Controlling Pediatric Migraine-Continued

I read with keen interest Dr Jack Gladstein's article, "Pediatric Migraine: Strategies for Maintaining Control," in the August issue of CONSULTANT FOR PEDIATRICIANS (page 316). It prompted several follow-up questions, which I hope the author can respond to.

I read with keen interest Dr Jack Gladstein's article, "Pediatric Migraine: Strategies for Maintaining Control," in the August issue of CONSULTANT FOR PEDIATRICIANS (page 316). It prompted several follow-up questions, which I hope the author can respond to.

First, Dr Gladstein notes that trials of triptans in children have shown good efficacy, but he says that no triptan has yet been FDA-approved for use in children. What was the nature of the trials that showed good efficacy-and why haven't pharmaceutical companies pursued pediatric indications for these agents?

Could the author describe his preferred approach for administering a triptan to a child who is having an acute migraine episode? Does he prefer any specific agent? To calculate the dosage, does he use a formula based on the child's weight and age?

Finally, could Dr Gladstein describe in more detail his approach to migraine prophylaxis in children? What is the role of β-blockers (eg, propranolol) in prophylaxis in children?

--Robert P. Blereau, MD

Morgan City, La

Many attempts at showing efficacy in triptan trials in children have been unsuccessful because of the very high rate of placebo response. There are many studies that demonstrate that triptans are safe and efficacious in children but few that show an advantage of triptans over placebo. Lewis and colleagues published a good review in Headache.1

Since this review was published, Evers and colleagues2 conducted a double- blind, placebo-controlled crossover study of oral zolmitriptan in children. They administered placebo, zolmitriptan, and ibuprofen to all participants for the treatment of 3 consecutive migraine attacks. Pain relief rates after 2 hours were 28% for placebo and 62% for zolmitriptan. The spread in efficacy between placebo and zolmitriptan approached statistical significance.

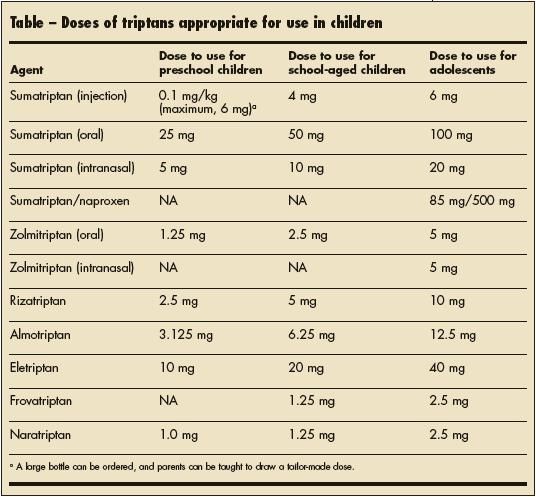

Almost all triptans come in doses small enough to permit safe treatment of school-aged children. See the Table for the appropriate doses of available agents in children of various ages.

Table

With regard to prophylaxis, no preventive medication has been shown to be any better than the others in children. Base the choice of a preventive agent on the presence or absence of other comorbid conditions. For example, propranolol cannot be used in a child who has asthma or who engages in vigorous exercise. Amitriptyline is recommended for migraine prophylaxis in children who have a sleep disturbance. Topiramate is great for patients with weight problems; conversely, valproate, amitriptyline, and cyproheptadine should be avoided in children who struggle with their weight, since these medications tend to result in some weight gain.

If a child has no comorbidities, the family can make the choice of a preventive agent based on adverse-effect profiles. For example, I might tell parents that we have the most experience with amitriptyline but that it may cause their child to have problems waking up in the morning or may make his or her mouth dry; that topiramate may not produce any early morning problems but would require monitoring for subtle cognitive changes; and that valproate will likely result in their child's gaining a few pounds. On the basis of this information, we would choose an agent.

Dose all prophylactic medications using the "start low, go slow" principle. Increase the dosage until the desired effect is achieved.

Erratum: The last name of the lead author of the Photoclinic item "Bilateral Tibial Hemimelia" (Consultant For Pediatricians, September 2008, page 397) was misspelled. The correct spelling of the author's name is Susan Enayat-Pour. We regret the error.

References:

1.

Lewis DW, Winner P, Wasiewski W. The placebo responder rate in children and adolescents. Headache. 2005;45:232-239.

2.

Evers S, Rahmann A, Kraemer C, et al. Treatment of childhood migraine attacks with oral zolmitriptan and Nibuprofen. Neurology. 2006;67:497-499.