Nasal Congestion and Intermittent Fever in Girl With Transient Hypogammaglobulinemia of Infancy

A 51⁄2 -year-old girl was brought to her pediatrician’s office by her mother, who reported that her daughter had a 1-week history of nasal congestion, intermittent fever, and cough that was worse in the morning and at night. The child was alert and smiling and appeared to be in no apparent distress.

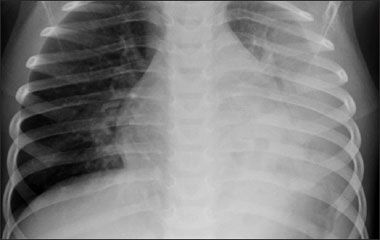

Figure 1 – In this radiograph, obtained during the patient's first episode of pneumonia, cystic lucencies visualized within the left lower lobe are representative of a necrotizing presentation.

A 5½-year-old girl was brought to her pediatrician's office by her mother, who reported that her daughter had a 1-week history of nasal congestion, intermittent fever, and cough that was worse in the morning and at night. The child was alert and smiling and appeared to be in no apparent distress.

Physical examination. The patient's oral temperature was 36.6°C (97.9°F). Tympanic membranes were dull, nares were crusty, and palpation revealed tenderness over the maxillary sinuses. No lymph nodes were palpable. Lungs were clear to auscultation bilaterally and in all lobes.

History. The patient was born to a gravida 1 para 1 mother via normal vaginal delivery after an uncomplicated pregnancy. She was first seen by her current pediatrician for a well-child visit at age 15 months. At that time, the mother noted that her daughter had had 4 episodes of otitis media in the preceding 3 months. When she was 18 months old, a necrotizing pneumococcal pneumonia developed (Figure 1), for which she was hospitalized. Although the culprit organism was not resistant, the child's condition did not respond to initial antibiotic therapy. During the 10-day hospitalization, she required intravenous antibiotics and a pleural chest tube. Following hospital discharge, she received therapy with oral amoxicillin for 4 weeks. The month following discontinuation of the amoxicillin-while she was still healthy-the patient received the pneumococcal vaccine. Nine months later, pneumonia was diagnosed again; this time, treatment with intramuscular ceftriaxone was successful.

This second pneumonia and a thorough review of the patient's medical history prompted concern for possible immunodeficiency. Serum immunoglobulin levels were obtained. Laboratory tests revealed a slightly decreased total IgG level of 518 mg/dL (normal range, 546 to 1533 mg/dL) and a decreased IgG1 subtype level of 268 mg/dL (normal range, 381 to 884 mg/dL). Although she had received both the pneumococcal and Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) vaccines, studies demonstrated no evidence of seroconversion to either organism (although tetanus antibodies had developed following vaccine administration). On the basis of the medical history and laboratory results, transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy (THI) was diagnosed.

Since receiving the THI diagnosis, the child has had a history of chronic sinusitis. At this visit, sinusitis and impetigo of the nares were diagnosed.

THI: AN OVERVIEW

THI is a self-limited, primary immunodeficiency caused by an abnormal delay in the establishment of immunoglobulin synthesis during infancy. The disorder results in recurrent infections until the condition resolves-usually by age 4 years.1,2 THI is estimated to occur in 1 in 10,000 children, affects males and females equally, and has no ethnic predilection.1 Children between the ages of 2 and 48 months are those most often affected.1

Pathophysiology. Normally, by birth an infant has obtained a full complement of IgG from the mother. Infants typically begin synthesizing their own IgG around the beginning of the second month of life.3 However, as acquired IgG levels begin to decrease, levels of actively produced IgG are still low. Thus, a normal physiologic nadir in IgG levels ensues between ages 3 and 6 months.1

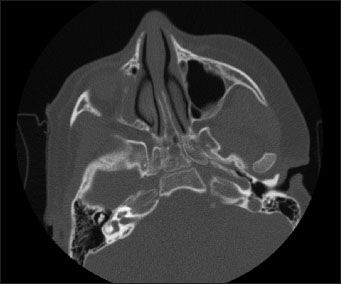

Figure 2 – A head CT scan revealed complete opacification of the right maxillary sinus, indicative of sinusitis. The left maxillary and sphenoidal sinuses appeared normal. The frontal sinus is typically not well developed in this age-group.

In a child with THI, the initiation of physiologic IgG production is delayed. The precise cause of the delay is not known.1 However, it is theorized that a defect in the number and function of T helper cells may hinder the differentiation of B cells into antibody producers (although there is no intrinsic defect in the B cells themselves).1,4 As acquired IgG is metabolized, IgG levels do not recover at a normal rate. A prolonged immunodeficiency results. The deficiency is manifested in recurrent infection-most commonly otitis media, chronic cough, and bronchitis.1 Shapiro and colleagues5 have also correlated IgG deficiency with chronic sinusitis. In this patient, THI has manifested most frequently as sinusitis over the past 3 years (Figure 2).

Management. THI is a self-limited disorder, with most patients recovering between the ages of 18 and 48 months. Management is primarily supportive. Immunoglobulin levels should be periodically monitored. In patients with severe recurrent infections, intravenous IgG is indicated for 12 to 36 months.1 In one study, disease progression and recovery were observed in 40 patients with THI.6 Only 2 of these patients received immunoglobulin replacement therapy. In 33 of the children in the study, immunoglobulin levels were up to par by age 36 months. However, 7 patients had persistently low levels at ages ranging from 40 to 57 months.

In this patient, immunoglobulin levels have been monitored every 2 to 6 months, with progressive increases noted in IgG and IgG1 levels over time. When last checked, her subtype level was only slightly low. However, she has continued to have intermittent sinus infections. Her primary care pediatrician has been following her closely, in conjunction with an otolaryngologist. After 2 additional pneumococcal vaccinations and 1 additional Hib vaccination, the patient has shown adequate production of antibodies to both organisms.

The patient's parents have regarded her health as their utmost priority. They have diligently monitored her condition and have made every effort to promote her health. Both mother and father worked to restructure their work and family life to avoid placing their daughter in a group day-care setting. By achieving this goal, they were able to eliminate a major risk factor for pediatric infection.7,8

CONSIDERATIONS WHEN MANAGING CHRONIC ILLNESS IN CHILDREN

The same efforts that have helped optimize this child's health may also have had adverse effects. The care of a child with any chronic illness often causes stress and anxiety among parents. Review of telephone triage and appointment notes in this patient's chart revealed numerous and regular parental calls to the office triage nurse and frequent ill-child visits. A relatively large percentage of these calls and visits appear to have been prompted by rather minor and very early-stage symptoms, often unaccompanied by fever.

Chronically ill children often experience psychosocial effects from efforts to care for them. In their attempts to protect their daughter, this girl's parents significantly limited her interactions with other children. However, peer interaction is an essential aspect of development at all stages of childhood.9 A study by Erwin and Letchford10 found that the minimal peer contact of children kept at home during their preschool years correlated with decreased social development, compared with children enrolled in preschool programs.

KEY POINTS FOR YOUR PRACTICE

A delicate balance must be struck between the goal of safeguarding the health of a chronically ill child and that of promoting the psychosocial health of both child and family. Anticipatory guidance and support on the part of the pediatrician are essential to achieving this balance.

OUTCOME OF THIS CASE

At the current visit, the patient's pediatrician prescribed oral augmentin, 900 mg bid, for her sinusitis and impetigo of the nares. The child's mother was instructed to return for a follow-up visit, if needed; at the same time, the physician reminded the mother of her daughter's progressively recovering immunoglobulin levels and reassured her regarding the steady diminishment of the child's THI. (Her test results demonstrate nearly recovered IgG levels.)

Although her parents were hesitant, the patient did attend kindergarten last year and is currently preparing to enter the first grade. Her parents reported that she acclimated well to the school environment and made friends with several children in her class.

An ongoing goal for this patient is continuing development of social competence. As recommended by the current Bright Futures guidelines, 9 her parents will be encouraged to promote this development by arranging for opportunities for social interactions, such as participation in team sports or group activities. Efforts to promote parental and family mental health will also be an ongoing part of her care. Her pediatrician will continue to reassure her parents about the self-limited nature of THI and the evident improvement in their daughter's status. In addition, monitoring of patient and parental psychosocial states will continue, with timely mental health care referral, if the need arises.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Gandy AC. Pediatric Database [computer software]. Version 1.5s. 1998.

2.

McCance KL. Structure and function of the hematologic system. In: McCance KL, Huether SE, eds.

Pathophysiology: The Biologic Basis for Disease in Adults & Children.

4th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 2002:811-842.

3.

Wong DL.

Whaley & Wong's Essentials of Pediatric Nursing.

5th ed. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1997.

4.

Siegel RL, Issekutz T, Schwaber J, et al. Deficiency of T helper cells in transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy.

N Engl J Med.

1981;305:1307-1313.

5.

Shapiro GG, Virant FS, Furukawa CT, et al. Immunologic defects in patients with refractory sinusitis.

Pediatrics.

1991;87:311-316.

6.

Kiliç SS, Tezcan I, Sanal O, et al. Transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy: clinical and immunologic features of 40 new cases.

Pediatr Int.

2000;42:647-650.

7.

Lu N, Samuels ME, Shi L, et al. Child day care risks of common infectious diseases revisited.

Child Care Health Dev.

2004;30:361-368.

8.

Churchill RB, Pickering LK. Infection control challenges in child-care centers.

Infect Dis Clin North Am.

1997;11:347-365.

9.

Green M, Palfrey JS, eds.

Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents.

2nd rev ed. Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health; 2002.

10.

Erwin PG, Letchford J. Types of preschool experience and sociometric status in the primary school.

Soc Behav Pers.

2003;31:129-132.