How to identify warning signs in suicidal youth

Pediatricians are in a unique position to identify risk factors for suicide and provide anticipatory guidance and interventions to patients and families.

Michael A. Shapiro, MD

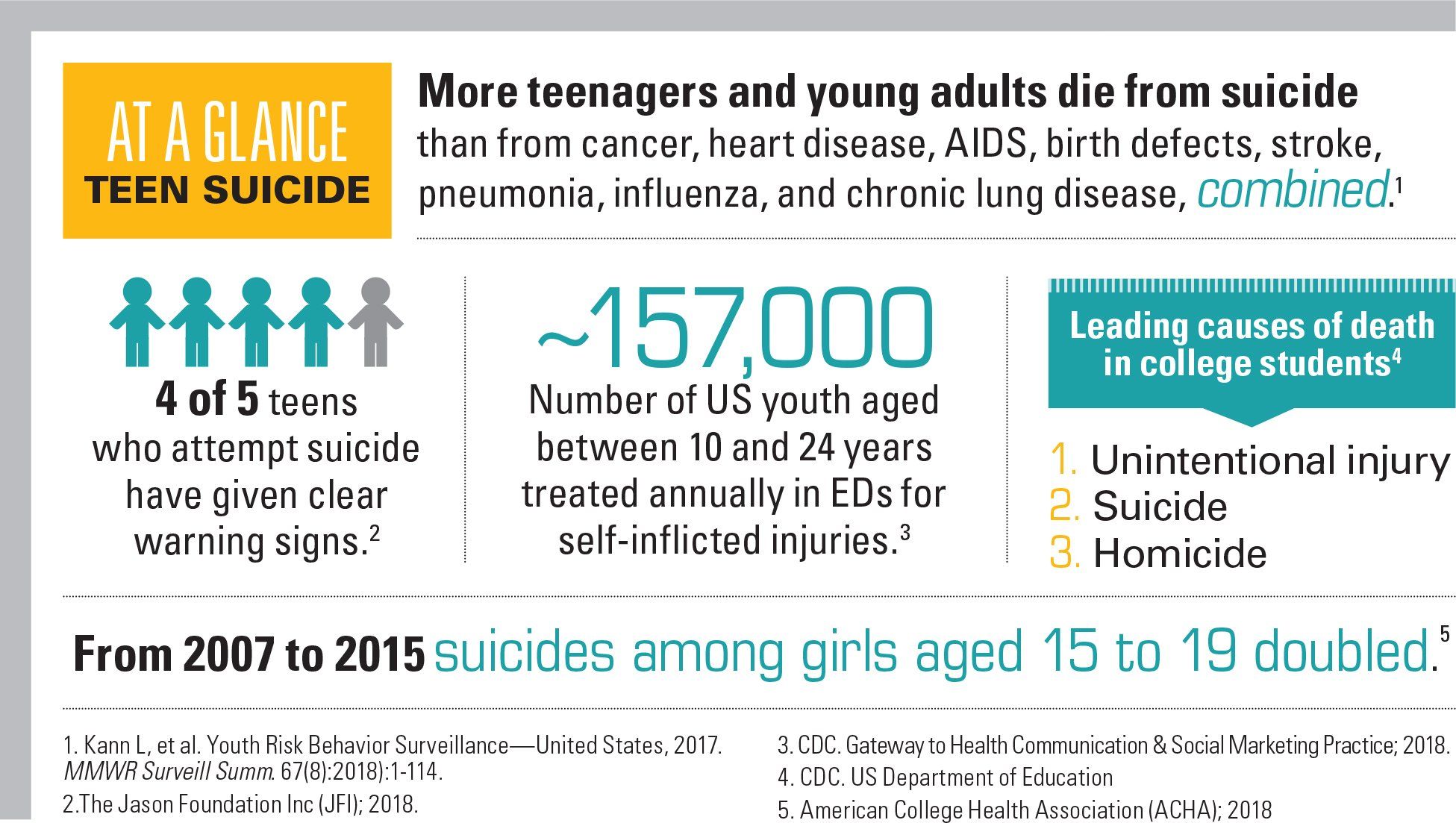

At a Glance: Teen Suicide

Elizabeth Ballard, PhD

The rate of youth suicide has been rising yearly for more than a decade. By recognizing individuals at risk and providing anticipatory guidance, interventions, and referrals, pediatricians are well positioned to help reverse this trend, said Michael A. Shapiro, MD, at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) 2018 National Conference and Exhibition in Orlando, Florida.

Shapiro is assistant professor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Florida (UF), and clinical director, UF Health Child Psychiatry and Psychology Clinic-Springhill, Gainesville, Florida. He formerly was medical director of the Adolescent Inpatient Unit at UF Health Shands Psychiatric Hospital, Gainesville.

On November 3, in a session titled “Suicide risk in youth,” Shapiro discussed the scope of the problem of youth suicide, outlined ways to identify those at risk, and provided advice on effective communication style and acute management.

“Pediatricians are not expected to fill the role of a child psychiatrist or psychologist, but they need to know which youth are at risk, when to refer to a mental health specialist, and how to talk to kids and parents about suicide. Pediatricians are usually the first health professional that a depressed or suicidal youth will confide in,” says Shapiro.

Recognizing risk factors

The increasing rate of suicide in the pediatric population is occurring across all demographic groups, but it has been increasing particularly in the black community and in the 10- to 14-year-old age group. Certain social history findings are also associated with increased risk, including homelessness; being in child welfare, foster care, or juvenile justice systems; being a victim of abuse or bullying; and identifying as a gender/sexual minority (LGBTQ).

“Low connectedness with parents or poor family interaction is a common theme in these risk groups and something to watch for,” Shapiro says.

He notes that having a parent with depression is also a significant risk factor that should be explored but something that pediatricians might not think to ask about.

In addition, Shapiro emphasizes that professionals may have to treat suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) as unique problems in addition to depression. “Although there are some shared risk factors, suicide and NSSI appear to have distinct risk factors, and some cases of suicide occur outside of depression,” Shapiro says.

Screening and management

Clinicians can screen patients for suicide risk by asking a series of questions that become more intrusive with each affirmative response. To start the questioning, older children can be asked, “Do you ever get so upset that you wish you were dead?” Because younger children may not know what “dead” means, they should be asked instead about wishing they could disappear or go away. Positive responses can lead to further questions. “Pediatricians should not worry that asking questions to screen for suicide will lead to suicide thoughts or attempts,” Shapiro points out.

In his session, Shapiro also discussed the utilization of evidence-based suicide risk assessment tools, including the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) that can be downloaded for no cost online (http://cssrs.columbia.edu).

In addition, Shapiro reviewed elements to include in a safety plan that suicidal youth and their families can use in the event of a suicidal crisis. He cautioned not to ask patients to enter into a “no-harm” contract. “No-harm contracts do not work and might hinder the individual’s willingness to share concerns should he or she have a problem in the future,” Shapiro cautions.

“Prescribing an antidepressant medication is also not a solution for acute management of suicide risk,” he says.

Commentary

Suicide rates in children and adolescents have increased over the last decade. Particularly concerning are recent increases in 10- to 14-year-olds. As many suicidal youth are not seen by mental health professionals, pediatricians often are the first line for identification and management of at-risk patients. Therefore, it is essential that pediatricians are informed about the potential risk factors and management strategies for young persons at risk for suicide.

In his session “Suicide risk in youth” at the AAP’s 2018 National Conference, Dr. Michael Shapiro details the role of the pediatrician in suicide prevention. One key message is the importance of screening. As Dr. Shapiro states, there is no evidence that asking about suicide will lead to thoughts about suicide. In fact, in interviews with children with and without psychiatric diagnoses, youth overwhelming support screening in nonpsychiatric settings.

Many adolescents seen by pediatricians will know someone with a mental health concern even if they do not experience symptoms themselves. Screening by a pediatrician can be one method of normalizing discussions on mental illness and suicide risk to reduce stigma.

As mentioned by Dr. Shapiro, the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) is one method of screening. The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit, which was developed at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), is publicly available (www.nimh.nih.gov/labs-at-nimh/asqtoolkit-materials/index.shtml) for professionals in medical settings who want to screen for suicide risk. Helpful resources for following up on positive responses to screening items are also available on the same online site.

Suicide prevention is not limited to only psychiatrists and psychologists and requires everyone in the healthcare system-pediatricians, nurses, social workers, and mental health professionals alike-working together to help at-risk youth.

Elizabeth Ballard, PhD, is a clinical psychologist and director of Psychology and Behavior Research and also director of Predoctoral Training in the Experimental Therapeutics and Pathophysiology Branch of the Intramural Program at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), Bethesda, Maryland.