Hugging is healing for NICU babies

Trained volunteer cuddlers provide the magic of human touch to help preemies and convalescing newborns thrive.

Edmund F La Gamma, MD

Figure

Aric Melzl

A diaper for the smallest, most delicate babies

For more information

Today’s high-tech neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) buzz with staff doing what they can to ensure the smallest and sickest of newborns survive. Yet amid the machines, equipment, and attentive nurses and doctors, there might be ordinary people, called cuddlers, softly singing to, talking to, cuddling, and gently rocking the preemies and convalescing newborns with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), known as opioid withdrawal.

As it turns out, low-tech cuddling, or hugging, also plays a role in helping these babies to survive and, even, thrive, according to Edmund F. La Gamma, MD, chief of Newborn Medicine and professor of Pediatrics, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Maria Fareri Children's Hospital, New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York.

“This whole concept of human contact is something that we often don’t pay attention to in the environment of a hospital and intensive care unit. Often, we become focused on lab values and blood gases because that’s keeping patients alive,” La Gamma says. “Sometimes, the aspect of humanness . . . is lost in the shuffle of intensive care.”

The need for touch is especially important for babies born prematurely or addicted to drugs like opioids. Take the babies who are born at weights below 1000 grams and earlier than 28 weeks’ gestation, for example. In the best case scenarios, those babies will be hospitalized for 2 to 3 months in order to grow from their extremely small size, La Gamma says.

These babies are exposed to many sounds, lights, and external stimuli not normally experienced in utero during normal brain development and often have problems with organization of motor function, La Gamma says.

“Normally, they would be in the uterus, rolled up like a ball, nice and quiet and in the dark,” he says. “But no matter how you provide services in intensive care, there is going to be light and much more disruption. The hugging is calming and tends to focus their attention, decrease motor activity, and embrace the sound to a human voice.”1,2

Nurses on these units are often busy with lifesaving measures and care, and parents can’t always be there to provide that nurturing touch. So, to address the softer side of care for patients in NICUs, pediatric inpatient units and sometimes birthing pavilions and hospitals nationwide are offering cuddling programs, in which volunteer trained cuddlers maintain cuddling when parents and staff can’t.

“Volunteer cuddler programs have the potential to enhance the human caring aspects of complex technological nursing care provided premature infants,” according to a paper published in 1990.3

“Although the fragile premature infant may not always appear to respond overtly, the weight gain, and social and mental development of the cuddled babies give testimony to the effectiveness of human attention. The infants' improved well-being and subsequent earlier hospital discharge as a result of cuddling are convincing rationale to implement a cuddler program,” the study authors write.

Addressing the need

In 2015, Kimberly-Clark Corporation (Dallas, Texas), manufacturer of the Huggies diaper brand, worked with the Canadian Association of Pediatric Health Centers to summarize the evidence of the powerful and positive impact a caregiver’s touch can have on babies’ comfort and development of brains and bodies, according to Aric Melzl, Baby and Child Healthcare general manager in North America. The resulting Huggies-funded white paper “The Power of Human Touch for Babies” cites research suggesting human touch offers many benefits for babies-from improved physiologic stability and regulation to enhanced immune system development and improved parent-baby bonding.4

“[I]t became clear that too few babies, especially those in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), receive the optimal amount of beneficial touch from parents or caregivers. Volunteer hugger programs can help fill this important need. And so, the No Baby Unhugged grant program launched in Canada in 2015 and was brought to the United States in 2016,” Melzl says.

No Baby Unhugged provides $10,000 grants to US hospital NICUs for hugging, or cuddling, programs. So far, 19 hospitals (15 in the United States and 4 in Canada) have received the money to launch new volunteer hugging programs or enhancing those they have.

“Huggies will continue to award grants in 2018, and hospitals interested in applying can visit HuggiesHealthcare.com to complete an application,” Melzl says.

The need for hugging programs could be on the rise, as the number of US babies who could benefit from such programs grows. During the past 25 years, preterm births in the United States have increased more than 35%, according to a study published in 2010.5

Thanks to advances in care, infants can survive at 22 weeks’ gestation, but the result is spiraling healthcare costs. This makes it imperative, the same authors suggest, for hospitals to focus on making clinical improvements that not only result in healthier babies but also help to manage costs.5

“Volunteer hugger programs can facilitate improved overall development of baby, improved parent-baby connection, and shorter stays in the NICU-in addition to freeing up time for nurses to continue their vital duties,” according to Melzl.

Grant recipients share stories

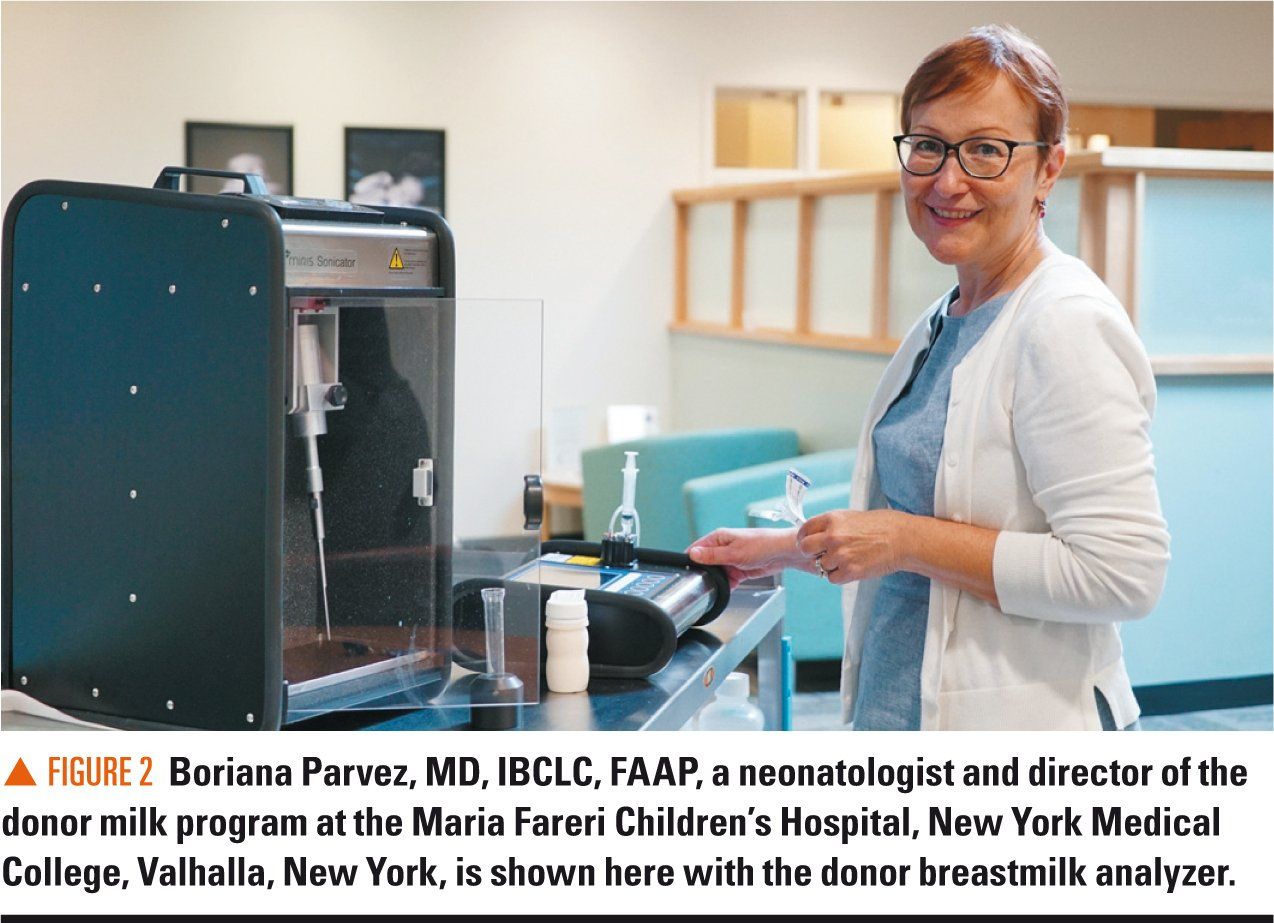

No Baby Unhugged grant recipient Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital used the $10,000 to enhance its existing cuddler program, according to Boriana Parvez, MD, IBCLC, FAAP, a neonatologist and director of the hospital’s donor milk program.

“We used [the grant] to develop a detailed education program, dedicated to the cuddlers. It’s specifically to educate them about the needs of these patients--how to pick up when the patient is becoming unstable, so they’re obviously no longer suitable to be held; how to respond to the baby’s general cues,” Parvez says. “We also used the funds to purchase new reclining chairs. Obviously, these chairs are used by the cuddlers during the day, but they’re also utilized by the parents when they come to visit their babies. We also find that these chairs are comfortable for promotion of breastfeeding.”

Although Maria Fareri Children’s Hospital, which received the Huggies’ grant in August 2017, hasn’t conducted studies looking at program outcomes, Parvez says that, anecdotally, nurses have told her they can better concentrate on the medical needs of the patients when huggers are there.

“At the same time, they feel the other needs of the babies are met. The babies are receiving the warmth and human touch that they need while their parents are not at the bedside,” Parvez says.

Parvez says the need for cuddlers is heightened for what she says are growing numbers of babies born to opioid-using mothers. In many cases, these mothers are incarcerated or they might live too far away to visit daily. Sometimes, families have to go back to work and can’t be at the bedside day and night. In other cases, family members simply need a break to take a nap or to go home, and cuddlers can relieve them.

Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, Lebanon, New Hampshire, also received the Huggies’ grant in August 2017 and used the grant to expand an existing cuddler program, according to Deirdre Sheets, RN-C, MSN, quality practice patient safety nursing specialist and cuddler program coordinator at Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock.

“Our infant cuddler program had initially begun in the summer of 2013 on the inpatient pediatric unit to help support our moms and babies who were going through withdrawal. About 9 months after we started there, the intensive care nursery approached me about expanding the cuddler program, with a particular focus on the babies who were going to be there for a longer-term hospitalization, which could be anywhere from a few weeks to a few months,” Sheets says.

The grant money helped the hospital to buy special chairs, which are comfortable, and rock, recline, and slide, for the intensive care nursery. Having the right chair is important, Sheets says. Cuddlers are encouraged to read and sing to the babies, while rocking or gently moving in the chair. The soothing motion, she says, helps to calm the babies.

The grant to Children’s Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock was also used to buy compact disc players and soothing music, including lullabies and soft piano, as well as snuggle wraps, which are fairly tight wraps that help to soothe babies who are going through withdrawal, according to Sheets.

“Music has also been demonstrated to help lower respiratory rates and pulses when a baby is upset,” Sheets says.

A recent study found that premature infants in a NICU who were exposed to music had lower respiratory rates, while heart rates increased in the no-music control group.6

Sheets says that although the hospital has not conducted studies on whether the program helps, the fact that staff and families are requesting additional cuddlers on weekends and evenings suggests the program is a win for clinicians and patients’ families.

Words of wisdom for a good cuddler program

Training, beyond regular volunteer training at a hospital, is important for cuddlers, according to Sheets. “Our cuddlers go through regular volunteer training, but then they spend between 6 to 8 additional hours training specifically to be able to cuddle the babies,” she says.

It’s also important to have buy-in from the hospital’s volunteer services department on the cuddler program, according to Sheets.

“Volunteer services definitely has a part to play in this and does a lot of the background checks. They do the initial orientation piece, as far as patient confidentiality, hand hygiene--some of those hospital-wide things that volunteers need to know,” Sheets says.

Nurses at the Children’s Hospital then teach volunteers about what they’ll need to do on the unit with the tiny babies. Volunteers learn how to change diapers, do appropriate bottle feedings, and more.

Finally, not every well-meaning person is cut out to be a cuddler, according to Sheets. “These are very special babies. They have a lot of needs. The cuddlers are not going to be holding a baby that’s going to sleep the whole time. That’s an important piece for people out in the community to understand,” she says. “So, the screening of the cuddlers, here, is initially done by volunteer services, but all cuddlers have to interview with somebody from one of the nursing units that’s involved. Then, we can really help them to understand what it is that they’re going to be doing when they’re here.”

Note to pediatricians

The importance of human touch isn’t a new concept to physicians, according to La Gamma. “The hand on the shoulder-it’s taught in medical schools,” he says. “But if we think about it, we can all relate to those feelings of personal touch--the hug you get from a loved one. There’s something about that human contact that is very necessary to anchor us in our humanity.”

References:

1. Loewy J, Stewart K, Dassler AM, Telsey A, Homel P. The effects of music therapy on vital signs, feeding, and sleep in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2013;131(5):902-918.

2. Zentner M, Eerola T. Rhythmic engagement with music in infancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(13):5768-5773.

3. Fritsch-deBruyn R, Capalbo M, Rea A, Siano B. Cuddler Program provides soothing answers. Neonatal Netw. 1990;8(6):45-49.

4. Benoit B, Boerner K, Campbell-Yeo M, Chambers C. The power of human touch for babies. Canadian Association of Paediatric Health Centres. Available at: https://www.huggieshealthcare.com/en-us/power-of-hugs/human-touch-for-babies. Accessed April 5, 2018.

5. Kornhauser M, Schneiderman R. How plans can improve outcomes and cut costs for preterm infant care. Manag Care. 2010;19(1):28-30.

6. Caparros-Gonzalez RA, de la Torre-Luque A, Diaz-Piedra C, Vico FJ, Buela-Casal G. Listening to relaxing music improves physiological responses in premature infants: a randomized controlled trial. Adv Neonatal Care. 2018;18(1):58-69.

7. Dore S, Esser, M, Fitzgerald F, et al; Huggies Nursing Advisory Council. Every change matters: a guide to developmental diapering care. Available at: https://www.huggieshealthcare.com/en-us/clinical-resources/every-change-matters/quick-guide-to-developmental-diapering-care. Published October 6, 2016. Accessed April 5, 2018.

8. Esser M. Diaper dermatitis: What do we do next? Adv Neonatal Care. 2016;16(suppl 5S):S21-S25.

Artificial intelligence improves congenital heart defect detection on prenatal ultrasounds

January 31st 2025AI-assisted software improves clinicians' detection of congenital heart defects in prenatal ultrasounds, enhancing accuracy, confidence, and speed, according to a study presented at SMFM's Annual Pregnancy Meeting.