Climate change: Challenges faced by the pediatric population

The World Bank Group reports that as this global health emergency escalates, devastating impacts on health and well-being will also accelerate.

Climate change: Challenges faced by the pediatric population | Image Credit: © AdobeStock_412326933 - © AdobeStock_412326933 - stock.adobe.com.

All aspects of health are affected by climate change, from clean air, water, and soil to food systems and livelihoods.1 Urgent action on the health impact of climate change is crucial to avoid increasing exposure to threats affecting the health and well-being of all, especially the pediatric population. The World Bank Group reports that as this global health emergency escalates, devastating impacts on health and well-being will also accelerate, particularly impacting children and other vulnerable populations, including women, minority groups, individuals with preexisting health conditions, and those living in poverty.2

This article aims to explore the multiple health effects of climate change on the pediatric population and the approaches pediatric nurses can employ to guide children and their caretakers to prevent negative outcomes from this public health crisis.

The significance of the problem

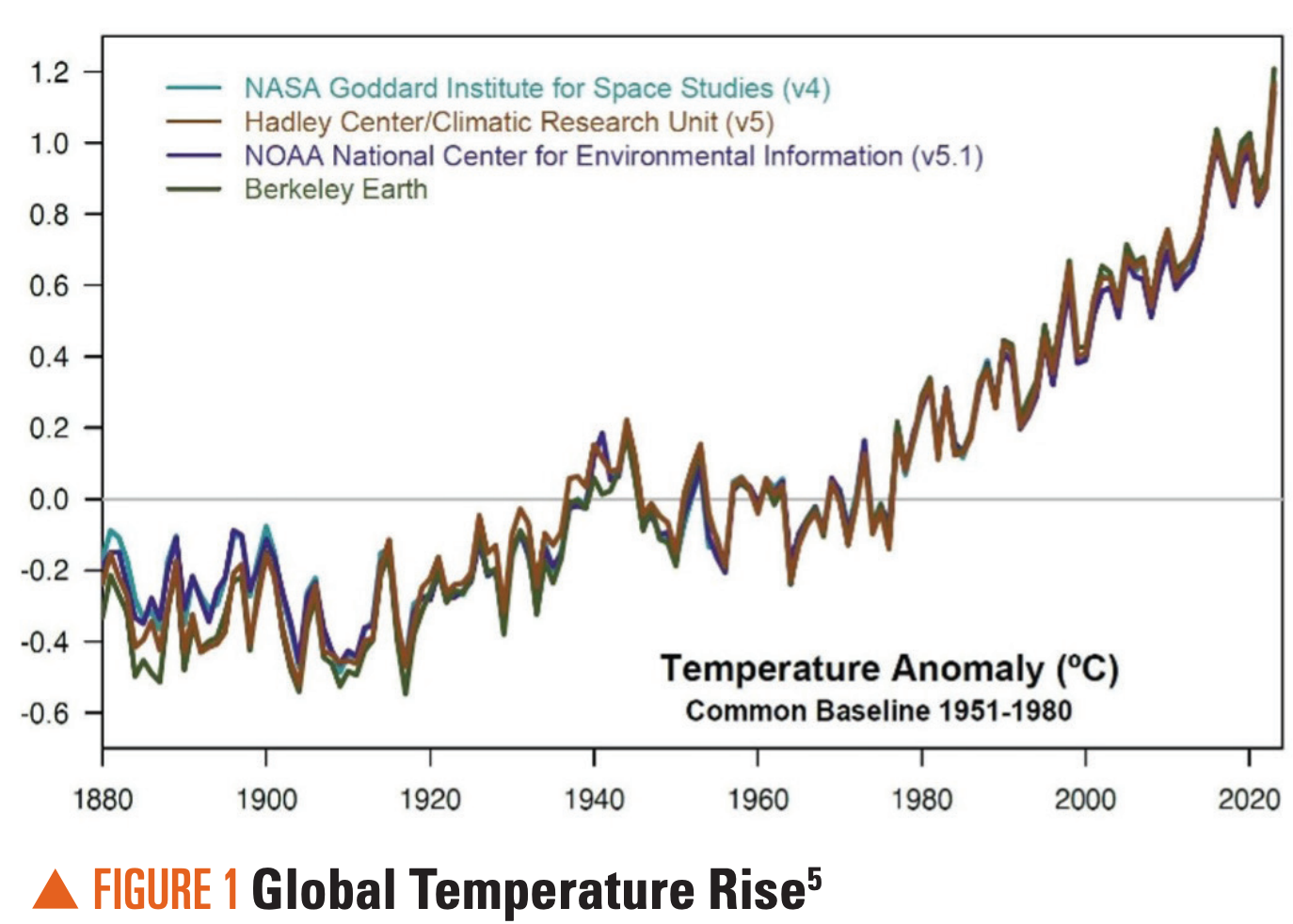

Climate change pertains to long-standing shifts in temperatures and weather patterns, which can occur naturally over extended periods of time.3 However, there has been a significant exacerbation of ecological damage resulting in rampant extreme weather events causing dangerous impacts on nature and people worldwide because of undeterred human behaviors.3 The World Meteorological Organization reports that the warmest years on record globally were recorded between 2015 and 2020 after a notable succession of upward trends of global mean temperature over previous decades.4 The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) attributes the disturbing warming trend to human-generated causes, which include carbon emissions.5 The implications of the global warming trend are vast and worrisome. Record-breaking heat, rain, flooding, droughts, wildfires, and hurricanes have been found to be more frequent, intense, and widespread.6 Between 2030 and 2050, climate change is expected to cause approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from malnutrition, diarrhea, malaria, and heat stress alone.1

Unfortunately, the pediatric population is vulnerable in unique ways to climate stressors. Children younger than 5 years potentially shoulder up to 88% of the global disease burden from climate change.7 Of further concern regarding the social determinants of health (SDOH), children from communities of color and lower socioeconomic status will disproportionately experience negative health sequelae and have fewer available resources to adapt to global warming.8

The science of climate change

Multiple peer-reviewed studies from research groups worldwide support the accuracy and consensus of powerful evidence that humans are changing the earth’s climate primarily through greenhouse gas emissions.9 The greenhouse effect is the process through which heat is trapped near the earth’s surface by substances known as greenhouse gases. Greenhouse gases consist of carbon dioxide, methane, ozone, nitrous oxide, chlorofluorocarbons, and water vapor, which help to maintain a comfortable temperature for life on Earth.9

However, human activities contribute to increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. These human activities include the use of various sources of greenhouse gas emissions, such as industrial factories, transportation (cars and planes), deforestation (cutting down trees), and agriculture (livestock).9 The enhanced greenhouse effect results in a global temperature rise, the decline of polar ice caps and shrinking glaciers leading to rising sea levels, and extreme weather events such as hurricanes, droughts, and heavy rainfall (Figure 1).5

The global effects of climate change are vast and multifaceted, impacting various aspects of the environment, economy, and human health. Environmentally, more frequent and severe heat waves are occurring due to the overall temperature rise of the globe. Decreased freshwater availability influences agriculture, industry, and drinking water supplies.11 Although some regions may face prolonged droughts, others may experience frequent rainfall, leading to flooding, with rising sea levels threatening coastal communities and ecosystems.12 Many animal species are endangered by changing climates, leading to shifts in habitats, migration patterns, and heightened extinction rates.12 Ocean acidification from elevated carbon dioxide levels impacts marine life and decreases coral reef growth.12

Economically, changes in weather patterns can impact agricultural productivity by harming crops, which reduces produce quality and increases the potential for contamination and the need for pesticide use, leading to food shortages and increased prices.6 Economic losses are also sustained with infrastructure damage from extreme weather events such as hurricanes, floods, and wildfires, leading to costly repairs.6 Additional financial burdens on health care systems related to heat waves, vector-borne diseases, and poor air quality also raise health costs.6

Social inequalities are exacerbated in vulnerable populations, such as in low-income communities and developing countries, who are disproportionately affected by climate change.12 Rising sea levels, extreme weather, and scarcity of resources may force people to migrate, with displacement leading to conflicts and pressure on other areas.12 Overall, environmental stress may lend itself to social unrest, political instability, and conflicts over scarce resources such as water and fertile land.12

The health effects of climate change on children

Ahdoot et al found that children are at much greater risk due to climate-related health injustices.13 Children’s unique behavior patterns; developing organ systems and physiology; increased exposure to air, food, and water in relation to body weight; and dependence on caregivers for resources were cited as major contributors to climate-related injustices. Physical displacement and migration disrupt education, social networks, and mental well-being.14 These disruptions have the potential for long-lasting effects on the pediatric population. Additionally, vulnerable populations and communities have limited access to resources and adaptive measures, adding to the negative effects of climate change and extreme weather.

The profound effect of environmental change can impact a developing fetus. Pregnant women who are exposed to extreme temperatures can experience stress and physiological changes that affect fetal development.15 Maternal stress, trauma, and anxiety may result in DNA methylation changes in the HSD11B2 gene in the placenta, which may result in neurodevelopmental conditions.14 There has been evidence suggesting that exposure to high temperatures during pregnancy is associated with a higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight.16 In-utero exposure to extreme temperatures and pollutants increases the risk of asthma, infectious diseases, and other health issues in children.15

Increased respiratory challenges in children are linked to extreme weather. Evidence from 2024 supports a link between extreme weather and increased asthma attacks in children.17 Extreme weather can impact air pollution and aeroallergens. The increased prevalence of asthma exacerbations is expected to increase in the future, having a substantial impact on quality of life.18 Increased wildfire smoke also contributes to respiratory problems in children, including asthma exacerbations. A 2024 study reported increased hospital admissions for pediatric respiratory issues during wildfire seasons.19

Children are particularly vulnerable to heat-related illnesses and dehydration related to extreme temperatures. Uibel et al found that a child’s response to heat due to their rapid growth and development, smaller body size, greater skin surface area relative to body mass, and decreased ability to regulate core body temperature contributes to morbidity associated with extreme heat.20 During periods of extreme heat, there has been a noticeable rise in cases of heatstroke, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances among the pediatric population. Extremes related to droughts and precipitation affect food security, which impacts nutrition. Van der Merwe et al determined that malnutrition rates in children are associated with a decline in food availability, as food systems are threatened by climate variables, including extreme weather events, seasonality and changes to ecosystems, biodiversity, and natural resources.21

Extreme heat can contribute to the spread of infectious diseases, as higher temperatures can enhance the reproduction rates of bacteria and viruses.22 Climate change also alters vector habitats, increasing the incidence of diseases. The EPA found increased incidence of Lyme disease and dengue fever among children,23 as well as a rise in pediatric vector-borne diseases in new geographic areas. Increased precipitation and flooding can lead to waterborne diseases such as cholera and other pathogens such as the norovirus or bacteria of the genus Vibrio, either through open wounds in the skin or ingesting drinking water. Depending on the species, pathogens can cause a range of health effects, including ear infections, flulike symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, or death (Figure 2).23

Rising temperatures due to climate change are expected to contribute to the number of children presenting with kidney stones, which are painful deposits of minerals and salts that form in concentrated urine and can get caught in the urinary tract. An increased incidence of kidney stone presentations has been noted following hot days. Researchers at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia found that even if measures are put in place to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, we can expect to see a rise in the incidence of kidney stones in children due to a progressive rise in temperatures due to climate change.24

Floods increase the risk of injuries among children, including drowning and blunt trauma,25 highlighting the urgent need for more resources devoted to pediatric disaster-preparedness efforts.

Pappas identified a variety of stresses having behavioral and mental health effects related to extreme heat.27 The stress associated with prolonged heat waves and the disruption they cause can have profound psychological effects on children. Increased rates of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues, such as posttraumatic stress disorder, have been reported. Heat can also have direct effects on mood and cognition, causing the perception of others’ behavior as aggressive, potentially contributing to violent behavior. Some psychotropic medications can affect an individual’s heat tolerance, making them more vulnerable to heat exhaustion or heatstroke. Therefore, a child with underlying psychological illness already being treated may pose an additional risk.

Climate change harm reduction: The role of pediatric nurses

Children are particularly affected by the hazardous effects of climate change because of their unique physical, cognitive, behavioral, and social considerations.6 The pediatric population is vulnerable to the negative aftermath of climate change that can potentially result in lifelong sequelae on learning, physical health, chronic disease, and other complications.6 According to the CDC, the health outcomes of these threats include increased respiratory and cardiovascular disease, unintentional injuries, premature deaths, heightened risks to infectious diseases, and graver mental health illnesses.28

Nurses are trusted experts in child health who can promote sustainable strategies and interventions that can prevent harm to children from climate change.7 Nurses can guide families on how to prepare for extreme weather events, educate on the management of chronic conditions such as asthma that are affected by reduced air quality, advise on the prevention of vector-borne illness, and promote services for mental health.7

Pediatric nurses can promote climate literacy for themselves and their patients and families by referring to veritable information such as the EPA’s America’s Children and the Environment website, which provides a variety of resources on national trends and data on the environment and children’s health.29 Nurses can role model global citizenship with thoughtful human behaviors and activities that mitigate climate change by adopting cleaner forms of energy, minimizing waste, and advocating for policies and environmental campaigns that protect natural resources and reduce impurities in drinking water, chemicals in food, and exposure to air pollution.7

Pediatric nurses can participate in professional organizations such as the Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments, which is a network of international nurses advocating for environmental health in workplaces and governmental institutions, implementing research that addresses environmental health concerns, and providing anticipatory guidance to pregnant women and parents about environmental risks to children.30 Pediatric nurses must also be aware of how climate change impacts other SDOH, such as food insecurity, to effectively address varied unmet social needs and promote climate justice.8

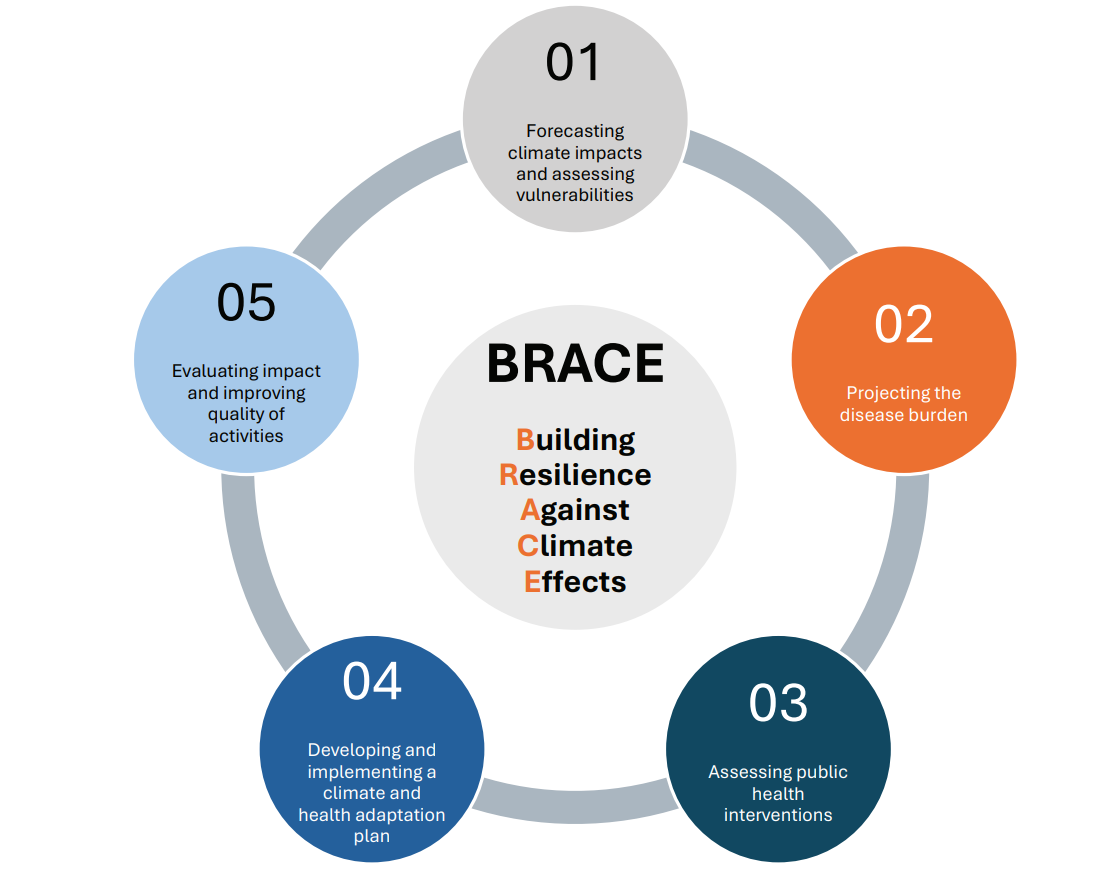

The CDC’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) is a 5-step framework that allows health officials to develop strategies and programs to help communities prepare data and projections with epidemiologic analysis to more effectively anticipate, prepare for, and respond to a range of climate-sensitive health impacts.31 The BRACE framework also blends justice, equality, diversity, and inclusion into their climate and health efforts (Figure 3).31

Conclusion

Climate change brings about a complex, difficult, and stressful time, particularly impacting the pediatric population. The complicated cluster of physical and psychosocial effects may have long-term implications. Nurses working with children can help minimize and avert consequences by optimizing health outcomes with screening, evidence-based interventions, and advocacy. The critical need for public health policies and sustainable interventions at the local, state, national, and international levels to mitigate climate change risks is essential to limit the consequences. Health care and policymaking initiatives also need to incorporate the SDOH perspective to ensure equity and justice for all. Suggested next steps include improvements to public infrastructure and access to essentials such as electricity, food, and health care. Recommendations for improved educational and social institutions with ongoing research can be effective deterrents against climate change threats, thereby improving population health.21 When advocating for the health of our planet, we are also ensuring the health of our children for today and in the future.

References:

1. Climate change. World Health Organization. October 12, 2023. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

2. Health and climate change. World Bank Group. November 16, 2024. Accessed November 19, 2024. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/brief/health-and-climate-change

3. What is climate change? United Nations. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

4. Rate and impact of climate change surges dramatically in 2011-2020. Press release. World Meteorological Organization; December 5, 2023. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://wmo.int/news/media-centre/rate-and-impact-of-climate-change-surges-dramatically-2011-2020

5. Climate change science. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/climatechange-science

6. Impacts of climate change. US Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/climatechange-science/impacts-climate-change

7. Climate change: the impact on children’s health. American Academy of Pediatrics. Updated January 10, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/environmental-health/promoting-healthy-environments-for-children/climate-change/

8. Ragavan MI, Marcil LE, Garg A. Climate change as a social determinant of health. Pediatrics. 2020;145(5):e20193169. doi:10.1542/peds.2019-3169

9. Evidence. NASA. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/evidence/

10. Scientific consensus. NASA. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://science.nasa.gov/climate-change/scientific-consensus/

11. Climate change impacts on freshwater resources. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-impacts-freshwater-resources

12. Climate change impacts. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.noaa.gov/education/resource-collections/climate/climate-change-impacts

13. Ahdoot S, Baum CR, Cataletto MB, et al. Climate change and children’s health: building a healthy future for every child. Pediatrics. 2024;153(3):e2023065505. doi:10.1542/peds.2023-065505

14. Subramanyam AA, Somaiya M, De Sousa A. Mental health and well-being in children and adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2024;66(suppl 2):S304-S319. doi:10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_624_23

15. Chersich M, Lakhoo DP. Heat exposure during pregnancy can lead to a lifetime of health problems. PreventionWeb. June 19, 2024. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://www.preventionweb.net/news/heat-exposure-during-pregnancy-can-lead-lifetime-health-problems

16. Ha S. The changing climate and pregnancy health. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2022;9(2):263-275. doi:10.1007/s40572-022-00345-9

17. Rida J, Bouchriti Y, Ait Haddou M, Achbani A, Sine H, Serhane H. Meteorological factors and climate change impact on asthma: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. J Asthma. 2024;61(12):1601-1610. doi:10.1080/02770903.2024.2375272

18. Bentué-Martínez C, Rodrigues M, Llorente González JM, Sebastián Ariño A, Zuil Martínez M, Zúñiga-Antón M. Spatial patterns in the association between the prevalence of asthma and determinants of health. Geogr Anal. 2024;56(2):265-283. doi:10.1111/gean.12380

19. Extreme heat associated with children’s asthma hospital visits. ScienceDaily. May 20, 2024. Accessed August 6, 2024. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2024/05/240520122830.htm

20. Uibel D, Sharma R, Piontkowski D, Sheffield PE, Clougherty JE. Association of ambient extreme heat with pediatric morbidity: a scoping review. Int J Biometeorol. 2022;66(8):1683-1698. doi:10.1007/s00484-022-02310-5

21. van der Merwe E, Clance M, Yitbarek E. Climate change and child malnutrition: a Nigerian perspective. Food Policy. 2022;113:102281. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2022.102281

22. Lian X, Huang J, Li H, et al. Heat waves accelerate the spread of infectious diseases. Environ Res. 2023;231(Pt 2):116090. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.116090

23. Climate change and children’s health and well-being in the United States. Environmental Protection Agency. April 2023. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2023-04/CLiME_Final%20Report.pdf

24. Kaufman J, Vicedo-Cabrera AM, Tam V, Song L, Coffel E, Tasian G. The impact of heat on kidney stone presentations in South Carolina under two climate change scenarios. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):369. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04251-2

25. Fanny SA, Kaziny BD, Cruz AT, et al. Pediatric emergency departments and urgent care visits in Houston after Hurricane Harvey. West J Emerg Med. 2021;22(3):763-768. doi:10.5811/westjem.2021.2.49050

26. Climate change and children’s health. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/climateimpacts/climate-change-and-childrens-health

27. Pappas S. Extreme heat and poor air quality are threatening childrens’ mental health. How can psychologists help? American Psychological Association. September 19, 2023. Updated October 12, 2023. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.apa.org/topics/climate-change/extreme-heat-warming-climate

28. Effects of climate change on health. CDC. February 29, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/climate-health/php/effects/index.html

29. America’s children and the environment. Environmental Protection Agency. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.epa.gov/americaschildrenenvironment

30. Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments. Accessed October 30, 2024.

https://envirn.org/

31. About Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) framework. CDC. April 17, 2024. Accessed October 30, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/climate-health/php/brace/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/BRACE.htm

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.

Overview of biologic drugs in children and adolescents

March 10th 2025A presentation at the 46th National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (NAPNAP) conference explored the role of biologics in pediatric care, their applications in various conditions, and safety considerations for clinicians.