Croup in the COVID-19 era

The pandemic has increased awareness for many infectious diseases, including croup.

Cough is one of the most common complaints brought to the pediatric practice, resulting in nearly 30 million outpatient visits each year.1 Although many cases of cough involve the upper airway and are caused by viruses, they are not all the same in terms of severity.

Upper airway obstruction—caused by inflammation and swelling in the larynx, trachea, and bronchi—creates a loud “barking” cough that is a tell-tale sign of croup. Although the management of many diseases has evolved over the years, not much has changed when it comes to croup. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased awareness—and paranoia—surrounding respiratory infections.

Here is the latest guidance for managing croup, and how to differentiate this condition from other respiratory illnesses.

What is croup?

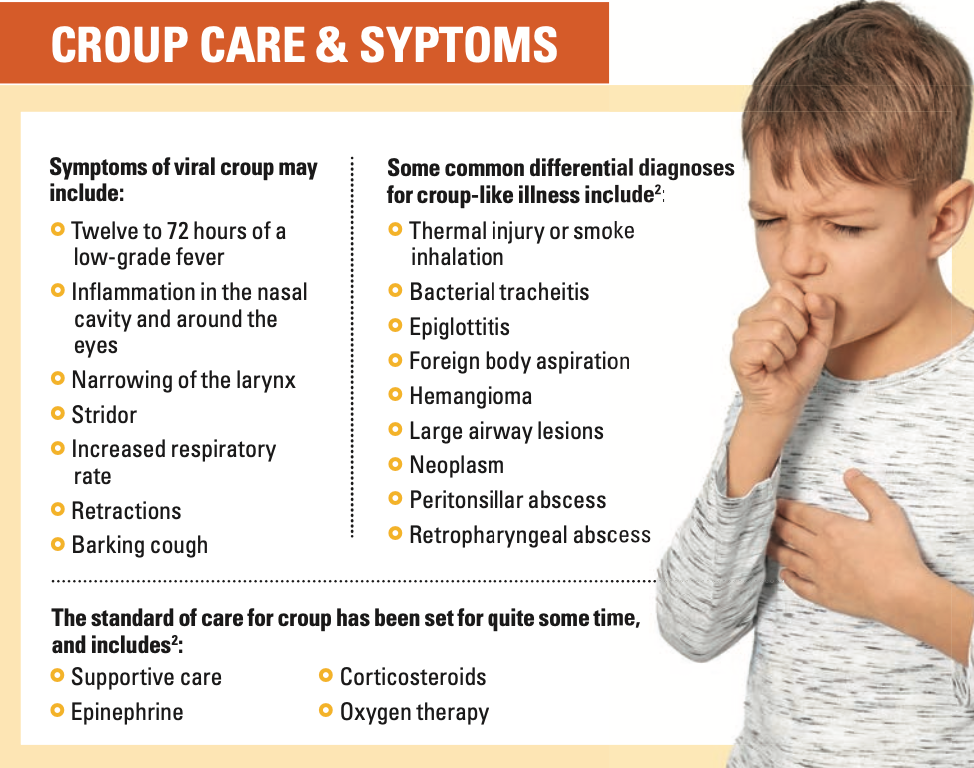

Croup is a respiratory condition based on clinical findings, such as hoarseness, a barking cough, or stridor. The condition is most common in the fall and winter, and viruses are to blame for 80% of cases.2 The most common viral causes of croup are2:

- Parainfluenza virus 1

- Parainfluenza virus 2 and 3

- Influenza A

- Influenza B

- Adenovirus

- Respiratory syncytial virus

- Rhinovirus

- Enterovirus

Less often, bacterial infections like Mycoplasma pneumonia and Corynebacterium diphtheria may also result in croup.

Most cases (85%) are mild, but about 1% end up severe. In severe cases, croup can lead to stridor and hypoxia. Up to 5% of all children with severe croup may end up hospitalized, but only between 1% and 3% ever require intubation.2

Symptoms often get worse at night, especially when a child is emotionally distressed by their symptoms. The illness usually peaks in 24 to 48 hours, resolving in about a week, in most cases.2

Making a diagnosis

The sudden onset and loud nature of a croup cough can be concerning, especially now, when concern for COVID-19 variants are at an all-time high. However, there’s no definitive test to diagnose croup. Croup is mostly diagnosed by clinical symptoms, although infection with a particular virus or bacteria can be confirmed with lab testing.

In most cases, however, it’s less a matter of what is causing that croup than how bad of a case it is, says Mike Patrick, MD, an emergency medicine and general practice pediatrician at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. Patrick has covered croup and several other issues in his podcast, PediaCast, a pediatric podcast for parents.

The first step in diagnosing croup is to assess the child’s symptoms and determine how severely the croup has presented, he says. The increased use of telehealth since the COVID-19 pandemic can help in this regard, since it’s now easier than ever for pediatricians to connect visually with their patients who are at home.

If it’s a patient you know, Patrick suggests making a judgment on their individual health history and reports from caregivers. Children who present simply with hoarseness or a barking cough can usually be managed at home, but those who experience stridor or difficulty breathing should be seen immediately in an urgent care center or emergency department, in most cases.

Management and treatment

Supportive care is the hallmark of croup treatment and is the primary treatment at home, in most cases. For years, the advice has been to use humidified air to help manage the symptoms of croup, says Patrick, but recent research hasn’t been able to prove that this works.

“A lot of times, kids sound bad at home, and by the time they get to the emergency department, they sound better because they were out in the cool night air,” Patrick says. “That’s traditionally what people have been told to do for croup, but the most recent studies would suggest that humidified air doesn’t do as much as we hoped it would do.”

Still, if it helps caregivers and children feel better, or like something is being done, it doesn’t hurt, he adds.

Other supportive care methods that can help manage symptoms include emotional support, adequate hydration, and treatment of pain or fever with things like acetaminophen.

Croup care and symptoms

For some children, supportive care is enough, but clinical guidelines also support the use of oral corticosteroids in any child with croup, regardless of severity.2 Patrick says children typically receive a 1-time dose of dexamethasone orally (0.15-0.6 mg/ kg)2 if they have a severe cough or intermittent stridor with their croup. Some facilities may also choose to use an intravenous formulation.

This 1-time dose will work for a few days in the body to help reduce inflammation, but some children will have to return for additional doses days after they were first seen, Patrick says.

When a child presents with severe croup—featuring constant stridor, shortness of breath, or other signs of hypoxia—or if oral corticosteroids haven’t provided any relief, the next step is to administer aerosolized epinephrine. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) suggests the following doses2:

- Up to 0.5 mL of 2.25% racemic epinephrine

- Up to 5 mL of L-epinephrine 1:1000

With this treatment, it’s important to remember that as the treatment wears off, inflammation can return and be more severe. If it is administered in an outpatient setting—or even in an urgent care center or emergency department—the child should be monitored for at least a few hours for a rebound reaction, or to see if another dose is needed, Patrick explains.

If another dose is required, chances are the child should be admit- ted for at least an overnight stay in the hospital anyway, he adds. AAFP recommends monitoring children who received epinephrine breathing treatments for at least 4 hours.2

Considerations with COVID-19

There are many concerns about respiratory symptoms as the COVID-19 pandemic continues to evolve. The emergence of new variants continues to present challenges in bringing the virus under control, as well as in properly diagnosing other respiratory illnesses.

Patrick says his organization is not universally testing all children for COVID-19 when they present with respiratory symptoms. Instead, testing is done when it is warranted by the situation. For example, if a child will be staying home with vaccinated parents as they recover, testing would not impact treatment and may not be necessary. When children need to return to a school or day care environment, testing may be required more for isolation purposes than anything else, he says.

There have been some cases noted where COVID-19 and croup have occurred together,3 but Patrick says this isn’t all that surprising.

“If they are positive [for COVID-19], kids can have multiple viruses going at once. Whether COVID-19 is with croup or other viruses isn’t the issue,” Patrick says. “Which virus is less important than addressing the case based on croup severity.”

Perhaps what is more important than what virus is causing croup symptoms, is what other illnesses or conditions the child may have. Certain groups are at a higher risk in terms of both COVID-19 and croup, he says. This group mostly includes children who are immunocompromised either from immune disorders or medications, such as chemotherapy. Interestingly, Patrick says there doesn’t appear to be much of an association between children with asthma and COVID-19 severity, but children who already have breathing problems may require special attention when it comes to croup.

Regarding croup and high-risk children, Patrick says that he tries to get a sense of how severe their symptoms are before making a recommendation on where to receive care.

“You don’t want to miss the kid who is getting worse, but you also don’t want to increase exposure,” he says.

Children who have a history of breathing problems or who are immunocompromised may be best served staying at home with mild croup symptoms, but a worsening clinical picture could outweigh any infectious disease risks that occur with emergency department or office-based care, Patrick says.

One way COVID-19 may be increasing the risk—at least anecdotally—is in increased respiratory illness overall, he adds. This may be more of a result of COVID-19 mitigation strategies, such as masking and social distancing, than the virus itself, he adds, pointing to a drop last year in influenza cases.

“It’s crazy how much cough we are seeing right now [in early August] in bronchiolitis,” Patrick says. “The pandemic in general has shifted epidemiology for viruses.”

Reduced exposure—especially in young children, over the past 18 months—may be limiting their natural immune defenses against respiratory viruses and making them more susceptible to infection as they interact with more people.

Recovery and prevention

Just as masking, social distancing, and hand hygiene have been used to try to prevent the spread of COVID-19—and potentially other respiratory diseases—croup may be avoided through the same strategies. Families should be encouraged to avoid areas where there are sick people in close quarters, to stay home if they are sick themselves, and to be vigilant with personal hygiene and hand washing when seasonal viruses are rampant.

Recovery from croup usually takes several weeks, and Patrick warns that parents and caregivers may need some reassurance. It’s not uncommon for a cough to last for several weeks after a viral illness, he says, and the key is that the cough gradually improves over time. If the cough worsens or lasts too long, clinicians may want to re-examine the child to rule out pneumonia or other differential diagnoses.

Although new research may be placing age-old remedies, such as steam, into doubt, when it comes to croup, there isn’t much that can hurt in terms of supportive care. The primary method for managing croup is to treat the child based on their clinical presentation. Hospitalization and medications, such as corticosteroids and epinephrine, may help in mild to severe cases, but treatment is largely based on symptom severity, not the source of infection, regardless of the fact that there is an ongoing respiratory virus pandemic.

Therefore, in most cases, caregiver reassurance and education on emergency symptoms is enough to manage croup.

References

1. Kasi AS, Kamerman-Kretzmer RJ. Cough. Pediatr Rev. 2019;40(4): 157-167. doi:10.1542/pir.2018-0116

2. Smith DK, McDermott AJ, Sullivan JF. Croup: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97(9):575-580.

3. Venn AMR, Schmidt JM, Mullan PC. Pediatric croup with COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;43:287.e1-287.e3. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.09.034

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.