Spina bifida: Top 10 things for physicians to know

The pediatrician's role is to support both the child with spina bifida and the family as they come to terms with this chronic illness. This article presents the 10 actions that are most important in preparing for and caring for a child with this complex health need.

This morning your first patient is a pregnant woman you have never met. She is 28 weeks pregnant and will be having a child with spina bifida. She is anxiously looking forward to a term delivery and has already met with a neurosurgeon. She asks if you are comfortable taking care of a child with complex health needs like this.

Some physicians say that spina bifida is the most complex disorder to manage because it involves the collaboration of a long list of subspecialists who care for a long list of conditions.1,2 Although a set of spina bifida guidelines do exist, there is still a limited source of evidence or guidance from which to base many decisions.3 Anonymous patient data, however, are being collected through the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry (NSBPR), a computerized reporting and database system developed and maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).4 The NSBPR has been created to provide evidence to help determine a starting point for directions in current and future care and treatment.

Currently, most tertiary care centers offer a secondary care pediatric spina bifida clinic that allows a patient to see many subspecialists on a given day. This helps eliminate repeat visits to the center and encourages subspecialty collaboration with medical decisions, which in turn helps save costs and enhances quality.5

Because a tertiary care center is in many cases not the patient’s primary medical home, the patient with spina bifida often is also followed by a local primary care pediatrician (PCP). This article is intended to offer a review of care for these children by presenting the top 10 things a PCP should know about spina bifida. It will not cover other neural tube defects (NTDs) such as anencephaly or encephalocele.

Before pregnancy

First, consider the role of folic acid in young women wanting to become pregnant.

1. Tell young women to include 400 µg to 800 µg folic acid in their diet or by supplement before becoming pregnant. Stress this point especially to Hispanic women whose diets may contain more corn flour, which in the United States is still not fortified with folic acid.

In 1958, aminopterin, a folic acid antagonist, was noted to cause NTDs in animals. This encouraged scientists to consider how this B vitamin might be linked to NTDs in humans. After convincing evidence showed that maternal folic acid deficits could increase rates of NTDs, efforts in the United States were made to increase folic acid consumption in the maternal diet. Given that these deficits often occur before a woman realizes she is pregnant, this effort had limited impact on overall prevalence. In 1998, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finally mandated fortification of wheat flour. Since that time, we have seen a 31% decreased rate of spina bifida from 0.5 per 1000 to 0.35 per 1000 births.6,7 These rates have not decreased to the same extent in Hispanic women who likely eat more corn flour products than wheat products. Corn flour still has not been mandated to contain folic acid, although a petition is currently at the FDA.

Women with spina bifida and their female relatives should be encouraged to take a higher dose of 4000 µg of prescription folic acid during their fertile years to decrease risk of reoccurrence. A simple way to help educate young female patients prior to a pregnancy about the importance of folic acid in their diet is to refer to the CDC webpage listing cereals containing 100% of the recommended daily allowance of folic acid (400 µg): www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/cereals.html.

The basics

Spina bifida is an NTD that occurs in the first several weeks after conception. Children born with such a congenital defect will have a range of symptoms based on the level of their spinal lesion.8 These may include:

- Motor deficits in their lower extremities;

- Sensory deficits in their lower extremities and genital area;

- Genitourinary and bowel issues including incontinence and decreased male or female sexual function;

- Chiari 2 malformation and hydrocephalus;

- Learning differences; and

- Functional issues that come with living with a complex chronic illness.

Neurosurgery/neurology

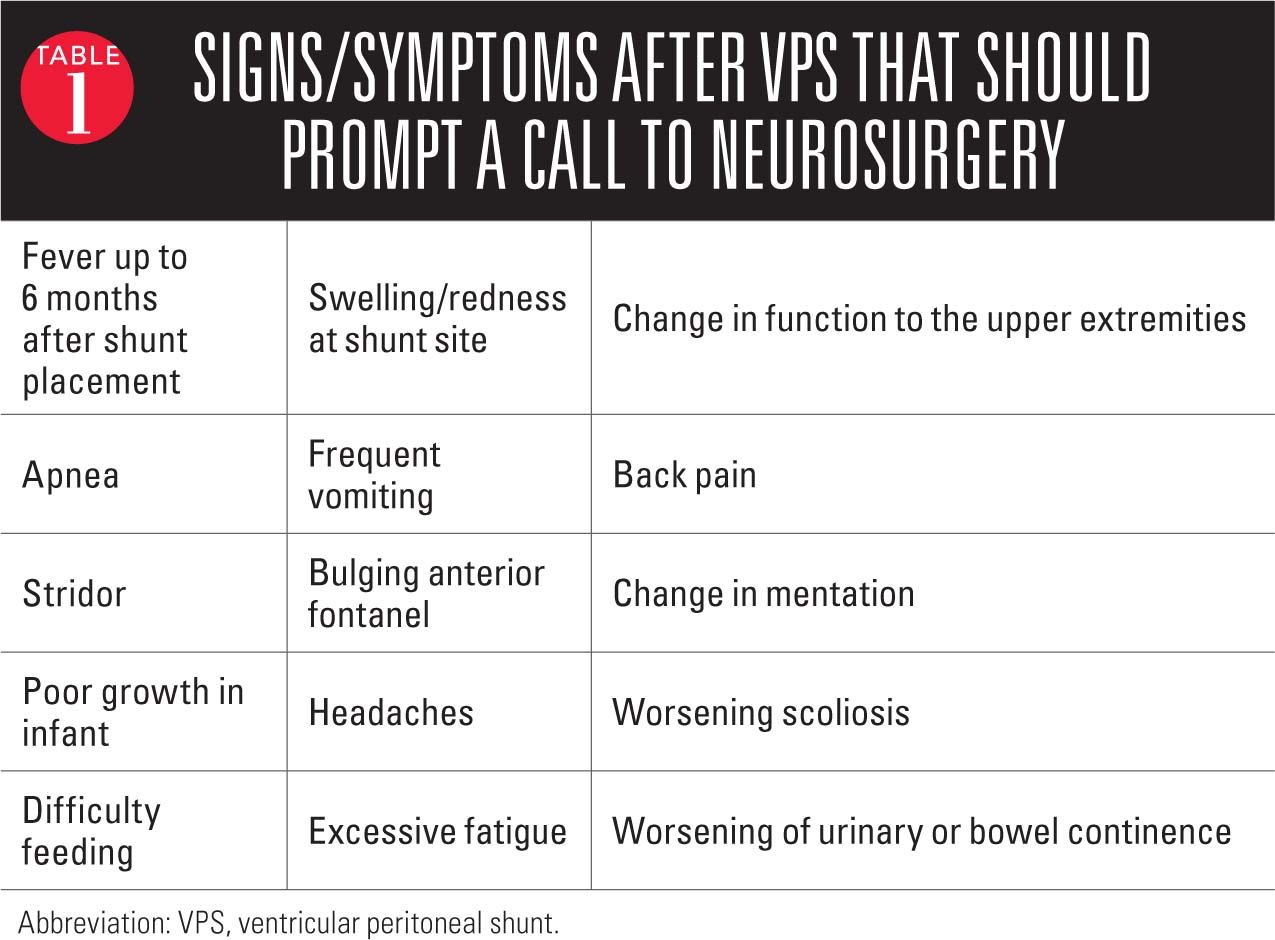

2. Learn the signs/symptoms of shunt infection/malfunction, Chiari 2 malformation, and tethering.

3. Document a detailed neurologic exam of patients to be able to recognize change.

These infants will need emergency surgery to close their open defect. This should take place in the first 24 to 48 hours to prevent infection. Ideally, a woman with a fetus with a known NTD requiring closure will deliver at a tertiary care center with a pediatric neurosurgeon to ensure sterility to the lesion and reduce trauma on transport.

After several years of study, some US centers now offer in utero closure prior to delivery.9 Although in utero repair may decrease the incidence of hydrocephalus and the severity of the Chiari 2 malformation (herniation of the cerebellar vermis, brainstem, and 4th ventricle), it will not change the spinal cord function in regard to walking or continence and has an increased risk of fetal morbidity and mortality.

SHUNT INFECTION AND MALFUNCTION

The majority of neonates who undergo postdelivery closure will survive and be among some of the healthier infants in an intensive care nursery. Because closure may change the dynamics of cerebral spinal fluid and cause a propensity for Chiari 2 herniation, approximately 85% of these neonates will require a ventricular peritoneal shunt (VPS) placement. Some centers may use a third ventriculostomy to avoid complications of living with a shunt, although this is not recommended for young infants with myelomeningocele.10 Because 15% of infants with spina bifida may not need shunting, hydrocephalus treatment may be delayed for several weeks until the need is apparent.

After initial repair, neurosurgery will closely follow clinical exam, head circumference growth, and ventricular size by radiologic imaging. Because infants have an open fontanel, they often do not become as symptomatic as older children and can tolerate increased intracranial pressure. Head circumferences crossing percentiles on a growth chart, radiologic imaging demonstrating enlarging ventricles, and clinical exam can help document the need for a shunt.

About 10% of infants who have a shunt placed may develop a shunt infection in the first 6 months after placement and more may develop a malfunction in the first 2 years after placement.11 Children with prematurity and longer hospital stays are at higher risk for shunt infection. With use of an antibiotic-coated VPS, this overall rate has decreased. Neurosurgery should be notified about all fevers, however, for the first 6 months after a shunt placement. When there is a shunt infection, the child will need to have the shunt externalized or removed and will need to complete a course of intravenous antibiotics before another one is placed.12

In the younger child irritability, esotropia, or fatigue may indicate a malfunctioning shunt whereas in the older verbal child headache or vomiting may be the obvious signs of shunt malfunction (Table 1).13 More subtle signs such as changes in school performance and cognitive abilities, excess fatigue, trouble writing, or trouble ambulating can be hints to a malfunctioning shunt. Frustratingly, at times shunt malfunction can present with or without obvious signs of increased intracranial pressure. Neurosurgery should be contacted and the patient sent to the local emergency department if there is concern about a shunt malfunction.

CHIARI 2 MALFORMATION

Despite the use of a VPS or ventriculostomy, a minority of infants may continue to have symptoms related to the Chiari 2 malformation causing pressure on the midbrain. These may include difficulty feeding secondary to a poor suck and significant gastroesophageal reflux disease leading to poor growth; stridor; respiratory distress; obstructive sleep apnea; and even death in the first year of life. In an infant, what may seem to be a symptomatic viral croup with stridor or acute gastroenteritis with vomiting may actually be life-threatening symptoms of a herniating Chiari 2 malformation.

In the older child changes to the upper extremities from a Chiari 2 malformation may cause difficulty with writing or using a manual wheelchair. Central or obstructive apnea is a significant leading cause of death in these children, and sleep apnea should be monitored closely.14 When the VPS does not control the obstructive hydrocephalus from a Chiari 2 malformation, a laminectomy to expand the foramen may be recommended although outcomes on this procedure are limited.15

TETHERED CORDS

Around 9 to 12 months after surgical repair, all patients with spina bifida will show evidence of spinal tethering on magnetic resonance imaging. When a patient’s baseline function changes, however, and the shunt is not the culprit, it may be that releasing the tethered cord will return a patient to his or her baseline and reduce the chance of losing skills permanently. Tethered cord syndrome is a clinical diagnosis that is considered when there are changes noted to a prior, well-documented physical exam and the shunt seems to be working well. Common tethering symptoms include back pain, weakness, worsening of scoliosis from muscle imbalance, and changes to bowel and bladder.16

Tethered cord syndrome often becomes a problem during periods of rapid growth when the bone is lengthening and stretching the cord, so one should consider this during ages 5 to 9 years and adolescence.17

Orthopedics

4. Have a low threshold to obtain x-rays to look for fractures in these children.

5. Routinely and thoroughly inspect insensate skin for ulcers.

“Will my child walk?” is one of the first questions asked by parents of a fetus or newborn with spina bifida. Unfortunately, sometimes the best answer is “maybe.” Although a child with a low lumbar or sacral lesion may learn to walk with assistance, as a teenager they may opt for the quicker way of a wheelchair to keep up with friends. Some spina bifida clinics introduce wheelchairs earlier while others encourage children to continue to walk, even for those who are braced higher, although ulcers and infections may prevent consistent ambulation.18

From early on, these children will need the support of an orthopedist and a physical therapist or physiatrist to help figure out the healthiest way to maintain appropriate neutral positioning and to move in the appliances the child may need to use for ambulation. Ankle foot orthotics or higher bracing may help a child ambulate, but these will need to be replaced as their feet grow. Some orthotists may agree to come directly to a school to fit a child for a new set. Wheelchairs can be replaced every 5 to 10 years based on insurance. Local area organizations may help families without insurance to pay for or find used equipment.

Even the child with a high lesion should be encouraged to spend time in a standing position. This helps with bone calcification as well as growth. Without a lot of standing that leg will be shorter than expected and more prone to fractures.

Based on the child’s spina bifida functional level, certain muscle groups may work while the opposing muscle group may not, leaving joints with inappropriate traction. This may lead to contractures or positioning that is inappropriate for sitting and standing. Inappropriate positioning can lead to sores and dislocations as well as falls with attempts at ambulation or transfers. Because these children have an insensate area on their lower extremities, their painless fractures or bedsores may not be obvious without careful inspection. A swollen area on a leg mistaken for a contusion may actually represent a complex growth plate fracture that will impact further growth of that bone. A young woman in skinny jeans may develop a pelvic sore from the tightness and rubbing of her pull-up. This sore can easily spread to a pelvic osteomyelitis if not discovered.

Encouraging families to monitor calcium and vitamin D intake in a child’s diet is an important piece of anticipatory guidance. The child with initially low vitamin D levels may be placed on vitamin D. Given that these children are at risk for calcium renal calculi, however, careful reevaluations of vitamin D level and calcium intake should be undertaken.

Frequent examinations for scoliosis also will be important to help create appropriate positioning to prevent sores or to intervene with bracing to prevent worsening respiratory status. Spinal fusion, a complex surgery with a long recovery time, can help straighten a spine and maintain or improve inadequate respiratory status.

Encouraging exercise will offer this child an improved quality of life, decrease stress, prevent deconditioning, help with ambulating and transfers, prevent obesity, resist infections, and even improve constipation. Contacting local adaptive sports agencies such as Special Olympics or YMCAs and inquiring about swimming or aquatic therapy, hippotherapy, adaptive skiing, and adaptive bikes can make this more fun.

There is a lot of information to understand and learn to keep on top of this patient’s health. Communication with a spina bifida team and the subspecialists involved will help PCPs guide many families on a complex path to improved health and wellness.

The continued discussion focuses on urology, bowel programs, education, and anticipatory guidance.

Urology

A pediatrician's job includes supporting a child and family with their frustration and anger as they come to terms with a chronic illness. Encouraging the development of resilience often found in these children will be critical to the long-term goal of functional independence.19 This may mean being an available support to a depressed parent or patient, an available school advocate, and offering creative solutions to upsetting medical problems.

One of the more challenging components of spina bifida is the potential for urinary and fecal incontinence. It may not be easy to achieve full continence. Social continence, or continence during the school or work day, however, is a very achievable goal for many children. This will not typically happen without a lot of early family education, support, and practice to find the right balance of dietary modifications, medications, time, and effort.

6. Understand the risks and differences between a high-pressure and low-pressure bladder.

7. Do not treat all positive urine cultures in patients who use clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) unless clinically indicated.

When the use of VPS in the 1960s dramatically prolonged the life of children with spina bifida, kidney disease became the next major cause of morbidity and mortality impacting these children. Pediatric urologists today have helped lessen the rate of kidney failure significantly, but renal failure continues to be one of the leading causes of death in patients with spina bifida after the first year of life.20 Although most children will have some degree of bladder dysfunction, 30% to 40% will develop renal dysfunction as well.21

A bowel program must be in place before starting urinary potty training. As with any child, parents should look for signs of diaper dryness for 2 to 3 hours before starting habit training. When the bladder and sphincter are without appropriate neurologic wiring, however, their actions can be nonfunctional and make potty training in the typical way impossible. Impaired autonomic nerves can lead to a lack of sensation of fullness, decreasing the ability to be aware of impending urinary leakage.

The bladder, which may already be under high pressure from a noncompliant bladder wall, may have intermittent nonfunctional contractions against a closed sphincter causing higher pressure in the bladder. This high pressure can cause reflux and hydronephrosis and change the bladder wall lining, causing it to be even less compliant. This can spiral downward and “drown” and damage the kidneys, leading to recurrent episodes of pyelonephritis and scarring, urinary stones, and urinary incontinence.

Based on results of urodynamics, a test to measure the pressure in the bladder at rest and during voiding, efforts are made to improve the overall health of the renal system. When a high-pressure bladder is found, treatments are aimed at decreasing the bladder pressure and may include:

- Use of medications to decrease the high muscle tone around the bladder and sphincter;

- Periodic CIC of urine;

- Use of injectable agents such botulinum toxin (Botox) or dextranomer hyaluronic acid polymers (Deflux) to treat reflux; and

- Surgeries to increase the size of the bladder.

When urodynamic testing demonstrates a low-pressure bladder, patients may experience frequent urinary leakage. Efforts may be made to:

- Increase sphincter resistance using injectable agents or artificial sphincters; and

- Offer surgeries to increase bladder size or increase sphincter resistance (bladder sling).

Most children who catheterize will likely have white blood cells in a urinalysis and will grow bacteria in a urine culture even when they do not have a true infection. This does not always mean they have an infection requiring treatment. Urine should be sent for laboratory culture evaluation when a patient shows signs or symptoms: fever, abdominal or back pain, vomiting, or incontinence between catheterizing times. One should try to balance the importance of treating obvious infections against urine cultures obtained when urinary tract infections (UTIs) are less likely. Cultures obtained with every cough and cold may lead to overzealous use of antibiotics and development of antibiotic resistance. A true culture-positive symptomatic UTI may be treated with only 3 days of antibiotics, whereas pyelonephritis will require longer treatment.

Issues with compliance to catheterizing and taking medications may become more difficult when control is transitioned from parent to the teenager. Feelings of depression, anger, and poor self-esteem are common with incontinence as well as living with a chronic illness. Offering some flexibility and advocacy will go far to preserve renal function. Can the patient catheterize at a more convenient time, such as during an elective time instead of at a social lunch hour? Does this patient have a safe, private, and effective place to catheterize? Use of a nursing office instead of a typical bathroom without a place to put supplies should be considered.

A wheelchair-bound girl should be encouraged to work toward a way to catheterize herself independently with a Mitrofanoff (a surgical procedure in which the appendix is used to create a conduit from the bladder to the abdominal wall). Otherwise, she will be dependent on others to transfer her from her chair, undress her, catheterize her, redress her, and transfer her back to her chair. An extra set of clothes needs to be kept at school, and the patient needs to know whom to contact for help if the nurse is not available. Some boys may prefer to use discrete boxer pull-ups instead of diaper-like pull-ups. Families with Medicaid should be offered a prescription for diapers with the diagnosis of urinary or fecal incontinence with sensory unawareness.

Yearly renal labs and blood pressures also can assist in ensuring the integrity of the system.

Bowel programs

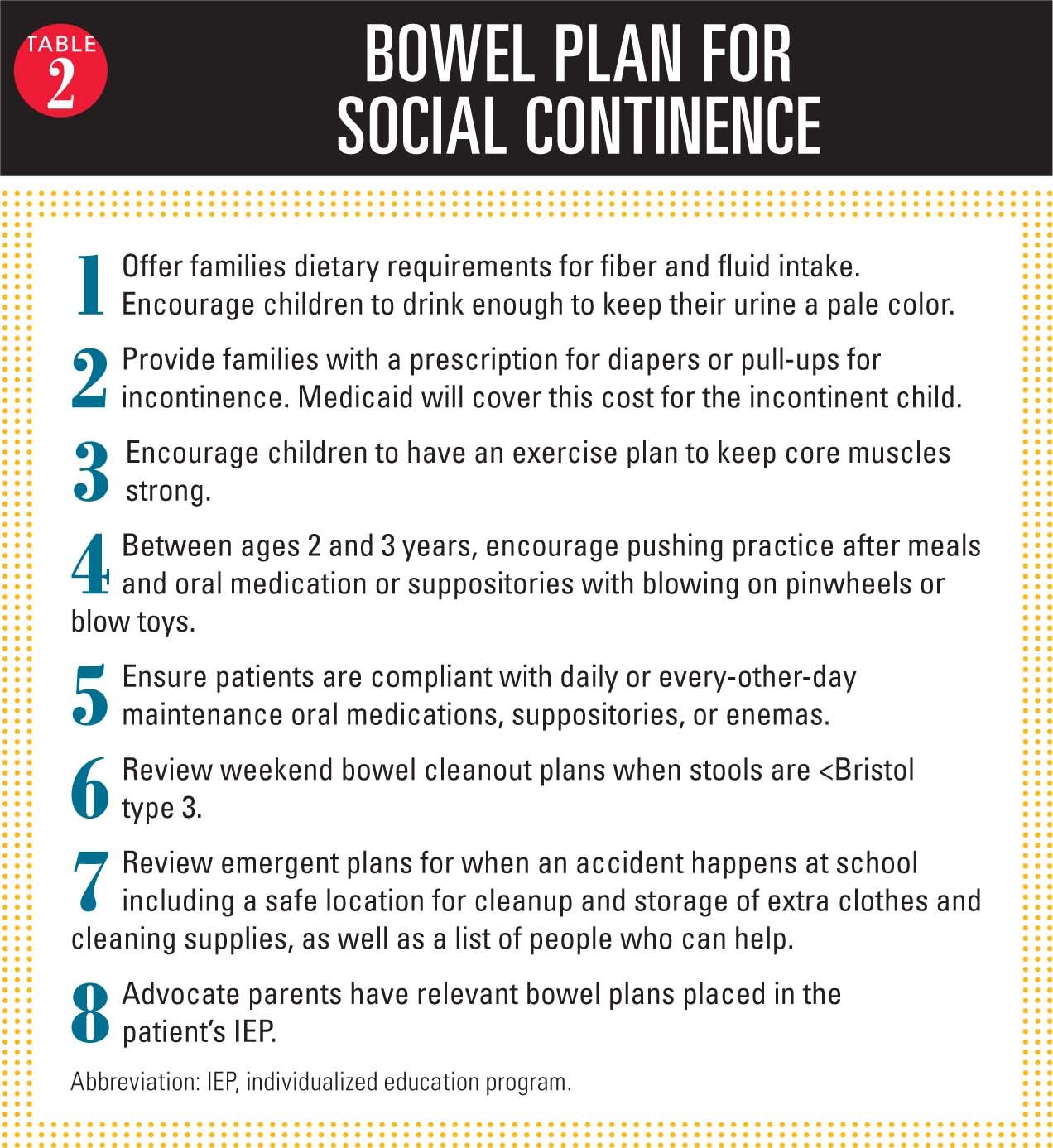

8. Encourage families to develop an early bowel program that can offer bowel continence most of the time.

Along with atonic bladder, children with spina bifida also may have an atonic bowel, a nonfunctioning anal sphincter, and no sensation for a need to have a bowel movement. This can lead to fecal retention, chronic constipation, encopresis, and fecal incontinence, which can certainly lead to bullying, decreased quality of life, urinary incontinence, UTI, bowel obstruction, and even an increased chance of colon cancer.22

There is limited evidence on bowel management in the pediatric spina bifida population. One cohort study with 80 children aged between 5 and 18 years showed that despite best efforts 30% remained diaper dependent and only 10% were continent; however, 60% had social continence with no more than 1 accident per week.23 Similar to the inability to predict whether a child with a low lumbar level lesion may be a wheelchair user versus a crutch user, families can be frustrated in the younger years not knowing if their child will be able to achieve stool continence. Even at the same spinal level, parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves may influence what happens in terms of continence more than the spinal level of their spina bifida.

One hopes to offer the family a time-efficient and flexible plan to eliminate stool that will allow the child to manage independently at some point. The hope is that children will learn to manage well enough to avoid the social isolation that correlates strongly with incontinence.24 Parents will also need to understand that bowel continence is altered by many different factors and children will have better weeks and worse weeks. It will be critically important for parents to be able to recognize clues that will let them know when to alter medication dosages from the agreed-on bowel plan. Patients, parents, and PCPs should have a copy of the Bristol stool chart (available online at http://bowelcontrol.nih.gov/Bristol_Stool_Form_Scale_508.pdf) to make an often-nebulous stool description more empiric.25 The urologist, pediatric gastroenterologist, or a general pediatrician associated with the spina bifida clinic can help offer advice on the bowel plan.

Teaching parents about a bowel program should start in the first year of life (Table 2). It should be reiterated that parents should carefully monitor stool consistency and avoid constipation. They should ensure that enough fluid is going in so that the urine remains light yellow to clear. They can introduce solids that are high in fiber and avoid foods that will contribute to constipation. (Rice cereal may be worse than oat cereal, and prunes and orange vegetables should be routinely included.) Encouraging parents to include fruits and vegetables early in life and on a daily basis will help maintain this habit. Meeting with a nutritionist may help families devise menus and find high-fiber recipes they can use every day.

Starting a suppository routine at a younger age lets children know that this is part of their daily routine. Some parents of preschool-aged children may opt for use of daily oral medications such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) to ensure that their child has a likely bowel movement in a diaper/pull-up. As the child moves to a goal of social continence, the unpredictably timed bowel movement from PEG may lose its allure. Parents should commit to a stool medication program that allows them social continence a year before primary school starts. Determination of the child’s anal sphincter tone and transit time will help determine whether a daily oral medication such as senna, a suppository, or an enema is a better option for social continence at school and a predictably timed stool at home. Tracking frequency of bowel movements and Bristol chart scores can help families figure out what daily medications work best for them.

When enemas are the system that works best to offer social continence, some teenaged patients can consider having a Malone or a Chait cecostomy placed for antegrade enemas through a surgically placed stoma. This may allow for a longer time of continence between enemas and offer independence to the wheelchair-bound patient. Although antegrade bowel washouts may take 1 to 2 hours of required toilet sit time, it may allow for continence and independence as patients transition to adult life.

Families should also have a “what if the Bristol score is <3 plan” so they can get back to a better stool pattern and ideally prevent constipation complications. Use of high-dose PEG and enemas in the “what if” plan is best done on Fridays or Saturdays to reduce late effects during the next school day.

Educational differences

9. Screen for organic attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and provide information about learning differences in children with spina bifida.

Although these children are typical in many ways, there are educational differences that require the attention of the pediatrician.

The majority of children with spina bifida have learning differences. Early intervention will likely offer developmental services in the first 3 years of life. Encourage all families to consider educational evaluations and reevaluations by their local school or ideally with specialists familiar with spina bifida. Most children without significant cognitive deficits can receive a 504 plan for other health needs.

It is common to see issues with executive function including comprehension, organization, memory, sequencing, problem solving, as well as attention, hyperactivity, and perceptual motor issues. Ideally, the school will need to figure out the best way to test for and address these executive functions with comprehensive evaluations, tutoring, and therapies. Consider evaluations for ADHD and behavioral and medical treatment. These children have different brains than typical children and organic reasons for ADHD.26 The Spina Bifida Association has easy-to-access handouts regarding these educational differences that the PCP or parents can print and bring to school.

Anticipatory guidance for healthcare maintenance

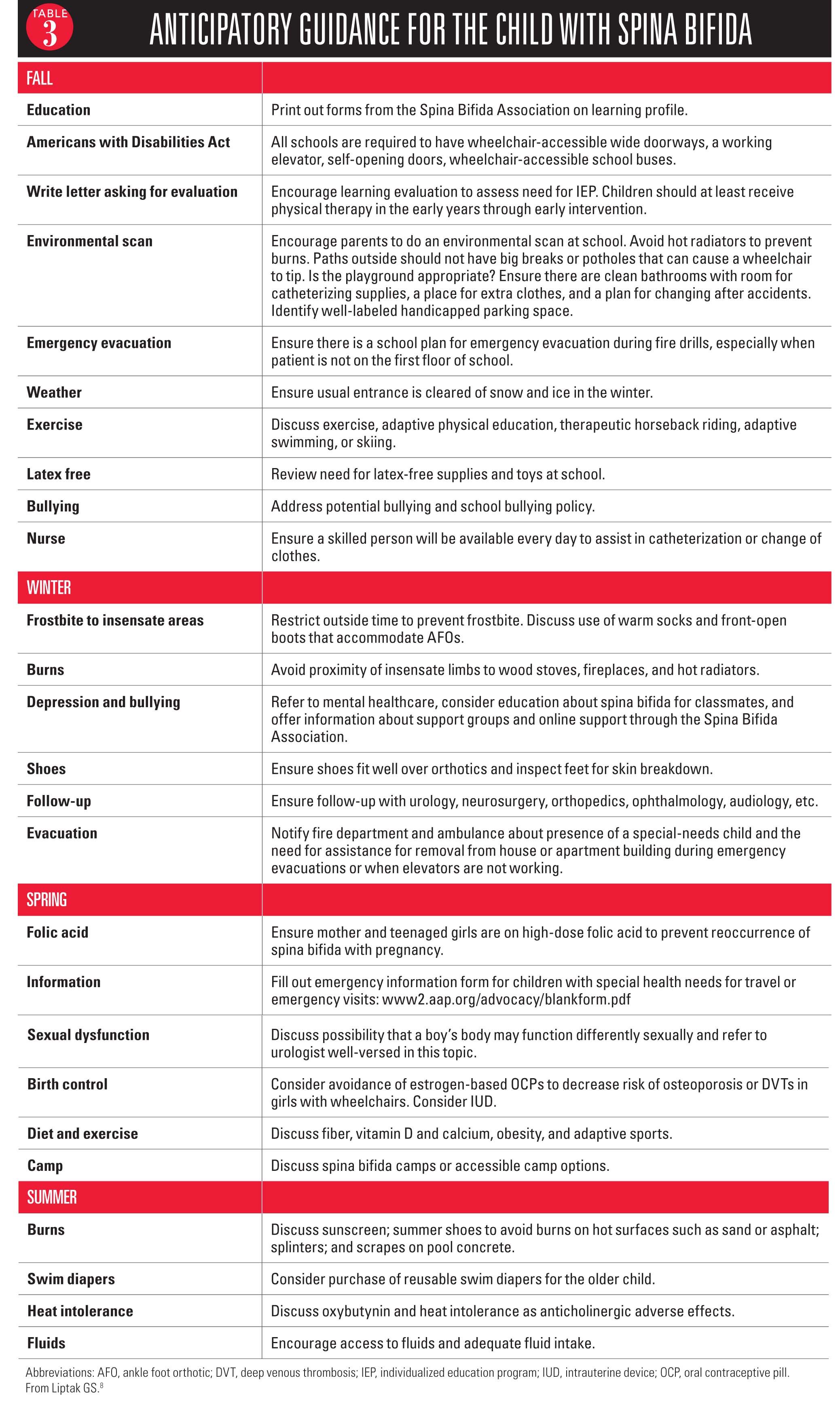

Make healthcare maintenance appropriate for these patients.

Offering advice to typical patients is a routine part of practice, but offering advice to these children requires some thought as to their needs and what is relevant. An appropriate anticipatory guidance list divided per season is listed in Table 3.8 Again, patients should be also referred to the Spina Bifida Association website.

Finally, it is very important to congratulate the parents of each new patient with spina bifida. Be certain to reassure them that you are up to the task of caring for their child, communicating frequently with the subspecialists, and supporting the family.

Thank you to Ardis Olson, MD, and Kathy Doton, MSN, RN, who encouraged my involvement with the care of these patients and the writing of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Bunch WH, Cass AS, Bensman AS, Long DM. Modern Management of Myelomeningocele. St. Louis, MO: Warren H. Green; 1972.

2. Liptak GS, El Samra A. Optimizing health care for children with spina bifida. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16(1):66-75.

3. Merkens MJ, ed. Guidelines for Spina Bifida Health Care Services Throughout the Lifespan. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: Spina Bifida Association; 2006.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Spina bifida. Findings from the National Spina Bifida Patient Registry. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/spinabifida/nsbprregistryfindings.html. Updated August 5, 2014. Accessed November 24, 2014.

5. Kaufman BA, Terbrock A, Winters N, Ito J, Klosterman A, Park TS. Disbanding a multidisciplinary clinic: effects on the health care of myelomeningocele patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1994;21(1):36-44.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Spina bifida and anencephaly before and after folic acid mandate–United States, 1995-1996 and 1999-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(17):362-365.

7. De Wals P, Tairou F, Van Allen MI, et al. Spina bifida before and after folic acid fortification in Canada. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2008;82(9):622-626.

8. Liptak GS. Spina bifida. In: Osborn LM, DeWitt TG, First LR, Zenel JA, eds. Pediatrics. 1st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1168-1174.

9. Adzick NS, Thom EA, Spong CY; MOMS Investigators. A randomized trial of prenatal versus postnatal repair of myelomeningocele. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(11):993-1004.

10. Jernigan SC, Berry JG, Graham DA, Goumnerova L. The comparative effectiveness of ventricular shunt placement versus endoscopic third ventriculostomy for initial treatment of hydrocephalus in infants. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014;13(3):295-300.

11. Kestle J, Drake J, Milner R, et al. Long-term follow-up data from the Shunt Design Trial. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2000;33(5):230-236.

12. Tamber MS, Klimo P Jr, Mazzola CA, Flannery AM. Pediatric hydrocephalus: systematic literature review and evidence-based guidelines. Part 8: management of cerebrospinal fluid shunt infection. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2014:14(Suppl):60-71.

13. Garton HJ, Piatt JH Jr. Hydrocephalus. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51(2):305-325.

14. Jernigan SC, Berry JG, Graham DA, et al. Risk factors of sudden death in young adult patients with myelomeningocele. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2012;9(2):149-155.

15. Tubbs RS, Oakes WJ. Treatment and management of the Chiari II malformation: an evidence-based review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2004;20(6):375-381.

16. Bowman RM, Mohan A, Ito J, Seibly JM, McLone DG. Tethered cord release: a long-term study in 114 patients. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2009;3(3):181-187.

17. Hertzler DA 2nd, DePowell JJ, Stevenson CB, Mangano FT. Tethered cord syndrome: a review of the literature from embryology to adult presentation. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;29(1):E1.

18. Brinker MR, Rosenfeld SR, Feiwell E, Granger SP, Mitchell DC, Rice JC. Myelomeningocele at the sacral level. Long-term outcomes in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76(9):1293-1300.

19. Turkel S, Pao M. Late consequences of pediatric chronic illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2007;30(4):819-835.

20. Oakeshott P, Hunt GM. Long-term outcome in open spina bifida. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(493):632-636.

21. McLone DG, Bowman RM. Overview of the management of myelomeningocele (spina bifida). UpToDate, Waltham, MA. Accessed November 7, 2014.

22. Nanigian DK, Nguyen T, Tanaka ST, Cambio A, DiGrande A, Kurzrock EA. Development and validation of the fecal incontinence and constipation quality of life measure in children with spina bifida. J Urol. 2008;180(4 suppl):1770-1773.

23. Vande Velde S, Van Biervliet S, Van Renterghem K, Van Laecke E, Hoebeke P, Van Winckel M. Achieving fecal continence in patients with spina bifida: a descriptive cohort study. J Urol. 2007;178(6):2640-2644.

24. Sandler AD. Living with Spina Bifida: A Guide for Families and Professionals. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press; 2004.

25. Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32(9):920-924.

26. Dennis M, Barnes MA. The cognitive phenotype of spina bifida meningomyelocele. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2010;16(1):31-39.

RESOURCES FOR PHYSICIANS AND PARENTS

WEBSITES

Spina Bifida Association:

www.spinabifidaassociation.org

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (list of folic acid-fortified cereals):

www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/folicacid/cereals.html

PATIENT HANDOUTS

Education issues:

Bristol stool chart:

http://bowelcontrol.nih.gov/Bristol_Stool_Form_Scale_508.pdf

Travel information form for children with special needs:

www2.aap.org/advocacy/blankform.pdf

BOOKS

Driscoll J, Benge J, Benge G. Determined to Win: The Overcoming Spirit of Jean Driscoll.

Leibold S; Spina Bifida Association. Bowel Continence and Spina Bifida.

Lutkenhoff M. Children with Spina Bifida: A Parents’ Guide.

Lutkenhoff M, Oppenheimer SG. SPINAbilities: A Young Person’s Guide to Spina Bifida.

Dr Wenger is a faculty member in the Division of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, Boston Medical Center, Massachusetts. She has nothing to disclose in regard to affiliations with or financial interests in any organizations that may have an interest in any part of this article.