Fall allergies: Medications remain stable, but a lot has changed

With COVID-19 still at large, pediatricians should prepare for a tough allergy season.

As variants of SARS-CoV-2 continue to emerge, much of the world has returned to some sense of normalcy. School bells are ringing, and children—some masked, some not—are back to in-person learning. All this begs the question “How will COVID-19 affect the fall allergy season, and are there any new tools in the pediatrician’s arsenal?”

Predictions for fall

Stanley M. Fineman, MD, a pediatric immunologist at Atlanta Allergy and Asthma in Georgia and a spokesperson for the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, says back-to-school season is always a struggle as kids come together and fall allergies and the cold and flu season meet.

“The kids last year were social distanced, and most were not in school or wearing masks, so the incidence of upper respiratory infections went way down,” Fineman said. Even some patients who normally had pollen- type allergies reported fewer symptoms, potentially also from masking, he added.

No one knows how bad the pollen season will be this fall, but children with severe respiratory allergies will be in the same boat they’ve always been in—at a higher risk of other respiratory infections, more asthma flare-ups, and increased hospitalizations.

“Those are serious concerns we have,” Fineman said. “We just have to be extra cautious and warn our patients. They need to know what their allergies are, and you should have a skin test if you are at risk.”

Skin tests are the best way to pinpoint allergens, Fineman said, and most allergists agree that knowing one’s triggers and following local pollen counts are essential to managing allergy flare-ups.

Rachel Dawkins, MD, medical director of the pediatric and adolescent medicine clinics at Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital in St Petersburg, Florida, agrees that it’s shaping up to be a more difficult fall allergy season than usual. “As pediatricians, we are expecting a very rough fall. Students are back in school in person and, in many cases, unmasked in the classroom,” Dawkins said. “On top of that, we are seeing outbreaks of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and COVID-19, as well as other viral illnesses. It is going to be tough to decide what is viral vs allergic in the office and how to decide who to send back to school and who to tell to quarantine.”

Dawkins encourages her patients with known seasonal allergies to restart their antihistamines as fall approaches rather than until they have symptoms.

“Especially in our younger or unvaccinated patients, they will likely need to be tested for COVID-19 if symptomatic prior to returning to school even if they have a history of seasonal allergies,” she said. “In areas like mine [Florida], where community testing sites have closed, the volume of sick children needing to be seen and tested will be a challenge.”

Allergies or COVID-19?

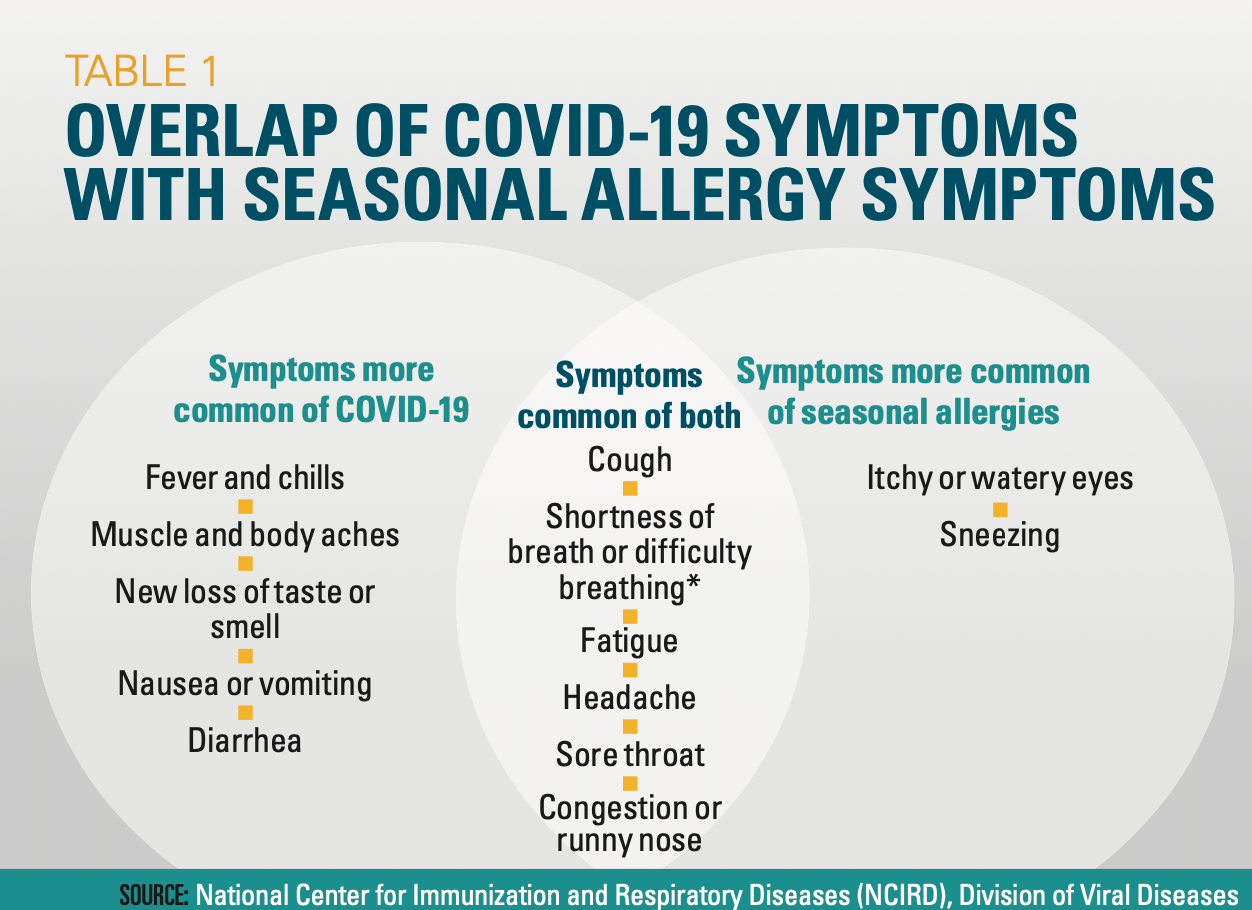

The biggest challenge in the upcoming allergy season may be trying to differentiate between respiratory allergy symptoms and infectious diseases like COVID-19.

“If there’s a family or personal history of allergies, then it’s possible it’s allergies,” Fineman said. “But in the school setting, if they have a fever, all bets are off.”

The presence of a fever is a major red flag in differentiating allergies from infections, he explained, adding that good assessment skills can help clinicians be judicious in testing for illnesses such as influenza and COVID-19.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had interesting effects in terms of allergies and other infectious diseases, according to Mitchell H. Grayson, MD, chief of the Division of Allergy and Immunology at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio. For example, a massive RSV season is under way, even though it’s not the normal season for the virus, he said: “RSV clearly has the ability to not stick to its seasonal barriers, but I wonder about influenza.”

Table

Masking has helped reduce the spread of respiratory viruses and maybe even some pollen, but building protection requires exposure. “We saw a dramatic decrease in kids’ exposure to allergens and exacerbations a year ago, presumably due to masking and not gathering,” Grayson said. “I’m guessing that masking in the fall would have similar results.”

Most areas began dropping mask mandates in the spring, which is when there was an increase in both allergic exacerbations and viral illnesses, he said. It makes sense that masking helps reduce the amount of pollen and other allergens that are taken into the body, but not much has changed in terms of indoor allergies. Many other factors could be coming into play, Grayson said, but masks seem to be the primary reason for the reduction of allergy, illness, and asthma problems last year. Fewer office visits could have played a role, but not to the extent that most areas saw, he said: “I find it hard to believe that people with asthma were having severe exacerbations and riding out at home [during the pandemic].”

Dawkins’ practice got ahead of the fall allergy season by creating a list of frequently asked questions for the call center and triage nurses. This guide will help staff keep caregivers updated on any recommendations from organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics, and local governments. “This way we have a united message for families,” Dawkins said.

Asymptomatic children who have been exposed to COVID-19 are referred to community testing sites, and Dawkins said her practice has decided not to write mask exemption letters and is encouraging all children who are able to get the vaccine.

Treatment strategies

There are no new medications on the horizon for seasonal relief, but Fineman noted that in recent years, there has been a greater push toward using inhaled nasal steroids as a first- line treatment for upper respiratory allergies. These should be initiated 3 to 4 weeks before the new allergy season begins.

For patients who prefer oral antihistamines, second-generation options are preferred. These medications, such as loratadine and cetirizine, are highly effective and rapid acting and don’t cross the blood-brain barrier, Fineman said. This means that, unlike medicines such as diphenhydramine, they don’t have the sedating effects on the central nervous system.

Currently, there is a lot of research into biologics and immunology trick- ling down from adult medicine to pediatric practice, Grayson said.

Fineman stressed the benefit of immunotherapy, especially in children with severe allergies. “We know that kids who have significant allergies are benefiting from allergen immunotherapy,” he said. Children with upper respiratory allergies may be predisposed to lower or reactive asthma, and immunotherapy can reduce that risk, Fineman explained.

Although pediatricians can man- age a lot in general practice, Fineman emphasized that children who experience severe allergies would be best served with a referral to an allergist and possibly immunotherapy to reduce symptoms and complications.

The Role of the Healthcare Provider Community in Increasing Public Awareness of RSV in All Infants

April 2nd 2022Scott Kober sits down with Dr. Joseph Domachowske, Professor of Pediatrics, Professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Director of the Global Maternal-Child and Pediatric Health Program at the SUNY Upstate Medical University.