Sialoadenitis in a Teenager

Fifteen-year-old girl with several- day history of worsening right-sided facial pain and swelling. Pain severity 10 on a scale of 1 to 10. Limited oral intake.

HISTORY

Fifteen-year-old girl with several- day history of worsening right-sided facial pain and swelling. Pain severity 10 on a scale of 1 to 10. Limited oral intake.

No other symptoms. Patient denies fever, cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, recent illness, and any other previous similar episodes. No ill contacts. Immunizations up-to-date. Not taking any medications; no known drug allergies.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Mild tachycardia (109 beats per minute); other vital signs normal.

Patient alert, uncomfortable, but nontoxic-appearing. Right facial swelling anterior to the right ear extends to the jaw. Palpation of the right parotid gland produces tenderness: area firm, without overlying edema. Stensen duct erythematous, without discharge. Cranial nerve V and VII function intact.

IMAGING STUDIES

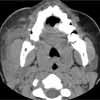

Facial CT scan as shown.

WHATS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

Facial CT revealed a 3-mm calcification in the distal portion of the parotid duct, diffuse enlargement of the parotid gland, and regional lymph node enlargement. After a dose of ampicillin/sulbactam, the patient was discharged with pain medication and a prescription for oral antibiotics. She was advised to apply warm compresses and to suck on sialogogues (sour candy). Follow-up with an otolaryngologist in 7 days was also recommended.

A day after her ED visit, the patient returned, complaining of worsening swelling and inability to swallow. She was hospitalized and given intravenous fluids and antibiotics, warm compresses, and parotid massage. These conservative measures were not effective and, on hospital day 4, the stone was removed in an open surgical procedure. The patient did well; she was given clindamycin and discharged the following day. Culture of the stone showed polymicrobial growth.

Etiology and Prevalence

Salivary stones--sialoliths--can arise in any of the salivary glands or their associated ducts. These stones or calculi are thought to form in the calcium-rich saliva under the conditions of stagnation created by the partial duct obstruction.1 They are composed of both organic and inorganic substances. The inorganic substance is composed primarily of calcium phosphate, with some magnesium, ammonium, and carbonate.2

Although autopsy reports have found salivary calculi in approximately 1% of the population,3 the majority do not cause symptoms. Symptomatic sialolithiasis may result in sialoadenitis--salivary gland inflammation and infection, as in this case. Sialoadenitis is uncommon in children.1

Diagnosis and Treatment

Sialolithiasis with sialoadenitis presents most commonly with pain and swelling in the area of the affected salivary gland. Either symptom may be present alone.1 The submandibular gland is most commonly affected, followed by the parotid glands. The sublingual glands are involved in only a small percentage of cases.1 Discomfort is often aggravated by eating.1

Physical examination is useful in the diagnosis. Stones may be palpable in the floor of the mouth in the case of the submandibular gland, and of the area around Stensen duct in the case of the parotid gland.1 Various imaging modalities may also be employed. Many stones are visible on plain films, but CT scans, ultrasonograms, and contrast sialograms may be necessary.1

This entity must be distinguished from other important causes of rapid facial swelling. These include Burkitt lymphoma, buccal cellulitis, hereditary angio-neurotic edema, cervical adenitis, and viral parotitis.

Some cases will resolve with conservative mea-sures--such as warm compresses, massage, and sialogogues. Pain medication and anti-staphylococcal antibiotics (when sialoadenitis is present) are generally part of the treatment plan as well.1 If these measures are inadequate, otolaryngology consultation for possible surgical intervention is necessary. Besides transoral sialolithotomy and occasional external sialoadenectomy, other options are available. These include sialoendoscopic retrieval, removal with fluoroscopy-guided wires, or even lithotripsy.1,4-7

Long-term obstruction by a stone can lead to atrophy, fibrosis, stricture, and even loss of gland function. Complications of management are local pain and inflammation, as well as recurrence. Xerostomia may follow sialoadenectomy of the submandibular gland.1

A Lesson for the Clinician

Acute facial swelling in a child may result from a variety of causes. Some of these may be serious. Burkitt lymphoma commonly involves the jaw.8,9 Buccal cellulitis--which is uncommon in patients who have been vaccinated against Haemophilus influenzae10--has a high association with bacteremia and meningitis.11,12 Hereditary angioneurotic edema can result in fatal laryngoedema.13,14 Other causes, such as cervical and facial adeni-tis and viral parotitis, are more common and carry a better prognosis.

Sialolithiasis with sialoadenitis is an uncommon cause of acute facial swelling. The clinician must distinguish accurately between this and other common and uncommon entities to provide appropriate care for children with acute facial swelling.

References:

REFERENCES:

1.

Williams MF. Sialolithiasis.

Otolaryngol Clin North Am.

1999;32:819-834.

2.

Hiraide F, Nomura Y. The fine surface structure and composition of salivary calculi.

Laryngoscope.

1980;90:152-158.

3.

Rauch S, Gorlin RJ. Diseases of the salivary glands. In: Gorlin RJ, Goldman HM, eds.

Thomas' Oral Pathology.

6th ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1970:997-1003.

4.

Marchal F, Dulguerov P. Sialolithiasis management: the state of the art.

Arch Otolaryn Head Neck Surg.

2003;129:951-956.

5.

McGurk M, Escudier MP, Brown JE. Modern management of salivary calculi.

Br J Surg.

2005;92:107-112.

6.

Capaccio P, Ottaviani F, Manzo R, et al. Extracorporeal lithotripsy for salivary calculi: a long-term clinical experience.

Laryngoscope.

2004;114:1069-1073.

7.

Drage NA, Brown JE, Escudier MP, McGurk M. Interventional radiology in the removal of salivary calculi.

Radiology.

2000;214:139-142.

8.

Amusa YB, Adedrian IA, Akinpelu VO, et al. Burkitt's lymphoma of the head and neck region in a Nigerian tertiary hospital.

West Afr J Med.

2005;24:139-142.

9.

Hupp JR, Collins FJ, Ross A, Myall RW. A review of Burkitt's lymphoma. Importance of radiographic diagnosis.

J Maxillofac Surg.

1982;10:240-245.

10.

Fisher RG, Benjamin DK Jr. Facial cellulitis in childhood: a changing spectrum.

South Med J.

2002;95:672-674.

11.

Walker JS, Corcoran KJ. Buccal cellulitis.

Am J Emerg Med.

1990;8:542-545.

12.

Lin WJ, Lai YS, Lo WT, et al. Cellulitis resulting from infection by

Hae- mophilus influenzae

type b: report of two cases.

Acta Paediatr Taiwan.

2004;45: 100-103.

13.

Boyle RJ, Nikpour M, Tang ML. Hereditary angio-oedema in children: a management guideline.

Pediatr Allergy Immunol.

2005;16:288-294.

14.

BorkK, Barnstedt SE.Laryngeal edema and death from asphyxiation after tooth extraction in four patients with hereditary angioedema.

J Am Dent Assoc.

2003;134:1088-1094.