A new diagnostic paradigm for celiac disease

Since the middle of the 20th century and into the 21st century, the incidence of celiac disease has been rising significantly throughout the Western world. Here is what you need to know about this autoimmune condition.

Celiac disease (CD) is an autoimmune disease in which a reaction to gluten consumption damages the small intestine. With a steadily increasing global prevalence of close to 1%1, public awareness of CD and gluten-related disorders has grown considerably over the last few decades.

Celiac disease is more common in children with the following risk factors:2

- A family member with CD or dermatitis herpetiformis

- Type 1 diabetes

- Down syndrome or Turner syndrome

- Autoimmune thyroid disease

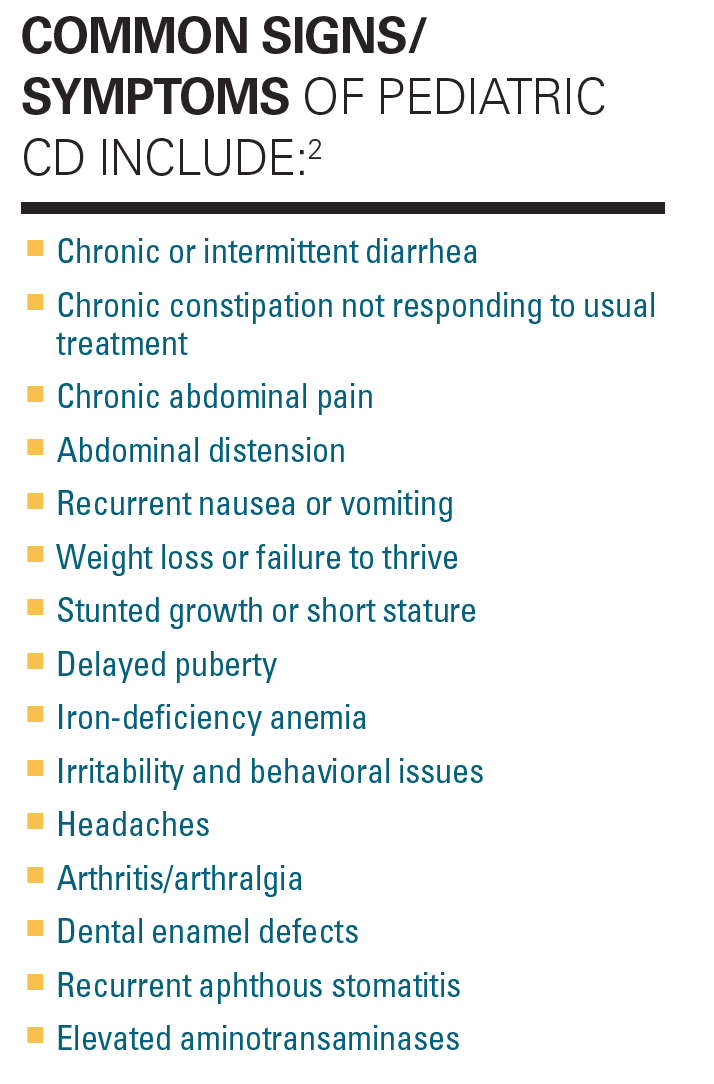

Celiac disease can be challenging to diagnose as patients may present with gastrointestinal and/or extraintestinal symptoms, and many are apparently asymptomatic.3 Furthermore, there is a poor correlation between gastrointestinal damage and symptoms.

Timely diagnosis of CD and optimization of nutrition is particularly important in childhood to prevent irreversible complications such as short stature and osteoporosis. All individuals with untreated CD are at risk for long-term complications, whether or not they present with symptoms.

Common signs/symptoms of pediatric celiac disease

With the growing prevalence of CD and the heterogenous, often non-specific nature of symptoms, many patients remain untested and diagnosis may be delayed by several years. Currently, it is estimated that 43% of the CD population remains undiagnosed.4

Like many autoimmune diseases, the exact trigger of CD is unknown; however, the genetic risk factors (HLA-DQ2/DQ8) are well defined.1,2 Additional environmental factors including infant-feeding practices, gastrointestinal infections, and the intestinal microbiome may all play a role.

Figure

Whatever the cause, when the body’s immune system mounts an attack against the “invasion” of gluten, the reaction damages the villi: slight hair-like projections that line the small intestine. This damage prevents the villi from performing the function of absorbing vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients, which means the celiac patient cannot get enough nutritional value from the food they’re eating.5 This can be especially disruptive to normal growth and development in children.

Left unchecked, chronic intestinal inflammation and malabsorption from CD can cause a host of complications, including:6

- Malnutrition

- Bone fractures

- Infertility and miscarriage (in adults)

- Lactose intolerance7

- Cancer, especially intestinal lymphoma and small bowel cancers

- Cardiac disease (myocarditis, cardiomyopathy)

- Neuropsychiatric disease

All of these comorbidities represent an enormous human toll, as well as an expensive strain on the health care system.

Updated testing recommendations

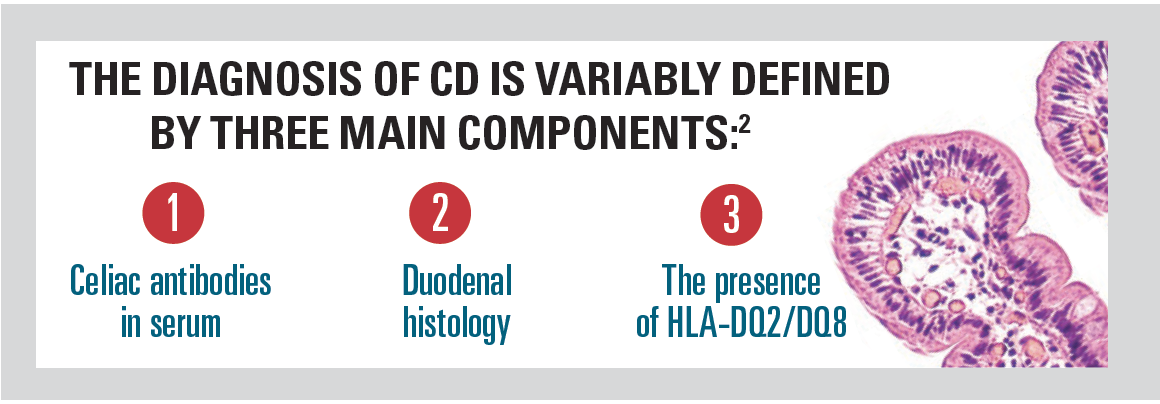

Historically, the cornerstone of CD diagnosis has been a duodenal biopsy with histological analysis.1 Now serological tests are available, each with a role to play: tissue transglutaminase-IgA (tTG IgA), total IgA, endomysial IgA (anti-EMA), and IgG-based tests.1

Given the time-consuming, expensive, and invasive nature of duodenal histology, there has been increased focus on finding the most efficient algorithm and omitting duodenal histology in patients who fulfill other CD diagnostic criteria.1

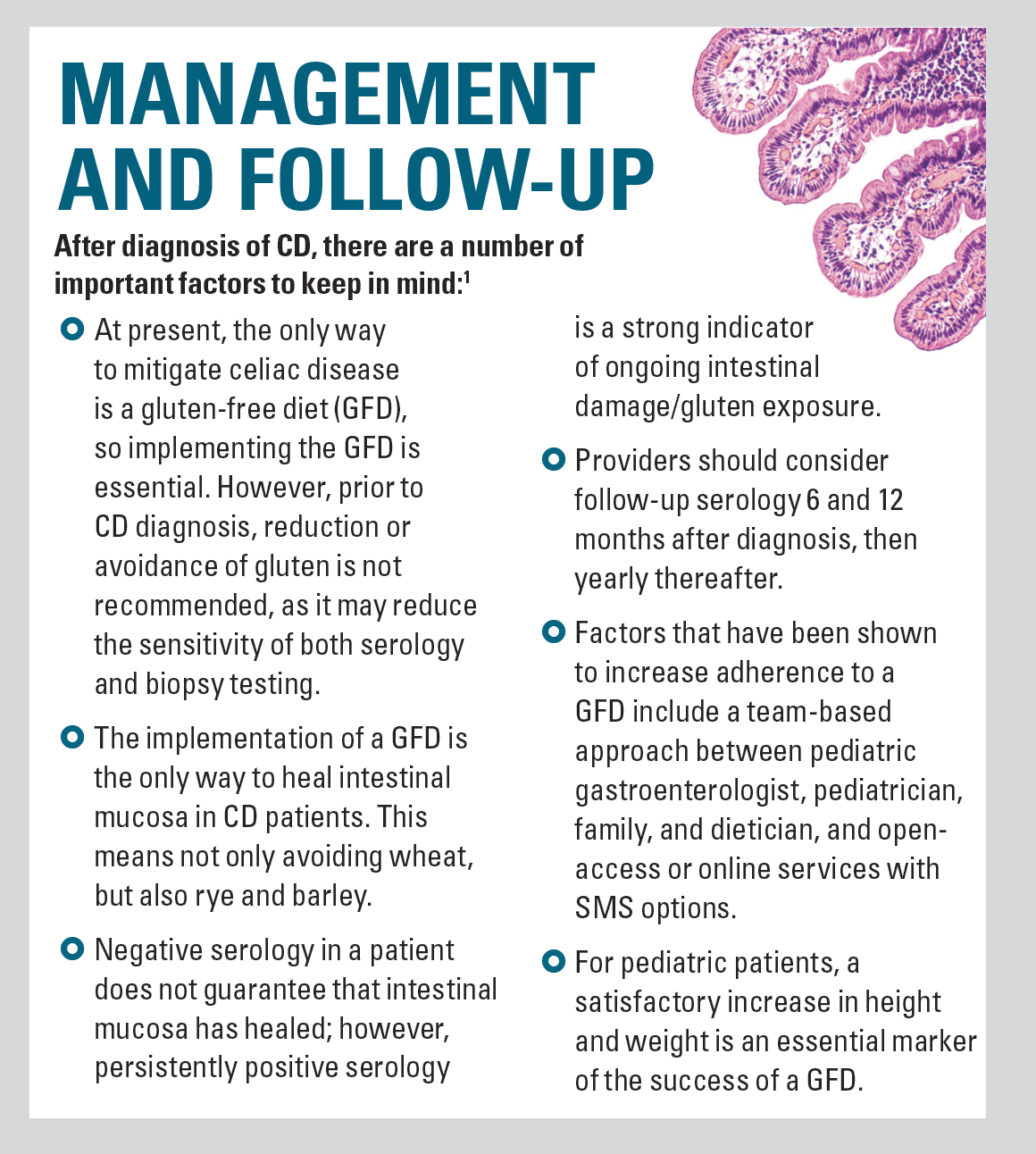

Management and follow-up

Recently, both the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) released updated guidelines for diagnosing CD.1,2 Both reports were based on available published evidence and emphasize that the diagnosis should be made by a specialist (eg, gastroenterologist).

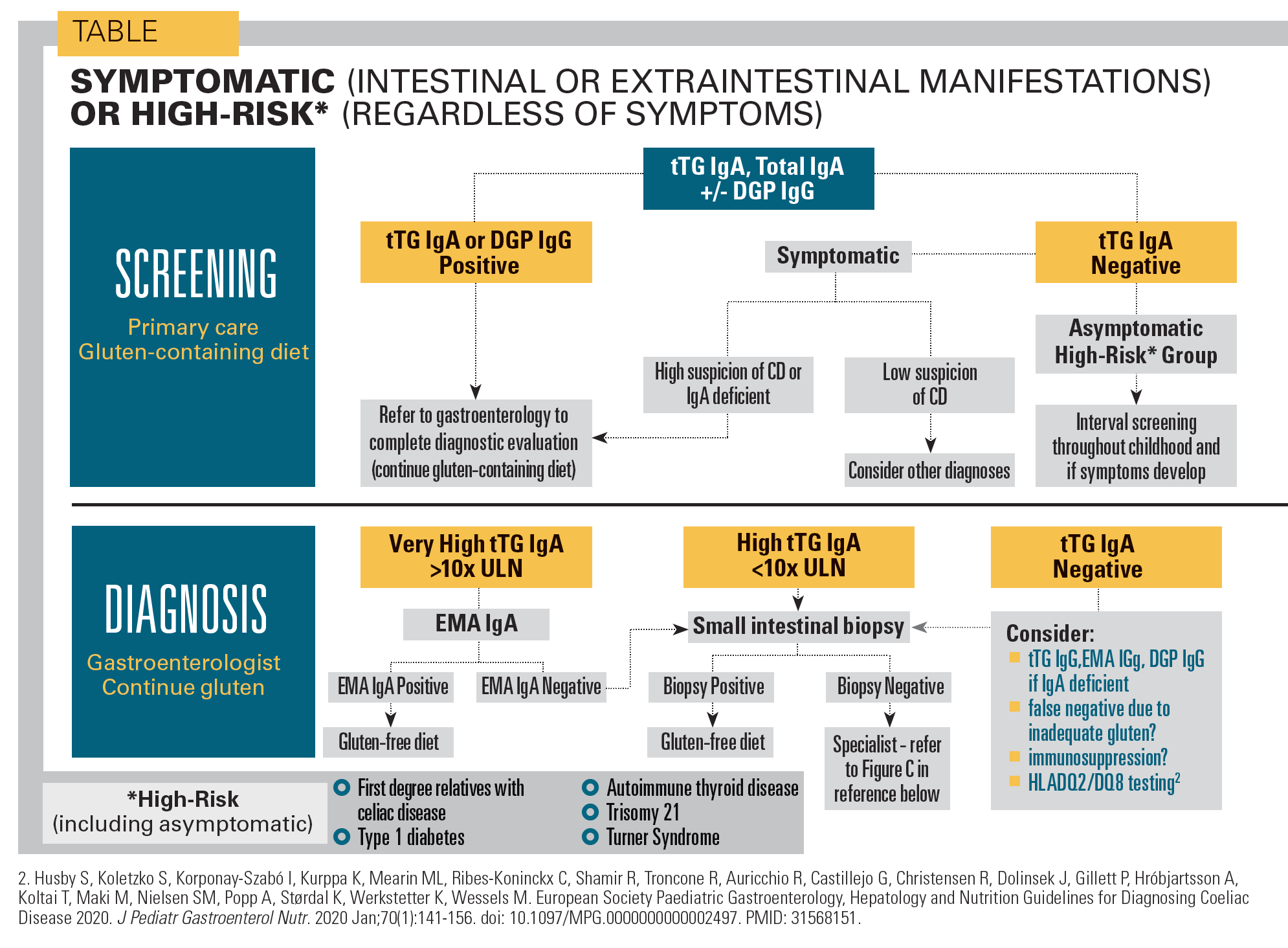

The pediatric testing algorithm

For pediatricians managing patients with symptoms of CD or an affected first degree relative, the recommended diagnostic approach is to begin with an initial test for total serum IgA in addition to a test for serum antitissue transglutaminase IgA antibodies (tTG IgA) as the child continues to consume a gluten-containing diet.2 This is the most clinically and cost-effective screening method. All patients with elevated serum tTG IgA should be referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist for additional testing to confirm the diagnosis of CD (see Table).

Table

A GCD should be continued until the diagnosis is confirmed, as diagnostic testing is less reliable on a GFD. The degree of tTG IgA elevation is somewhat proportionate to the likelihood of CD, such that those with very high tTG IgA levels (>10 times the upper normal limit) may not require a duodenal biopsy for their pediatric gastroenterologist to confirm the diagnosis if the more specific anti-endomysial IgA (EMA IgA) test is also positive (see Figure A).

In these cases, the guidelines give the option to omit duodenal histology.1,2 Proceeding with a no-biopsy approach should be decided on a case-by-case basis with informed discussion among the caregivers, pediatric gastroenterologist, pediatrician, and child. In practice, this strategy may reduce the need for gastroscopy with biopsy by 30-50%.1

Pediatric patients aged younger than 2 to 3 years may have a less robust presence of IgA rendering tTG IgA testing less efficient. In these cases, pediatricians may choose to test for IgG deamidated gliadin antibodies (anti-DGP IgG) in addition to the recommended tTG IgA (see Figure A). Performing both tTG IgA and DGP IgG may increase diagnostic sensitivity as some patients with CD have DGP IgG antibodies but not tTG IgA antibodies.

Other relevant, specific markers for CD are anti-endomysial antibodies (anti-EMA). Testing for anti-EMA is labor-intensive and expensive, and should be used as a confirmatory test, particularly if the non-biopsy algorithm proposed in the most recent 2020 clinical practice update is being considered (see Figure A).

References

- Husby S, Murray JA, Katzka DA. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease-changing utility of serology and histologic measures: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(4):885-889. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.010

- Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó I, et al. European Society Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition guidelines for diagnosing coeliac disease 2020. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(1):141-156

- Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):656-67. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.79

- Choung RS, Unalp-Arida A, Ruhl CE, et al. Less hidden celiac disease but increased gluten avoidance without a diagnosis in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys from 2009 to 2014 [published online ahead of print, 2016 Dec 5]. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;S0025-6196(16)30634-6. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.012

- Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;131(6):1981-2002. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004

- Haines ML, Anderson RP, Gibson PR. Systematic review: The evidence base for long-term management of coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(9):1042-1066. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03820.x

- Hill ID, Bhatnagar S, Cameron DJ, et al. Celiac disease: Working group report of the First World Congress of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002;35 Suppl 2:S78-S88. doi:10.1097/00005176-200208002-00004

Newsletter

Access practical, evidence-based guidance to support better care for our youngest patients. Join our email list for the latest clinical updates.