Gynecologic examination of the prepubertal girl

A gentle, patient approach is important when examining a prepubertal girl. Pay special attention to anatomic and pathophysiologic differences in the child. Emphasize setting the stage to make the examination a positive experience for your young patient.

Gynecologic examination of the prepubertal girl

By Jessica Annette Kahn, MD, and S. Jean Emans, MD

A gentle, patient approach is important when examininga prepubertal girl. Pay special attention to anatomic and pathophysiologicdifferences in the child. Emphasize setting the stage to make the examinationa positive experience for your young patient.

Gynecologic assessment of the prepubertal girl is an essential componentof preventive and diagnostic pediatric care. Routine gynecologic examinationof infants and children can help prevent future health problems such asvulvovaginitis by giving the clinician the opportunity to educate parentsabout perineal hygiene.1 During the annual genital inspection,the pediatrician also may discover such significant abnormalities as clitoromegaly,signs of early puberty, vulvar dermatoses, or rarely hymenal or vaginaltrauma. A more thorough gynecologic examination is warranted for the evaluationof vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, trauma, or pelvic pain. It is importantto be aware that the gynecologic examination can influence her future attitudetoward gynecologic care. Making the examination a positive experience, ifpossible, therefore is critical.2

Pediatricians are uniquely qualified to perform an appropriate clinicalassessment because of their expertise in examining young children and knowledgeof many anatomic and pathophysiologic conditions specific to children. Thepediatrician may have the additional advantage of already having built arelationship with the child who requires a gynecologic examination. Thisarticle focuses on setting the stage so that the examination is a positiveexperience for the patient and her family, describes specific techniquesand strategies for performing an appropriate and non-traumatic examination,and reviews diagnosis of disorders commonly found in prepubertal children.

Principles of gynecologic assessment

One of the most important principles to keep in mind when examining ayoung girl is to maintain her sense of control over the process. This canbe accomplished by establishing rapport with the child, keeping the paceunhurried, proceeding from less to more intrusive examinations and askingfor consent before proceeding, and allowing the child to be an active participantin the process as much as possible.2

Another important consideration when performing a gynecologic assessmentis providing anticipatory guidance to the patient and her parents. You canmodel for parents appropriate ways to discuss gynecologic issues with theirchild, and help parents and children understand the importance of discussingissues related to reproductive healthand sexuality during the prepubertalyears.1

Finally, issues of privacy and confidentiality are essential considerationswhen examining older children. Most young children will prefer to have aparent--usually their mother--in the room at all times. In some cases, however,it is helpful to spend time alone with the child during the interview, andto ask whether she prefers to be alone for the examination. When alone withan examiner, a child may disclose abuse or other concerns, and allowingher to be interviewed or examined alone may give her a greater sense ofcontrol and responsibility for her own health.

Taking the history

The history is critical in terms of making a diagnosis, but it also providestime for you to establish rapport with the patient and elicit her understandingof her symptoms and expectationsof the visit. Whenever possible, addressquestions directly to the child.

You can establish rapport by asking about psychosocial issues that mayimpact on the child's presenting gynecologic complaint, including familydynamics and peer relationships. Opening questions can include inquiriesabout the family structure and recent changes, school, friends (such aswhether she has a best friend), and the types of activities she enjoys.It is important to assess who cares for the child and to uncover--both fromthe parent and from the child--information about any history of sexual abuseor current concerns in that regard. Asking the child whether anyone hasever touched her in a way that made her feel uncomfortable often is helpfulin drawing out this information.

The medical history should be guided by the presenting complaint anddifferential diagnosis. If the issue is vaginal discomfort, pruritus, ordischarge, the differential diagnosis includes nonspecific or infectiousvulvovaginitis, vulvar skin disease, lichen sclerosis, and presence of aforeign body. Your questions should address the onset of symptoms; the type,frequency and timing of discharge; associated bleeding, pain, or pruritus;foreign body insertion; perineal hygiene; recent infections in the patientor her family (such as streptococcal pharyngitis or pinworms); recent antibiotictherapy; masturbation; and a history of sexual abuse.

If the issue is "vaginal" bleeding, the differential diagnosisincludes condyloma acuminatum, urethral prolapse, vascular lesions, precociouspuberty, hormonal medications, and (rarely) sarcoma botryoides, in additionto vulvovaginitis, foreign body, and lichen sclerosus. The history shouldassess the child's growth and development; signs of puberty such as breastdevelopment, axillary hair, pubic hair, growth spurt, and leukorrhea; genitaltrauma; vaginal discharge; and a history of foreign body insertion. A historyof behavioral changes and somatic symptoms, including recurrent or chronicabdominal pain, headaches, and enuresis, may signal abuse. Finally, it isimportant to remember that urethritis can cause dysuria or hematuria, whichmay be mistaken for vaginal bleeding. Urethritis can be caused by an infectiousagent, irritation, or trauma.

Past medical history should include information about congenital anomalies,systemic disorders with dermatologic manifestations, and growth and development.Congenital anomalies, and particularly renal anomalies, may be associatedwith gynecologic anatomic abnormalities. Many dermatologic disorders, suchas atopic dermatitis, seborrhea, and psoriasis, can manifest as vulvitisor vulvovaginitis. Abnormalities of growth and development can be essentialclues to precocious puberty or other systemic or congenital disorders.

Beginning the examination

After you have established a rapport with the child and taken her history,you should explain the gynecologic examination to both the child and herparent. This is an important step toward reinforcing the child's sense ofcontrol over the examination.

Explain to the child that the most important part of the examinationis "looking," and that it is important for her to communicatewith you during the examination. Tell the child that the examination willnot hurt, and if you are going to use instruments, that these tools areall specially designed for little girls.1Let the child look atand touch the instruments to be used, such as an otoscope or a hand lens.When talking with parents, it is important to carefully explain that thechild's hymen will not be altered in any way by the examination, becausemany parents do not fully understand the anatomy of the vagina and hymen.Basic diagrams of the anatomy may be helpful.

A parent or caretaker is usually present during the examination of ayoung child, and most children are comfortable with the parent sitting closeby or holding their hand. An older child should be asked whom she prefersto have in the room during the examination. Using a hand mirror can be usefulto promote education, distract a child, and allow her to participate moreactivelyin the examination. Your job will be easier if you adopt a relaxedand unhurried approach, which can help prevent anxiety in a child. If thechild is anxious, you may need to leave the room and return when she feelsready to be examined; in some cases, the procedure may have to be postponedfor several days. However, if the reason for the visit is urgent, such assignificant vaginal bleeding, and a child is uncooperative, you may haveto perform the exam under anesthesia.

Begin the procedure with relevant elements of the general pediatric exam,including height and weight and examination of the thyroid, neck, breasts,lungs, heart, and abdomen. Inspect the child's breasts and palpate themfor signs of puberty. Palpate the abdomen for masses and the inguinal areasfor a hernia or gonad. Tailor your gynecologic examination to the presentingissue. A complete examination includes inspection of the external genitalia,visualization of the vagina and cervix, and rectoabdominal palpation.

Examining the external genitalia

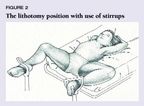

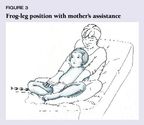

Most young children can be examined in the frog-leg position; that is,supine with knees apart and feet touching in the midline. Older childrencan be placed in adjustable stirrups (Figures 1 and 2). For a small childwho is fearful of the exam, it may be best to have the mother sit on thetable in a semireclined position (feet in or out of stirrups) with the child'slegs straddling her thighs (Figure 3).

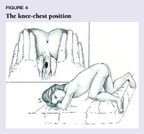

If you need to visualize the vagina and cervix and the child is olderthan 2 years, the knee-chest position may be useful. Have the child resther head to one side on her folded arms and support her weight on bent knees,which are six to eight inches apart. The child's buttocks will now be heldup in the air and her back and abdomen will fall downward (Figure 4). Usingthis position and an otoscope head for magnification and light, you willbe able to visualize the lower vagina, and usually the upper vagina andcervix, in 80% to 90% of prepubertal girls.3

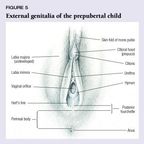

With the child supine, begin your external examination by inspectingher external genitalia (Figure 5). The child can assist you by holding herlabia apart. Inspect her for pubic hair and note the condition of the urethra,size of the clitoris, any signs of estrogenization, configuration of thehymen, and perineal hygiene. Newborns will exhibit maternal estrogen effects:the labia majora, labia minora, and clitoris will be relatively large, theepithelium a dull pink color, and the hymen often thick and redundant. Afterthe newborn period, the average size of a normal clitoral glans in a premenarchalchild is 3 mm in length and 3 mm in transverse diameter.4 Inprepubertal girls, the vaginal mucosa and perihymenal tissue will be moreatrophic and appear thin and red.

Visualizing the hymen. If you cannot fully visualize the hymen, ask thechild to cough or take a deep breath, or pull the labia gently forward anddown or laterally yourself so that you can see the hymen and the anteriorvagina. A hand lens or otoscope often is helpful. Classifications of hymenalconfiguration include posterior rim (crescent), annular, or redundant (Figures6 and 7).5 Congenital anomalies, including imperforate, microperforate,and septate hymen, also can occur.

In a microperforate hymen, it may be difficult to identify an opening.To establish its presence, try squirting a small amount of warm water orsaline with a syringe or angiocath, placing the girl in the knee-chest position,or probing with a small urethral catheter, feeding tube, or nasopharyngealCalgiswab moistened with saline or vaginal lubricant (Figure 8). If vaginalcultures are not needed, lidocaine jelly can be used to decrease the child'sdiscomfort. If you still cannot locate a hymenal opening, the child mayhave an imperforate hymen or vaginal agenesis. An imperforate hymen appearsas a thin membrane, and will bulge if hydromucocolpos is present. Vaginalagenesis is characterized by thick vestibular tissue, and often there isa dimple surrounded by a vulvar depression where the hymen should be.6

Acquired hymenal abnormalities usually are caused by sexual abuse andrarely by accidental trauma. Signs of acute trauma from sexual abuse includehematomas, abrasions, lacerations, hymenal transections, and vulvar erythema.These conditions usually resolve within ten to fourteen days. Signs of priorabuse can include hymenal remnants, scars, and hymenal transections. Findingson genital examination are normal, however, in most girls with a historyof substantiated sexual abuse. The significance of the diameter of the hymenalorifice is controversial; a large orifice may be consistent with a historyof sexual abuse, but it is not an absolute criterion.7,8

The vulva and anus. Next, examine the child's vulva and anus, observingfor hygiene, erythema, excoriation, labial adhesions, signs of trauma, andanatomic abnormalities. If extensive labial adhesions are present, you maynot be able to adequately examine the hymen and vagina and will need toreexamine the child after she has successfully completed treatment withlocal hygiene measures and topical estrogen (see Sidebar, "Common gynecologicfindings in the prepubertal girl").

Vulvitis and vulvovaginitis usually are characterized by vulvar rednessand irritation, which may be associated with vulvar discomfort, vaginaldischarge and odor, vaginal bleeding, dysuria, or pruritus. Common causesinclude dermatologic conditions, infections, irritants, and lichen sclerosis.The atrophic tissue of the prepubertal vulva is easily irritated, whichcan lead to nonspecific vulvitis. Harsh soaps, shampoos, bubblebath, poorhygiene, and tight or wet clothing (bathing suits) are common culprits.

Chronic vaginal discharge, which can occur with a vaginal foreign bodyor vaginitis, also can lead to vulvitis, which is characterized by an erythematous,hyperpigmented, or hyperkeratotic line along the dependent portion of thelabia majora.9 Clitoral erythema and pruritus often is a symptomof a prior or current vulvitis, and may be caused by adhesions between theclitoral hood and the glans clitoris. Treatment is the same as for labialadhesions. Lichen sclerosis also can present as vulvar discomfort or pruritus.It is characterized by atrophy of the vulvar skin, which may distort theanatomy of the labia and clitoris, producing ecchymoses and "bloodblisters."

A patient with signs of trauma, such as abrasions, lacerations, or contusions,should be evaluated for suspected sexual abuse. Viscous lidocaine and warmsaline for irrigation through an IV set-up may be helpful when examininga child who has an acute straddle injury and bleeding.

Examining the vagina

After you have examined the external genitalia, you should visualizethe vagina if the child complains of discharge or bleeding that may be vaginalin origin, or if you suspect a tumor, ectopic ureter, or vaginal foreignbody.6 In premenarchal girls, the vagina is 4 to 5 cm long withthin, red epithelium. In perimenarchal girls, the vagina is 8 cm long, andthe vaginal mucosa and hymen are thicker. Leukorrhea may be present.

The hymen and vagina usually can be seen adequately when a child is inthe supine position, with her legs flexed on her abdomen. For girls olderthan 2 years, the knee-chest position also permits excellent visualizationof the vagina and cervix without instrumentation.3 If necessary,an experienced examiner or pediatric gynecologist may use a small vaginoscope,cystoscope, hysteroscope, or flexible fiberoptic scope with water insufflationof the vagina to improve visualization.

These procedures are usually performed under anesthesia. Occasionally,a narrow vaginal speculum can be used in an older child who is well estrogenized.10,11

Dealing with a foreign body. If on vaginal examination you visualizea foreign body, you may be able to remove it with a cotton-tipped applicatoror by lavaging the vagina with saline or warm water after anesthetizingthe introitus with viscous lidocaine. Removal under anesthesia may be necessaryif a foreign body has become imbedded into the vaginal mucosa. The mostcommon foreign body encountered in prepubertal girls is a wad of toiletpaper, which appears as a small, gray mass.

Obtaining cultures. When a child has vaginal discharge or bleeding andthe source (such as a foreign body) is not obvious, obtain samples for cultureand saline preparation. If you suspect candidal vulvovaginitis, obtain apotassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; a Gram stain may be useful if thedischarge is purulent. Remember that this procedure can be painful to achild if you use a dry cotton swab or do not perform the examination gently.A better way of obtaining specimens from the prepubertal child is to usea nasopharyngeal Calgiswab moistened with nonbacteriostatic saline. Beforeinserting the Calgiswab, allow the child to feel a similar swab on her skin.If the Calgiswab does not touch the edges of the hymen, it should causethe child no discomfort. You can also ask the child to cough in order todistract her and cause her hymen to open.

A specimen for Chlamydia culture can be obtained by using a Dacron maleurethral swab and scraping the lateral vaginal wall gently. If you needmultiple samples, you can use a small feeding tube attached to a syringecontaining a small amount of saline to perform a vaginal wash and aspiration,or you can insert through the hymen a soft plastic or glass eyedropper with4 to 5 cm of IV plastic tubing attached.12 Another method ofobtaining samples, used by Pokorny and Stormer, consists of a catheter-in-a-cathetertechnique.13 The proximal end of an IV butterfly catheter isinserted into the distal end of a size 12 bladder catheter, and a 1-mL tuberculinsyringe with 0.5 to 1.0 mL of sterile saline is attached to the hub of thebutterfly tubing. The catheter is placed into the vagina, and the salineis injected into the vagina and aspirated. The device is commercially availableas the Pediatric Vaginal Aspirator from Cook Ob/Gyn (Spencer, IN.).

Culture for N gonorrhoeae should be plated on modified Thayer-Martin-Jembecmedium. Cultures for C trachomatis are recommended because of the possibilityof false-positive test results with indirect and slide immunofluorescenttests and insufficient data on tests that utilize polymer chain reactionand ligase chain reaction techniques. Cultures for other organisms shouldbe done by placing the Calgiswab into a transport Culturette II with medium,or by sending the aspirated fluid to the bacteriology laboratory for directplating. The bacteriology laboratory should plate the swabs on standardgenitourinary media, including blood agar, MacConkey, and chocolate media.If you send a culture for N gonorrhoeae and the results are positive, thelaboratory should identify the species unequivocally in a premenarchal girlbecause of the possibility of sexual abuse.

Examination of the vagina under anesthesia may be necessary if culturesdo not identify a pathogen, the child has a persistent discharge or bleedingand adequate examination is not possible, or you suspect a foreign body.Referral should be made to a gynecologist with experience in pediatric gynecology.

Rectoabdominal exam. After obtaining samples, perform a gentle rectoabdominalexamination with the patient either in stirrups or supine. This is especiallyimportant in girls who have persistent vaginal discharge, bleeding, or pelvicpain because it often is possible for an examiner to express vaginal discharge,palpate a foreign body, and detect masses. The child should be told thatthe examination will be similar to having her temperature taken or havinga bowel movement, and that a finger has a smaller diameter than a bowelmovement. After the newborn period, when the uterus is enlarged becauseof maternal estrogen effect, your examination should reveal a small, button-likecervix and uterus. Abdominal or upper pelvic masses that are palpable mayrepresent ovarian tumors. At the end of the examination, use your fingerto "milk" the vagina and assess for discharge or, very rarely,polypoid tumors.

Concluding the examination

After your examination is complete, congratulate the child for her cooperationand bravery. Discuss the results of the examination and your diagnosis andmanagement plan with the child and her parents after she is dressed. Thegynecologic examination of the prepubertal child can be challenging, butit can also be quite rewarding for a clinician who understands the uniqueanatomic and physiologic characteristics of a prepubertal child and approachesthe examination with patience, gentleness, and respect.

REFERENCES

1. Emans SJ, Lanfer MR, Goldstein DP: Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology,4th ed. Philadelphia, PA, Raven-Lippincott, 1998

2. Blake J: Gynecologic examination of the teenager and young child.Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 1992;19:27

3. Emans SJ, Goldstein DP: The gynecologic examination of the prepubertalchild withvulvovaginitis: Use of the knee-chest position. Pediatrics 1980;65:758

4. Huffman JW, Dewhurst CJ, Capraro VJ: The Gynecology of Childhood andAdolescence. Philadelphia, PA, WB Saunders, 1981

5. Pokorny SF: Configuration of the prepubertal hymen. Am J Obstet Gynecol1987;157:950

6. Gidwani GP. Approach to evaluation of premenarcheal child with a gynecologicproblem. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1987;30:643

7. Emans SJ, Woods ER, Flagg NT, et al: Genital findings in sexuallyabused symptomatic and asymptomatic girls. Pediatrics 1987;79:778

8. McCann J, Wells R, Simon M, et al: Genital findings in prepubertalgirls selected for nonabuse: A descriptive study. Pediatrics 1990;86:428

9. Pokorny SF. Prepubertal vulvovaginopathies. Obstet Gynecol Clin NorthAm 1992;19:39

10. Pokorny SF. The genital examination of the infant through adolescence.Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 1993;5:753

11. Capraro VJ: Gynecologic examination in children and adolescents.Pediatr Clin North Am 1972;19:511

12. Capraro VJ, Capraro EJ: Vaginal aspirate studies in children. ObstetGynecol 1971;37:462

13. Pokorny SF, Stormer J: Atraumatic removal of secretions from theprepubertal vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987;156:581

SIDEBAR: Common gynecologic findings in the prepubertal girl

Vulvovaginitis and vaginal bleeding often are found on gynecologic examinationof prepubertal girls. Labial adhesions, also common, usually are asymptomaticand are more likely to be noticed by a parent or found on routine pediatricexamination.

The history and examination usually clinch the diagnosis of vulvovaginitisand vaginal bleeding, but selected laboratory tests such as culture arehelpful in some cases. The history should include the quality of the discharge(color, odor, presence of blood), hygiene, medications, irritants such assoaps and bubble bath, anal pruritus, enuresis, the possibility of a foreignbody or sexual abuse, any recent infections, and a history of systemic ordermatologic conditions. Questions about caretakers, behavioral changes,fears, and somatic symptoms may help to diagnose sexual abuse.

As described in detail elsewhere in this review, the physical exam shouldinclude an inspection of the perineum, vulva, hymen, and anterior vagina.Visualization of the vagina and cervix and rectoabdominal examination alsois necessary if a child has persistent discharge, bleeding, pain, or ifyou suspect presence of a foreign body. Tables 1 and 2 list the differentialdiagnoses of vulvovaginitis and vaginal bleeding.

Vulvovaginitis

Vulvitis, or vulvar inflammation, can occur alone or in combination withvaginitis, or vaginal inflammation. Risk factors for vulvovaginitis in theprepubertal child include hypoestrogenism, which can lead to an atrophicvaginal mucosa; close proximity of the vagina and anus; lack of protectivehair and labial fat pads; poor hygiene; use of irritants such as bubblebath; and contact with nonabsorbent clothing. Clinical manifestations includepruritus, vaginal discharge and odor, vaginal bleeding, dysuria, and vulvarredness and irritation.

Nonspecific vulvovaginitis. Nonspecific vulvovaginitis often is associatedwith an alteration in vaginal flora, which may be due to a change in theaerobic flora or overpopulation with fecal aerobes and anaerobes. Vaginalcultures will reflect normal flora, including lactobacilli, Staphylococcusepidermidis, diphtheroids, Streptococcus viridans, enterococci, and enterics(Streptococcus faecalis, Klebsiella species, Proteus species, Pseudomonasspecies).

Specific vulvovaginitis. Vulvovaginitis also may be associated with aspecific infectious agent. Bacterial causes include group A, b-hemolyticStreptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Branhamellacatarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitidis, and Shigella.Sexually transmitted infections include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydiatrachomatis, herpes simplex virus, Trichomonas, and human papillomavirus.It is important to note that these organisms also can be vertically transmittedat birth and herpes can be transmitted by nonsexual contact. N gonorrhoeaerarely persists beyond the newborn period without symptoms. Thus, a positivevaginal culture should be considered evidence of sexual abuse in the child.Likewise, C trachomatis rarely persists beyond age 2 to 3 years, and mostinfants and toddlers have been treated since birth with an antibiotic thatwould treat Chlamydia. Therefore, a positive culture from the vagina ina 5-year-old requires reporting and evaluation for child sexual abuse. Thefinding of genital herpes type 2 is a strong indication of sexual abuse.Coexisting primary oral and genital herpes type 1 may occur in young children,but a finding of type 1 in the genital area alone should prompt an evaluationbecause this is more likely to be acquired by abuse.14Trichomonaswill rarely cause symptoms in the newborn period and spontaneously resolveswith waning of estrogen levels. New onset of Trichomonas vaginitis in theprepubertal child is associated with sexual abuse. HPV is also verticallytransmitted and lesions may appear in the first few years of life. However,new onset of genital warts in the older prepubertal child is associatedwith sexual contact.

Candidal infection is uncommon in prepubertal children unless there isconcomitant antibiotic use, diabetes, immunosuppression, or occlusive diaperuse. Typical findings are a maculopapular brightly erythematous rash withsatellite papules.

Finally, pinworms may present as perineal or perianal pruritus, witherythema and often excoriations in the perirectal area. Diagnosis can befacilitated by performing the tape test: press a piece of cellophane againstthe child's perineum in the morning, affix the tape to a slide, and examineit under the microscope for the characteristic eggs. Adult pinworms maybe visible at night.

Noninfectious causes of vulvovaginitis also are common. Vaginal foreignbodies, particularly wads of toilet paper, often are found in girls whohave a bloody, foul-smelling, or persistent vaginal discharge. Vaginal orcervical polyps or tumors also can present with symptoms of vaginitis.

Systemic illnesses that can cause vulvovaginitis include measles, varicella,scarlet fever, mononucleosis, Kawasaki disease and Crohn's disease. Vulvarskin disorders are common, and often easily recognizable on exam. Seborrheicdermatitis is characterized by erythema of the vulva, often associated withyellow scales and crusting. Seborrhea also is commonly found on the scalp,behind the ears, and in the nasolabial folds. Children usually are asymptomatic,but they may present with secondary infection.

The rash of atopic dermatitis is typically maculopapular, pruritic, anderythematous. Excoriations are common, and lesions in other areas of thebody or a history of allergy or atopy may help in making the diagnosis.Psoriasis, scabies, and autoimmune bullous diseases also can present asvulvovaginitis. Lichen sclerosus may present as vulvar discomfort or pruritus.It is characterized by atrophy of the vulvar skin, which causes the labiaand clitoral hood to appear thin, white, and parchment-like. The atrophymay distort the anatomy of the labia and clitoris. Other findings includeecchymoses and "blood blisters," which often develop after mildtrauma such as riding a bicycle.

Other associations.Vaginal complaints also can be associated with masturbationor psychosomatic illness, or they may be factitious. Physiologic leukorrheacan be confused with vulvovaginitis. Newborns and pubescent girls sometimeshave significant vaginal secretions because of estrogen effect. The dischargeis usually white and not malodorous, and wet preparation demonstrates multipleepithelial cells without polymorphonuclear cells. Urethral lesions alsoshould be considered. An ectopic ureter can present as persistent wetnessor purulent discharge.

Urethral prolapse, a mucosal inversion at the urethral meatus, may beasymptomatic but it also can become inflamed and cause dysuria, perinealdiscomfort, and bleeding. It may appear as a brightly erythematous, annular,periurethral mass (see figure "A").

In girls with persistent, purulent, or recurrent vaginal discharge, orthose with a suspicion of sexual abuse, obtain a wet preparation and culturesfor bacterial pathogens, C trachomatis, and N gonorrhoeae. A KOH preparationor Biggy agar culture is useful to rule out candidal infection. A tape testmay be useful for suspected pinworm.

Managing vulvovaginitis. A girl who has nonspecific vaginitis shouldbe counseled to do the following: (1) practice good perineal hygiene; (2)urinate with her knees spread apart; (3) wear white cotton underpants andloose clothing; (4) take sitz baths once or twice a day; (5) avoid irritantssuch as bubble bath and use hypoallergenic soaps; and (6) apply a barrierointment such as A and D, Vaseline, or Desitin to the perineum. If the child'ssymptoms of vulvovaginitis persist, you should review your diagnosis. Forunusually persistent cases, it is appropriate to prescribe a 10-day trialof antibiotics (amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, or a cephalosporin)or occasionally a two- to three-week course of an estrogen cream. If youidentify a specific pathogen, appropriate antibiotic therapy is indicated,in addition to the measures previously described.

If you identify and remove a foreign body, recommend that the child takesitz baths for two weeks. Treatment of lichen sclerosus consists of eliminationof irritants, improved hygiene, application of barrier ointments, and administrationof oral hydroxyzine hydrochloride before bed to minimize scratching. Forpersistent cases, prescribe a one- to three-month course of a low-potencytopical steroid preparation, such as hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5%, followedby careful hygiene and use of emollients. If a child's symptoms are severe,a one- to four-week course of a moderate-potency ointment can be recommended,followed by a lower-potency preparation. In severe cases, clobetasol (Temovate)may be useful, applied twice daily for two weeks and then gradually taperedover the next several weeks, but this requires expertise and careful supervisionwith frequent follow-up. Urethral prolapse often resolves after treatmentwith topical estrogen cream twice daily and sitz baths, but surgical excisionmay be required if there is necrosis.

Vaginal bleeding

Genital bleeding should always be assessed thoroughly. The source maybe the vulva, vagina, endometrium, and occasionally the urethra. A carefulhistory is important; a history of hormonal medications or signs of precociouspuberty may suggest the cause of the bleeding. A history of trauma--whetheraccidental, intentional (for example, scratching due to pinworm infection)or caused by sexual abuse--also should be elicited. Vaginal foreign bodiesare a common cause of bleeding, but children often are reluctant to admitto foreign body insertion.

Vaginal bleeding is also associated with vulvovaginitis. Group A streptococciand Shigella are the most common causes. Endocrinologic issues, such asneonatal bleeding due to maternal estrogen withdrawal, precocious puberty,exogenous hormone preparations, and hypothyroidism should be ruled out.Dermatoses such as lichen sclerosus can cause bleeding. Condylomata acuminataalso can cause bleeding but may be difficult to recognize, because in prepubertalchildren, they often do not have the typical cauliflower-like appearance.Rather, genital warts typically present as exophytic lesions or papuleswith small red punctations over the surface.

Urethral prolapse also can present with bleeding. Although rare, it isimportant to recognize sarcoma botryoides, or embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma.Such a tumor can present as a lower abdominal mass or as vaginal bleedingor passage of part of the tumor. The typical location is the anterior vaginalwall near the cervix. Finally, trauma, either accidental or due to sexualabuse, may cause significant bleeding. Sources of accidental trauma areusually straddle injuries.

The work-up for vaginal bleeding includes a careful inspection of thevulva and vagina, wet preparation and bacterial cultures, and cultures forsexually transmitted infections if indicated. If the bleeding is unexplainedor you suspect a foreign body or tumor and the vagina cannot be fully visualized,an exam under anesthesia by a gynecologist is necessary. Management is dictatedby the diagnosis: antibiotics and hygiene measures for infectious vulvovaginitis,surgical repair of trauma if necessary, biopsy of polyps or suspected tumors,removal of foreign bodies, further investigation for sexual abuse if itis suspected by exam or history or if condylomata are found, sitz bathsand estrogen cream for urethral prolapse, and further investigation

into the etiology of precocious puberty.

Labial adhesions

The extent of labial adhesions and associated symptoms are variable (seefigure "B"). Symptoms of vulvovaginitis can occur if an adhesionis extensive enough to cause pooling of urine above the agglutinated tissue.If that is the case, a child may have symptoms of urethritis or a historyof urinary tract infections. In determining the diagnosis, it may be helpfulto inquire about persistently wet underwear, recurrent fevers, unexplainedUTI, and abdominal or lower back pain.

Observation alone is appropriate for small adhesions. Treatment for extensivelabial adhesions is topical estrogen cream applied along the adhesion withgentle pressure twice a day for three weeks, then at bedtime for three weeks.Once the adhesion has resolved, a barrier ointment should be used to preventrecurrence. Occasionally, an adhesion will require separation, which canbe done either in the office or under anesthesia. Referral to a gynecologistis warranted if a child has an acute urinary retention or persistent completeadhesions not responding to office therapies.

DR. KAHN is Assistant in Medicine, Children's Hospital, Boston, and Instructor in Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

DR. EMANS is Chief, Adolescent Division, Children's Hospital, and Associate Professor of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Having "the talk" with teen patients

June 17th 2022A visit with a pediatric clinician is an ideal time to ensure that a teenager knows the correct information, has the opportunity to make certain contraceptive choices, and instill the knowledge that the pediatric office is a safe place to come for help.

Artificial intelligence improves congenital heart defect detection on prenatal ultrasounds

January 31st 2025AI-assisted software improves clinicians' detection of congenital heart defects in prenatal ultrasounds, enhancing accuracy, confidence, and speed, according to a study presented at SMFM's Annual Pregnancy Meeting.