Dyslexia: What you need to know

By being vigilant to signs of dyslexia, dispelling the myths, and helping to coordinate care, pediatricians can help children with dyslexia enjoy success in school and in daily life.

Table 1

Table 2

Table 3

Learning to read is an extremely complex process, which has been described to be as challenging as learning rocket science.1 Therefore, it is not too surprising that, for many reasons, over 60% of children in America fail to meet standards for reading proficiency.2

Multiple issues may underlie this reading difficulty, including poor early language development, inadequate instruction, insufficient reading practice, lack of background knowledge, and intellectual disability. In some children, however, the problem is the specific learning disability called dyslexia.

Dyslexia is by far the most common learning disability and is present in some degree in up to 20% of children.3 Just as early detection and intervention are crucial in medical diseases, the same is true in learning disabilities. The consequences of untreated dyslexia are broad and can be significant, including effects on academic success and psychosocial well-being. Children with dyslexia experience intense frustration; may act aggressively or withdraw; frequently become targets of bullying and ridicule; have low self-esteem; and may even develop mental health problems, including anxiety and depression.

Pediatricians have the opportunity and responsibility to enable detection and proper treatment of dyslexia in children. This article aims to provide information and strategies that will allow clinicians to best assist and advise patients and their parents.

Dyslexia defined

Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability characterized by difficulties with decoding (sounding out) words, fluent word recognition, and/or reading-comprehension skills. Children with dyslexia often develop secondary problems with comprehension, spelling, writing, and knowledge acquisition.

The difficulties found in dyslexia are usually caused by a phonological deficit (an auditory processing problem involving hearing the sounds in speech). The phonological deficit leads to difficulty connecting speech sounds to letters, which is a skill needed to decode the written word. Alternatively, dyslexia in some children results from problems with oral language skills, sight word recognition, processing speed, comprehension, attention, or verbal working memory.

Anatomical and imaging studies investigating brain development and function show a corresponding physical basis for dyslexia in language-related areas of the brain. The brains of persons with dyslexia function differently than the brains of “typical readers” before they even start to read, as dyslexics use an alternative pathway for reading. Specifically, these investigations reveal that persons with dyslexia have dysfunction in the left-hemisphere posterior reading areas with corresponding compensatory use of the bilateral inferior frontal gyri of both hemispheres and the right occipitotemporal area.3

In discussing the definition of dyslexia and its causes, it is also useful for pediatricians to be aware of the many myths and misperceptions that exist. Dyslexia is not a condition where readers see letters or words upside down or backwards. It is not related to visual or eye-tracking problems.4 In addition, dyslexia is not a developmental issue that children may be expected to outgrow; rather, it is a persistent lifelong condition.

Dyslexia also is not related to intelligence or laziness in a child. Dyslexia occurs in persons with low, normal, and high intelligence quotients (IQs) alike. The fact that dyslexia is not related to IQ, however, creates the potential for a significant learning disability to be overlooked in an otherwise bright child. Dyslexics are often perceived to be “lazy” or “not working up to their potential” when, in fact, they often work harder and longer than their peers.

In addition, there is no male predominance for dyslexia. It is found almost equally in boys and girls, but tends to be identified earlier and more often in boys, perhaps because boys tend to “act out” when they are unable to do a difficult task versus girls who are inclined to make themselves “invisible” in the classroom.

Detection and diagnosis

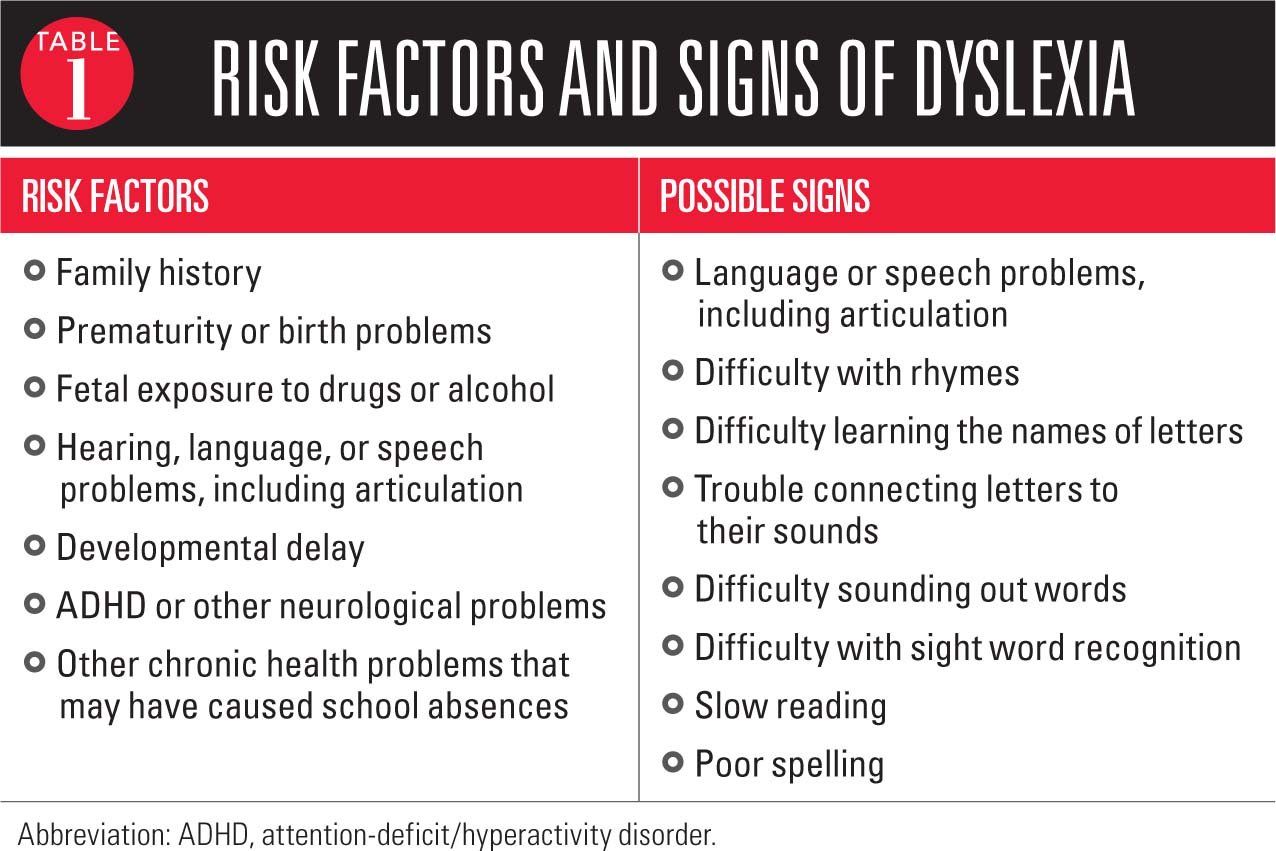

A diagnosis of dyslexia is established clinically based on history, observation, and a battery of age-appropriate educational tests interpreted by a knowledgeable, qualified professional. Although it is not up to pediatricians to make the diagnosis, an understanding of dyslexia can help to identify children by being attentive to risk factors and signs that are elicited in the medical and social history during well-child exams (Table 1).

Dyslexia is heritable and familial, and so the history should ascertain whether there is a family history of speech and language problems or dyslexia. Other risk factors for dyslexia include prematurity, neurological problems, and developmental or language delays.

Early warning signs for dyslexia in preschool-aged children include trouble learning nursery rhymes or playing rhyming games; confusing words that sound alike; mispronouncing words; and trouble recognizing letters of the alphabet.5 Early elementary school children with dyslexia often have difficulty learning the names and sounds of the letters; separating and blending sounds; sounding out words; recognizing sight words; and spelling. They often read slowly and dislike reading. A parent’s complaint that a child is not doing well in school should prompt questions to explore the presence of reading difficulties.

Although many dyslexic students are identified in the primary grades, dyslexia’s possible presence should not be overlooked in older children and teenagers. Signs in adolescents include a history of phonologically based reading difficulties, slow reading, choppiness when reading aloud, poor comprehension, and requiring more time to finish assignments or tests.5 These adolescent students also may have multiple school truancies and/or behavioral issues, such as anger, aggression, depression, or even suicidal tendencies and possibly alcohol or drug use.

If a family history of dyslexia or other risk factors exist, the child's early language development and school progress should be carefully monitored. A formal psychoeducational school evaluation is needed to identify dyslexia and will provide an understanding of the child’s strengths and weaknesses, the severity of the problem, and whether the child has a “specific learning disability” that is eligible for special education and support programs. Severe dyslexia typically qualifies a child for an Individualized Educational Plan, special education, and related services. The psychoeducational or broader neuropsychological or developmental-behavioral pediatric evaluation will identify comorbid conditions, and the findings will provide the foundation for a treatment plan.

Fortunately, individuals who have severe dyslexia are in the minority. The other side of the coin, however, is that those students whose disorder is more moderate or mild may not be readily recognized and/or may not qualify for treatment, although they would benefit from those services.

Treating dyslexia

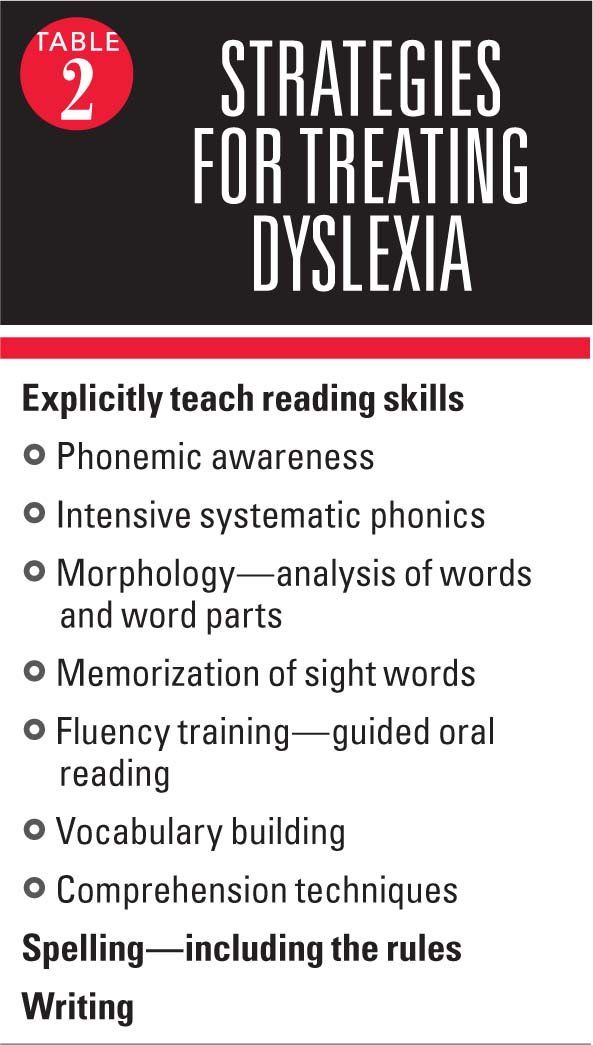

The prognosis for a child with dyslexia depends not only on the specific features of the disorder and its severity, but also on the timeliness and appropriateness of intervention (Table 2). Studies show that beginning remediation in first grade versus waiting 2 more years greatly increases the chance that a child will later be able to read at grade level.6 Nevertheless, it is never too late to help.

Effective intervention for dyslexia targets its etiology as a language-based disorder and should be provided by a professional with the appropriate training. Children with dyslexia are best served with lessons provided in small group settings, which bring together students who are at the same reading level, and include no more than 5 students. Remediation programs that follow the International Dyslexia Association guidelines call for a “Structured Literacy Approach.”

These programs explain language in an explicit, systematic, sequential, and multisensory manner. They include training in the 5 reading skills: 1) phonemic awareness (hearing the sounds in words); 2) phonics (correlating sounds with letters); 3) fluency (ability to read with speed, accuracy and expression); 4) vocabulary; and 5) comprehension. Emphasis is also placed on learning word structure, letter patterns, spelling, and writing.

Whereas early management of dyslexia focuses on remediation of the reading problem, for older students there is a shift toward providing tools and accommodations. Accommodations allow the student to access his/her higher-level thinking and reasoning skills. These measures include access to assistive technology (eg, recorded books, text reading software, note takers, spell checkers) as well as provisions to enable test taking (eg, extended testing time, a special quiet room, or preferential seating).

Pediatrician’s role

Parents of children with dyslexia often seek counsel from their pediatrician about dyslexia treatments, so clinicians should be aware of both the proven and unproven interventions being recommended and heavily promoted. By being informed about the variety of approaches, as well as being able to discuss the lack of evidence supporting the efficacy for the unproven interventions, pediatricians will be equipped to educate patients and their families, encourage positive proven approaches, discourage the use of unproven techniques, and thus prevent families from wasting valuable time and resources pursuing expensive, nonproductive therapies.

Non–evidence-based approaches promoted for remediation of reading difficulties in children with dyslexia include medication for vestibular dysfunction, chiropractic manipulation, physical exercises, and dietary supplementation or restrictions.5 In particular, however, the erroneous concept that dyslexia is a vision-based disorder has spawned a variety of interventions involving the use of training glasses, eye exercises, behavioral/perceptual vision therapy, and colored lenses and overlays. Although visual problems, including convergence insufficiency, can hamper reading, they are not the cause of dyslexia. Vision problems are not more common in children with reading impairment.4 Not only are vision-related approaches misdirected in theory, but authors of systematic literature reviews have concluded there is no scientific evidence of their efficacy for learning disabilities.3,7-9

Eye and vision problems occur in approximately 5% to 10% of early elementary students and 25% of high school students, and pediatricians should recognize that some treatable vision problems can masquerade as a learning problem or may be coexisting. For example, children with large amounts of farsightedness or astigmatism may be uninterested in books whereas children with nearsightedness may have difficulty seeing the board. Symptomatic convergence insufficiency, which occurs more rarely in elementary school-aged children, makes reading at near blurry and uncomfortable. Consequently, affected children may read only for short periods of time, and on that basis may be thought to have dyslexia or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), especially the inattentive type.

Pediatric ophthalmologists play a valuable role in the assessment of children with suspected or established learning disabilities, including dyslexia, to determine whether there are any eye or vision problems that could be interfering with learning or reading. As part of the management team for children with dyslexia, pediatric ophthalmologists can help families by reinforcing information on the condition, dispelling the myths, and providing guidance to resources available online, in print, and in the community.

Referral for an ophthalmologic evaluation is indicated when a vision problem is suspected or the child fails vision screening. The pediatric ophthalmologist will perform a complete dilated eye and vision examination, thoroughly evaluate near vision, and perform a cycloplegic refraction. Most ocular conditions found in children, including strabismus, amblyopia, convergence or focusing deficiencies, and refractive errors, are treatable with glasses and will improve quickly. Children diagnosed with symptomatic convergence insufficiency are usually prescribed convergence eye exercises to be performed at home. These exercises usually result in improved reading comfort within a few weeks. In-office exercises with at-home reinforcement are considered if a child continues to show signs and symptoms of convergence insufficiency.

It is crucial to understand that although these exercises may relieve eye strain, they are not a treatment for coexisting dyslexia. Furthermore, pediatricians should know that convergence insufficiency is frequently overdiagnosed. Any child who has been diagnosed with convergence insufficiency should be referred to a pediatric ophthalmologist for a second opinion as should any child who has been recommended vision therapy or tinted lenses or filters as treatment for a reading disability.

Caring for other conditions

The pediatric evaluation of a child presenting with reading difficulties or dyslexia should also include assessments for other potentially contributing, masquerading, or coexisting conditions. In addition to vision screening, these investigations should include hearing screening and evaluations for behavioral, medical, and mental health disorders. Notably, ADHD and reading disability are highly comorbid. The inattentive type of ADHD has been found in 18% to 42% of children with dyslexia, and rates of dyslexia among children with ADHD have been reported to be within a similar range.10 Dyslexia also may be associated with oppositional defiant disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, anxiety, and depression.

Counselling and advocacy

Some pediatricians can help to advocate for the child as needed, for example, by writing a letter to request an evaluation or accommodations. To ensure that children get appropriate care, pediatricians should be prepared to provide families with names of professionals in their area who are qualified to evaluate and treat children with dyslexia. Children who have not been making progress after a prior psychoeducational evaluation and interventions could benefit from referral for further evaluation by a developmental-behavioral pediatrician or neuropsychologist. Although private evaluation of a child with suspected dyslexia may be expensive, a proper diagnosis may save many years of frustration and failed education, as well as thousands of dollars on unnecessary and unsupported treatments.

Pediatricians should be sympathetic to the stress that a child with dyslexia and his or her family is experiencing and should provide encouragement and emotional support. In addition, while counselling parents to support their child’s efforts at reading, pediatricians should also advise them to pursue their child’s strengths and allow time for activities in which the child finds enjoyment and excels.

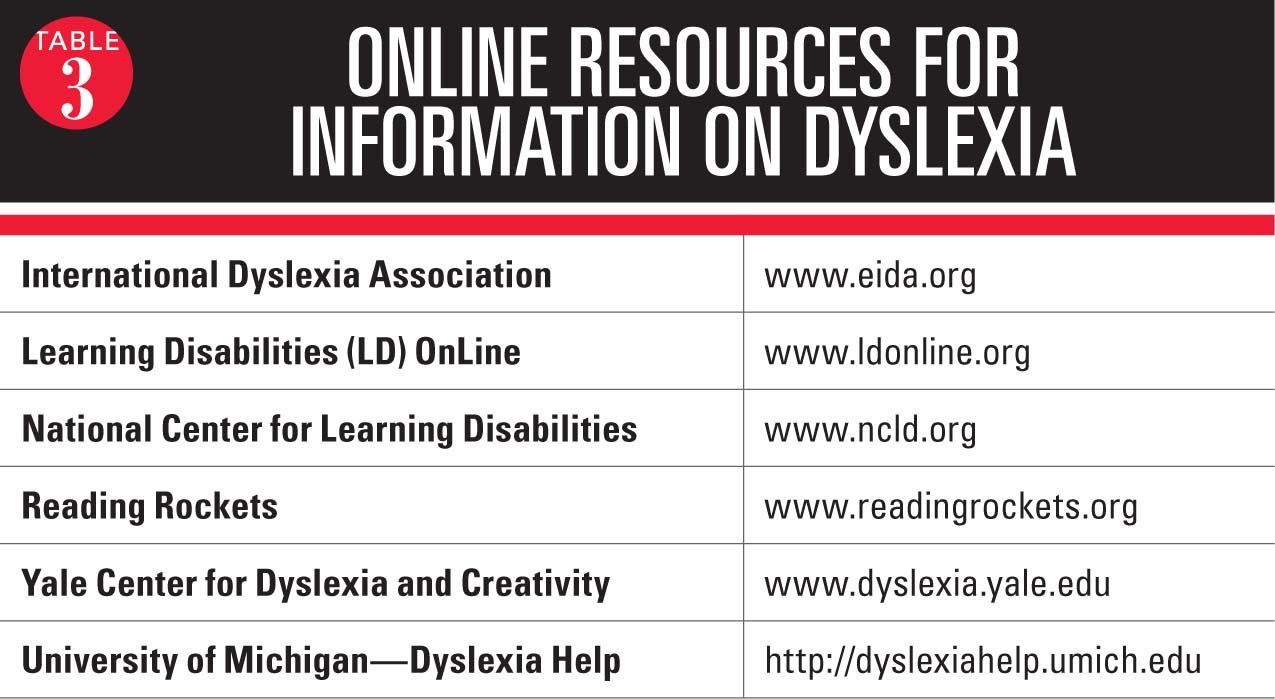

Pediatricians also should have available educational materials and/or lists of resources where families can get information about dyslexia, its evaluation and treatment, and their child’s rights for evaluation, special services, and accommodations as defined by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and Section 504 of the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). Table 3 lists several useful websites for more information.

Finally, the role of the pediatrician in helping children to become proficient readers begins early in the provider-family relationship, long before considering whether children are at risk for or showing signs of dyslexia. Recognizing that oral language is the foundation for reading and that children with speech and language delay or difficulties have a 50% likelihood of having difficulties learning to read, pediatricians can have an important impact by promoting early language development. The Books Build Connections Toolkit, developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and Reach Out and Read, contains material for pediatricians and parents and offers a practical resource to assist in these efforts.11

Conclusion

Dyslexia is a common and lifelong language-based learning disability that may be detected as early as kindergarten or first grade. Affected children are most likely to obtain the greatest benefit when the problem is identified early followed by prompt initiation of appropriate language and reading instruction. Care should be taken to avoid using ineffective methods of treatment that waste time and family resources and often critically delay proper remediation.

By being vigilant to signs of dyslexia, dispelling the myths surrounding this condition, helping to coordinate care, and providing support and encouragement, pediatricians with the aid of pediatric ophthalmologists can help children with dyslexia enjoy success in school and in their daily life.

References:

1. Moats LC. Teaching reading is rocket science: What expert teachers of reading should know and be able to do. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers; 1999. Available at:

http://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/reading_rocketscience_2004.pdf. Accessed July 19, 2016.

2. Nation’s Report Card. Nine subjects, three grades, one report card. Available at: http://www.nationsreportcard.gov/. Accessed July 19, 2016.

3. Handler SM, Fierson WM, Section on Ophthalmology; Council on Children with Disabilities; American Academy of Ophthalmology; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Association of Certified Orthoptists. Learning disabilities, dyslexia, and vision. Joint Technical Report. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3):e818-e856.

4. Creavin AL, Lingam R, Steer C, Williams C. Ophthalmic abnormalities and reading impairment. Pediatrics. 2015;135(6):1057-1065.

5. Shaywitz SE, Gruen JR, Shaywitz BA. Management of dyslexia, its rationale, and underlying neurobiology. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54(3):609-623.

6. Torgesen JK. Avoiding the devastating downward spiral: the evidence that early intervention prevents reading failure. Available at: http://www.aft.org/periodical/american-educator/fall-2004/avoiding-devastating-downward-spiral. Accessed July 19, 2016.

7. Fletcher JM, Francis DJ, Morris RD, Lyon GR. Evidence-based assessment of learning disabilities in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(3):506-522.

8. Barrett BT. A critical evaluation of the evidence supporting the practice of behavioural vision therapy. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2009;29(1):4-25.

9. Ritchie SJ, Della Sala S, McIntosh RD. Irlen colored overlays do not alleviate reading difficulties. Pediatrics. 2011;128(4):e932-e938.

10. Germanò E, Gagliano A, Curatolo P. Comorbidity of ADHD and dyslexia. Dev Neuropsychol. 2010;35(5):475-493.

11. American Academy of Pediatrics. Books Build Connections Toolkit. Available at: https://littoolkit.aap.org/Pages/home.aspx. Accessed July 19, 2016.