Treating colds: Keep it simple

The common cold can make children--and parents, too--uncommonly miserable. What approaches can pediatricians recommend? The authors examine the options and suggest restraint.

Treating colds: Keep it simple

By Diane E. Pappas, MD, JD, Gregory F. Hayden, MD, and J. Owen Hendley, MD

The common cold can make children and parents, toouncommonly miserable. What approaches can pediatricians recommend? The authors examine the options and suggest restraint.

Runny noses, nagging coughs, and sleepless nights alert parents and pediatricians alike to the fall and winter seasons when respiratory viruses take their greatest toll. Upper respiratory tract infection (URI), also known as the common cold, is one of the most frequent childhood illnesses and often leads to medical evaluation. Children are particularly affected because they have not yet acquired immunity to most of the causative viruses, and they have frequent, close exposure to other children with URIs in child-care centers and schools.

The average preschooler has six to 10 colds per year, with each illness lasting 10 to 14 days. Most URIs are self-limited, but some are accompanied or followed by reactive airway disease, otitis media, sinusitis, or other complications.

Colds take a toll on parents as well as children in lost sleep, lost time from work, and the frustration of dealing with a child made miserable by cold symptoms. Advising harried parents about how best to manage these trying illnesses can be a difficult task for the pediatrician.

The epidemiology of colds

Colds occur in yearly epidemics, beginning in early fall and continuing until spring. With the onset of cold weather, people move indoors and spend more time in close contact with one another, facilitating transmission of cold viruses. Certain viruses may survive for more than 24 hours in the low humidity of heated homes.

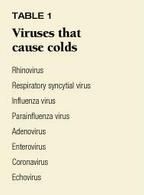

Rhinovirus, with at least 100 serotypes, is responsible for one third to one half of all colds. Other common pathogens in children under 4 years of age include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus (Table 1).1 In older children, coronaviruses, echovirus, and enteroviruses also may cause colds.

During the peak cold season, different cold viruses move through the community in a more or less predictable fashion in temperate climates. Beginning in September, rhinovirus infections rise sharply, followed by parainfluenza viruses in October and November. Infections caused by coronaviruses and RSV increase during the cold winter months, and influenza A virus peaks in mid- to late winter. A small peak of rhinovirus infection often brings the cold season to a close.1 A low rate of adenovirus infection is present throughout the cold season.

How cold viruses attack the body

A cold starts when one of the many causative viruses is deposited in the nose or conjunctiva. The virus penetrates the protective layer of nasal mucus and infects the nasal mucosa.2 Within 24 hours, symptoms develop in susceptible individuals as cytokines and other inflammatory mediators are released.1

Vascular dilatation occurs initially, producing erythema and congestion of the nasal mucosa along with increased vascular permeability, which causes local tissue edema. Serum proteins, including immunoglobulins, flood the nasal secretions. Neutrophils also accumulate, summoned by potent chemoattractants.1 The increase in neutrophils may produce a yellow or white nasal discharge. Myeloperoxidase and other enzymatic activity associated with neutrophils may cause green discoloration of the discharge.1 The nasal mucosa remains intact, although mucociliary transport is markedly reduced.3 Viral shedding peaks during the first two to four days after inoculation, typically one to three days after symptoms are evident.

Fluid commonly accumulates in the sinuses during the course of an uncomplicated cold. In one study, CT scans revealed sinus abnormalities in 87% of young adults with colds of average severity. These abnormalities may be caused either by inflammation of the upper airway, which obstructs sinus drainage, or by direct viral infection of the sinus cavities resulting in viral rhinosinusitis. Although participants in the study received no antimicrobial treatment, follow-up CT scans taken two to three weeks later showed resolution or marked improvement of the sinus abnormalities.4

Symptoms: Misery in many forms

The common cold in children often begins with constitutional complaints, including fever, headache, malaise, and myalgias during the first few days, which may disappear when the respiratory symptoms begin.5 As upper airway inflammation progresses, nasal stuffiness, sneezing, sore throat, and cough develop.

Initially, nasal discharge is clear and watery, but it becomes thickened and colored over the first few days of illness. The presence of colored, thickened nasal discharge correlates with the influx of neutrophils (PMNs) into the nasal secretions. An increase of PMNs may cause a yellow or white color, while enzyme activity associated with PMNs (such as myeloperoxidase) may cause green secretions. The presence of such colored secretions does not signify development of a secondary bacterial sinusitis. The drainage remains thickened for several days and then returns to a watery discharge before resolution of the cold.

Eustachian tube dysfunction, as evidenced by transient middle ear pressure abnormalities, is common. It is unclear whether the dysfunction results from viral infection of the middle ear mucosa or is secondary to the nasopharyngitis caused by the cold viruses.

Other symptoms may include loss of smell, hoarseness, and decreased appetite. Nasal congestion disrupts sleep and leads to fatigue and irritability.

Nasal and pharyngeal symptoms and cough peak during the early days of the illness6 but typically last as long as 10 to 14 days. Persistence of rhinorrhea without improvement for longer than 10 days suggests the possibility of a complicating sinusitis.5

How colds spread

Colds are transmitted in a variety of ways at home and in child-care settings. Small particle aerosols generated by coughing may be inhaled, large particle aerosols may land on conjunctival or nasal mucosa, and infectious secretions may be spread from person to person by direct contact.1

Studies of young adults at the University of Virginia showed that rhinovirus is often present on the hands of infected individuals and that the virus is efficiently transferred from an infected person's hand to another person's hand during brief contact and from that person's hand into his nose or eye. Sneezing and coughing were inefficient methods of transferring rhinovirus infection to others.6

Viral concentrations are high in nasal secretions and relatively low in saliva. Thus, transmission commonly occurs when an infected child contaminates his own hands with infectious secretions from his nose through nose blowing, wiping, and picking. He then touches another person (or an intermediate object) with his soiled hands. The unsuspecting recipient touches his own nose or eyes with his now contaminated hands, and the virus is delivered to the upper airway of a new host. Rhinoviruses can survive on human hands for up to two hours and on environmental surfaces for several days. The viruses can be removed from hands easily by washing or even rinsing, however.

Is it a cold, or something else?

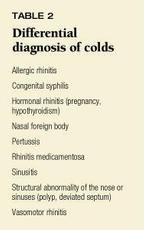

The signs and symptoms of the common cold are nonspecific and easily confused with a number of other conditions (Table 2). Allergic rhinitis can cause significant rhinorrhea, but this may be seasonal, watery (never becoming thicker or whitish), unaccompanied by fever, and associated with other signs of allergy such as nasal itching (and the "allergic salute"), allergic "shiners," eczema, and asthma. Microscopic examination of nasal mucus using Hansel's stain reveals numerous eosinophils, confirming a clinical suspicion of allergic rhinitis and suggesting a therapeutic trial of an oral antihistamine, nasal cromolyn, or steroid.

Structural abnormalities of the nose and sinuses also may cause persistent rhinorrhea. If the discharge has an intense odor, consider the possibility of a foreign body in the nose. Another cause of rhinorrhea is rhinitis medicamentosa, associated with prolonged use of decongestant nose drops or nasal spray.

Colds plus: Potential complications

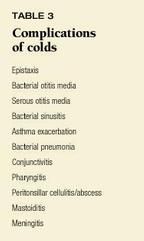

Although the symptoms of most URIs are mild or moderate and resolve in a week or two, complications may occur (Table 3). Eustachian tube dysfunction is common. Studies in adults show that over 70% of individuals infected with rhinovirus develop eustachian tube dysfunction soon after viral inocululation.1 Acute bacterial otitis media may complicate URIs in children.1 Viruses commonly isolated from middle ear fluid of children who sought medical attention for acute otitis media and had tympanocentesis performed to determine the cause included RSV, parainfluenza viruses, and influenza viruses.7

Bacterial sinusitis, a secondary infection of the paranasal sinuses, is another possible complication of URIs, but the exact frequency of its occurrence is unclear. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common causative pathogen. Acute sinusitis caused by Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis occurs less often. Bacterial sinusitis usually presents in children as either persistent or severe respiratory symptoms. Persistent symptoms include nasal discharge of any quality, clear or purulent, lasting more than 10 days without improvement and sometimes daytime cough. Fever, if any, is low. Headache and facial pain are rare in children. Severe symptoms include purulent nasal discharge and high fever (greater than 39° C). Acute sinusitis resolves spontaneously in as many as 45% of affected children.5

Viral sinusitis commonly occurs during the course of an uncomplicated URI. In a study of young adults, 87% demonstrated abnormalities of the paranasal sinuses on CT scan during the acute phase of illness. Most resolved spontaneously on follow-up.1

Colds also can lead to wheezing. Viral URIs may exacerbate reactive airway disease or asthma in susceptible children. Certain viral infections, such as RSV, adenovirus, and parainfluenza, may naturally progress to involve the lower airway, causing bronchiolitis in infants and young children. Increasing evidence suggests that children with severe bronchiolitis caused by RSV have respiratory abnormalities, including recurrent airway reactivity and abnormal pulmonary function tests, that may persist for years.

Other complications of the common cold are conjunctivitis, nasal bleeding, transient hearing loss caused by eustachian tube dysfunction and accumulation of fluid in the middle ear, peritonsillar disease, mastoiditis, and meningitis. URI may also lead to bacterial pneumonia. Antibiotic treatment of URI in children does not prevent progression to pneumonia.

Treatment: Does anything work?

"[T]he desire to take medicine is one feature which distinguishes man, the animal, from his fellow creatures. It is really one of the most serious difficulties with which we [physicians] have to contend."8

Sir William Osler

The misery produced by cold symptoms has led to the development of more than 800 over-the-counter cough and cold preparations in the United States intended to relieve nasal congestion, rhinorrhea, cough, and other symptoms.9 Antihistamines, decongestants, antitussives, expectorants, analgesics, and combinations of these products are marketed in many forms for patients of all ages. One recent survey revealed that almost 40% of preschoolers had been treated with one or more OTC medications in the preceding month, with acetaminophen and cough/cold medicines enjoying equal popularity. The children were most likely to have been treated for a cold and a runny nose.10 Unfortunately, little scientific evidence supports the efficacy of OTC products for relieving the symptoms of the common cold in children.

Because colds are self-limited and the symptoms are largely subjective, any treatment has the potential for a substantial placebo effect. Blinding of patient, parent, and physician is thus critical to effective evaluation of cold therapies. At present, no antiviral agents are available to treat the cold, and few studies demonstrate benefits for symptomatic remedies in children.

Decongestants. Systemic sympathomimetic decongestants, including pseudoephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, and phenylephrine, are often used to treat nasal congestion associated with the common cold. They reduce congestion by causing vasoconstriction. Pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine are well-absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and are excreted unchanged in the urine. Phenylephrine has variable bioavailability when taken by mouth because it undergoes extensive biotransformation in the GI tract and liver.11 Peak concentrations of these agents are reached 30 minutes to two hours after administration. Half-lives are short, ranging from two and one-half hours for phenylephrine to six hours for pseudoephedrine.

Possible side effects include tachycardia, irritability, sleeplessness, hypertension, headaches, nausea, vomiting, dysrhythmias, and seizures.12 Dystonic reactions also may occur. Patients taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors may suffer hypertensive crises. Phenylpropanolamine has been associated with cardiomyopathy, hallucinations, hypertensive encephalopathy, intracranial hemorrhage, stroke, and psychosis.13

In adults, both pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine have proved effective in reducing nasal symptoms, including congestion and sneezing, although many patients experienced side effects.9 There are no studies documenting similar benefits in children. One study of a decongestant/antihistamine combination (phenylpropanolamine/ brompheniramine) in children between 6 months and 5 years of age found no improvement in rhinorrhea, nasal congestion, or cough for those treated with the combination drug compared to placebo.12

Topical decongestants, including oxymetazoline but not tramazoline, appear effective in reducing nasal congestion in adults, although their use is limited by the risk of significant rebound congestion when the medication is discontinued. These drugs have not been studied in children, but some have suggested that rebound congestion could cause obstructive apnea in infants who are preferential nose breathers. A study in children 6 to 18 months of age showed that topical phenylephrine did not decrease nasal obstruction or alter middle ear pressures significantly during a URI.14

Antihistamines are commonly used to treat cold symptoms even though research has shown clearly that histamine levels in nasal secretions do not increase during a cold and histamine therefore is not the chemical mediator responsible for cold symptoms. Instead, mean kinin levels rise dramatically as cold symptoms become more severe, implicating the kinins as one of the mediators that cause cold symptoms.

Antihistamines can be divided into two categories. First-generation antihistamines include triprolidine, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, and chlorpheniramine. They affect the central nervous system, causing side effects such as sedation, paradoxical excitability, dizziness, respiratory depression, and hallucination. An overdose may have severe CNS effects, including coma, seizures, dystonia, and psychosis. Gastrointestinal side effects are also common.15

Cardiovascular effects may include tachycardia, heart block, and arrhythmias.15 First-generation antihistamines are anticholinergic, causing dry mouth, blurred vision, and urinary retention. They may also reduce secretions.15

Second-generation antihistamines include terfenadine, astemizole, loratidine, and cetirizine. They cause fewer CNS effects than the first-generation antihistamines. Sedation is less common, and anticholinergic effects do not occur. Overdose, however, may cause serious CNS or cardiovascular impairment.15

Several studies in adults suggest that first-generation antihistamines provide modest symptomatic relief of some cold symptoms. One study showed a 35% to 40% reduction in symptoms in patients treated with chlorpheniramine, with significantly less sneezing and a higher mucociliary clearance rate. Objective measures of nasal congestion and eustachian tube dysfunction did not show improvement, however.16

Another study showed that adults treated with chlorpheniramine had significantly fewer objective signs of a cold and reported significant improvement in cold symptoms compared to those who received placebo.17 Similarly, a multicenter, placebo-controlled trial indicated that chlorpheniramine decreased nasal discharge, sneezing, and nose blowing and lessened the duration of cold symptoms.18 These benefits may result from the anticholinergic effects of first-generation antihistamines, specifically decreased nasal secretions.

There are few well-designed studies of antihistamine use in children with colds. One such study found that an antihistamine/ decongestant combination did not decrease the incidence of acute otitis media in children with URIs.19 A randomized, double-blind trial of an antihistamine/ decongestant combination (brompheniramine maleate and phenylpropanolamine hydrochloride) vs. placebo in children 6 months to 5 years of age with URIs showed no improvement in cough, rhinorrhea, or nasal congestion in the treated group but found that a larger proportion of the treated children, 46.6% vs. 26.5%, were asleep two hours after treatment. More than half of the children were better two days later regardless of whether they received drug treatment or placebo.12

Antitussives. Cough is often a major concern of parents, although the cough reflex is beneficial in that it clears excessive secretions and maintains airway patency. Cough suppression may be harmful in asthma, pertussis, and cystic fibrosis, allowing insipissation of mucous plugs, which can significantly worsen the patient's respiratory status.20

Narcotic cough syrups generally contain either codeine or hydrocodone, both of which are thought to act on the cough center in the brain stem. Even narcotics cannot completely suppress cough in adults. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, constipation, dizziness, and palpitations.20

Narcotic cough suppressants also may cause dose-related respiratory depression, which can lead to apnea and death. Codeine is conjugated by the liver, and the necessary hepatic pathways may not be fully developed in infants. Infants under 6 months of age appear to be particularly sensitive to the respiratory depressant effects of narcotics and may be at greater risk of apnea. Nalaxone can be used to reverse respiratory depression.

Dextromethorphan is a narcotic analog that suppresses cough in adults as effectively as codeine without CNS effects when used in appropriate doses. Overdosage, however, can depress respiration.20 A study in children between 18 months and 12 years of age reported no difference in cough reduction among groups receiving placebo, dextromethorphan, and codeine. Cough decreased in all patients after three days.21

Because no well-controlled studies exist documenting the efficacy of narcotics or dextromethorphan in treating cough in children and because these medications may have serious side effects, the American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends that pediatricians educate parents and patients about the lack of proven efficacy and risk of adverse effects of these products.20 Simple soothers such as tea, hard candy, cough drops, or even chicken soup are probably harmless but are of unproven value.

Expectorants. Expectorants are a common ingredient in cough/cold preparations. Guaifenesin (glyceryl guaiacolate) is the most common agent in use and is supposed to help thin secretions. Unfortunately, controlled study of guaifenesin shows no change in volume or quality of sputum.22 When used by young adults with colds, guaifenesin did not change cough frequency, although patients did report a subjective decrease in sputum quantity and thickness.23 Many cough and cold preparations contain both a cough suppressant and an expectorant. If both performed as advertised, the result would be a patient with thinned secretions that she could not remove from her airway.

Zinc. Some studies in adults have suggested that early treatment with zinc gluconate lozenges can shorten a cold. The exact mechanism of action is unclear. In vitro, zinc inhibits replication of rhinovirus and may combine with the rhinovirus coat proteins in such a way as to prevent viral entry into the host cell.

Treatment seems most effective if begun within 24 hours of onset of symptoms and requires taking five or six one-lozenge doses per day. Many patients in one study found the zinc lozenges difficult to tolerate. Nausea and bad taste were common complaints.24 A similar study in children 6 to 16 years of age demonstrated no benefit from zinc therapy. Side effects were common and included bad taste, nausea, irritation of the oropharanyx, and diarrhea.25

Analgesics and antipyretics. Children and adults often use acetaminophen and ibuprofen to treat the fever and discomforts of colds. In one study in adults, both acetaminophen and ibuprofen suppressed the host's neutralizing antibody response.26 In this same study, acetaminophen and aspirin treatment showed a trend toward longer duration of viral shedding. There was no significant difference in viral shedding among those treated with aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or placebo. Further study is needed to better understand the clinical significance of these findings in children and adults.

Other therapies. A variety of other therapies, including echinacea and vitamin C, have been suggested to relieve cold symptoms. The benefits of such treatments have yet to be demonstrated conclusively in randomized controlled trials.

Humidified air. Given the lack of effective pharmacologic agents to treat cold symptoms in children, physicians often recommend heated humidified air for symptomatic relief. A study comparing the effects of inhaling cold, dry air and warm, moist air showed that cold, dry air may increase nasal congestion and rhinorrhea in certain individuals.27 A few European studies suggested that inhaling steam reduced nasal obstruction in adults with colds for up to a week after treatment. The investigators postulated that the heated, humidified air inhibited rhinovirus replication. Similar studies in the United States not only failed to show any benefit from inhaling steam, but reported longer duration of symptoms in patients treated with steam compared to those who were not.28 Moreover, steam inhalation has been shown to have no effect on shedding of rhinovirus.29 Thus, air inhalation therapies provide no demonstrable relief.

Menthol vapor has long been thought to relieve nasal congestion and is often added to inhalation treatments. An objective evaluation of nasal resistance using rhinometry before and after menthol inhalation showed no consistent effect, but most patients reported subjective improvement in nasal airflow.30 Although menthol has no decongestant effects, it can cause an increased sensation of nasal airflow. Menthol may result in chemical irritation or burns when applied topically. If ingested in excess, it may cause nausea, vomiting, ataxia, and coma.

Ipratropium bromide is an anticholinergic nasal spray that effectively decreases the nasal discharge associated with the common cold. It is licensed for use only in children 5 years of age and older. Side effects, including excessive dryness of the nose and throat, nosebleeds, and headache, limit its usefulness.

Bulb suction and saline drops. Bulb suction remains a mainstay of therapy for infants with cold symptoms who cannot yet blow their noses. The effectiveness of suctioning as a kind of reverse nose blowing is often improved by using saline nose drops to humidify and loosen the nasal mucus. Saline drops are available over the counter, but parents can also make their own by mixing just under a teaspoon of salt in two cups of water.

Antibiotics. As one would predict based on the viral etiology of the common cold, antibiotics have no effect on the clinical course. They may be useful for treating bacterial otitis media and sinusitis, which sometimes accompany or follow a cold, and they have some effectiveness in preventing acute otitis media among otitis-prone children if given at the onset of a new cold. Antibiotics are not effective treatment for children with uncomplicated colds, and their indiscriminate use for viral infections promotes the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Can colds be prevented?

In view of the limited effectiveness of therapeutic measures for the common cold, are there any preventive measures that can be recommended? Children who are breastfed tend to have fewer colds than children who are bottle fed, so this constitutes yet another reason to recommend breastfeeding to expectant and newly delivered mothers.

In theory, frequent handwashing can reduce transmission of colds, and on the bright side, many children enjoy playing with water. Even physicians are often poor handwashers, however, and may fail to wash after each patient contact, so the practical value of suggesting frequent handwashing for young children is limited.

Immunization is moderately effective in preventing influenza, and vaccines against RSV are in development. Since there are more than 100 rhinovirus serotypes, however, a vaccine to protect against the most common causative agent would be hard to develop. A monoclonal antibody against RSV and RSV immune globulin have been shown to have limited efficacy in preventing RSV infections severe enough to require hospitalization of high-risk infants, such as premature infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. The high cost of these agents makes them impractical for general use, however.

The best prescription: Patience

Despite the desires of patients, parents, and physicians, there is no effective pharmacologic treatment of the common cold or its symptoms in children at the present time. Neither decongestants, antihistamines, cough preparations, expectorants, nor zinc lozenges have been shown to have any benefit in children, and they may carry substantial risks of side effects. Even routine symptomatic therapies such as antipyretics and humidified air may be counterproductive.

Since some studies in adults have demonstrated modest clinical value of OTC cough-and-cold medications, it was hoped that similar benefits could be expected in children. Controlled clinical studies in children, however, have generally shown limited or no benefit. In keeping with the scientific adage that "absence of proof is not proof of absence," it remains possible that some therapeutic benefits exist in children that have not yet been demonstrated. It seems likely, however, that the magnitude of any such hypothesized benefit must be small.

So the best medicine for treating colds in children is education. Parents need to understand the duration and expected symptoms of the common cold and know what specific changes in symptoms or duration would warrant a re-evaluation by their child's physician (see the parent guide, "Colds and your child"). They should be educated about the lack of proven efficacy of the available cold remedies and the side effects associated with their use (see "Talking with parents about cough and cold medications").

Colds and your child

A cold is a viral infection that can cause fever, headache, tiredness, fussiness, stuffy nose, runny nose, sneezing, sore throat, and cough. The drainage from the runny nose may be clear, yellow, or green. Preschool children get six to 10 colds each year. Most colds last 10 to 14 days in children. Antibiotics, such as penicillin, do not work against cold viruses.

Children get colds from other people who have colds. Colds are not caused by cold air, getting wet, or going outdoors without a coat or hat.

When your child has a cold, you should keep her as comfortable as possible. Be sure that she gets plenty of fluids to drink. You can use acetaminophen (for children over 2 months of age) or ibuprofen (for children 6 months of age and older) to treat bothersome fever or pain. Giving saline (salt water) nose drops and removing mucus with a bulb suction device may help clear infants' noses. Saline nose spray may relieve stuffy nose in older children.

Cough and cold medications will not make your child feel better, improve her symptoms, or make her cold go away faster. These medications can cause serious side effects in infants and children, as shown in the following chart.

Call the doctor if:

Your child is breathing harder or faster than usual.

Your child is wheezing or has noisy breathing.

Your child is not making as many wet diapers or urinating as often as usual.

Your child is extremely fussy.

Your child is very sleepy or inactive.

Your child has a rash.

Your child's cold lasts 10 days or more.

Your child has an earache.

Your child is younger than 2 months of age.

You have any other concerns about your child's illness.

If parents feel compelled to treat their child's symptoms, encourage them to use single-ingredient preparations designed to target the most problematic symptoms. Judicious use of antipyretics for fever, plenty of fluids, and saline nose drops may provide some symptomatic relief, but tincture of time is the only known cure.

REFERENCES

1. Hendley JO: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of the common cold. Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases 1998;9:50

2. Hendley JO: Rhinovirus colds: Immunology and pathogenesis. Eur J Respir Dis 1983;64(suppl 128):340

3. Pederson M, Sakadura Y, Winther B, et al: Nasal mucociliary transport, number of ciliated cells, and beating pattern in naturally acquired common colds. Eur J Respir Dis 1983;64(suppl 128):355

4. Gwaltney Jr JM, Phillips CD, Miller RD, et al: Computed tomographic study of the common cold. N Engl J Med 1994;330:25

5. Wald ER: Sinusitis in children. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:319

6. Gwaltney JM, Moskalski PB, Hendley JO: Hand-to-hand transmission of rhinovirus colds. Ann Intern Med 1978;88:463

7. Heikkinen T, Thint M, Chonmaitree T: Prevalence of various respiratory viruses in the middle ear during acute otitis media. N Engl J Med 1999;340:260

8. Osler W: Quoted in Pediatrics 1997;100:862

9. Smith MB, Feldman W: Over-the-counter cold medications: A critical review of clinical trials between 1950 and 1991. JAMA 1993;269:2258

10. Kogan JD, Pappas G, Yu S, et al: Over-the-counter medication use among US preschool-age children. JAMA 1994;272:1025

11. Kanfer I, Dowse R, Vuma V: Pharmacokinetics of oral decongestants. Pharmacotherapy 1993;13(6 pt2):116

12. Clemens CJ, Taylor JA, Almquist JR, et al: In an antihistamine-decongestant combination effective in temporarily relieving symptoms of the common cold in preschool children? J Pediatr 1993;130:463

13. Chin C, Choy M: Cardiomyopathy induced by phenylpropanolamine. J Pediatr 1993;123:825

14. Simons FE, Simons KJ: The pharmacology and use of H1-receptor antagonist drugs. N Engl J Med 1994; 330:1663

15. Fireman P: Pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy of common upper respiratory diseases. Pharmacotherapy 1993;13(6 pt2):1015

16. Doyle WJ, McBride JP, Skoner DP, et al: A double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of the effect of chlorpheniramine on the response of the nasal airway, middle ear, and Eustachian tube to provocative rhinovirus challenge. Pediatr Infect Dis J 1988;7:214

17. Crutcher JE, Kantner TR, Lilienfield LS, et al: The effectiveness of antihistamines in the common cold. J Clin Pharmacol 1981;21:9

18. Howard JC, Kantner TR, Lilienfield LS, et al: Effectiveness of antihistamines in the symptomatic management of the common cold. JAMA 1979;242:2414

19. Randall JE, Hendley JO: A decongestant-antihistamine mixture in the prevention of otitis media in children with colds. Pediatrics 1979;63:483

20. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Drugs: Use of codeine- and dextromethorphan-containing cough remedies in children. Pediatrics 1997;99:918

21. Hendeles L: Efficacy and safety of antihistamines and expectorants in nonprescription cough and cold preparations. Pharmacotherapy 1993;13(2):154

22. Taylor JA, Novack AH, Almquist JR, et al: Efficacy of cough suppressants in children. J Pediatr 1993;122:799

23. Kuhn JJ, Hendley JO, Adams KF, et al: Antitussive effect of guaifenesin in young adults with natural colds: Objective and subjective assessment. Chest 1982; 82:713

24. Mossad SB, Macknin ML, Mendendorp SV, et al: Zinc gluconate lozenges for treating the common cold: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Intern Med 1996;125(2):81

25. Macknin ML, Piedmonte M, Calendine C, et al: Zinc gluconate lozenges for treating the common cold in children: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1998; 279:1962

26. Graham NMH, Burrell CJ, et al: Adverse effects of aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen on immune function, viral shedding, and clinical status in rhinovirus-infected volunteers. J Infect Dis 1990;162:1277

27. Togias AG, Naclerio RM, Proud D, et al: Nasal challenge with cold, dry air results in release of inflammatory mediators: Possible mast cell involvement. J Clin Invest 1985;76:1375

28. Forstall GJ, Macknin ML, Yen-Lieberman BR, et al: Effect of inhaling heated vapor on symptoms of the common cold. JAMA 1994;271:1109

29. Hendley JO, Abbott RD, Beasley PP, et al: Effect of hot humidified air on experimental rhinovirus infection. JAMA 1994;271:1112

30. Eccles R, Jones AS: The effect of menthol on nasal resistance to air flow. J Laryngol Otol 1983;97:705

DR. PAPPAS is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at The University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

DR. HAYDEN is Professor of Pediatrics and Head of General Pediatrics at The University of Virginia. He has served as consultant for Merck, Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, and Wyeth-Lederle and as a speaker for Merck, SmithKline Beecham, and Wyeth-Lederle.

DR. HENDLEY is Professor of Pediatrics at The University of Virginia. He is a founder and corporate officer of Rhinotech, maker of a virucidal hand lotion, and Cold Cure, maker of antiviral/antimediator drugs for colds. He holds a patent on a virucidal hand lotion (not currently on the market).

ACCREDITATION

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Jefferson Medical College and Medical Economics, Inc.

Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, as a member of the Consortium for Academic Continuing Medical Education, is accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education to sponsor continuing medical education for physicians. All faculty/authors participating in continuing medical education activities sponsored by Jefferson Medical College are expected to disclose to the activity audience any real or apparent conflict(s) of interest related to the content of their article(s). Full disclosure of these relationships, if any, appears with the author affiliations on page 1 of the article.

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION CREDIT

This CME activity is designed for practicing pediatricians and other health-care professionals as a review of the latest information in the field. Its goal is to increase participants' ability to prevent, diagnose, and treat important pediatric problems.

Jefferson Medical College designates this continuing medical educational activity for a maximum of one hour of Category 1 credit towards the Physician's Recognition Award (PRA) of the American Medical Association. Each physician should claim only those hours of credit that he/she actually spent in the educational activity.

This credit is available for the period of December 15, 1999, to December 15, 2000. Forms received after December 15, 2000, cannot be processed.

Although forms will be processed when received, certificates for CME credits will be issued every four months, in March, July, and November. Interim requests for certificates can be made by contacting the Jefferson Office of Continuing Medical Education at 215-955-6992.

HOW TO APPLY FOR CME CREDIT

1. Each CME article is prefaced by learning objectives for participants to use to determine if the article relates to their individual learning needs.

2. Read the article carefully, paying particular attention to the tables and other illustrative materials.

3. Complete the CME Registration and Evaluation Form below. Type or print your full name and address in the space provided, and provide an evaluation of the activity as requested. In order for the form to be processed, all information must be complete and legible.

4. Send the completed form, with $20 payment if required (see Payment, next page), to: Office of Continuing Medical Education/JMC Jefferson Alumni Hall 1020 Locust Street, Suite M32 Philadelphia, PA 19107-6799

5. Be sure to mail the Registration and Evaluation Form on or before December 15, 2000. After that date, this article will no longer be designated for credit and forms cannot be processed.

FACULTY DISCLOSURES

Jefferson Medical College, in accordance with accreditation requirements, asks the authors of CME articles to disclose any affiliations or financial interests they may have in any organization that may have an interest in any part of their article. The following information was received from the authors of "Diagnosing and managing brain tumors: The pediatrician's role."

Diane E. Pappas, MD, JD, has no information to disclose

Gregory F. Hayden, MD, has served as a consultant for Merck, Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, and Wyeth-Lederle and as a speaker for Merck, SmithKline Beecham, and Wyeth-Lederle.

J. Owen Hendley, MD, is a founder and corporate officer of Rhinotech, maker of a virucidal hand lotion, and Cold Cure, maker of antiviral/antimediator drugs for colds. He holds a patent on a virucidal hand lotion (not currently on the market).

Diane Pappas,Gregory Hayden,J. Owen Hendley. Treating colds: Keep it simple. Contemporary Pediatrics 1999;12:108.