Fever and Neck Swelling in a Toddler With Growth Delay

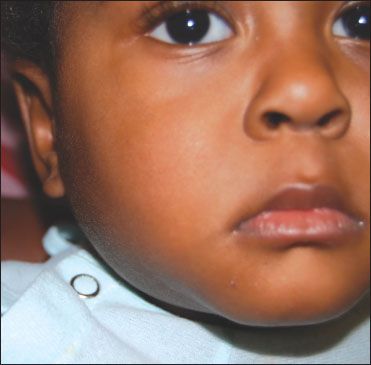

A 20-month-old boy brought to the emergency department with swelling on the right side of the neck and fever (temperature, 39.3°C [102.7°F]) of 1 day’s duration. The parents reported that the child had had intermittent fevers and poor weight gain for the past 3 months but no vomiting, diarrhea, rash, drooling, or difficulty in swallowing.

HISTORY

A 20-month-old boy brought to the emergency department with swelling on the right side of the neck and fever (temperature, 39.3°C [102.7°F]) of 1 day's duration. The parents reported that the child had had intermittent fevers and poor weight gain for the past 3 months but no vomiting, diarrhea, rash, drooling, or difficulty in swallowing.

Patient had had pneumonia 3 times since birth. Two maternal cousins had chronic granulomatous disease. No family history of travel outside the United States.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Temperature at the time of admission, 37°C (98.6°F); heart rate, 132 beats per minute; respiration rate, 43 breaths per minute; oxygen saturation, 100% while breathing room air; and blood pressure, 95/51 mm Hg. Weight, 9.4 kg; height, 76.5 cm; and head circumference, 46 cm (all growth parameters less than the 5th percentile).

Soft, 3 × 2-cm mass on the right side of the neck, mildly tender on palpation. Large anterior cervical lymph nodes on the right side. Lungs, clear to auscultation. Heart rate and rhythm, regular without murmurs. Abdomen soft, nondistended, without hepatosplenomegaly.

LABORATORY AND RADIOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

White blood cell count, 16,700/μL; hemoglobin level, 8.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 27.5%; platelet count, 409,000/μL. CT scan of the neck revealed a large mass (possibly a collection of infected lymph nodes), bilateral cervical adenopathy, and possible fluid in the retropharyngeal space.

INITIAL TREATMENT

Intravenous clindamycin started for coverage for gram-positive and anaerobic organisms. Child became febrile over the next 48 hours. Incision and drainage of the mass was performed. Culture of the lymph nodes grew Serratia marcescens.

WHAT'S YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Answer on Next Page

ANSWER: CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS DISEASE

Children with chronic granulomatous disease cannot generate microbicidal superoxide and reactive oxygen species (hydrogen peroxide, hydroxyl anion and hypochlorous acid) from oxygen in their phagocytes because of an inherited defect of the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase system. This leads to a reduced ability to fight off infections produced by catalase-positive organisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus,Escherichia coli, and S marcescens. Microorganisms are phagocytosed normally but persist within phagocytic cells. The resulting foci stimulate granuloma formation. Affected children present with recurring infections, such as pneumonia, pyoderma, abscesses, suppurative adenitis, osteomyelitis, bacteremia, and fungemia.1

The incidence is 1 in 200,000; the mean age at diagnosis is 3 years for children with the X-linked forms (70% of cases) and 7 years for children with the autosomal recessive forms.2

DIAGNOSIS

Chronic granulomatous disease can be diagnosed with a nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) test. This determines the percentage of phagocyte NADPH oxidase activity. Another option is the dihydrorhodamine 123 flow cytometry test, which is a quantitative determination of phagocyte reactive oxygen production. In utero diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease is also possible.3

A definitive diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease can be made when the patient has an abnormal NBT test/dihydrorhodamine 123 flow cytometry test result and 1 of the following criteria:

A probable diagnosis can be made when the patient has an abnormal NBT test result and 1 of the following criteria:

MANAGEMENT

The basis of the management of chronic granulomatous disease includes early diagnosis and treatment of infections, prophylactic antibiotics, and interferon-γ.

Acute infections must be diagnosed and treated promptly with parenteral antibiotics and usually require several weeks of treatment. Antibiotics chosen should cover a broad spectrum of gram-negative bacteria, S aureus, and Nocardia species. Intravenous antibiotic therapy must be followed by prolonged oral therapy, sometimes for months. Fungal infections should be treated with appropriate antifungal therapy. In addition, surgical procedures, such as drainage of abscesses and excision of consolidated suppurative and granulomatous lesions, may be required.

Affected patients should receive all routine immunizations as well as yearly influenza vaccine; however, BCG vaccine should be avoided. Daily prophylaxis with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is required, because it has been shown to decrease the incidence of bacterial infections without increasing the incidence of fungal infections. Trimethoprim or cephalosporins may be used in patients with sulfa allergies.5 Interferon-γ is also recommended. Although its mechanism of action is not fully understood, it may involve an increase in oxidantindependent antimicrobial pathways.6

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can restore normal neutrophil function and can be curative.7 T-cell depletion of the graft has resulted in a decreased incidence of graft versus host disease. The best response in studies was obtained when patients were pretreated with parenteral antibiotics and antifungals before transplantation. However, because of the high mortality associated with this procedure, it is reserved for patients in whom all other therapies fail.8

Ongoing trials of gene therapy seem promising since the exact genetic defect has been determined.

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis has improved dramatically with current treatment. The median survival is 20 to 25 years, and the mortality rate is 2% to 3% per year. Patients with the X-linked form usually have more severe disease than those with autosomal recessive disease.4

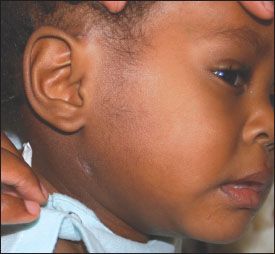

Figure – Decreased swelling of the neck mass was noted in the child 14 days after the initiation of antibiotic treatment. Results of a dihydrorhodamine 123 flow cytometry assay were consistent with chronic granulomatous disease.

OUTCOME OF THIS CASE

Results of a dihydrorhodamine 123 flow cytometry assay were consistent with the X-linked form of chronic granulomatous disease. Clindamycin was discontinued and intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam and oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole were started. The neck mass gradually decreased in size (Figure). When the patient defervesced, a percutaneous catheter was placed for completion of a 2-week course of intravenous antibiotic therapy at home.

The child is currently being monitored by infectious disease and immunology specialists. He will undergo evaluation for eventual hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Boxer LA. Disorders of phagocyte function. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, eds.

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics

. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:chap 129.

2.

Winkelstein JA, Marino MC, Johnston RB Jr, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease. Report on a national registry of 368 patients.

Medicine (Baltimore)

. 2000;79:155-169.

3.

Chien SC, Lee CN, Hung CC, et al. Rapid prenatal diagnosis of X-linked chronic granulomatous disease using a denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography (DHPLC) system.

Prenat Diagn

. 2003;23:1092-1096.

4.

Conley ME, Notarangelo LD, Etzioni A. Diagnostic criteria for primary immunodeficiencies. Representing PAGID (Pan-American Group for Immunodeficiency) and ESID (European Society for Immunodeficiencies).

Clin Immunol

. 1999;93:190-197.

5.

Liese J, Kloos S, Jendrossek V, et al. Long-term follow-up and outcome of 39 patients with chronic granulomatous disease.

J Pediatr

. 2000;137:687-693.

6.

Marciano BE, Wesley R, De Carlo ES, et al. Long-term interferon-gamma therapy for patients with chronic granulomatous disease.

Clin Infect Dis

. 2004;39:692-699.

7.

Seger RA. Modern management of chronic granulomatous disease.

Br J Haematol

. 2008;140:255-266.

8.

Güngör T, Halter J, Klink A, et al. Successful low toxicity hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for high-risk adult chronic granulomatous disease patients.

Transplantation

. 2005;79:1596-1606.

Newsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.