Dehydrated infant with fast breathing and sunken anterior fontanel

A 9-month-old girl with a history of grunting and poor weight gain for a few months is evaluated in the emergency department for dehydration and respiratory distress. What’s the diagnosis?

THE CASE

A 9-month-old girl presents to the emergency department (ED) from her primary care provider’s office for further evaluation of grunting and poor weight gain. She was seen in the office on the day of presentation for her well-child check when the nurse practitioner noticed that she was grunting, tachypneic, and appeared dehydrated with a sunken anterior fontanel.

Additional history reveals sweating and fatigue with feeds beginning around aged 2 months. Patient can breastfeed for maximum 5 to 10 minutes on 1 breast before fatiguing. She also eats some puréed food and baby snacks. Parents deny any episodes of cyanosis, with no blue discoloration ever noted centrally or peripherally. At aged 6 months, patient’s weight plateaued and she was referred to gastroenterology but has not been seen at time of presentation. She is otherwise described as developmentally appropriate and is up to date on her immunizations.

Examination and imaging studies

On physical exam her vitals are as follows: temperature, 98.6 °F (37.0 °C); heart rate, 130 beats/min; respiratory rate, 51 breaths/min; and blood pressure 91/67 mm Hg. Her weight is below the 1st percentile for her age (6.38 kg, 0.92%), as is her weight for length (6.38 kg/71.1 cm, 0.07%). Her respiratory exam is notable for tachypnea, occasional grunting, and both subcostal and supraclavicular retractions. Cardiac exam reveals tachycardia, S1/S2 with appreciable gallop, and a grade 3/6 systolic murmur heard throughout the precordium but loudest at the left sternal border. Peripheral pulses are slightly diminished. She has hepatomegaly with liver edge palpable 3 cm below right costal margin. Remainder of exam is unremarkable. Initial workup includes normal complete blood count and basic metabolic panel. Chest x-ray (CXR) obtained showing impressive cardiomegaly and bilateral vascular congestion. B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) elevated to 2,709 pg/ml with a normal troponin-I of 0.023 ng/ml. Further testing ultimately revealed the diagnosis.

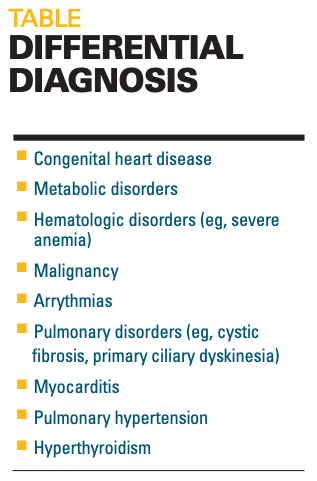

Differential diagnosis

For this patient’s respiratory symptoms and failure to gain weight appropriately, differential diagnosis includes cardiac (congenital heart defect, arrythmia, myocarditis, pulmonary hypertension), inborn error of metabolism, hyperthyroidism, hematologic (such as severe anemia), neoplasm, and pulmonary (such as cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia). Her lack of growth is suggestive of an underlying disease process. When coupled with her exam findings consistent with heart failure, the diagnosis of congenital heart disease becomes the most likely. Inborn error of metabolism is possible but less likely given normal basic metabolic panel. Myocarditis secondary to illness as cause of heart failure should be considered.

ACTUAL DIAGNOSIS

Because of the patient’s concerning CXR and elevated BNP, pediatric cardiology is consulted for suspected cardiac anomaly. An echocardiogram demonstrates a massively dilated left atrium and left ventricle with severe mitral regurgitation. The pulmonary artery is markedly dilated as well. The right coronary artery is dilated and visualized but the left coronary artery cannot be seen. As a result of these findings, the patient is transferred to a local children’s hospital with a cardiac intensive care unit. She is given a dose of furosemide prior to transfer given her degree of volume overload.

THE CONDITION

Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery, or ALCAPA, is a rare condition and the prevalence has not been well described.1 Coronary artery anomalies have been estimated to occur in 0.2 to 1.2% of the general population based on imaging studies, however the majority have little clinical significance.2 In normal anatomic development, both the right and left coronary arteries originate from the aorta. However, in ALCAPA, the left coronary artery arises from the main pulmonary artery (or less commonly, from the right pulmonary artery) and then runs along the aorta before following the usual left coronary distribution. The blood flow in the coronary artery is dependent on the diastolic pressure which places ALCAPA patients at risk of left ventricular dysfunction and ischemia whenever the diastolic pressure in the pulmonary artery decreases.

Symptoms presenting in infancy typically include crying or sweating during feeds, rapid breathing, poor feeding, and signs of pain or distress that are often confused with colic. In instances of symptom development, there are no collaterals arising from the right coronary artery. As pulmonary vascular resistance decreases, coronary steal occurs from the myocardium and blood flows instead into the pulmonary artery. There is limited blood supply to the left ventricle and because of decreased myocardial perfusion, patients develop mitral insufficiency and congestive heart failure or dilated cardiomyopathy. In children older than 2 years, there is substantial collateral vessel formation and patients will often be asymptomatic with findings of a murmur on exam or cardiomegaly on chest radiography. However, even in the absence of symptoms, there is ischemic injury and eventually development of progressive left ventricular dilatation.3

Management

The mainstay of therapy for ALCAPA presenting as congestive heart failure is surgical correction to return a 2–coronary-artery circulation. This often consists of reimplantation surgery in which the coronary artery is detached from the pulmonary artery and then sutured to the aorta in the correct location. Following surgery, most patients do well with a good quality of life. Medications, such as diuretics, are often needed initially but weaned off over weeks to months following surgery. Without surgical correction, the mortality rate is estimated to be close to 90% within the first year of life for those with infantile ALCAPA.4

PATIENT COURSE

The patient underwent surgical correction on hospital day 2. Following discharge from the hospital, she was followed by pediatric cardiology weekly and then spaced to 2-month interval visits. Parents report that patient is now 5 months post-op and doing very well. Her sweating has improved and she no longer has evidence of respiratory distress. She lost weight in the initial postoperative period but since then has slowly been gaining weight with fortified formula. She is active and playful and recently celebrated her first birthday.

DISCUSSION

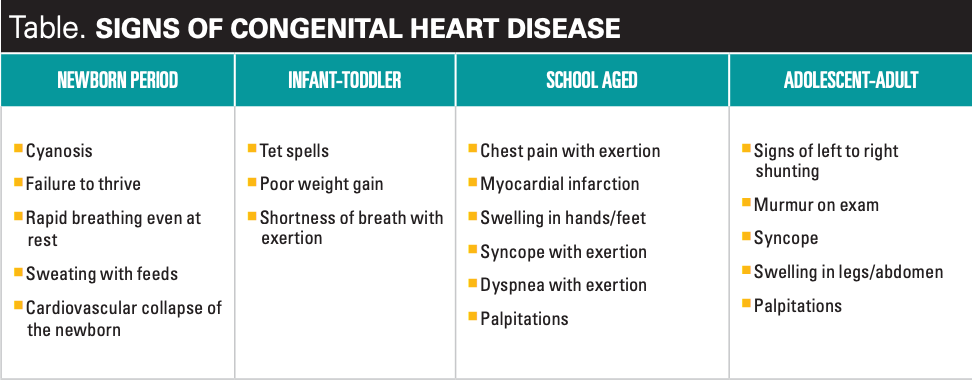

Congenital heart disease impacts approximately 8 in 1000 live births with about one-third of these babies requiring intervention by catheterization or surgery within the first year of life. The critical congenital heart disease (CCHD) screen performed prior to discharge from the hospital of newborns in all 50 states has resulted in a 33% decrease in early infant death from critical congenital heart disease.5 However, the sensitivity of CCHD screening is estimated to be only 50% to 76% and there are multiple conditions that are not picked up by this screening.6,7 The pediatric health care provider must carefully watch for the develop of symptoms in their patients that would indicate the presence of congenital heart disease (Table).

In the case presented, the parents reported that the patient was sweaty and tired with feeds since aged 2 months, if not before. They describe that she would “snack” and could not feed for longer than 5 to 10 minutes at a time without getting tired and sweating profusely. Once the patient began crawling and became more active, parents reported profuse diaphoresis which they attributed to the warm climate and summer heat. It is important for the pediatrician to screen for these symptoms during routine well-child checks to ensure that patients with congenital heart disease who are not identified by routine newborn screening are later identified.

To read more from the May, 2023, issue of Contemporary Pediatrics®, click here.

References:

1. Jinmei Z, Yunfei L, Yue W, Yongjun Q. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery (ALCAPA) diagnosed in children and adolescents. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15(1):90. doi:10.1186/s13019-020-01116-z

2. Angelini P. Novel imaging of coronary artery anomalies to assess their prevalence, the causes of clinical symptoms, and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7(4):747-754. doi:10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000278

3. Hauser M. Congenital anomalies of the coronary arteries. Heart. 2005;91(9):1240-1245. doi:10.1136/hrt.2004.057299

4. Dodge-Khatami A, Mavroudis C, Backer C. Anomalous origin of the left coronary artery from the pulmonary artery: collective review of surgical therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(3):946-955. doi:10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03633-0

5. Abouk R, Grosse SD, Ailes EC, Oster ME. Association of US state implementation of newborn screening policies for critical congenital heart disease with early infant cardiac deaths. JAMA. 2017;318(21): 2111-2118. doi:10.1001/jama/2017.17627

6. Ailes EC, Gilboa SM, Honein MA, Oster ME. Estimated number of infants detected and missed by critical congenital heart defect screening. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1000-1008. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3662

7. Fisher JD, Bechtel RJ, et al. Clinical spectrum of previously undiagnosed pediatric cardiac disease. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(5): 933-936.doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.029

Newsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.