Herpetic Lesions Primary Herpetic Stomatitis Herpetic Whitlow Recurrent Herpes in Uncharacteristic Locations

A 3-year-old boy with high fever, malaise, anorexia, and drooling of 3 days' duration was brought to the emergency department (ED). A bacterial throat infection was diagnosed, and oral antibiotic therapy was started.

Herpetic Lesions

A 3-year-old boy with high fever, malaise, anorexia, and drooling of 3 days' duration was brought to the emergency department (ED). A bacterial throat infection was diagnosed, and oral antibiotic therapy was started.

After 3 days, the child was brought back to the ED with a fever, which had remained high despite treatment, and multiple shallow ulcerations on the gums, tongue, and soft and hard palate (A and B). He was fussy and mildly dehydrated. His gums were swollen and bled easily. He also had dried blood on his teeth and halitosis.

This child has primary herpetic stomatitis, the first infection of oral tissues with herpes simplex virus (HSV). Most children acquire their initial infection through direct contact (eg, a kiss from a parent with an active, primary, or recurrent lesion, as in this child's case). Previously infected persons may shed the virus intermittently in their saliva and serve as a source of infection even without active lesions. For this reason, the actual source of the infection is often unidentified.

Almost all adults have had a primary herpetic infection. More than 90% of adults show serologic evidence of past infection with HSV-1. The virus remains latent for life and may periodically reactivate in the lips, oral mucosa, or other skin sites of some persons.

Most primary HSV-1 infections are subclinical. Patients may have nonspecific symptoms, such as cervical lymphadenopathy, malaise, and low-grade fever, without discrete clinical lesions. Primary herpetic stomatitis develops in about 5% to 10% of patients initially infected with HSV. These patients have multiple, discrete, superficial ulcers of about 1 to 3 mm throughout the oral cavity on both mobile (buccal and labial) and attached (gingival and hard palate) mucosa. The oral lesions begin as vesicles that rupture easily during talking and eating and thus are rarely seen clinically.

The diagnosis of primary herpetic stomatitis is often based on the clinical history and presentation. When needed, cytologic smears of intact or recently broken vesicles may demonstrate epithelial giant cells with intranuclear eosinophilic viral inclusions, typical of herpes viral infections.

Symptoms generally last 1 to 2 weeks.This patient was treated with an analgesic/antipyretic medication. An antiviral agent given within 48 hours of the first symptoms can potentially shorten the duration of the illness.

Tell the parents of children with primary herpetic stomatitis that herpetic whitlows can develop in young children who bite their cuticles or suck their fingers. Providing information about HSV infection can be helpful, even though not much can be done in the way of prevention(Box). *

Herpetic Whitlow

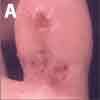

Primary herpetic stomatitis was diagnosed in a 5-year-old girl who presented with high fever, swollen gums, and mouth sores. Five days later, she returned with lesions on the right big toe, which was swollen and tender (A). The lesions appeared 3 days earlier as grouped blisters on an erythematous base; some had crusted. Careful questioning revealed that the child habitually puts her fingers and toes in her mouth and bites her cuticles. On examination, the patient still had herpetic lesions in the oral cavity. She had no lesions on the fingers. Epitrochlear and axillary nodes were normal.

Herpetic lesions of the finger (B and C) are caused by autoinoculation from primary oral lesions through exposure to infected saliva via a break in the skin--commonly as a result of cuticle biting or finger sucking. The affected fingers (and very rarely toes) are often exquisitely tender and quite edematous. In contrast, the pulp space of a felon is usually more intensely swollen than that of a herpetic whitlow.

The characteristic grouped, 1- to 3-mm, vesicular lesions and surrounding erythema may develop within 1 to 2 weeks after inoculation. Initially, the patient may feel a burning or tingling in the affected area. Fever and malaise may precede the lesions. The vesicles typically contain a clear, yellow, sometimes bloody fluid and may ulcerate or rupture. Lymphangitis and epitrochlear and axillary lymphadenopathy are not uncommon.1 The infection can progress to the subungual space. After 10 to 14 days, symptoms usually abate considerably, and the lesions crust and heal completely during the next 5 to 7 days.

Like other herpes infections, herpetic whitlows are characterized by a primary infection that may be followed by a latent period with recurrences.1 After the initial infection, which is usually the most symptomatic, the virus enters cutaneous nerve endings and migrates to the peripheral ganglia and Schwann cells, where it lies dormant.1 In up to half of patients, recurrences are often milder and shorter in duration.1

Recurrent Herpes in in Uncharacteristic Locations

Also known as cold sores or fever blisters (A), recurrent herpes labialis is usually diagnosed without difficulty.

Herpes labialis is common. About 20% to 40% of persons report having had cold sores at some time. Triggers of cold sores, such as physical trauma, sun exposure (UV light), menstruation, emotional stress, and illness, can be identified in some patients who are otherwise healthy. The clinical lesions tend to recur at the same sites, usually at the mucocutaneous junction, with the same characteristics.

Always think of herpes when you see grouped vesicles on an erythematous indurated base. Most cold sores in children are caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1. Clinically, cold sores caused by HSV-1 are indistinguishable from those caused by HSV-2. Patient age, location of the lesions, and history of suspected child abuse may point to one type of HSV over the other. In a classic recurrent case, laboratory evaluation may be unnecessary; however, it may be useful in some pediatric patients at initial diagnosis.

When the inoculation of HSV-1 occurs in an uncharacteristic location--for instance, on the earlobe (B); under the lower eyelid (C); on the cheek in a child with herpes conjunctivitis (D); or in the philtrum and nares (E)--herpes lesions can be mistaken for impetigo or cellulitis. Unlike mucocutaneous HSV infection, cutaneous HSV infection rarely recurs. Often, patients have a history of cold sores. The lesions appear and behave in a similar way to cold sores.

For patients who have occasional herpes infections, no treatment is indicated. For those who have frequent or severe recurrences, prophylaxis with oral acyclovir can help prevent or shorten the duration of an episode. Prophylaxis can also be given for a few days before and after a known trigger, such as menstruation, sun exposure, facial surgery, or stressful event (eg, dental appointment, wedding).

References:

REFERENCE:

1.

Omori M. Herpetic whitlow. eMedicine Web site. Available at:

http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic754.htm

. Accessed October 12, 2006.