Mobile clinic to the rescue

Pediatrician Randal C. Christensen, MD, MPH, medical director of Crews’n Healthmobile, says he has the best job in the world. “I literally spend my clinical time taking care of homeless children and teens. I don’t have to ask for insurance cards or wait for them to come and see me. I go and see them,” he says.

Pediatrician Randal C. Christensen, MD, MPH, medical director of Crews’n Healthmobile, says he has the best job in the world. “I literally spend my clinical time taking care of homeless children and teens. I don’t have to ask for insurance cards or wait for them to come and see me. I go and see them,” he says.

Crews’n Healthmobile, part of Phoenix Children’s Hospital in Phoenix, Arizona, includes a freestanding clinic, 3 mobile medical units, and a staff of 31 healthcare providers and administrators. Crews’n provides holistic healthcare to Arizona’s homeless and at-risk youth and links kids with needed services, including job placement.

From a medical perspective, Christensen says delivering needed care to homeless patients allows him to practice medicine on his terms.

“I’m listening and making a diagnosis of pneumonia based on a physical exam, rather than being in an emergency [department] and ordering 3 sets of x-rays, a pulmonary analysis, full bloodwork,” Christensen says. “I’ve seen dislocated arms, legs, and fingers. I’ve seen new onset diabetes. People come in with common complaints that they would go to a pediatrician for-they just happen to come very, very late. The ear infection-it’s not just a little red and the eardrum doesn’t move very well. You look at it, and there’s pus coming out of it. I can’t tell you the number of cockroaches I’ve taken out of ears.”

According to Children’s Health Fund, which partners with organizations that have children’s mobile healthcare organizations including Crews’n Healthmobile, there are about 51 mobile health clinics in the United States.1 That represents clinics at about 25 sites, Christensen says.

About these patients

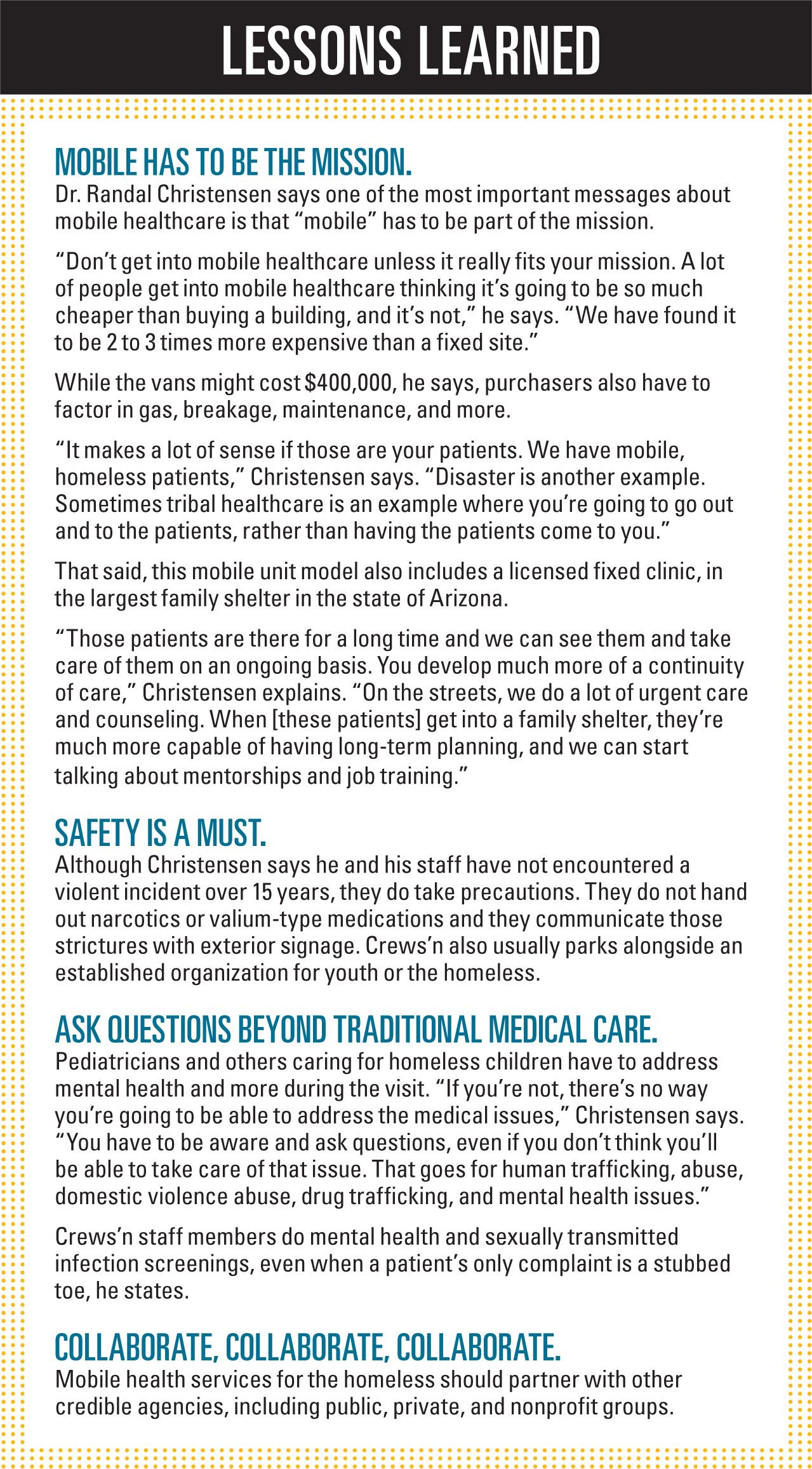

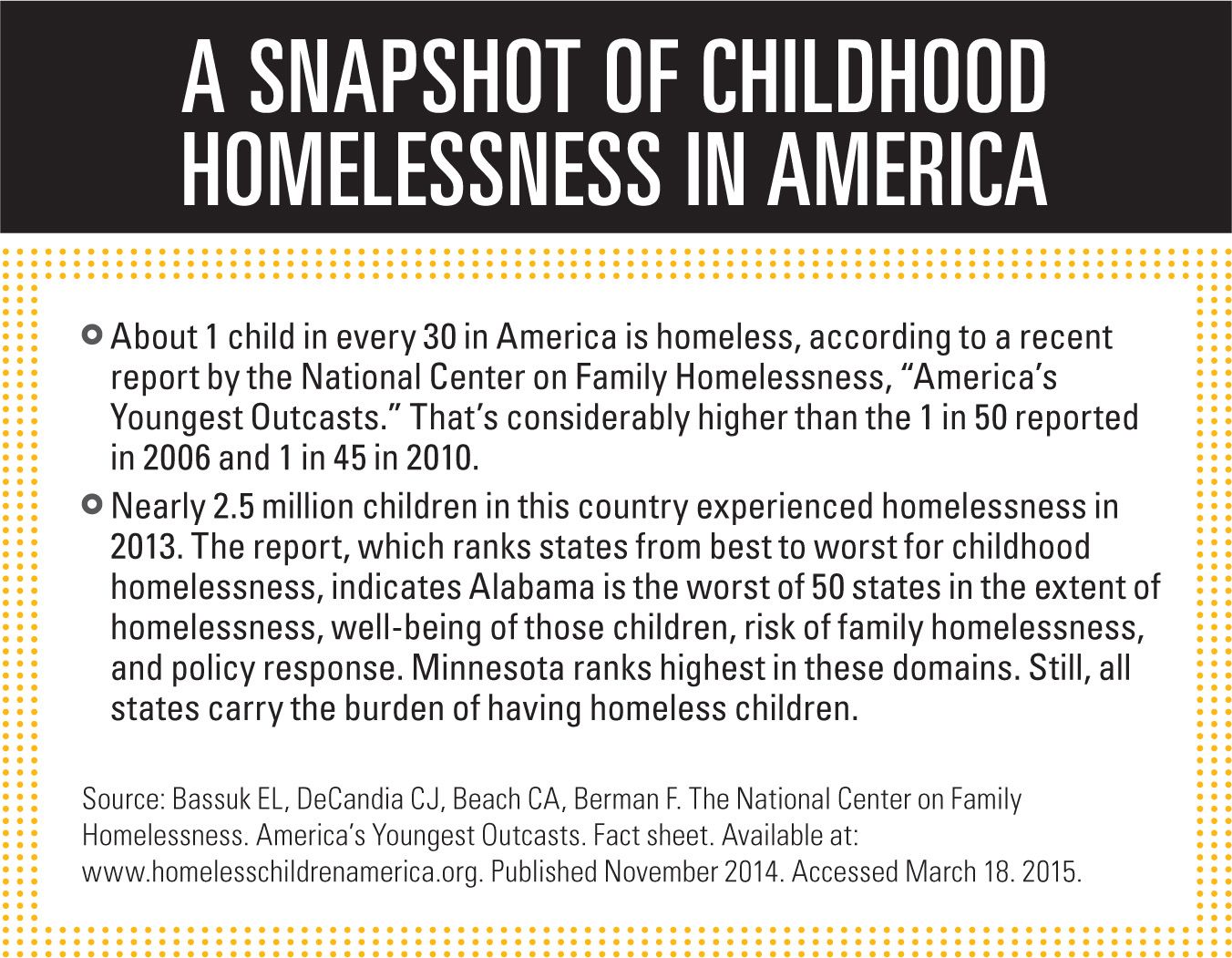

The National Alliance to End Homelessness, a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization focused on preventing and ending homelessness in America, released its report “The State of Homelessness in America 2014.” The recent document was the first of 4 such reports to include homeless youth as a subpopulation, suggesting these children comprise almost 8% of the homeless population.2

More: Is it prediabetes or TD2?

Main drivers of homelessness among US children include: America’s high poverty rate and lack of affordable housing; lingering economic challenges; racial disparities; and single parenting. Another driver is the impact of traumatic experiences, especially domestic violence, which precede and prolong homelessness among children and families.3

“Many homeless children struggle in school, missing days, repeating grades, and dropping out entirely. Up to 25% of homeless preschool children have mental health problems requiring clinical evaluation. This increases to 40% among homeless school-aged children. The impacts of homelessness on the children, especially young children, may lead to changes in brain architecture that can interfere with learning, emotional self-regulation, cognitive skills, and social relationships. The unrelenting stress experienced by the parents may contribute to residential instability, unemployment, ineffective parenting, and poor health,” according to America’s Youngest Outcasts.3

NEXT: How does Crewsn' fill a long-neglected niche?

Crews’n toward a solution

Crews’n Healthmobile launched its mobile health program in the fall of 2000, with 1 specially equipped van, a nurse practitioner, and Christensen. The pediatrician was not long out of his residency but had a history in healthcare for the homeless. While in medical school at Tufts University, he provided healthcare to the homeless in Boston’s Harvard Square. He continued similar work throughout his residency at Phoenix Children’s Hospital and afterward as a staff physician at a local school for homeless children.

Christensen's work at Crews’n started with a focus on traditional medical care and making sure the kids received needed medications. However, several years into the mobile service, Christensen realized that although he was helping to address acute medical issues, few, if any, of his patients were getting off the streets. “It was at that time that we began to think of this in a whole different manner,” he says.

Recommended: Linking poor families with fresh fruits and vegetables

Christensen conducted a few unpublished studies and found that although children would come to the mobile healthcare van for simple colds, flu, ear infections, asthma, skin infections, and the like, many also had been raped and brutalized. “They had tragic stories, and they were schizophrenic and suicidal. They were using drugs at 2 or 3 times what their counterparts were,” he says.

In an unpublished survey done to help with program evaluation, Crews’n staff noted serious mental health issues among patients in a 6-month period. Forty-four percent of patients surveyed answered yes to the statement “In the last 6 months, have you hurt yourself intentionally with the thought of killing yourself?” Eighty-two percent were substance abusers and 66% indicated they were depressed. “That’s when we started to believe in this whole medical home [concept],” he says.

Christensen’s survey corroborated longstanding medical literature on the poor prognosis of this cohort of at-risk adolescents. In a study published in the Journal of Adolescent Health in 1991, researchers found homeless/runaway youth were 6 times more likely to be at risk for HIV infection compared with youth who had homes. Homeless teenagers also were more likely to have dropped out of school, to be depressed and actively suicidal, to engage earlier in sexual intercourse, and to be sexually abused or engage in prostitution.4

Spokes of a wheel

Christensen explains that he and his staff view healthcare of homeless children as spokes of a wheel.

“The only way that you’re ever going to get that wheel to roll is if you have all the spokes in. Medical care is certainly one of those things, but safety, security, shelter and mentorship, dental health and mental health, and job training-all these other spokes of the wheel have to be in place,” he says. “Otherwise you’re never going to be able to change the cycle of homelessness.”

Developing partnerships

To add needed spokes, the Crews’n staff developed and continues to develop partnerships with a wide variety of organizations that can help Christiansen’s patients. These include state and government agencies, churches, schools, and more. The goal is to link with groups that can help children address other issues, from mental health, to breaking the cycle of abuse, to jobs skills and training.

“If they came to us and they were on the streets, we would connect them with an organization in town that was providing shelter. We have a mentorship program for those interested in nursing skills, and, lo and behold, we have 20-some people that are in some form of nursing school,” he says. “It has just sort of blossomed into this overarching philosophy where we really want to help them address those causes or challenges that keep them from getting off the streets.”

NEXT: What did they need to serve their patients?

Getting it on the ground

Crews’n Healthmobile has 3 38-foot vans, including the first. The second, purchased in 2008, was recently refurbished. The third-a state-of-the-art van, according to Christensen-was unveiled in December 2014.

Equipped with LED lights, the new van requires only a percentage of the battery load of the older models. That’s critical because the huge batteries required to run the older vans cost about $2000 a year to replace, Christensen explains. In addition, the van’s sophisticated refrigeration system features round-the-clock monitoring to let the staff know if optimal temperatures aren’t being maintained for vaccines and other medications. The system starts a generator, when needed, to keep the medications cool, and produces reports and logs for agencies.

Recommended: The diaper bank concept

The rooms inside the vans look much like those in a doctor’s office, according to Christensen, with exam rooms, a nursing area, and sometimes a staff kitchenette. Also, the vans have surfaces that allow for hospital-grade cleaning.

To keep the vans at 26,000 pounds or less (special drivers’ licenses are required with heavier vehicles), Christensen opted not to include x-ray equipment. Instead, Crews’n collaborates with facilities that offer x-rays, and with taxi cab companies as well in case children need rides to those places.

Where to go?

Mobile vans go to homeless children in closest proximity to the greatest need. To make the most of each stop, Crews’n vans try to go to places with the highest density of homeless youth, such as a nonprofit shelter or youth center. With the addition of the new van, Christensen says he will be able to send staff as far away as 50 miles from downtown Phoenix.

“[W]e’ve never had enough mobile units to be able to go farther out, so we had to maintain the team right around Phoenix Children’s or around the local city. Now, with this new capability, we’ll be able to go out farther and spend the entire day out there. Part of that is having another mobile unit; part is having more staffing,” he says.

On a typical day, a physician, nurse, and case manager will be on the van. Depending on the site, Christensen might also send a social worker, and sometimes residents and medical students join the staff.

Business is brisk

Crews’n staff sees about 1800 unique patients a year, amounting to approximately 4500 medical visits. Add another few thousand visits focused more on case management, and the staff handles some 7000 visits a year, Christensen says. That’s grown from about 500 medical visits in 2001.

Today’s total budget for the program is estimated at $2.2 million. Much of that is raised from grants and support from Phoenix Children’s Hospital and other local funders. About 50% is obtained from reimbursement.

The costs to run the operation, according to Christensen, are roughly $200 a patient visit, which includes medications. “It’s about $3000 per half-day clinic,” he says. Providers in the vans care for about 6 to 14 patients in a half day.

“Everybody asks, ‘What do you want?’ Most people would think I’d say I want more money so I can help kids. Really, what I want to do . . . is educate others, and the thing that I would like to tell them is that these kids are all worth it. Every time we’ve had bad outcomes or problems, we think about all the wonderful times that our kids have become incredibly successful-gone to nursing school or gotten a job,” he says.

REFERENCES

1. Children’s Health Fund. A doctor’s office on wheels. Available at: http://www.childrenshealthfund.org/healthcare-for-kids/doctors-office-on-wheels. Accessed March 18, 2015.

2. National Alliance to End Homelessness. The state of homelessness in America 2014. Available at: http://www.endhomelessness.org/library/entry/the-state-of-homelessness-2014. Published May 27, 2014. Accessed March 18, 2015.

3. Bassuk EL, DeCandia CJ, Beach CA, Berman F. The National Center on Family Homelessness. America’s youngest outcasts. Fact sheet. Available at: http://new.homelesschildrenamerica.org/mediadocs/275.pdf. Published November 2014. Accessed March 18. 2015.

4. Cohen E, Mackenzie RG, Yates GL. HEADSS, a psychosocial risk assessment instrument: implications for designing effective intervention programs for runaway youth. J Adolesc Health. 1991;12(7):539-544.

LEARN MORE ABOUT CHILDHOOD HOMELESSNESS

Randal Christensen, MD, has written a book about his experience caring for homeless youth:

Christensen R. Ask me why I hurt: The kids nobody wants and the doctor who heals them. New York: Broadway Books; 2011.

Available at: www.amazon.com/Ask-Me-Why-Hurt-Nobody/dp/0307719014

Dr. Christensen provides a description, best practices, and more at the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Healthcare Innovations Exchange in the article: “Mobile clinic provides comprehensive medical home for homeless and at-risk youth, reducing emergency department visits and increasing follow-up care.”

Available at: bit.ly/mobile-clinics

Stay tuned for more published studies. Dr. Christensen says he is involved in a large research project with the University of Arizona School of Public Health and will likely have 2 publications on mental health issues among homeless youth out this year.

Crews’n Healthmobile website:

www.phoenixchildrens.org/community/healthcare-outreach/crewsnhealthmobile

For more about the nationwide network of mobile healthcare for children, visit Children’s Health Fund:

For more about children and homelessness, go to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, youth page:

www.endhomelessness.org/pages/youth

For statistics on homelessness, visit the National Center on Family Homelessness:

America’s Youngest Outcasts report:

www.homelesschildrenamerica.org/home

Ms Hilton is a medical writer who has covered health and medicine for 25 years. She resides in Boca Raton, Florida. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.