When pediatric hospitalists make sense

Some pediatricians consider hospitalists a threat to their professional scope and to continuity of care for their patients. But when conditions are right, hospitalists can be just what the doctor ordered.

When pediatric hospitalists make sense

By Fred J. Heldrich, MD

Some pediatricians consider hospitalists a threat to theirprofessional scope and to continuity of care for their patients. But whenconditions are right, hospitalists can be just what the doctor ordered.

In 1933, a new specialist was born--the board-certified pediatrician.Although the leadership of the American Medical Association only reluctantlyacknowledged that children were not small adults and warranted a separatespecialty, this attitude has changed. During the past several decades, pediatricsubspecialists, including neonatologists and pediatric intensivists, alsohave emerged to enhance the care of children. In addition, pediatric nursepractitioners provide both ambulatory care and hospital care to pediatricpatients.

Most recently, the pediatric hospitalist has appeared on the health-carescene, and some general pediatricians are worried. Will this new specialistprevent pediatricians from caring for their hospitalized patients? Pediatriciansspend three or more years in residency training and pass a board examinationand a recertification examination every seven years to remain accredited;they feel well-qualified to care for the patients they hospitalize. Whyshould they welcome pediatric hospitalists?

To answer these questions, we must consider the advantages and disadvantagesof hospitalists to hospitals, physicians, and patients, what a pediatrichospitalist does, and under what conditions the hospitalist can benefitboth pediatrician and patient. My view of these matters is based on 15 yearsof caring for my hospitalized patients in a community with one acute carehospital and no resident staff, followed by 30 years as hospitalist anddirector of a pediatric residency program in a community hospital in a largeurban center.

Issues for the general pediatrician

Although we don't think of pediatric subspecialists as hospitalists,many of them are, in that their practice is limited to hospitalized patients.Pediatricians who provide care to patients in pediatric emergency roomsor who are intensivists in pediatric intensive care units, for example,are hospitalists, as are neonatologists. General pediatricians recognizeand warmly receive these physicians' contributions to care of patients admittedto hospitals. Some feel differently about the hospitalist whose primaryresponsibility is to care for patients admitted to conventional pediatricwards, however.

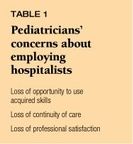

This type of hospitalist is not new to pediatrics either, though theterm "hospitalist" is. For many years community hospitals thataccept pediatric patients but do not have pediatric residents have employedboard-qualified or certified pediatricians as house officers. These physiciansprovide the same type of care as pediatric residents do for patients admittedto the services of private pediatricians. Nonetheless, some general pediatriciansworry that the hospitalist encroaches on an area of pediatric care in whichthey remain proficient and capable. They object to being unable to continueto use their skills and being denied the enjoyment and satisfaction of doingso. Some are also concerned about disrupting continuity of care, which isbest provided by a physician who has an intimate knowledge of the patient'smedical history and socioeconomic situation. Table 1 summarizes these concerns.Althoughmost general pediatricians do not complain about loss of income resultingfrom time away from the office, some do support the employment of hospitalistsbecause of the expected boost to pediatricians' incomes.

Pediatricians who prefer to care for their own hospitalized patientsshould consider whether they can provide the same quality of care as a hospitalistcan. In many instances they can, but in an emergency they may fall short.How well the pediatrician can meet two requirements for hospital care--abilityand availability--makes the determination.

Ability. The physician must have well-honed technical skills; skillsthat are used infrequently often are lost. Proficiency in obtaining arterialor venous access and performing lumbar punctures and endotrachial intubation,and an ability to perform and direct cardiopulmonary resuscitation, aremandatory. Performance of thoracentesis, bone marrow aspiration, and exchangetransfusion may be required, as may interpretation of electrocardiogramsand chest radiographs. These skills become even more critical when intensivistsor subspecialists are not available to provide support or the hospital hasno resident staff.

Availability. The availability of the practicing pediatrician is criticallyimportant and highly dependent on how far the hospital is from the homeand office. Pediatricians who are members of a group practice can circumventthis problem by assigning one member of the group to serve as hospitalistfor the day for the entire group. In assessing availability, a pediatricianmust consider how much time needs to be allotted to care for hospitalizedpatients.

An inadequacy in either of these prerequisites, summarized in Table 2,compromises a pediatrician's ability to care for hospitalized patients andlends support for recruiting pediatric hospitalists.

One hospital's experience

An account of why one community decided to employ pediatric hospitalistsand how it uses them will illuminate these issues. Two graduates of ourpediatric residency program joined a senior pediatrician practicing in asmall town 35 miles from an urban center. The community hospital had 10pediatric beds. The pediatricians had the requisite ability and, initially,availability. They were quite capable of caring for patients they admittedto the hospital, and they triaged those who required tertiary care to urbanmedical centers. Since they were just establishing their practice, theyhad ample time to provide full coverage to their hospitalized patients aswell as attend high-risk deliveries and act as consultants in the emergencyroom.

As the practice grew, however, time for hospital calls shrank. The pediatriciansenlisted the support of other physicians and the hospital administratorsto employ pediatric hospitalists, who would be available to give hospitalizedpatients attention at all times.

The newly hired hospitalists were four pediatricians who had recentlycompleted their residencies. They admitted and cared for patients who didnot have private pediatricians with attending privileges or who were referredby community physicians. They cared for sick newborns, attended Caesareansections and other high-risk deliveries, and served as pediatric consultantsto emergency room physicians. The private pediatricians retained privilegesto admit and care for their patients if they chose to do so; the hospitalistsassisted them as requested or required. The hospitalists were expected torespond to any emergency situation for any patient at any time.

The relationship between the hospitalists and the private pediatricianswas, and still is, cooperative and collegial. Billing is not a problem sincethe hospitalists are salaried, and the hospital sends out bills for servicesthey render. Private physicians send their own bills for services they provide.The hospital is supportive and maintains an excellent pediatric unit. Asa result, the quality of care is high and children in this town who requirehospitalization generally don't need to be sent elsewhere.

What does a hospitalist do?

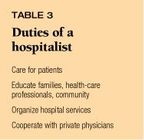

Hospitalists primarily take care of patients, but may have other duties,listed in Table 3, as well.

Patient care. Hospitalists are responsible for caring for patients admittedto their service but are also available to assist with patients admittedby physicians on the attending staff. Their ability to cooperate with theattending staff who use the hospital's pediatric services is critical totheir acceptance. Hospitalists should not only respond to formal requestsfor assistance but monitor the progress of patients of the private staffwhen the attendings are not in the hospital. This might entail explainingto patients or parents the diagnosis and treatment plan the private attendinghas outlined, answering parents' or patients' questions, and notifying theprivate attending about any questions or concerns that the parents or patienthave. Hospitalists should promptly inform private physicians of laboratoryresults or significant changes in their patients' conditions.

Education and organization. Hospitalists have the opportunity to helpdevelop continuing education programs for physicians. Because they workfull time in the hospital, they have ready access to the library to researchmaterial for conferences and provide up-to-date information. Educationalresponsibilities could include leading sessions for medical assistants,therapists, and nursing staff. Hospitalists may also help develop communityprograms on medical subjects.

Other activities might include organizing CPR procedures or other servicesto optimize patient care and participating in development of practice guidelines.

When will it work?

Hospitalists are not appropriate for every community. They are most likelyto be effective under conditions like those shown in Table 4.

Private pediatricians and hospital want to hire hospitalists. Employmentof hospitalists should be a joint decision by the hospital administrationand the physicians in the community. Pediatricians may have no desire forhospitalists until careful consideration reveals their advantages to thecommunity, the hospital, and the physicians.

Pediatricians retain admitting privileges. Even when there are hospitalistson staff, some pediatricians prefer to admit patients to their private serviceand care for them. Hospitals should respect this choice and make it available.In return, private attendings must be prepared to provide excellent careand supervise their patients at all times, designating another qualifiedphysician to substitute in their absence. The hospitalist would be an excellentchoice in this situation.

Hospitalists don't invade pediatricians' turf. For a good working relationship,hospitalists should avoid competing with private physicians in the community.They should not be in private practice themselves and must be careful tosend patients back to their private physicians after discharge from thehospital.

Although it is best for a hospital to employ a full-time hospitalist,such an arrangement may not always be practical, particularly in small communities.It may instead be appropriate to hire qualified pediatricians who practicein the community to work part time as hospitalists. These part-timers alsoshould send patients back to their private physicians when they are dischargedfrom the hospital.

Hospital provides support services and flexibility. The hospital oughtto cast the deciding vote about recruiting a hospitalist because the hospitalistis the hospital's employee. The hospital should have a pediatric unit of10 or more beds and be prepared to provide support services and essentialequipment. The presence of qualified hospitalists may encourage physiciansto admit their sicker patients to that institution, increasing the numberof its pediatric patients. Revenue derived from hospitalists' services andresulting from tests, procedures, and medications the hospitalists orderwill compensate for their salaries.

Some observers claim hospitalists shorten lengths of stay and reducethe cost of medical care. Although these are important issues, they shouldnot be major reasons for employing hospitalists.

Potential problems

Of course, the climate for using hospitalists is sometimes less thanideal. Common problems include hospitals that do not allow community pediatriciansto care for their patients, misunderstandings and conflicts about how dutiesare allocated between the private physician and the hospitalist, and nothaving enough hospitalists or hospital support.

Hospital prohibitions. Unfortunately, some hospitals do not allow communitypediatricians to admit and care for their patients, even when they are qualifiedto do so. In certain hospitals owned and operated by health maintenanceorganizations (HMOs), the HMO hires hospitalists to care for the patientsof physicians in the HMO--and only those patients. In what is probably notan isolated incident, an HMO in Maryland recently made an abortive attemptto prevent private physicians in their group from managing their hospitalizedpatients. Doctors who anticipate joining managed care organizations shouldbe aware of any limitations these groups may place on their practice options.

Unclear division of responsibilities. Most hospitals that employ hospitalistshave three options for admitting patients to the pediatric ward: to thehospitalist, to the private attending, or to the private attending withthe understanding that the hospitalist will assume certain responsibilitiesthat have been mutually agreed on. The physician may request a formal consultationwith the hospitalist or limit the hospitalist's assistance to specific tasksor procedures. Written orders clarifying these shared responsibilities eraseany uncertainties the nursing staff has about each physician's responsibilities.

The private pediatrician or hospitalist must fulfill eight major responsibilitiesor duties for each patient admitted to a pediatric floor (Table 5). Theprivate attending assumes full responsibility for these activities for thepatient who is admitted to the pediatrician's service; the hospitalist assumesresponsibility for the patient admitted to the hospitalist's service. Itoften is best for private attendings and hospitalists to share these responsibilitiesfor a patient who administratively remains on the private physician's service,as shown in the table. This is especially true for pediatric patients admittedto the surgical service. In hospitals where pediatricians and hospitalistsrespect and appreciate each other's roles in patient care, the two partiescan cooperate without resorting to written orders. To avert questions fromconfused patients and parents, however, the pediatrician should explainthe role of the hospitalist when the patient is admitted.

Inadequate staffing and assistance. Since hospitalists' services shouldbe available at all times, one hospitalist on a staff is not enough. Whenthere is only one, qualified physicians such as fellows in pediatric trainingprograms or practicing pediatricians in the community may be used part timeto augment the hospitalist's services. Recent graduates of residency programsare excellent choices for these positions since the daily activities ofsenior residents are similar to those of hospitalists.

Making the decision

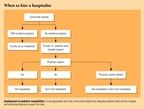

In determining the feasibility of recruiting a hospitalist, cooperationbetween local pediatricians and the hospital administration is critical.Ideally, as shown in the algorithm below, a hospitalist is recruited whenphysicians support the idea, the hospital has at least 10 pediatric beds,and the hospital administration is receptive to the proposal. At communityhospitals with residency programs, faculty members can act as hospitalistsby assisting and supervising residents; the faculty members must be availableat all times.

When the number of pediatric beds is adequate and the hospital favorsemploying a hospitalist but the private attending staff is divided, thehospital may go either way. If it decides to hire hospitalists, the moveis likely to be successful. Physicians opposed to the idea probably willbe won over when they realize that by cooperating with the hospitaliststhey can enhance patient care. This is what happened when neonatologistsfirst appeared on the scene, as the box on the right describes. If the hospitaldecides not to hire hospitalists because some physicians object, privatepediatricians must remain available to their hospitalized patients at alltimes. In addition, not having hospitalists will affect the number and typeof patients the hospital admits; some patients will need to be sent to otherhospitals to obtain the care and supervision they need.

Summing it up

Of the many factors that frame the current debate about the role of pediatrichospitalists in community hospitals, four stand out:

- Hospitalists can contribute significantly to the care of hospitalized children in many community hospitals that currently don't use them.

- Hospitals and community pediatricians must jointly make the decision whether or not to employ hospitalists, making the welfare of hospitalized children the primary concern.

- Private pediatricians should retain the privilege to admit and care for their patients in accordance with their admitting privileges in hospitals that use the services of hospitalists.

- The general pediatrician and pediatric hospitalist can co-exist in harmony.

THE AUTHOR is Associate Professor, Pediatrics, Johns Hopkins UniversitySchool of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

Having "the talk" with teen patients

June 17th 2022A visit with a pediatric clinician is an ideal time to ensure that a teenager knows the correct information, has the opportunity to make certain contraceptive choices, and instill the knowledge that the pediatric office is a safe place to come for help.

Artificial intelligence improves congenital heart defect detection on prenatal ultrasounds

January 31st 2025AI-assisted software improves clinicians' detection of congenital heart defects in prenatal ultrasounds, enhancing accuracy, confidence, and speed, according to a study presented at SMFM's Annual Pregnancy Meeting.