Adolescent With Syncope-Or Something Else?

A 16-year-old boy presented for evaluation of asthma and exercise-induced bronchospasm. His parents recalled an episode 2 months earlier in which the patient, while jumping on a trampoline and wrestling with his brother, felt like he could not catch his breath. He took a puff of his rescue inhaler, and soon after, passed out. He remained unresponsive for 2 hours.

A 16-year-old boy presented for evaluation of asthma and exercise-induced bronchospasm. His parents recalled an episode 2 months earlier in which the patient, while jumping on a trampoline and wrestling with his brother, felt like he could not catch his breath. He took a puff of his rescue inhaler, and soon after, passed out. He remained unresponsive for 2 hours.

The teen had been taken to a hospital, where he was extensively evaluated for presumed syncope by the pediatric cardiology and pediatric neurology teams. The results of all studies and laboratory tests, including a toxicology screen, ECG, echocardiogram, electroencephalogram, and CT scan of the brain, were within normal limits. After 3 days, he was discharged. No cause of the syncopal episode had been identified. Results of an outpatient Holter monitor study and a tilt table test were normal.

Within the first 3 minutes of the time during which this history was obtained, the patient had fallen asleep (Photo). When asked later what he remembered from the episode of 2 months ago, the patient gave a slightly different story. He said he had been listening to a friend tell a joke when he started laughing and passed out. The patient denied use of caffeine, drugs, or cigarettes. He stated that he tires easily in school and that his grades have dropped.

His medical history consisted of mild intermittent asthma, allergies, tympanostomy with tube placement, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. He had had no cardiac problems or seizures. His medications included albuterol as needed and methylphenidate daily. His mother and brother had asthma and allergic disease, and his father had obstructive sleep apnea and narcolepsy. In fact, soon after the patient had fallen asleep, the father also fell asleep.

When examined, the patient appeared comfortable, alert, and cooperative. Height and weight were at the 50th percentile. He had narrow nasal passages with slight deviation of the nasal septum. Physical findings were otherwise normal.

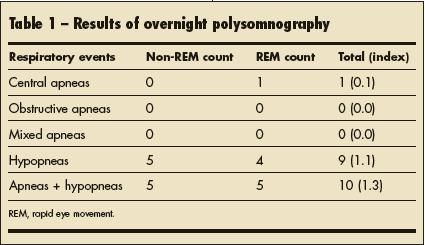

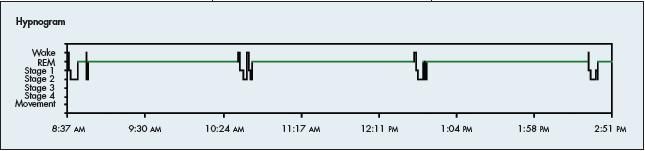

Results of office-based pulmonary function studies and a chest radiograph were normal. To investigate further, overnight polysomnography was performed the next evening followed by a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT). Human leukocyte antigen (HLA) typing for narcolepsy was also ordered. The polysomnogram indicated pathological sleepiness on the basis of the short amount of time that it took for the patient to lapse into rapid eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure 1, Table 1). The patient had 1 central apnea and 9 hypopneas; the apnea/ hypopnea index was 1.3 events per hour. This normal apnea/hypopnea index ruled out obstructive sleep apnea as the cause of his excessive daytime sleepiness.

Figure

Figure 1 – This hypnogram from the patient's overnight polysomnogram shows that sleep latency was short and that sleep was entered into at the rapid eye movement (REM) stage. Sleep latency was 1 minute, which indicates pathological sleepiness. REM latency was 6 minutes and 30 seconds, which indicates almost sleep-onset REM.

Table 1

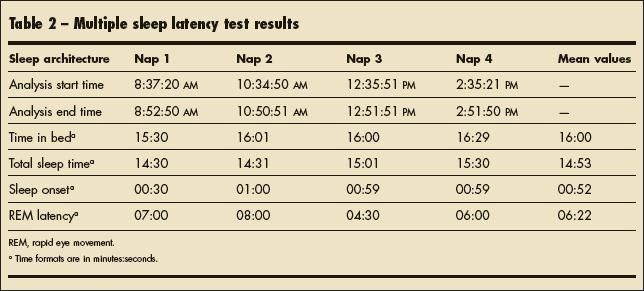

The MSLT showed that in all 4 naps, the patient slept and achieved REM sleep (Figure 2, Table 2). Mean sleep latency, or the average time it took the patient to fall asleep for all 4 naps, was 52 seconds. These study results, along with the patient's clinical presentation, were diagnostic for narcolepsy, even though the results of HLA typing for narcolepsy were negative.

Figure 2 – The hypnogram from the multiple sleep latency test shows that in all 4 naps, the patient slept and achieved rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The mean sleep latency was 52 seconds.

Table 2

APPARENT SYNCOPE: SORTING THROUGH THE DIFFERENTIAL

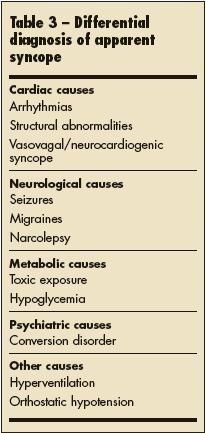

This patient's initial presentation of "passing out" is similar to what many think of as syncope. However, not all cases of sudden loss of consciousness and postural tone are syncope. It is important to consider all entities in the differential diagnosis of apparent syncope, which could include cardiac, neurological, metabolic, psychiatric, and other causes (Table 3).

Table 3

Cardiac causes. Life-threatening causes of syncope are generally cardiac in origin and must be considered first. These include arrhythmias (eg, long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, pre-excitation syndromes) and structural abnormalities, such as repaired congenital heart disease, aortic stenosis, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. 1 This patient did not have any known cardiac defects, and results of his cardiac evaluation were normal.

Noncardiac causes. The most common cause of syncope in children and adolescents is vasovagal or neurocardiogenic syncope, which represents about 50% of emergency department cases.2,3 Often patients may recognize precipitating physical or emotional triggers, as well as a prodrome of symptoms (dizziness, nausea, vision changes, sweating).4 Normal orthostatic blood pressures and a negative tilt table test pointed away from this common diagnosis in this patient. Other common causes of syncope in adolescents include orthostatic hypotension, toxic exposure, and hypoglycemia.

Syncope mimics. The following conditions may masquerade as syncope:

- Seizuresusually include loss of consciousness and postural tone; however, they also consist of a preceding aura and postictal phase.

- Migraines that present with loss of consciousness typically involve other neurological symptoms, such as headache and nausea.

- Conversion disorder often happens in front of an audience and usually occurs without injury. The patient may even be able to recall some of the event. This disorder is most common in adolescents.

- Hyperventilation is also common among adolescents; it often follows emotional stress. Loss of consciousness from this phenomenon is preceded by somatic complaints, such as chest pain or tightness, difficulty in breathing, dizziness, tingling sensation in the hands, and vision changes.1

- Narcolepsy is often forgotten in adolescents, despite its onset being most common during adolescence; in fact, 90% of persons with narcolepsy have symptoms before age 25 years.5 Classic findings include frequent (2 to 6) daily, irresistible sleep attacks, after which the patient feels refreshed. The attacks can occur in unusual situations, such as while standing, talking, or even driving. Cataplexy, a sudden loss of muscle tone brought on by intense emotion (eg, laughing) or physical activity, is seen in some patients. Episodes usually last only seconds to minutes, although they have been known to last hours (a phenomenon known as status cataplexicus). 6 We believe this patient was in a state of status cataplexicus during his 2-hour loss of consciousness.

NARCOLEPSY: AN OVERVIEW

Diagnosis. Although not a true cause of syncope, narcolepsy remains in the differential diagnosis and must be considered when other life-threatening and common causes of syncope have been ruled out. A phenomenon unique to narcolepsy is sleep-onset REM periods, or SOREMPs.7 Instead of progressing in a normal sleep pattern from non- REM sleep into REM sleep, persons with narcolepsy can fall directly into REM sleep. This can be documented, as seen in this patient, by overnight polysomnography and MSLT and is diagnostic for narcolepsy.

MSLT is done during the day after an overnight sleep study. The patient is given several opportunities to nap at 2-hour intervals in the hope of quantifying short-latency onset of REM sleep.

Nocturnal polysomnography that excludes other pathological sleep disorders (eg, obstructive sleep apnea) and MSLT that documents a mean sleep latency of less than 8 minutes, in addition to 2 or more SOREMPs, are considered the gold standard for diagnosing narcolepsy. In children, these results in conjunction with a clinical history of excessive daytime sleepiness with or without cataplexy, hypnagogic hallucinations, or sleep paralysis are used to make the diagnosis.6

HLA typing and measurement of hypocretin levels in the cerebrospinal fluid are other ways to diagnose narcolepsy; however, negative HLA studies do not exclude the diagnosis. We commonly see patients with a clinical diagnosis of narcolepsy who have negative HLA typing. Although evidence shows a familial predisposition to narcolepsy, there may also be a secondary autoimmune component.

Treatment and prognosis. Treatment of narcolepsy consists of a mixture of therapies, including scheduled naps, stimulant medications, and tricyclic antidepressants. When narcolepsy is suspected, refer the patient to a sleep specialist/neurologist. Narcolepsy is a serious lifelong condition.6

This disorder, which commonly begins in adolescence, can be psychosocially traumatic for a young person. More important, a patient's participation in common activities, such as swimming, cooking, and driving, can be dangerous. Several studies of motor vehicle crash data by age have shown that young people aged 16 to 29 years were most likely to be in crashes caused by the driver falling asleep. Falling asleep while driving could be fatal to the patient and others, and for this reason, it is imperative that a physician discuss driving privileges with any patient with narcolepsy. The AMA and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration recommend ceasing or denying driving privileges in those in whom narcolepsy is diagnosed. These privileges may be reinstated once the patient has undergone treatment and no longer has excessive daytime sleepiness or cataplexy.8 The Epworth Sleepiness Scale can be a useful tool in assessing levels of daytime drowsiness.9

OUTCOME OF THE CASE

On follow-up evaluation, narcolepsy and cataplexy were diagnosed. Oral modafinil (200 mg each morning) was prescribed. It is important to inform patients that modafinil is a stimulant. If taken late in the evening, it may cause insomnia. The patient has noticed gradual improvement in his symptoms of daytime wakefulness but continues to have intermittent sleep attacks, which we feel may be related to poor adherence to his medication regimen. To his dismay, we have not yet permitted him to obtain his driver's license.

References:

1.

Alexander ME, Berul CI. Ventricular arrhythmias: when to worry.

Pediatr Cardiol

. 2000;21:532-541.

2.

Pratt JL, Fleisher GR. Syncope in children and adolescents.

Pediatr Emerg Care

. 1989;5:80-82.

3.

Massin MM, Bourguignont A, Coremans C, et al. Syncope in pediatric patients presenting to an emergency department.

J Pediatr

. 2004;145:223-228.

4.

Strieper MJ. Distinguishing benign syncope from life-threatening cardiac causes of syncope.

Semin Pediatr Neurol.

2005;12:32-38.

5.

Kercher EE, Tobias JL. Anxiety disorders. In: Marx JA, Hockberger R, Walls R, eds.

Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice

. 6th ed. New York: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2005:chap 110.

6.

Ropper AH, Brown RH. Sleep and its abnormalities.

Adams and Victor's Principles of Neurology.

8th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2005:333-351.

7.

Kotagal S. A developmental perspective on narcolepsy. In: Loughlin GM, Carroll JL, Marcus CL, eds.

Sleep and Breathing in Children.

New York: Marcel Dekker; 2000:347-362.

8.

Wang CC, Kosinski CJ, Schwartzberg JG, Shanklin AV.

Physician's Guide to Assessing and Counseling Older Drivers

. Washington DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 2003:chap 9, sec 4. http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/olddrive/ OlderDriversBook. Accessed September 10, 2008.

9.

Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991; 14:540-545.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

10.

Horne JA, Reyner LA. Sleep related vehicle accidents. BMJ. 1995;310:565-567.

11.

Knipling RR, Wang JS. Crashes and Fatalities Related to Driver Drowsiness/Fatigue. NHTSA Research Notes. Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration; 1994.

12.

Maycock G. Sleepiness and driving: the experience of UK car drivers. J Sleep Res. 1996;5:229-237.

13.

Millman RP; Working Group on Sleepiness in Adolescents/Young Adults; AAP Committee on Adolescence. Excessive sleepiness in adolescents and young adults: causes, consequences, and treatment strategies. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1774-1786.

14.

Pack AI, Pack AM, Rodgman E, et al. Characteristics of crashes attributed to the driver having fallen asleep.

Accid Anal Prev.

1995;27:769-775.

15.

Thorpy MJ, ed.

Sleep MultiMedia

. Version 6.5 [DVD]. Scarsdale, NY: Sleep MultiMedia Inc; 2000.