Is it an endocrine disorder or a "non-disease"?

Children referred for evaluation of an endocrine disorder often turn out to have findings that merely mimic the suspected disease. Early identification of these nondiseases can save patients and parents a lot of unnecessary testing and worry. First of two parts.

Is it an endocrine disorder or a "nondisease"?

By Michael S. Kappy, MD, PhD

Children referred for evaluation of an endocrine disorder often turn out to have findings that merely mimic the suspected disease. Early identification of these "nondiseases" can save patients and parents a lot of unnecessary testing and worry. First of two parts.

Many children whose initial appearance suggests a specific endocrine disorder are referred to subspecialists, where diagnostic evaluation often fails to substantiate the presumed diagnosis. For example, most children referred for evaluation for Cushing syndrome on the basis of round ("moon") facies, obesity, striae, and a "buffalo hump" are found instead to have exogenous obesity. The similarity of children with these conditions to one another, however, suggests a syndrome, which can be described as pseudo-Cushing or non-Cushing syndrome. Such children do require treatment, but for obesity, not Cushing syndrome. Early recognition of non-Cushing syndrome and other relatively common nondiseases by the primary care physician or pediatric endocrinologist helps to avoid unnecessary, costly, and stressful laborato ry and radiologic testing.

A nondisease exists when a constellation of physical and laboratory findings suggests a specific disease or syndrome that is not present. One of the first reports of nondisease was published by Meador in 1965.1 He described 15 of his patients and those from another group as having "non-Cushing disease."2 This review describes several such examples involving the endocrine system in children as well as guidelines and criteria for identifying nondisease.

In most cases, nondisease can be identified by taking a thorough history, performing a complete physical examination, calculating a child's growth rate, and, sometimes, assessing skeletal maturation using an X-ray of the left hand and wrist. Some children, such as those suspected of having parathyroid or thyroid disease, may require laboratory evaluation. Any normal values for tests or measurements not provided in the text or tables of this review can be found in the 15th edition of the Harriet Lane Handbook.3 This article explains how to distinguish children with conditions that mimic adrenal, carbohydrate, and gonadal diseases from those with true disease.

Adrenal nondisease

Nondiseases that mimic adrenal conditions include non-Cushing syndrome, non-Addison disease, and noncongenital adrenal hyperplasia (non-CAH).

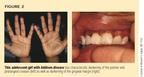

Non-Cushing syndrome is one of the most common examples of nondisease in children. Typically, these children are obese with a round face, a prominent fat pad at the base of the neck, striae, and, occasionally, some hirsutism (Figure 1). They may also have above normal blood pressure readings, especially if a standard pediatric blood pressure cuff is used for assessment. The criteria used to distinguish children with non-Cushing syndrome from those with true Cushing syndrome are height, growth velocity, fat distribution, skeletal maturation (bone age), and the presence or absence of acanthosis nigricans (Table 1).

Table 1

Criteria for distinguishing non-Cushing from Cushing syndrome

The majority of children with non-Cushing syndrome are tall, growing normally (or even a bit faster than normal for age), and have a bone age that is as advanced as their height for age. In addition, fat distribution is generalized. Apparent hypertension may be an artifact of using a blood pressure cuff that is too small for the diameter of the child's arm, and readings should be rechecked using an appropriately sized cuff. Excessive facial hair may reflect familial factors or the effect of increased circulating insulin concentrations on adrenal or ovarian androgen production, which is common in these children. Acanthosis nigricans, seen in the intertriginous areas of obese children, is another manifestation of hyperinsulinism and insulin resistance and is not usually seen in children with Cushing syndrome.

In contrast to obese children, children with Cushing syndrome are usually short, growing poorly, and have delayed skeletal maturation, all of which reflect the catabolic effects of glucocorticoid excess. Fat distribution in older children tends to be central or centripetal because of wasting of the limbs--another manifestation of the catabolic effect of glucocorticoids on muscle and bone. True hypertension may exist as a result of the sodium-retaining properties of glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids. Hirsutism may be present, reflecting excessive adrenal androgen production.

If the physical examination fails to distinguish clearly between Cushing and non-Cushing syndrome, an initial laboratory evaluation should consist of measuring serum electrolytes, glycosylated hemoglobin concentration, and 24-hour urinary free cortisol secretion. Random plasma cortisol or AM/PM cortisol concentrations may not differentiate the two conditions. The child with true Cushing syndrome will have a mildly elevated serum sodium, a decreased serum potassium, and an elevated glycosylated hemoglobin concentration indicative of chronic hyperglycemia. In extreme cases, a low-dose dexamethasone test followed by a high-dose test, may be necessary.4 Children with non-Cushing syndrome are also often referred to rule out acquired hypothyroidism, but their tall stature, relatively rapid growth, and normal-to-advanced skeletal maturation make this diagnosis unlikely.

Non-Addison disease. The patient usually referred for suspected Addison disease is an adolescent girl with pallor, fatigue, weight loss, loss of appetite, oligomenorrhea, borderline hypotension, and, occasionally, episodic vomiting. While this constellation of findings is also common to patients with anorexia nervosa, anorexic patients typically have abnormal eating attitude profiles on testing with the Eating Attitude Test (EAT), while patients with Addison disease do not.5 In addition, because of the excessive secretion of the parent molecule of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in patients with Addison disease, their physical examination usually reveals darkly pigmented palmar and solar creases, areolae, thin, dark lines at the gingival margin (Figure 2), and a generalized bronzing of the skin or freckling without a tan line, especially noticeable in the winter months.

Patients with anorexia nervosa should not automatically be considered to have non-Addison disease. True Addison disease has been diagnosed in such patients, and the consequences of incorrectly diagnosing Addison disease or anorexia nervosa can be severe.6

Serum electrolyte and glucose concentrations may reveal the pattern seen with Addison disease (that is, adrenal insufficiency), which includes low sodium, bicarbonate, and glucose with elevated potassium and chloride. These values may be normal in either Addison disease or anorexia nervosa, however. In that case, measuring plasma renin activity and ACTH concentration is helpful. Both are elevated in patients with Addison disease and normal in those with anorexia. The measurement of antibodies against 21-hydroxylase enzyme is also useful in diagnosing Addison disease.7

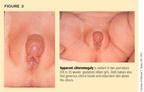

Noncongenital adrenal hyperplasia (apparent clitoromegaly in premature newborn females). Because envelopment of the clitoris by the labia majora begins at approximately 28 weeks gestation, premature newborn females have a more visible or prominent clitoris than those who are born closer to term. Occasionally, this apparent clitoromegaly leads to an evaluation for a virilizing form of congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), most commonly the type caused by 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Figure 3 shows two such infants. A careful examination of the external genitalia can obviate the need for such an evaluation, which may be difficult in this age group and may necessitate laboratory, radiologic, and chromosomal testing.

Precise measurement of the corpora of the clitoris is necessary since some of the observed clitoromegaly may result from redundant skin. Riley and Rosenbloom reported normal clitoral breadth as being less than 5 mm and showing no significant change with gestational age.8 Yokoya and colleagues and Phillip and associates found normal clitoral lengths of less than 10 mm in term newborns with no relation to gestational age and no significant increase over the first year of life.9,10 In 44 girls with virilizing CAH between 2 months and 13 years of age, on the other hand, Maruyama and colleagues estimated a mean clitoral length of 18 mm at birth and a clitoral growth rate of 1.8 mm/year.11

Female infants with virilizing forms of CAH almost always have additional signs of virilization, such as rugation ("scrotalization") of the labia majora, and some degree of posterior fusion of the labia minora (Figure 4), although the latter varies considerably. The degree of fusion can be measured by comparing the ratio of the anus-to-fourchette distance (AF) to the anus-to-base of clitoris distance (AC). The resultant anogenital ratio (AF/AC) is less than 0.5 in normal female newborns and is independent of gestational age.8,12

While all premature female infants have some degree of apparent clitoromegaly, only one in about 5,000 has CAH. Thus, a comprehensive evaluation for CAH should be reserved for those infants who exhibit true clitoromegaly usually with other signs of virilization of the external genitalia. The vast majority of prematurely-born females have non-CAH.

Carbohydrate nondisease

Nonhypoglycemia in adults was described as an epidemic by Yager and Young in 1974.13 The patients we see in referral are usually teenagers in good health who develop symptoms compatible with hypoglycemia two to five hours after meals. Symptoms may include pallor, sweating, tachycardia, weakness, dizziness, and occasional syncope without injury at school or at home. The symptoms generally do not occur after relatively prolonged fasting (as upon awakening) or with any consistent relation to mealtimes. Furthermore, they are not related to vigorous physical activity and subside when the patient eats.

A family history may reveal a similar picture, past or present, in one or both parents. The physical examination does not show evidence of undernutrition, hypopituitarism, Addison disease, hyperthyroidism, or insulin excess. Moreover, the nature and timing of the symptoms, as well as the normal physical examination, generally rule out pathologic causes of hypoglycemia. If an initial laboratory evaluation is undertaken, the fasting blood glucose concentration is normal, and if the patient is given test strips to monitor blood glucose concentrations visually at home, these too are almost always normal.

Oral glucose tolerance tests are rarely necessary, but if they are done, the patient's behavior must be observed during the entire test in order to document an association between the symptoms and the patient's ambient blood glucose concentration. As a rule, patients remain asymptomatic during the test, even if an occasional low blood glucose concentration (50 mg/dL or 2.8 mmol/L, for example) is seen. Occasionally, the patient will become symptomatic, but at times when the blood glucose concentration is clearly normal.14 The symptoms of nonhypoglycemia are generally manifestations of an adrenergic (adrenaline) or stress response, not necessarily hypoglycemia.15

In most cases, the adolescent with nonhypoglycemia and his or her family can be reassured that no pathology is present. Since the symptoms may reflect underlying anxieties regarding the patient's home or school environment, a psychologic interview followed by appropriate counseling may be necessary to alleviate the problem and should be suggested. Occasionally, empiric treatment with frequent, small feedings produces a good outcome. This result may be a placebo effect, however, and may reinforce the notion that suspected but undocumented hypoglycemia is causing the patient's problem.

Gonadal nondisease

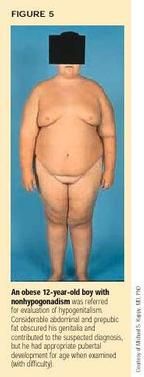

Gonadal nondiseases include nonhypogonadism in obese early adolescent boys and several forms of nonpuberty.

Nonhypogonadism in obese early adolescent boys. Since most boys begin to show testicular and penile enlargement by the time they are 12 years old, failure to do so may cause concern. In a boy of normal body weight, late development may simply be a constitutional delay of puberty, occasionally seen in one or both parents. If the boy is significantly overweight, his apparent failure to progress into puberty may reflect a difficulty in estimating the size of the penis. Pubic hair in such a child is likely to result from adrenal androgen production (adrenarche) rather than testicular function.

The physician should attempt, often with the help of a second examiner, to fully retract the abdominal fat and the prepubic fat pad, which, if extensive, may almost entirely obscure the penis from direct view (Figure 5). Obtaining a precise measurement of the traditional stretched penile length from the symphysis pubis to the tip of the glans may be impossible in such boys. An estimate of testicular volume and minimal penile length can usually be made, however, and the results compared to published normal values for age.3,16 As a rule, these measurements are normal, at least for skeletal maturation (bone age). Clearly, if a boy's measurements are less than normal but his skeletal maturation is delayed, constitutional delay of puberty is likely, and the diagnosis of hypogonadism should not be made until the boy has achieved an appropriate pubertal age skeletal maturation.

Nonpuberty: Infantile gynecomastia and premature thelarche. Breast development in girls younger than 6 years of age prompts consideration of central (gonadotropin-releasing hormone-dependent) precocious puberty,17,18 peripheral (autonomous) oversecretion of estrogen caused by an ovarian cyst or tumor, McCune Albright syndrome, or, rarely, an adrenal tumor or exogenous estrogen (oral or topical).

Breast development in girls from birth to 3 years of age does not usually progress to near-completion or completion (Tanner stage 4 or 5) or to other signs of puberty and is, therefore, more properly termed "gynecomastia" than "thelarche." Thelarche technically means "the beginning of breast development," implying continued progression. The term, premature thelarche is best reserved for girls close to 6 years of age in whom slow, continued breast development may actually be present without pathologic cause.

Girls from infancy to 3 years of age with enlargement of one or both breasts may show some increase in breast size over time but are not in early or precocious puberty. They do not, as a rule, grow at an excessive rate for age and do not have advanced skeletal maturation. Although some may have an isolated episode of withdrawal bleeding if breast enlargement is caused by a transient ovarian cyst, they do not have cyclic bleeding or periods. If they are evaluated for a suspected pathological condition, their plasma estradiol concentration is prepubertal, as is their response to GnRH (Table 2).19 Thus, they have "nonpuberty."

Table 2

Characteristics of gonadal nondisease (nonpuberty)

Girls: 47 yr

Boys: 49 yr

Breast enlargement (unilateral or bilateral)

No vaginal estrinization

Pubic hair

Apocrine body odor +/

Acne/axillary hair (rare)

Ultrasonography is usually unnecessary in the absence of rapid growth or skeletal maturation but may reveal multiple small cysts of the ovary in 50% of the girls. Such cysts are also present in 21% of girls of the same ages without breast development.20

Nonpuberty: Premature adrenarche. In girls aged 4 to 7 years or boys aged 4 to 9 years, the appearance of true pubic hair on the labia or base of the penis and occasionally on the mons leads to a suspicion of precocious puberty (or nonclassical, mild virilizing CAH). Typically, these children are tall, overweight, and growing at a rate that is slightly increased for age. Skeletal maturation may be advanced, but usually not by more than the age for which their height is the 50th percentile (Table 2). This pattern is characteristic of obese children since they commonly have early onset of adrenal androgen secretion, or premature adrenarche.21 A modestly advanced bone age is also common in these patients. In girls, the absence of breast development, as opposed to adipose tissue, suggests that precocious puberty is not present, and in boys, testicular volumes are prepubertal (less than 3 mL).

Laboratory studies should be performed if the diagnosis of premature adrenarche is in doubt after the above criteria are considered. A GnRH test will show a prepubertal rise in serum luteinizing hormone concentration in children with premature adrenarche.19 Measurements of adrenal androgen, specifically plasma dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) concentration, may not be prepubertal but are commensurate with the amount of pubic hair (Table 2). In nonclassical, or mild virilizing, CAH, the concentrations of adrenal androgens may be increased even for the extent of observed pubic hair but will be well below those seen in children with adrenal tumors. Thus, premature adrenarche is an example of nonpuberty or non-CAH.

Nonpuberty: Dark vellus hair on the mons of a female infant. Occasionally, female infants have dark, fine hair over the mons veneris. Often, such infants are from Mediterranean backgrounds (Hispanic, Italian, Greek, Levantine), and have relatively plentiful, dark body hair as a family trait. The hair is distinguishable from true pubic hair by its fine texture, and is termed "vellus." True pubic hair generally makes its first appearance on the vaginal labia (Tanner 2) before appearing on the mons (Tanner 3), whereas dark vellus hair is seldom present on the labia.22 Furthermore, these infants usually have normal growth rates and normal skeletal maturation. These findings and the absence of breast development suggest that they are not in puberty. Laboratory studies are generally not necessary but, if performed, show a prepubertal (nonpubertal) response to GnRH testing and normal adrenal androgen levels for age.19 Thus, these infants have non-CAH as well as nonpuberty.

A look ahead

Next month, the second part of this article will review syndromes that mimic parathyroid, pituitary, and thyroid diseases. It will also discuss non-Marfan syndrome.

REFERENCES

1. Meador CK: The art and science of nondisease. N Engl J Med 1965;272:92

2. Nugent CA, Warner HR, Dunn JT, et al: Probability theory in diagnosis of Cushing's syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol 1964;24:621

3. Sidberry GK, Iannone R (eds.): Harriet Lane Handbook, ed 15. St. Louis, Mosby, 2000

4. Migeon CJ, Donohoue P: Adrenal disorders, in Kappy MS, Blizzard RM, Migeon CJ (eds.): Wilkins The Diagnosis and Treatment of Endocrine Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, ed 4. Springfield, IL, Charles C Thomas, 1994, p 717

5. Miller MN, Verhegge R, Miller BE, et al: Assessment of risk of eating disorders among adolescents in Appalachia. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1999;38:437

6. Sigal E, Kappy MS: Unpublished data. 2000

7. Falorni A, Nikoshkov A, Laureti S, et al: High diagnostic accuracy for idiopathic Addison's disease with a sensitive radiobinding assay for autoantibodies against recombinant human 21-hydroxylase. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995;80:2752

8. Riley WJ, Rosenbloom AL: Clitoral size in infancy. J Pediatr 1980;96:918

9. Yokoya S, Kato K, Suwa S: Penile and clitoral size in premature and normal newborns. Clin Endocrinol 1983; 31:1215

10. Phillip M, De Boer C, Pilpel D, et al: Clitoral and penile sizes of full-term newborns in two different ethnic groups. J Ped Endocrinol Metab 1996;9:175

11. Maruyama T, Tsugaya M, Ito T, et al: A clinical study on virilization of external genitalia in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Jpn J Urol 1999;90:27

12. Callegari C, Everett S, Ross M, et al: Anogenital ratio: Measure of fetal virilization in premature and full-term newborn infants. J Pediatr 1987;111:240

13. Yager J, Young RT: Nonhypoglycemia is an epidemic condition. N Engl J Med 1974;291:907

14. Palardy J, Havrankova J, Lepage R, et al: Blood glucose measurements during symptomatic episodes in patients with suspected postprandial hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1421

15. Berlin I, Grimaldi A, Landault C, et al: Suspected postprandial hypoglycemia is associated with b-adrenergic hypersensitivity and emotional distress. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1994;79:1428

16. Kelch RP, Beitins IZ: Adolescent sexual development, in Kappy MS, Blizzard RM, Migeon CJ (eds.): Wilkins The Diagnosis and Treatment of Endocrine Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence, ed 4. Springfield, IL, Charles C Thomas, 1994, pp 193-234

17. Herman-Giddens ME, Slora EJ, Wasserman RC, et al: Secondary sexual characteristics and menses in young girls seen in office practice: A study from the Pediatric Research in Office Settings Network. Pediatrics 1997; 99:505

18. Kaplowitz PB, Oberfield SE: Reexamination of the age limit for defining when puberty is precocious in girls in the United States: Implications for evaluation and treatment. Pediatrics 1999;104:936

19. Kappy MS, Ganong CS: Advances in the treatment of precocious puberty. Adv Pediatr 1994;41:223

20. Freedman SM, Kreitzer PM, Elkowitz SS: Ovarian microcysts in girls with isolated premature thelarche. J Pediatr 1993;122:246

21. Remer T, Manz F: Role of nutritional status in the regulation of adrenarche. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:3936

22. Marshall WA, Tanner JM: Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child 1969;44:291

THE AUTHOR is Chief of Pediatric Endocrinology at the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center, The Children's Hospital, Denver, CO.

Michael Kappy. Is it an endocrine disorder or a "non-disease"?.

Contemporary Pediatrics

2000;10:83.

Having "the talk" with teen patients

June 17th 2022A visit with a pediatric clinician is an ideal time to ensure that a teenager knows the correct information, has the opportunity to make certain contraceptive choices, and instill the knowledge that the pediatric office is a safe place to come for help.