Attachment is the key to parent-child relationships

One physician’s personal agenda is to help parents understand how their own history of dealing with stress affects how they bond with their child.

Joseph Grant Cramer, MD, FAAP

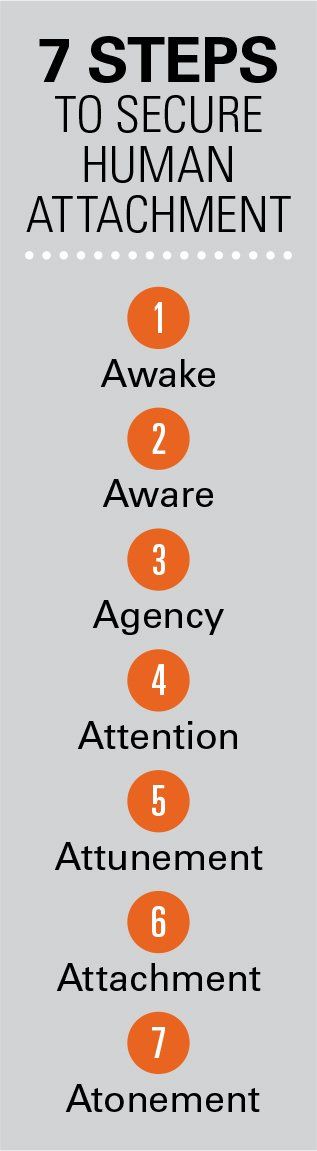

7 steps to secure human attachment

I don’t remember exactly my “Eureka” moment. For sure, it was not in a bathtub like Archimedes. My “a-ha” came more recently while dry behind the ears. At the time I was in a private practice doing what pediatricians do. The discovery was that most everything I was doing in my office was wrong. The problem was not treating asthma or rashes. It was how I executed the time-honored well-child care (WCC) visit.

In the fleeting moments between the exam and the shots, my conversation with the parents usually was filled with platitudes and medical jargon. Well visits were boring. The monologue was stale. I said nothing lasting.

Further, I knew zero about the mother, father, or family. I had no clue about the person in the exam room with me. What kind of parents were they? How did they handle a screaming kid? What made them tick? Did they know love? Personally, knowing anxiety and depression, I worried about the parents in my practice. Were they equally struggling with their moods? How did it affect their parenting? Because I knew what a pain in the butt these conditions were, I wanted to help anyone with the same challenges.

“When the student is ready, the teacher will appear.” Perhaps it was the glowing embers of burnout. Whatever the igniting spark, I was ready. The teacher who appeared was Dr. Richard Ferre.

Proponents of “attachment”

Richard C. Ferre, MD, is the former chairman of the Department of Child Psychiatry at the University of Utah School of Medicine and Primary Children’s Hospital in Salt Lake City. He opened my mind to real pediatrics. The converting scripture was Daniel J. Siegel’s The Developing Mind.

Siegel’s book, one of many he has authored, introduced me to a brand-new world. It was as if I had followed the White Rabbit down the hole falling into an amazing wonderland. From its pages, I met Dr. John M. Bowlby, the godfather of child attachment theory. His work began with the millions of orphaned and displaced children after World War II. He continued to formulate his thinking, borrowing the studies of children forced to be alone by the British “stiff upper lip” policy during prolonged stays in the hospital. Bowlby was familiar with Konrad Lorenz and his imprinted gaggle of goslings. He added to his theory the behavioristic research of Harry F. Harlow of young primates clinging to the terry cloth “mother.” From this emerged the articulation of a secure base. Mary Ainsworth, Mary Main, and a pantheon of other thinkers and doers of the child and parent relationship became my heroes.

Attachment is the keystone

Archimedes by water displacement figured out the king’s crown was not pure gold. I discovered the gold. It is human attachment. The parent bonds to the child. The child attaches to the mother/father. The word “security” jumped out from the pages blinding me. It clarifies everything. The lack of security explains my own state of mind. Security and insecurity describe human behavior. Attachment’s propagation through the generations is the essence of parenting. Its absence in the pediatric WCC-visit curriculum is the missing keystone for caring for children.

The message to every new parent is their power to influence their child’s brain development. Nurturing is essentially the positive repetitive task of managing energy-in the vernacular, stress. It follows that it is critical to uncover his or her child’s mental model to handle tension. One of Dr. Ferre’s pearls was, “The job of the brain is to process information and manage energy.”

Attachment is now my practice and personal mantra. Mindfulness follows. My WCC agenda is to help every parent understand his/her mental model to deal with stress; ie, the child. To understand the parents’ intuitive behavior, I ask them to share their most frightful memories of childhood. Their brains draw from their nonverbal hemisphere stories that reveal a hidden clue to their stress energy management. It is the internal blueprint they use to deal with their child. A non–story is a story of avoidance.

The one question “What is the scariest thing you remember in your childhood?” is the revelatory key to open the mind. Over the years it has revealed a treasure trove of tales. The most ordinary parent sometimes has the most extraordinary story. There are the recollections of nightmares soothed by the sleepy parent. Another shared narrative is being lost but when found, being soothed with hugs. Tragically, quite a few stories do not have a happy beginning to the nearly 9.5 million minutes from birth to age 18 years. Sadly, there are repeated descriptions of violence or abandonment. Memories of dads pointing guns have been shared more than once. One patient told how her father put a gun to her head when she was about 6 years old. Her mother voiced her own craziness: “Go ahead and shoot. When the police come, they will know what idiot did it.”

Another patient remembered the night the mother said she was leaving, never to return. Today I learned a mother’s terrifying story recalling how at the age of 3 years she phoned the police because her parents were so violent. Imagine being 3 years old needing to know how, then calling the cops. One mother telling her personal history for a brief second transformed into her own alcoholic parent with a louder deeper voice and mean face leaned threateningly toward me.

Knowing the story plus how a parent tells it gives a glimpse into what he or she does when the child comes for succor. The memory prompts rapid, nonspecific, nonspoken reaction. If the parent’s tale is without a secure person, his or her spontaneous action will be more dismissive. “You are fine” is the automatic response. Decreased empathy is the result. The child is on its own. This by itself is not bad. Talk to the self-starters. It is a problem when the emotional skills run out. Avoidance of relationships, loneliness, procrastination, freezing, and fleeing take over.

Measuring security

Mary Ainsworth’s contribution is the standard test to measure security. Her research has been duplicated thousands of times around the world. In this experiment, the child is stressed by the mother stepping away, leaving the toddler with a stranger. How the child and the mother react upon leaving and reuniting can reveal how the parent had or had not matched the child’s needs. Their actions often link back to the parent’s story.

In one scenario, the child cries with the mother, cries when she leaves, and cries when she returns. Obviously, the presence of the mother is not soothing. This is labeled insecure ambivalent. In another setting labeled avoidant insecure, the child shows no emotion either on separation or return. However, the hidden sympathetic tone is as high as with the child who cries continuously in the mother’s presence This is the child with whom the parents take pride in how well adjusted he/she is. Instead, it is the opposite. The presence of the mother does not calm the internal storm.

The secure child cries but quiets with the reappearance of the mother. With the child’s secure base again in the room, the child goes off to play. Secure parenting teaches that stress has limits in time and intensity. More importantly, the baby learns for a lifetime that he or she is not alone.

Steps to attachment

As doctors, our first task is to awake our parents to the grandeur of their role as creators. They move from making a baby to creating a child. We do that with our sincere efforts to arouse them to the unbelievable beauty of their baby. Gazing at a baby’s face is incentivized by the large eyes and rounded red face, and by the baby’s imitating expressions back to the parent. I want the mother to gaze upon her beautiful child. I want them to at least think “Wow, wow, wow” (the last mortal words of Steve Jobs). In the world of complexity to increase probability, nature has made a baby beautiful to promote our connection. Studies show children imitate almost out of the womb. Very early on a child can tell the difference between a sad, happy, and angry face. The mother transmits emotion information to the infant, downloading lifetime files of happiness, sadness, joy, and fears.

Next, the parent must be aware of his/her own mental model of energy regulation. Self-awareness is not a gift bestowed upon everyone. Alexithymia, the inability to read internal or external emotions, can inhibit this skill. In 1 study, the capacity to recognize emotional expressions was enhanced by the mere practice. In another, maternal iron depletion contributed to poor reading of emotional signals. Unfortunately, borderline personality disorder, a form of attachment disruption, is a barrier to this reading as well.

Third, agency in a complex system permits choices. In the chaos of humans and our relationships, we are agents. We do not follow linear Newtonian courses of launched rockets. Oftentimes, after sharing a truly horrific memory, the parent, commonly the dad, says he is going to be different. In the clinic yesterday, a father and mother expressed gratitude to their absent parents. Thanks to their parents’ neglect, they know what not to do.

Fourth, without attention it is impossible to watch, listen, learn, touch, read needs, and react accordingly. Attention is the blossom and the fruit of mindfulness. Paying attention means a parent actively eliminates distractions, unplugs the screens, skips the trivial. Concentration permits seeing the previously unseen. To that end, meditation is the brain homework to increase function of the prefrontal cortex (PFC). Engage the PFC; rev up the power to discover.

Fifth, attunement is the actual emotional connection of parent brain to child brain, DNA to DNA. Here is where the epigenetics of change takes place. Opening and closing zones of the transcription, altering the histones and microRNA, all play some potential role. Simple stroking can influence methylation.

Sixth, attachment is the culmination of all the previous steps. The parents are awake, aware of their style of interaction that matches the child’s needs. They choose to follow their positive model or elect to be different. They are attentive to the child’s needs. They react brain to brain. The bond is solid; the attachment is secure.

Lastly, atonement is a word more often heard in religious corridors than in the hallways of the House of Medicine. In that setting, it is a reconciliation of humankind with God. It is becoming one with the divine. “At-one-ment” is a unity, a symbiotic fusion. In the universe of child-rearing, it is the harmony between parent and child. There is a shaping of a child in the parent’s own image.

Final thoughts

There is an Adam and Eve in every parent. The connection is manifested in the influences parents make to their children’s DNA. It is the closeness sustained by rocking a child to sleep. It is the nearness when parents read to their babes or sing them lullabies. It is hugging them when they crash or kissing their ouchie. Atonement, or this spiritual symbiosis, comes from lying on their bed to hear the details of the day or the tragedies of a teenager. It is a oneness built of sharing stories of life. It means there is more to parenting than the mechanics. There is an additional dimension that we should not ignore or pretend that it does not exist.

This is real pediatrics. It is the creation of a healthy, happy, loving, secure child.

Maybe that is what Archimedes meant when he ran naked down the street shouting “Eureka!”