that had no treatment options, to one that may be prevented in two different modalities, clinicians are hoping to see a reduction in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) incidence rates, starting this fall.

Changing the RSV prevention landscape

This short series on RSV is a collaboration between Contagion, Contemporary Pediatrics, and Contemporary OB/GYN. Check back every week for additional stories and interviews with clinicians and key RSV stakeholders.

When first discovered in 1956, RSV was initially seen as a virus that affected chimpanzees. They isolated the virus and discovered it caused illness in young children, thus the discovery of RSV. Investigators named it respiratory syncytial virus to indicate its clinical and laboratory manifestations.1

For parents who have had their young infant admitted to the hospital with RSV, it can be a traumatic experience. The young baby might be coughing uncontrollably or having periods where he or she is crying and is inconsolable. New parents might want to hold their sick child and the baby might be hooked up to machines and cannot be held.

To date, there have been no treatments for clinicians to administer to these youngest of patients, and clinical care is more about keeping the young patients comfortable until they emerge from the acute stage of the illness.

“The treatment is mostly supportive,” Octavio Ramilo, MD, chair, Department of Infectious Diseases, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital said of caring for infants with RSV. "We provide oxygen to the baby; if the baby cannot take enough breast milk or bottle we support with IV fluids, and we suction the secretions.”

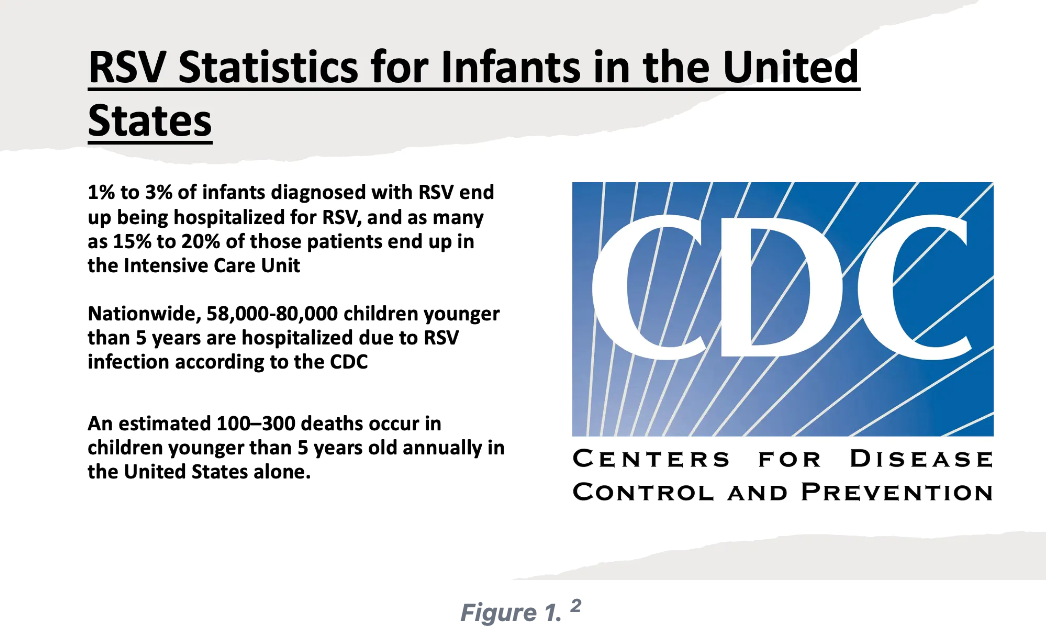

In addition, RSV continues to be the number 1 reason infants are hospitalized in the United States (Figure 1).2

The RSV Pipeline Comes to Life

In the absence of treatment, there has been a clearly defined clinical need to find ways to prevent the virus; yet up until recently, no vaccines or products have been FDA approved.

This year has witnessed great movement and accomplishments in RSV. The FDA approved a maternal vaccine (RSVpreF, Pfizer) and a monoclonal antibody, Nirsevimab-alip, (Sanofi, AstraZeneca) this summer.

Moderna also has an RSV vaccine program. Currently the program is studying the use of its investigational RSV vaccine, mRNA-1345, to prevent RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease in adults 60 years and older.

And the company recently announced key regulatory submissions for the vaccine. Although the vaccine is being studied for the senior population, Moderna has said its messenger RNA technology has the ability to pivot to other areas of need. One could see the company looking at preventing RSV in the pediatric population as well.

There is also the monoclonal antibody, palivizumab (Synagis, Sobi), which is a prophylactic RSV product available for only high-risk infants.

With the challenging RSV season last year, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supported the use of palivizumab in eligible infants. "For regions that began administering palivizumab in the summer and fall of 2022, the current widespread and intense RSV circulation may lead to a period of disease activity lasting more than the typical 6-month duration," they wrote in their guidance.3

However, its efficacy and expense has been indicated as potential challenges. Specifically, it has been reported to prevent RSV infant hospitalizations by 40%–80%, and it is also said to be cost-prohibitive, costing thousands of dollars per dose.4

The Hope Ahead

Ramilo says we are in the “Renaissance” with RSV prevention now after so many years of trying to understand and treat it—without any tools. He is optimistic there will be a reduction in RSV cases when product uptake occurs and families and clinicians are up-to-speed on these new options.

“The studies already hint that we will see a reduction in all-cause hospitalization, or all-cause pneumonia,” Ramilo said. “And this is very important.”

He also points to potentially improving people's health over lifespans. "Everything we do to prevent disease in childhood has a huge impact long term," Ramilo said. "For instance, there is data that people who have pneumonia in the first year of life have chronic lung disease when they're 70. So, anything that we can do to prevent these diseases, and RSV is one of the big ones, [we should do] to prevent these lung infections in life."

Watch this interview with Ramilo as he offers his insights on the latest products and what he hopes will be their very real benefits.

Editor’s note: The interview was conducted before the approval of the Pfizer maternal vaccine.

To learn more about women’s health, go to Contemporary OB/GYN; to learn more about pediatric health go to Contemporary Pediatrics; and to learn more about infectious disease, go to Contagion.

This article was initially published by Contagion.

References

1. Walsh EE, Hall CB. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 2015;1948-1960.e3. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4557-4801-3.00160-0

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Alert Network (HAN): increased interseasonal respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) activity in parts of the southern United States.https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2021/han00443.asp#:~:text=Each%20year%20in%20the%20United,aged%2065%20years%20or%20older. Accessed August 31, 2023

3. Updated Guidance: Use of Palivizumab Prophylaxis to Prevent Hospitalization From Severe Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection During the 2022-2023 RSV Season. AAP. Updated November 17, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2023.

4.Duong D. What RSV interventions are in the research pipeline?. CMAJ. 2023;195(1):E19-E20. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1096031

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.

Overview of biologic drugs in children and adolescents

March 10th 2025A presentation at the 46th National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) conference explored the role of biologics in pediatric care, their applications in various conditions, and safety considerations for clinicians.