Groundbreaking guidelines issued for unexplained pediatric death

New consensus guidelines clarify the procedural guidance for investigation, certification, and reporting of sudden unexplained pediatric deaths to help medical professionals and families through these crises.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Dr. Erin Bowen herself experienced the sudden unexpected death of a child—her 17-month-old son Conor—in 2016. In her family’s search for answers and support for their grief, she turned to the SUDC Foundation and found a mission. Click here to read Dr. Bowen’s own story.

The death of a child is devastating for everyone involved, including families and medical professionals alike. It defies the natural order of life that we expect. When the death is sudden and unexpected, families are overwhelmed with trauma, shock, and grief as the medicolegal death investigation begins.

Sudden unexplained death in childhood (SUDC) is the sudden and unexpected death of a child aged 12 months or older that remains unexplained after a thorough investigation including autopsy. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), SUDC affects approximately 400 children aged 1 to 18 years annually.

The death investigation system in our country is variable, comprising coroner and medical examiner systems in most areas. It is faced with challenges that include a lack of resources, a shortage of forensic pathologists, and, until recently, lack of procedural guidance, particularly for pediatric deaths. The lack of standardization for death investigation has far-reaching implications, including the resultant effects on the family as well as public health ramifications. Without standardization, accurate surveillance of these deaths is elusive.

Resources for pediatricians

Education regarding the death investigation system is limited in our pediatric training curriculum and, consequently, pediatricians may have difficulty providing appropriate guidance to families in the aftermath of these deaths. In sudden unexpected deaths of children aged 12 months and older, there is the additional challenge of minimal awareness of this category of death.

Although SUDC is the fifth-leading category of death in children aged 1 to 4 years, there is no targeted federal funding to support research. The SUDC Foundation (sudc.org) is the only organization whose mission is to promote awareness, advocate for research, and support those affected by the sudden loss of a child.

How new guidelines will help

In recognition of the need for consistency in approaching sudden pediatric deaths, the SUDC Foundation funded a grant for a collaboration between the National Association of Medical Examiners (NAME) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP). In January 2020, this expert panel of more than 30 multidisciplinary contributors from across the country published the first national consensus guidelines for sudden unexplained pediatric deaths: Unexplained Pediatric Deaths: Investigation, Certification and Family Needs. Available at sudpeds.com, the publication discusses the evolution of our understanding and practice in the area of pediatric death investigation; outlines procedural guidance for death investigation, autopsy, and ancillary testing as well as certification and reporting of these deaths; and promotes consistent classification of deaths in order to understand how often they occur.1

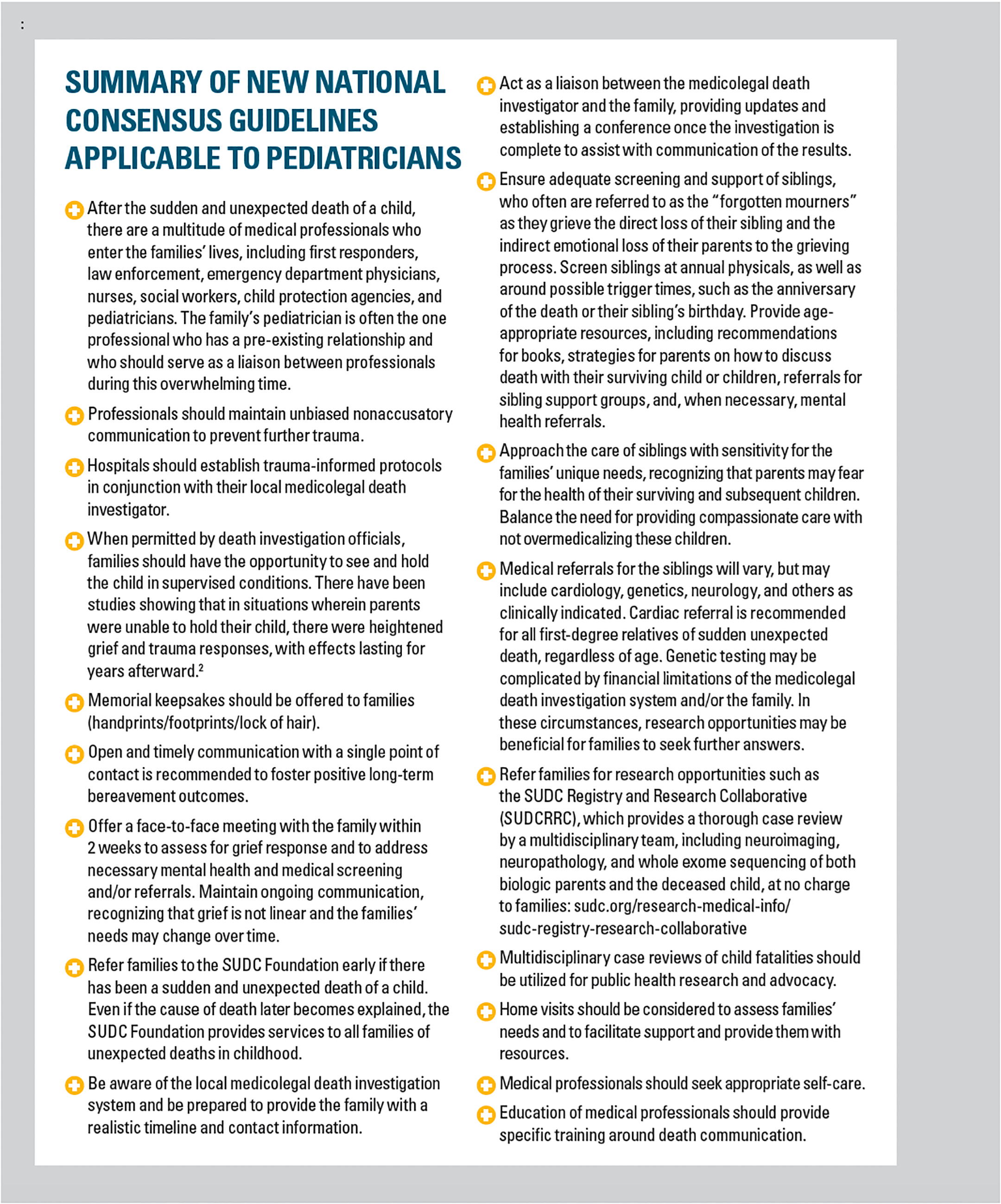

Summary of new consensus guidelines

There are also recommendations for prevention strategies and future research. Guidelines are provided for working with family members and other professional team members. The cornerstone of these guidelines is the provision of comprehensive and compassionate care, recognizing that the two are not mutually exclusive, but rather intimately connected for thorough investigations dedicated to high-quality care of survivors.

More research is needed

Currently, SUDC is unpredictable and unpreventable. For some families, the lack of explanation for their child’s death can be crippling. Although finding a cause does not mitigate their grief, in some cases it can allow them to better understand the death of their child and the implications for other family members. Pursuing appropriate medical screening may elucidate a cause for some of these deaths. However, we know that studies into the causes of sudden unexplained deaths in children aged older than 12 months are limited.

A recently published study from JAMA Network Open showed an increased rate of febrile seizures in these children. This is one area where future research could be helpful to better identify at-risk children. Similarly, the grief responses and needs of families after the death of older children have not been studied as extensively as infant death. With more research into these areas, we can build upon these guidelines to provide improved, data-driven approaches to the care for families affected by SUDC.

Although we may not be able to provide answers for all these deaths, we can ensure that we adequately support families after these tragedies and connect them with the appropriate resources. It is important to remember that your role as the child’s pediatrician does not end with their death.

In conclusion

Pediatric deaths are, thankfully, relatively rare. Consequently, pediatricians may feel ill equipped to manage the needs of bereaved families, particularly when these deaths are sudden and unexpected. Creating protocols that incorporate these new recommendations in conjunction with all the agencies and professionals involved can minimize confusion, prevent further trauma, and ensure optimal care for families during an already overwhelming and traumatic time.

References:

1. National Association of Medical Examiner’s Panel on Sudden Unexpected Death in Pediatrics; Bundock E, Corey T, eds. Unexplained Pediatric Deaths: Investigation, Certification and Family Needs. Academic Forensic Pathology International; 2019. https://sudpeds.com

2. Baker AM, Crandall L. To hold or not to hold. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2009;5(4):321-323. doi: 10.1007/s12024-009-9123-7