Infant Sleep: Answers to Common Questions From Parents

As a result of misinformation or a lack of knowledge about healthy infant sleep, many parents and their babies suffer needlessly-and no one gets enough sleep. A baby’s sleepwake cycles are likely to appear unpredictable to new parents. This, coupled with conflicting advice about infant sleep, can lead to parents simply letting the baby sleep “whenever.” In such a situation, the baby often ends up with chronically insufficient sleep, which, if left unchecked, can spiral into persistent night awakenings and bedtime resistance.

As a result of misinformation or a lack of knowledge about healthy infant sleep, many parents and their babies suffer needlessly-and no one gets enough sleep. A baby’s sleepwake cycles are likely to appear unpredictable to new parents. This, coupled with conflicting advice about infant sleep, can lead to parents simply letting the baby sleep “whenever.” In such a situation, the baby often ends up with chronically insufficient sleep, which, if left unchecked, can spiral into persistent night awakenings and bedtime resistance.

A good understanding of the unique nature of infant sleep-wake cycles can help pediatricians prevent such problems by providing parents with more effective advice regarding their baby’s sleep. Here I provide a brief overview of infant sleep, with a special emphasis on the importance of sufficient sleep. I then present specific information you can draw on when advising your patients’ parents about common sleep-related concerns.

WHY SUFFICIENT SLEEP IN INFANCY IS SO IMPORTANT

Sufficient sleep is vital for humans of all ages. Sleep loss in adults has been shown to lead to, among other things, apathy, attention problems, irritability, increased errors, increased illness, increased aggressive behavior, impulse control problems, difficulty with problem solving,1 and even difficulty in making moral decisions.2 Parents of newborns are likely to have experienced several of these sequelae firsthand and are acutely aware of the short-term consequences of inadequate sleep. However, adults are not unique in being adversely affected by a lack of sleep.

Most, if not all, of the above consequences have a parallel in pediatric populations. In children, there are established associations between short (or irregular) sleep and poor school performance, school absences, weight gain and obesity, mood changes, alterations in ability to manage emotions or deal with failure, impulsivity, and attention difficulties.1 Prospective studies show that sleep problems in infancy or early childhood increase the risk of later development of depression and anxiety,3 alcohol and substance abuse,4 behavior problems,5 attention disorders,6 sleep disorders,1 and obesity.7

Sleep’s role in the development of infants’ brains. The developing brain may be particularly vulnerable to sleep loss. In altricial species such as humans, in which the young are born with visual and other systems not fully developed, sleep plays a unique and crucial role in learning and development. For example, there is evidence that sleep enhances plasticity in the developing visual cortex.8 Consequently, the young of such species have a far greater sleep need than do the adults. Moreover, the brain of an adult human can make up for lost sleep to a certain extent via known neural mechanisms. However, these neural mechanisms only emerge after the early years of life and are not functional in babies.9 Thus, infants cannot compensate for a loss of the sleep they need for optimal neurodevelopment.

Yet babies are sleeping less than ever. A 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America poll showed that, on average, infants are sleeping 12.7 hours per 24-hour period. This is substantially less than the 14 to 15 hours per day sleep experts recommend for 3- to 11-month-olds. Epidemiological data show similar trends, with babies and toddlers in particular sleeping less than they did 4 or 5 decades ago.10 In part, this is a consequence of bedtimes being moved later in the evening hours, while morning awakening times have remained largely unchanged.

Thus, it is important that pediatricians empower parents to protect their baby’s sleep time much as they would any health-promoting strategy and to identify and respond to their baby’s signs of sleepiness with opportunities for sleep and rest.

THE NATURE OF INFANT SLEEP

Biological clocks and clock-dependent alerting. Parents may well ask you: If it’s true that my baby needs so much sleep, then why isn’t he falling asleep all the time? Or: If my baby is as sleep-deprived as you say she is, then how come she has such a hard time falling asleep and staying asleep?

The answer to such questions is that in infants as well as in adults, the drive to sleep is determined not just by the sleep debt (need for sleep) that accumulates throughout the time they are awake but also by a biological clock that makes humans less likely to fall asleep at certain times of the day than at others. In certain phases of these sleep-wake cycles, it is difficult to initiate or maintain sleep; whereas in other phases, this is more readily accomplished. For example, workers of the graveyard shift know how difficult it can be to sleep well during the day, no matter how sleep-deprived they are.

During an active or wake phase of the sleep-wake cycle, the drive to sleep is opposed and the drive to be awake emerges. During an inactive or rest/sleep phase, the drive to promote alertness subsides and can no longer oppose sleep, thereby allowing sleep to occur.

In adults, this sleep-wake cycle is a circadian rhythm that promotes alertness essentially during the sunlight hours-a phenomenon known as clock-dependent alerting.

There is evidence of roughly 24-hour rhythms in infants as well. The fact that many newborns have a fussy time of day despite a chaotic sleep schedule suggests that even at this early age an internal 24-hour clock is already functioning in some capacity. In addition, although an infant can take weeks to entrain to the local light-dark environment, most infants past the newborn stage are exquisitely sensitive to the dawn’s early light (to the chagrin of some parents). This is likely to remain consistent regardless of when they were put to bed the night before.

Special alertness rhythms in infants. In addition to a nascent 24-hour rhythm, infants appear to have a shorter alertness rhythm in which a cycle is completed every 90 minutes. This 90-minute rhythm is likely an extension of the same rhythm that governs rapid eye movement (REM)/non–rapid eye movement (non-REM) cycles during sleep in all humans.

This 90-minute rhythm in particular seems tightly connected to sleepiness and alertness across the first year or so of life. This means that about 90 minutes after an infant awakens, alertness will have reached the lowest point in the cycle. This drop in alertness does not produce sleep, it merely makes it possible for sleep to occur. The brief window of sleepiness is not open long-typically for minutes only. If the infant is not given an opportunity to engage sleep during this window, his alertness clock will continue to run, proceeding into the next active and alert phase of the cycle, and he will remain awake until the next nadir-about 90 minutes later. Gradually across the first years of life, babies become better able to stay awake for whole-integer multiples of 90 minutes, ie, 3 hours, 4.5 hours, and so forth.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS OF INFANT SLEEP CYCLES

Encourage parents to bring the same dedication to good sleep habits that they bring to inculcating healthy eating habits in their children. In fact, it has been suggested that sleep is like food for an infant’s brain. Just as infants need frequent feedings, they need frequent naps.

Assessing adequacy of current sleep habits. First, help parents assess whether their baby is currently getting enough sleep. The following descriptions, when applicable, can serve as hints that an infant may not be well rested:

- The baby can only sleep while riding in a car or in a stroller or mechanical swing.

- The baby always falls asleep when in the car or stroller-or motion never fails to trigger sleep in him.

- The baby only catnaps for short periods (about 20 to 30 minutes at a stretch).

- The baby sleeps less than 3 hours total during the day.

- The baby can only fall asleep while being nursed or fed.

- There is no kind of regular nap schedule from day to day (some kind of morning nap, afternoon nap, and possibly evening nap).

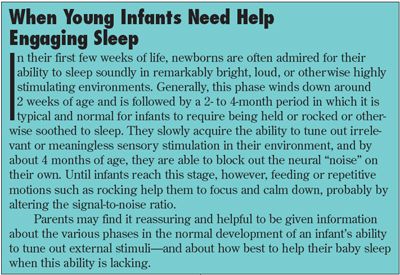

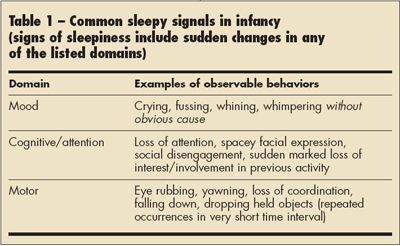

Learning to identify “sleepy signals.” To ensure that their baby gets the naps he needs, encourage parents to look for signs of sleepiness in their child and then respond to these expeditiously (Box). See Table 1 for a list of common sleepy signals in infancy. Unless parents are watching for these signs, it is very easy for them to overlook the baby’s sleep need, and as a result, for their child’s brain to miss out on a “feeding.”

Remind them that a good deal of fussiness in babies is a result of sleepiness. This particular signal is often misinterpreted; however, once parents are made aware that sleepiness is a possible cause of fussiness or clinginess and they learn to respond to fussiness appropriately, their baby’s sleep cycles can quickly become much easier to manage.

Advise parents also to keep in mind that babies’ sleepiness responses can be idiosyncratic. Thus, knowing about the 90-minute rhythm and attempting to follow it in their child will help them identify his unique sleepy signals.

Getting to bed on time. Stress to parents the importance of an appropriate and fairly regular bedtime for their child. Be sure they understand that because infants are so sensitive to the alerting effect of early morning light, most (although not all) are unable to “sleep in” if kept up later at night.

COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT INFANT SLEEP

Around what age will my baby no longer need nighttime feedings?

1Here, many parents seek a magic number-a specific age or weight at which the baby will no longer awaken at night. What many parents do not realize is that feeding the baby at each night waking is the best way to ensure that night awakenings will continue to occur. In part, night awakenings are the result of circadian clock entrainment of digestive responses, such as the production of liver enzymes. However, other factors are at play as well. Some of these are counterintuitive, and understanding them may be helpful to parents. Here are some of the important but perhaps counterintuitive points you can convey to parents:

•All babies awaken in the night. In fact, all adults do too-they just tend not to recollect it. (Adults have short-term awakenings roughly every 90 minutes, generally corresponding to a period of REM sleep, after which they usually fall right back to sleep.) Babies characterized as poor sleepers have been shown to awaken with the same frequency as good sleepers: the difference is that the so-called poor sleepers cry when they awaken.

•Babies awaken and cry for reasons other than hunger. Sometimes what they cry out for is assistance in getting back to sleep. Although it may seem counterintuitive, one of the more common causes of crying on awakening in the night is insufficient daytime sleep. After an REM period is completed, a well-rested baby will awaken briefly and then quickly resume sleeping, whereas an underslept baby will be more likely to come to a state of full wakefulness and then cry out for assistance in going back to sleep.

•Rare is the baby who refuses food in the middle of the night. Parents can misinterpret a baby’s vigorous enthusiasm for the breast or the bottle as an indicator of nutritional need, and this belief may make them unwilling to withdraw-or to gradually phase out-feedings at night. However, seeing whether a baby will eat when he awakens crying is not the way to determine whether a feeding is still needed. A study comparing a group of 8-week-olds who were not fed between midnight and 5 am (but who were instead soothed and rocked and comforted if they awoke) showed earlier achievement of “sleeping through the night” than did a similar group of infants who were fed “on demand” during those same hours.11 Interestingly, caloric intake did not differ between groups, suggesting that many babies who are not fed at night are able to make up the “lost” calories elsewhere in the day.

Certainly, throughout the newborn period, most infants are probably hungry when they awaken at night. However, after that, infants who are gaining weight well and are otherwise healthy may no longer need their nighttime feedings. You can encourage the parents of such infants to try, with your supervision, to reduce these feedings and instead to comfort and soothe their baby when he awakens and cries. You might also suggest that in certain cases, parents consider the possibility that their baby is underslept and that increasing daytime sleep might promote better nighttime sleep.

What age is best for trying to get babies to sleep on their own?

2As with many developmental milestones, there is no single age at which self-soothing (also known as getting an infant to fall asleep on his own, without parental assistance) is uniformly achieved. Also, to date there have been no comprehensive studies on its emergence. A general rule of thumb for most normally developing infants is that they will learn to self-soothe around the 6-month mark, or somewhere between 5 and 7 months. Certainly, some infants are ready earlier and others later. It is never too late for a child to make this transition; however, it is more difficult for both parents and children at later ages.

Stress to parents that this 5- to 7-month window applies to infants who are sleeping adequately during the day and are not waking frequently at night. It does not apply to an infant who you or the parents suspect is not getting enough sleep. Poorly rested babies are needier, fussier, or clingier, and it is possible that attempts to teach them self-soothing via any method will backfire. To maximize their chances of success, encourage the parents of insufficiently rested infants to help their baby establish a reasonably predictable nap and bedtime schedule and to make sure he is well rested before they try to get him to sleep on his own. Parents can work on daytime naps by following their baby’s sleepiness signs. Also, knowing when the infant is likely to be sleepy is a key component to the success of any self-soothing strategy.

How do I get my baby to fall asleep on his own and stay asleep?

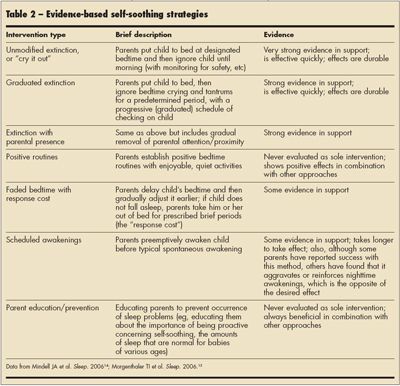

3There are many methods for training a child to self-soothe. The approach to teaching self-soothing that has been attributed to Ferber12-also known as the extinction or “cry it out” method-can be highly effective, works quickly, and seems to have more “staying power” than other approaches. There is no hard evidence that this approach has detrimental effects, either short or long term. Other approaches to enabling self-soothing may be less stressful for the parents, but these tend to take longer to take effect. Also, in my experience, infants with whom other approaches are used are more vulnerable to backsliding with changes in caregiver or sleeping environment (eg, as a result of travel), and families may find that they need to revisit the training process. For tips on when to initiate the extinction approach, see the answer to question 2, above.

The evidence on the results associated with several different self-soothing strategies is summarized in Table 2.

At what age should I try to eliminate my baby’s morning nap-and what is the best way to do this?

4The morning nap will drop out on its own somewhere between 12 and 18 months of age. Because of the risk of sleep loss due to the elimination of a needed nap, I recommend that parents not be encouraged to initiate eliminating the morning nap. Also, alert parents that the entire process of adjusting to the “missing” nap, which will reset other nap and sleep times, does not happen overnight and may take several weeks to fully sort itself out. The evening nap is generally the first nap to disappear but may be present even up to 9 or 12 months of age. The afternoon nap can persist in children as old as 6 years. Some parents regard outgrowing a nap as an indicator of high intelligence. There is no evidence for this association. Children should be allowed to sleep as much as is needed for them to be happy, healthy, and alert.

My baby was sleeping through the night but then started waking up again? What should I do?

5Parents may want to attribute the awakenings to teething or other developmental milestones, but there is little evidence for this. Make parents aware that although the achievement of sleeping through the night is welcome, it is never permanent. Developmental milestones, such as crawling or standing, cause ripples in a child’s sleep habits. In addition, the 90-minute alertness rhythm undergoes changes in toddlerhood. However, if an infant has been taught to self-soothe, and if the parents promote healthy sleep habits and understand their baby’s sleepy signals, they should be able to adapt to these changes. Often-although not always-once an infant has learned to fall asleep on his own, this skill generalizes fairly quickly to middle-of-the-night awakenings. Note that feeding, rocking, or bringing the infant into the parents’ bed reinforces full-fledged awakenings.

In some cases, the cause of the nighttime awakenings is that the infant is not getting adequate sleep during the day, or that he has skipped (or rescheduled-usually delayed) a nap, which can have a sort of “jet lag” effect on an infant’s sleep. Even when another cause for the awakenings can be identified, nighttime awakenings are more likely to reappear when the infant’s total sleep time is not sufficient. Thus, advise parents to make sure their child is getting enough daytime sleep.

In cases in which an infant is sleeping well at night but is awakening too early in the morning, parents often assume that keeping him up later at night will delay the time of his morning awakening the next day. However, more often than not the opposite happens and the infant awakens even earlier. Sometimes the solution is for the infant to get more sleep. However, remind parents that it is natural for infants and toddlers to be early risers.

We really like having our baby in bed with us. What is your opinion of cosleeping?

6The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) advises against cosleeping under most circumstances because of reports of deaths of cosleeping infants resulting from suffocation- whether caused by an overlying adult (particularly an adult in a depressed state of consciousness), soft sleep surfaces, entrapment, or the greater likelihood that the infant would roll into the prone position.13

The AAP does not categorically condemn the practice; however, it stresses that a number of criteria must be met for cosleeping to be a reasonable sleeping arrangement for an infant. These include the following:

- The infant must be put to sleep in the nonprone position.

- Soft surfaces (eg, pillows, quilts, porous mattresses) and loose covers must be avoided.

- Entrapment risks should be eliminated by moving the bed away from the wall and other furniture and by not using a bed whose design itself presents an entrapment risk.

- Parents who cosleep should not smoke or use substances, such as alcohol, that may impair arousal.

- No adults other than the parents and no other children should share the bed with the infant.13

There are 2 other concerns that I advise parents to keep in mind when considering cosleeping. One is that a child who cosleeps is likely to become dependent on the presence of the parent in order to sleep and will not be able to sleep on his own. Only very rarely have I seen cosleeping families avoid this pitfall. Another concern is that a cosleeping infant may have insufficient opportunity for sleep.

Thus, in addition to the recommendations of the AAP, I would add that it is important for any parents who choose to cosleep with their baby to make sure that the infant’s sleep needs are being met (eg, by ensuring opportunities for adequate daytime naps and by taking care that sleep onset for their baby is not dictated by their own bedtime). I also would advise cosleeping parents to allow their child at least occasional opportunities to “self-soothe” and to establish a target age by which they will try to have the child sleeping on his own. Even with a time frame, however, it is the rare family that completely averts difficulties with this challenging transition later on.

An alternative to cosleeping that can provide some of the advantages-such as convenient breastfeeding and parent contact-but that eliminates the potential hazards and other associated problems, is for parents to place their infant’s crib near their bed.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Mindell JA, Owens JA. Sleep problems in pediatricpractice: clinical issues for the pediatric nursepractitioner.

J Pediatr Health Care.

2003;17:324-331.

2.

Killgore WD, Killgore DB, Day LM, et al. Theeffects of 53 hours of sleep deprivation on moraljudgment.

Sleep.

2007;30:345-352.

3.

Gregory AM, Caspi A, Eley TC, et al. Prospectivelongitudinal associations between persistent sleepproblems in childhood and anxiety and depressiondisorders in adulthood.

J Abnorm Child Psychol.

2005;33:157-163.

4.

Wong MM, Brower KJ, Fitzgerald HE, ZuckerRA. Sleep problems in early childhood and earlyonset of alcohol and other drug use in adolescence.

Alcohol Clin Exp Res.

2004;28:578-587.

5.

Gregory AM, O’Connor TG. Sleep problems inchildhood: a longitudinal study of developmentalchange and association with behavioral problems.

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

2002;41:964-971.

6.

Wolke D, Rizzo, Woods S. Persistent infant cryingand hyperactivity problems in middle childhood.

Pediatrics.

2002;109:1054-1060.

7.

Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, et al. Shortsleep duration in infancy and risk of childhood overweight.

Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.

2008;162:305-311.

8.

Frank MG, Issa NP, Stryker MP. Sleep enhancesplasticity in the developing visual cortex.

Neuron.

2001;30:275-287.

9.

Jenni OG, Borbély AA, Achermann P. Developmentof the nocturnal sleep electroencephalogramin human infants.

Am J Physiol Regul Integr CompPhysiol.

2004;286:R528-R538.

10.

Iglowstein I, Jenni OG, Molinari L, Largo RH.Sleep duration from infancy to adolescence: referencevalues and generational trends.

Pediatrics.

2003;111:302-307.

11.

Minde K, Popiel K, Leos N, et al. The evaluationand treatment of sleep disturbances in youngchildren.

J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

1993;34:521-533.

12.

Ferber R.

Solve Your Child’s Sleep Problems.

New York: Fireside Book; 2006.

13.

American Academy of Pediatrics Task Forceon Infant Sleep Position and Sudden Infant DeathSyndrome. Changing concepts of sudden infantdeath syndrome: implications for infant sleeping environmentand sleep position.

Pediatrics

. 2000;105:650-656.

http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;105/3/650

. Revised November1, 2005. Accessed January 15, 2009.

14.

Mindell JA, Kuhn B, Lewin DS, et al; AmericanAcademy of Sleep Medicine. Behavioral treatmentof bedtime problems and night wakings in infantsand young children [published correction appearsin Sleep. 2006;29:1380].

Sleep.

2006;29:1263-1276.

15.

Morgenthaler TI, Owens J, Alessi C, et al;American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practiceparameters for behavioral treatment of bedtimeproblems and night wakings in infants and youngchildren.

Sleep.

2006;29:1277-1281.