Puzzler: 14-year-old with asthma, vomiting, and vape use presents with chest pain

Can you diagnose this patient?

The Case:

A 14-year-old girl presented to her primary care office with 2 weeks of vomiting that began when she tried to eat breakfast. She said she was feeling well up until that point, but then developed sudden onset vomiting and constant, 7/10, non-radiating chest pain centrally located at about the level of the second rib that remained unchanged since onset and slightly worsened when trying to eat. She was able to take in liquids but vomited all food, despite having an appetite. She denied feeling the food get stuck in her throat and endorsed continued vomiting of meals within 2 minutes of eating. She denied blood in the vomit and denied any abdominal pain.

Urination was unchanged, and stools, although infrequent because of a lack of eating, continued to have their normal consistency and color. The patient did endorse some mild shortness of breath. This started around the same time as the other symptoms, but did not find it very bothersome. Her last sexual encounter was 3 months prior to this visit, just prior to Nexplanon insertion. Her last menstrual period was 2 months prior to the visit.

On review of systems, she did not endorse palpitations, syncope, lightheadedness. She had increased her vape use recently but did not disclose when she started or how much she vaped. She had no recent travel and had not identified any extremity swelling. She was unsure if she had lost weight but had not been trying to lose any.

She had a past medical history including Nexplanon insertion eight weeks prior to presentation for this visit. She was told she had asthma as a younger child but had no documented diagnosis or history of treatment. She took no medications and had no allergies. She had no drug or alcohol use outside of vaping. She lived with her foster mother and was unaware of her family history.

The patient was afebrile, normotensive, with a pulse of 126 and an SPO2 of 95% on room air. Her weight was 51kg with a BMI of 20.86. Her weight 6 weeks prior to this visit was 53.1kg. She appeared uncomfortable but not in acute distress, and was able to answer questions appropriately. On respiratory exam, she had wheezing throughout all lung fields with an inspiratory pop and poor air movement. She did not use any accessory muscles for respiration. After receiving an albuterol treatment in office there was no improvement on exam, although the patient did feel subjective improvement. A cardiovascular exam demonstrated normal S1 and S2 without murmurs, rubs, or gallops. The Abdominal exam was soft and nontender throughout with normal bowel sounds and without distension.

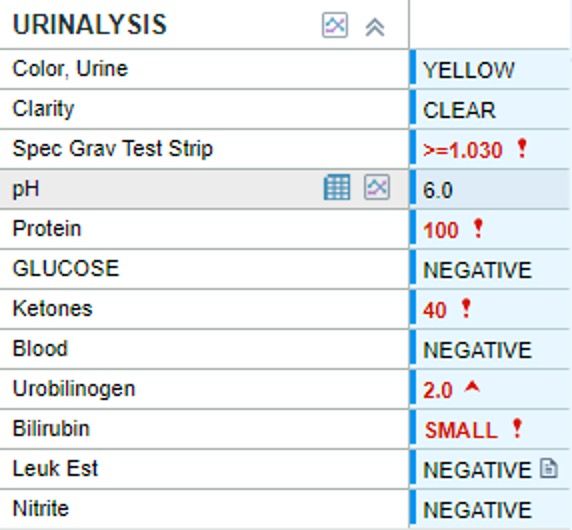

Urinalysis was obtained, which demonstrated increased specific gravity, protein, ketones urobilinogen, and small bilirubin with negative nitrites and leukocyte esterase (Figure 1). A urine B-HCG was also performed and was negative.

Diagnostic Assessment:

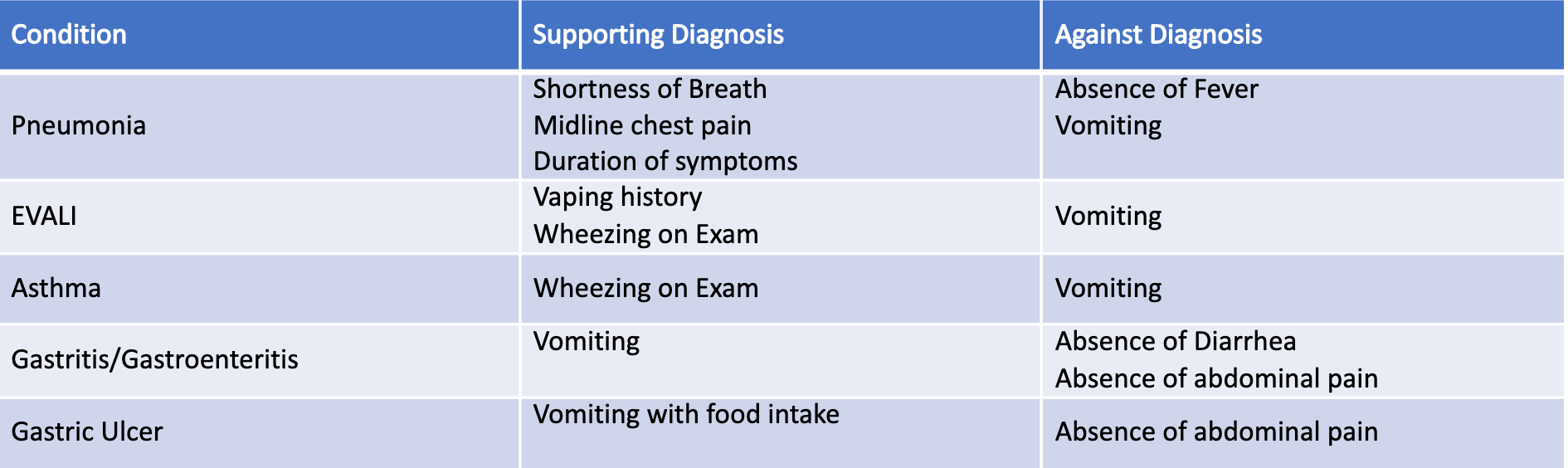

Differential diagnosis at this stage included gastritis vs gastroenteritis, gastric ulcer, asthma, EVALI, and pneumonia (Table). Gastritis and gastroenteritis could explain the vomiting but would be atypical causes of the shortness of breath. The patient also had no diarrhea or abdominal pain that may be associated with these diagnoses. Both asthma and e-cigarette and vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) in the setting of active vape use could explain the pulmonary symptoms but were less likely causes of the vomiting. Finally, pneumonia could cause the shortness of breath and cough, but no crackles were heard on pulmonary exam, and the patient had no fever for the duration of the two-week presentation. She also said that vomiting occurred after eating, unrelated to her cough.

Given her lack of objective improvement with albuterol treatment, an SPO2 of 95% on room air, and lack of explanation for the inability to take in food, she was referred to an imaging center for a chest X-Ray. Results demonstrated a left lingular pneumonia with minimal left pleural effusion and perihilar peribronchial thickening (Figure 2).

Epidemiology and Pathophysiology:

Vomiting is a frequent cause of healthcare visits in the pediatric population and includes a wide differential diagnosis, frequently from gastrointestinal infections that resolve without provider intervention1. While the pathophysiology of vomiting is multifaceted, one pathway is mechanical, by which excessive stretching or irritation of the wall of the intestine results in increased activation of serotonin and neurokinin receptors and subsequent vomiting1,2.

Community acquired pneumonia is a relatively rare diagnosis in the pediatric patient that most commonly presents with fever, cough, tachypnea, and occasionally abdominal pain3. Sequela of typical community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can include abscess formation, necrotizing pneumonia, and sepsis. While the presentation of pneumonia can vary widely, vomiting as the primary chief complaint is rare. Given the proximal nature of the stomach and lung in the pediatric patient, it is possible that mechanical disruption of the stomach by infected or inflamed lung tissue could result in such a presentation.

For patients with a possible diagnosis of CAP, differential diagnosis frequently includes asthma, as it is highly prevalent in children. With the increased use of e-cigarettes (vapes), e-cigarette and vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) is an increasingly frequent diagnosis, with over 2900 diagnoses and 68 deaths attributed to EVALI from the first diagnosed case in June of 2018 to February 20204. The treatment of each of these diseases differs widely, and thus accurate diagnosis is imperative for symptom resolution.

Therapeutic Intervention:

The patient was prescribed a 7-day course of Augmentin for her lingular pneumonia identified on chest X-Ray. Given her significant wheezing on exam and possible history of asthma, she was prescribed an albuterol inhaler for at home use and a 5-day course of oral prednisone 60mg. She was instructed to use the albuterol inhaler three puffs every 4 hours for 2 days, followed by 3 puffs, 3 times per day for 3 days.

She and her foster mother were called one day after diagnosis to assess her status. She expressed improvement in her shortness of breath and an ability to eat very small bites of food without vomiting. One week later, she returned for in-office evaluation, and she expressed significant improvement. She was able to eat without issue and felt that her shortness of breath had improved with antibiotic, albuterol, and steroid use. She had not vaped since her previous visit. On exam, she did have continued wheezing, though air movement was noted to be improved compared to her previous visit. Given her continued wheezing, she was instructed to continue using her albuterol inhaler at 2 puffs, 3 times daily for the next 5 days, followed by as-needed use.

Discussion

This patient’s presentation of vomiting with only mild shortness of breath had a wide differential. Her subjective presentation of vomiting immediately after food intake with only mild shortness of breath was a highly unique presentation of pneumonia. Her objective presentation was similarly abnormal, with exam findings of tachycardia with decreased SPO2 of 95% without fever and with diffuse wheezing without crackles. The gastrointestinal aspect of her presentation led us to expect a gastritis or gastroenteritis, but the overlying pulmonary symptoms led us towards EVALI or asthma, with a combination of the two as the presumed diagnosis.

Without benefit from a nebulizer treatment, our differential expanded to include more atypical causes, including the eventual diagnosis of pneumonia. Pneumonia has previously been identified as a cause of vomiting in the pediatric patient, but it most often presents with post tussive vomiting1.

In this case, the working hypothesis for cause of the vomitus is that the lingula of the lung, inflamed by infection, pressed against the stomach, such that when she tried to eat and the stomach received the food bolus or contracted, the irritation caused immediate vomiting.

To our knowledge, this is a unique presentation of pneumonia that has not been previously published, and with the vagueness of symptoms and immediate need for antibiotics to allow for any amount of oral intake, is an important clinical situation for providers to be aware of.

While amoxicillin is considered the first line treatment for CAP in adolescents who are fully vaccinated 5, Augmentin was prescribed for broader coverage in case of aspiration given her excessive vomiting. While identifying the causative organism of such a presentation would have been of interest, a sputum sample was not collected.

The role of vape use in this case is unclear; it is possible that vaping contributed to the entrance of pathogens to the lung parenchyma and facilitated the infectious process, or that chronic inflammation caused by sudden use of the vape impaired the immune response. Notably, the patient’s duration and extent of vape use could not be elucidated during the patient interview, so it is unclear exactly how much this may contribute.

Conclusion

This case presented a unique case of lingular pneumonia in a 14-year-old patient with overlying asthma, possibly worsened by vape use. It is imperative to include pneumonia in the differential for illnesses that may not be explained by more common diagnoses, and which do not respond to initial treatment, even when hallmark signs and symptoms of pneumonia (fever, crackles on exam) are not present.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the patient and her foster mother for giving us permission to publish this case study.

Image credits: Author provided

References:

- Shields TM, Lightdale JR. Vomiting in Children. Pediatrics in Review. 2018;39(7):342-358. doi: https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2017-0053

- Zhong W, Shahbaz O, Teskey G, et al. Mechanisms of Nausea and Vomiting: Current Knowledge and Recent Advances in Intracellular Emetic Signaling Systems. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021;22(11):5797. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22115797

- Fotsch DM, Fox J, Snedden TR. Unexpected Pneumonia Diagnosis From Pediatric Abdominal Pain: A Case Report. Journal of Pediatric Health Care. 2022;36(2):170-173. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.10.005

- Corcoran A, Carl JC, Rezaee F. The importance of anti‐vaping vigilance—EVALI in seven adolescent pediatric patients in Northeast Ohio. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2020;55(7):1719-1724. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ppul.24872

- Chee, E., Huang, K., Haggie, S., & Britton, P. N. Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines on the management of community acquired pneumonia in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2022;42:59-68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prrv.2022.01.006

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.