How pediatricians can help mitigate the mental health crisis

Now that major medical organizations have declared a youth mental health crisis, what can pediatricians do to advocate for change?

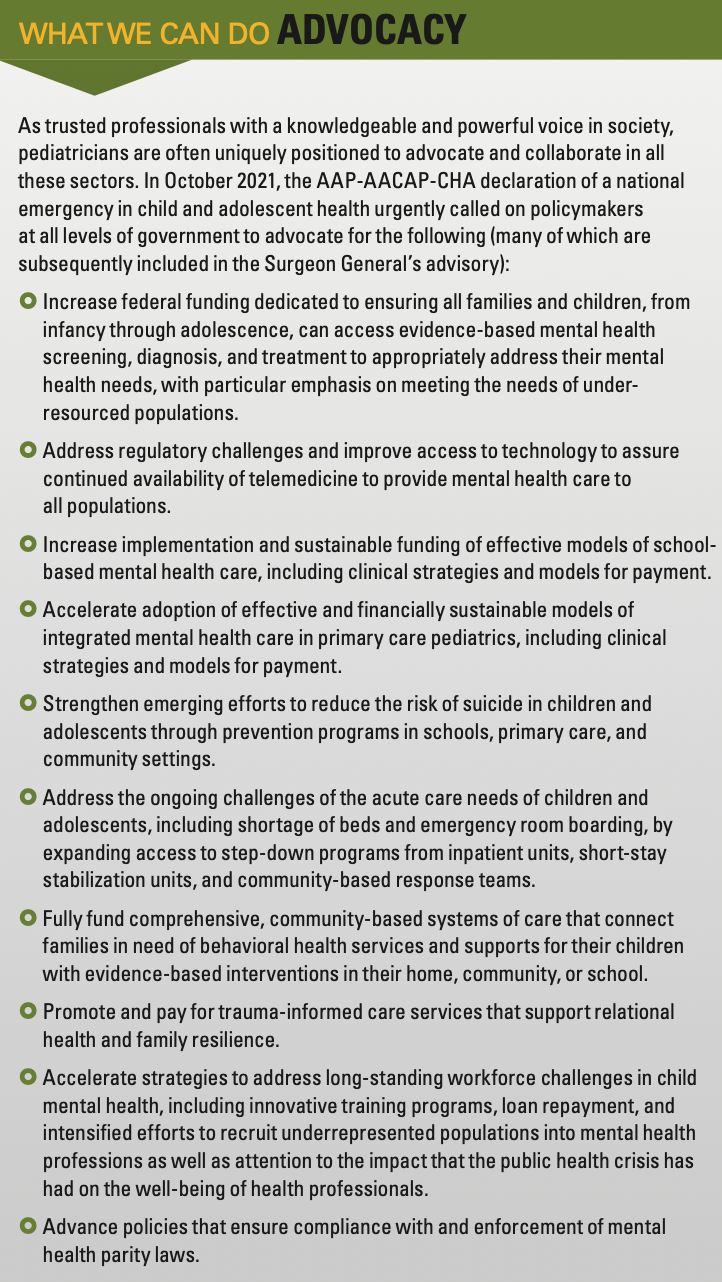

This past October, a declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health was published jointly by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), and the Children’s Hospital Association.1 Soon after, in December 2021, Vivek Murthy, MD, the US surgeon general, issued an advisory on the youth mental health crisis.2 Both documents recognize the magnitude of this crisis, highlight the urgency of action and advocacy, and provide a framework for moving the needle that involves all sectors of society.

What we can do: General pediatricians

How did we get here, and what roles can we play in the pediatric community to enhance our capacity to identify and address mental health in youth and advocate for effective, sustainable models of care? How can we as pediatricians step up to Murthy’s call to engage with all the “institutions that surround young people and shape their day-to-day lives—schools, community organizations, health care systems, technology companies, media, funders and foundations, employers, and government?”2

How did we get here?

All children are exposed to stressors that can affect mental health in the short term. Some children go on to have mental health conditions, and the likelihood is affected by genetics, epigenetics, and ongoing environmental factors. Just as traumatic or stressful events and experiences can increase the risk, strong and supportive relationships and institutions can offset or mitigate that risk. Moreover, if mental health conditions do develop, early and ongoing recognition and treatment can decrease associated morbidity.2-4

The 2019-2020 National Survey of Children’s Health showed that 23% of children aged 3 to 17 years have a reported mental, emotional, developmental, or behavioral (MEDB) problem, with prevalence unevenly distributed by geographic area and social determinants of health: Forty percent of children with 2 or more adverse childhood experiences have an MEDB problem compared with 16% without an adverse experience. Children from households with an income of less than 100% of the federal poverty line are 40% more likely to have an MEDB problem than those living in wealthier households.

What we can do: Advocacy

The decade preceding the pandemic saw a breathtaking increase in poor mental health in youth. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey Surveillance Data Summary and Trends Report: 2009-2019 shows worsening trends in most areas of mental health in high school students. In 2019, 37% experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness and 19% seriously considered attempting suicide, a 40% and 36% increase from 2009, respectively. Vulnerable youth suicide rates in children and young adults aged 10 to 24 years increased 57% between 2007 and 2018,6 but the rates have since stabilized and even slightly declined in 2020.7

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated mental health conditions for many children for a myriad of reasons: missed or delayed opportunities for learning, socialization, sports, activities, celebrations, and marking milestones; direct stress related to COVID-19 illness, avoiding COVID-19, and protecting loved ones; and ongoing economic distress, to name a few. Beginning in April 2020, the proportion of mental health–related visits in pediatric emergency departments increased significantly for both children and adolescents.8 A 2021 report from the Child Mind Institute, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children’s Mental Health: What We Know So Far,” highlights the disproportionate negative impact on vulnerable children: those with preexisting mental health problems, especially those with limited access to treatment, racial minorities experiencing racism in the health care system and beyond, LGBTQ+ children, and families living with economic uncertainty or food insecurity.4

Skill-building resources

To mitigate the level of need that has created the current crisis, it is particularly important that emerging mental health symptoms be recognized and addressed early within the pediatric medical home before they escalate to the level of crisis. Historically, however, mental health care has not been a substantial part of pediatric residency training, leaving many pediatricians feeling unprepared to care for the mental health needs of their patients. Many resources now exist, and more are being developed every year, to help pediatricians gain the knowledge and skills to care for patients’ mental health needs.

What we can do: Pediatric subspecialists

For example, the AAP has developed a mental health toolkit for pediatricians that includes materials, real-world cases, tools for screening, video examples of skills, and an algorithm serving as a cognitive map for how to approach mental health concerns in an outpatient office setting.9 Another resource, The REACH Institute, offers live and online evidence-based training courses for pediatricians on identification and treatment of mental health issues, including screening, medication management, cognitive behavioral therapy, and a host of other topics, all patient-centered and designed to be feasible in an outpatient office setting.10 (For more on The REACH Institute and pediatrician training, see “Guiding principles in managing pediatric mental health issues”) Alternatively, many health systems also offer continuing medical education courses on mental health care for primary care providers, and several state insurers offer training along with mandates for mental health screening.

What we can do: Pediatric trainees and training programs

In addition to building their own skills, pediatricians are in a unique position to partner with patients to build family skills. Tools such as positive parenting, behavioral strategies, and healthy attachment are essential to helping patients and families build resilience and helping children learn to work through difficult emotions.3,11 Pediatricians can encourage parents and caregivers to address their own mental health and substance use conditions, as well as model for their children responsible social media use and healthy responses to life stressors.1

Enhanced screening, integrated care teams, and CPAP

The Surgeon General’s advisory includes key areas of practice enhancements and health systems transformation that have a strong evidence base. These recommendations highlight the critical mental health provider shortage as well as the expanding role of pediatric providers in mental health care. Several resources are available to help practices begin screening for mental and behavioral health concerns (for more on screenings, see “Screening adolescents for psychosocial concerns”), social determinants of health, and adverse childhood events per the AAP Bright Futures guidelines.12,13 The AAP also offers a resource to help pediatricians identify tools that best fit their practice.14 It is important to build a prevention-focused model of care, including trauma-informed principles that address the needs of children and caregivers who have faced adversity. For example, a primary prevention model such as Zero to Three’s Healthy Steps integrated team model focuses on positive parenting and parental well-being and on addressing social determinants of health within the primary care visit.15

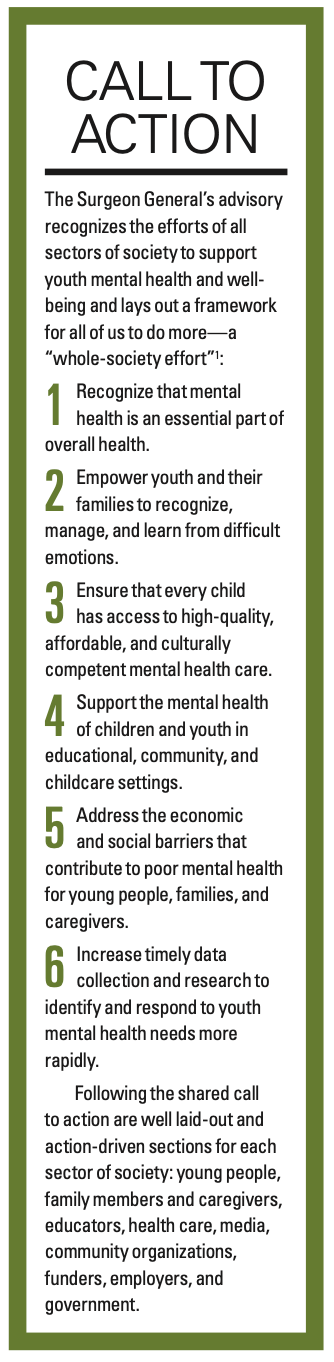

Call to action

Another way pediatricians can build skills while ensuring a more secure safety net for patients is to partner with local mental health providers. Several models of these partnerships have emerged in the past decade, including integrated clinic models and state-run phone consult services. Pediatric practices can establish a variety of integrated care models16 from colocated care to truly collaborative care.17 Integrated clinic models bring mental health providers into the primary care setting, improving access to care for patients and increasing collaboration between mental health and primary care providers. Not only can these models decrease potential barriers for patients in accessing mental health care, they also offer a unique opportunity for mental health and primary care providers to learn skills from one another, providing a more consistent circle of care for patients. Many states now support pediatric mental health phone consult services modeled after the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP), the original CPAP, which provides quick access to psychiatric phone consultation for primary care providers and facilitates referrals for mental health services in the community. Many pediatricians across the country have been able to provide additional mental health care to their own patients through the support of a CPAP consultation program in their state, instead of or while awaiting referral to mental health services in the community.

It takes a village

Pediatricians can improve youth mental health in America in many ways: within practices, communities, specialties, health systems, and states or in the national dialogue. It will require all sectors of society working together toward a shared vision to support mental health, address complex root causes, and provide access to high-quality, consistent, sustainable care. As a trusted voice for families, communities, and health systems, pediatricians have a unique opportunity to be the catalyst for real change. Each one of us will need to take a step out of our own comfort zones to make this happen. We have the tools and must play our part.

References

1. AAP-AACAP -CHA declaration of a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health. American Academy of Pediatrics. Updated October 19, 2021. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/advocacy/child-and-adolescent-healthy-mental-development/aap-aacap-cha-declaration-of-a-national-emergency-in-child-and-adolescent-mental-health/

2. US Department of Health and Human Services. Protecting youth mental health: the U.S. surgeon general's advisory. 2021. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/surgeon-general-youth-mental-health-advisory.pdf

3. Steiner RJ, Sheremenko G, Lesesne C, Dittus PJ, Sieving RE, Ethier KA. Adolescent connectedness and adult health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2019;144(1). doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3766

4. Osgood, K., Sheldon-Dean, H., & Kimball, H. 2021 Children’s Mental Health Report: What we know about the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on children’s mental health –– and what we don’t know. Child Mind Institute. 2021. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://childmind.org/awareness-campaigns/childrens-mental-health-report/2021-childrens-mental-health-report/

5. Data resource center for child and adolescent health. The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. https://www.childhealthdata.org/browse/survey/results?q=8556&r=1&g=908.

6. Curtin SC. State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2018. NVSS. 2020;69:(11). Accessed February 2, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/93667

7. Curtin S, Hedegaard H, Ahmad F. Provisional numbers and rates of suicide by month and demographic characteristics: United States, 2020. NVSS. 2021;(16). Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/VSRR016.pdf

8. Leeb RT. Mental health–related emergency department visits among children aged 18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic — United States, January 1–October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675-1680. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3

9. Addressing Mental Health Concerns in Pediatrics: A Practical Resource Toolkit for Clinicians, 2nd edition. American Academy of Pediatrics; 2021.

10. The Reach Institute. Accessed February 7, 2022. https://www.thereachinstitute.org/

11. Circle of Security International. https://www.circleofsecurityinternational.com/circle-of-security-model/what-is-the-circle-of-security/

12. American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://downloads.aap.org/AAP/PDF/periodicity_schedule.pdf

13. Weitzman C, Wegner L. Promoting optimal development: screening for behavioral and emotional problems. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):384-395. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-3716

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Screening tool finder. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/screening-technical-assistance-and-resource-center/screening-tool-finder/?page=1

15. Healthy Steps. What we do. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.healthysteps.org/what-we-do/our-model/

16. American Medical Association. Behavioral health integration compendium. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/bhi-compendium.pdf

17. American Psychiatric Association. Learn about the collaborative care model. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care/learn

18. Roadmap to resilience, emotional, and mental health. The American Board of Pediatrics. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.abp.org/foundation/roadmap

19. Entrustable professional activities for general pediatrics. The American Board of Pediatrics. Accessed February 2, 2022. https://www.abp.org/content/entrustable-professional-activities-general-pediatrics