Alternative and complementary medicines in pediatric care

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for pediatric care dates to the ancient Egyptians and remains popular with patients, parents, and providers seeking a holistic approach to pediatric care.

The use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) for pediatric care dates to the ancient Egyptians and remains popular with patients, parents, and providers seeking a holistic approach to pediatric care. CAM includes products and practices that are not part of conventional medical care, including botanicals, dietary supplements, meditation, hypnosis, and acupuncture.

Today, many medical professionals utilize an integrative medicine

approach that combines conventional medicine with CAM practices to be safe and effective. It is estimated that 20% to 30% of the pediatric population has used at least 1 CAM therapy in a clinically useful way.1 Recognizing the increasing use of CAM, the American Academy of Pediatrics created a task force to “reaffirm the importance of the relationship between the practitioner and the patient, emphasize wellness and the inherent drive toward healing, and focus on the whole person, using all appropriate therapies to achieve the patient’s goals for health and healing.”2

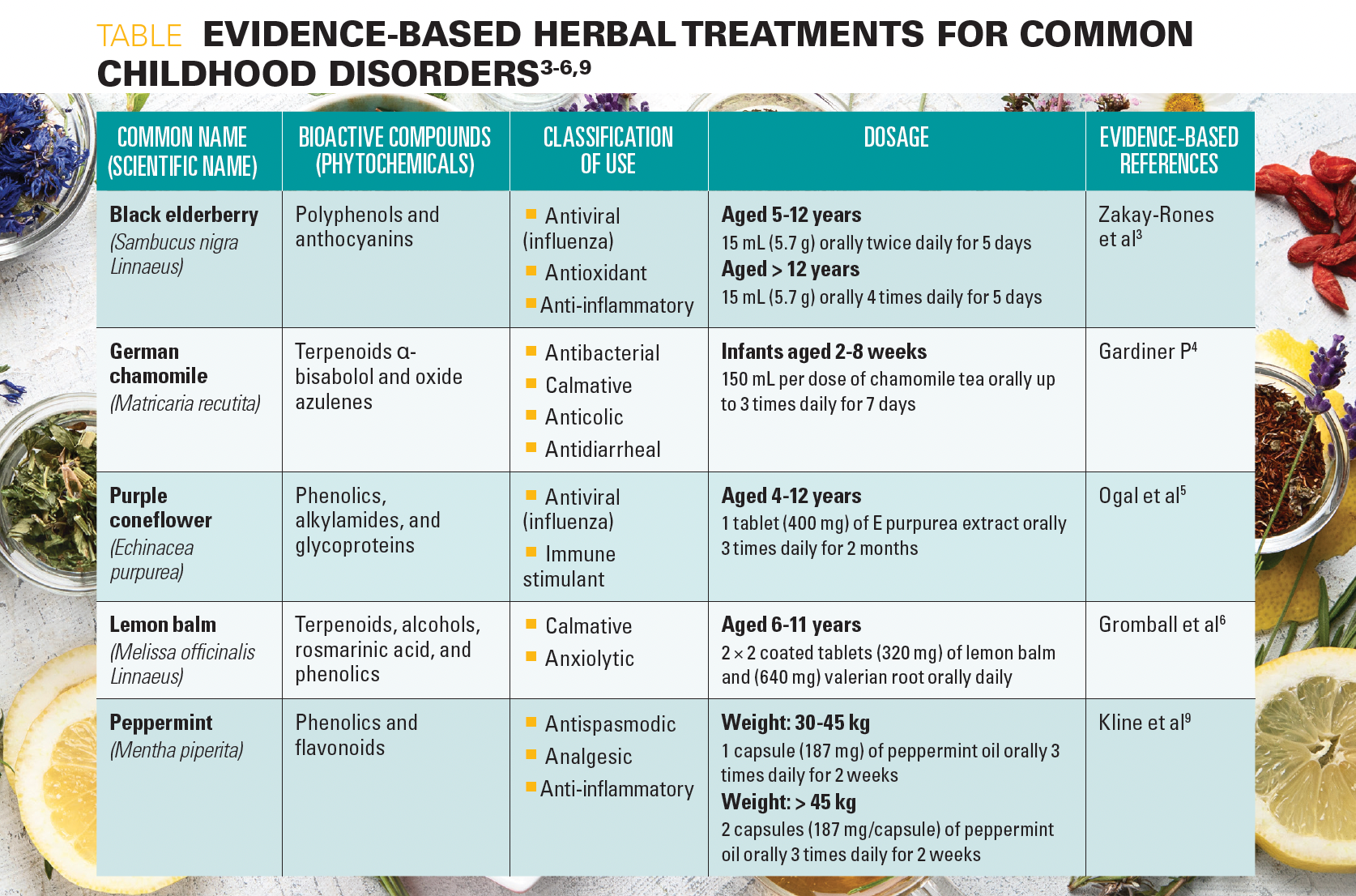

A limitation to the use of CAM has been the lack of rigorous pediatric studies exploring efficacy, dosages, and potential harms. In this article, we will review some evidence-based herbal treatments for common childhood disorders.

Black elderberry (Sambucus nigra Linnaeus) is used for the treatment of upper respiratory infections. Zakay-Rones et al3 published a clinical study on the use of black elderberry supplement for outpatient treatment of Influenza. Patients aged 5 to 12 years received 15 mL (5.7 g) of elderberry extract orally twice a day for 5 days; those older than 12 years received 15 mL 4 times a day for 5 days. Results showed that with the use of elderberry, recovery from fever was reduced to 4 days vs 6 or more (P < .01), symptomatic improvement occurred in 2 days vs 5 or more days (P < .001), and complete recovery was achieved in 2 to 3 days vs 5 or more days (P < .001). No adverse effects were documented.

German chamomile (Matricaria recutita) is an aromatic oil extracted from the flowers or leaves of the daisy-like plants. In a study looking at the efficacy of an herbal tea preparation with chamomile, licorice, and fennel for infantile colic, infants aged 2 to 8 weeks were offered treatment of 150 mL per dose up to 3 times a day for 7 days. Parents reported that the tea eliminated colic in 57% of the infants, whereas placebo was helpful in only 26% (P < .01). No adverse effects were noted.4

Purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) is a group of flowering plants related to sunflowers and ragweed used as an herbal remedy for upper respiratory tract infections and as an immunostimulant. A randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trial5 studied the effect of E purpurea in preventing respiratory tract infections and reducing antibiotic usage in children. Tablets with 400 mg of E purpurea extract were given 3 times daily to children aged 4 to 12 years. Overall, 429 cold days occurred in children taking E purpurea vs 602 cold days in children receiving vitamin C (P < .001).

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis Linnaeus) is a member of the mint family and has a wide range of medicinal, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory uses. It may be used to treat nausea and vomiting, reduce stress, and improve sleep hygiene. In a study published by Gromball et al,6 169 primary school children with hyperactivity and concentration difficulties received a 320-mg daily dose of lemon balm extract plus 640 mg of valerian root extract. With the use of lemon balm and valerian root, the percentage of children having strong or very strong symptoms of poor ability to focus decreased from 75% to 14%, hyperactivity decreased from 61% to 13%, and impulsiveness decreased from 59% to 22%. Mild transient adverse drug reactions were observed in 2 children, including one patient with tiredness and irritability and another that developed mild tics for 4 days

after the start of treatment. Symptoms improved after discontinuation of

the treatment.

Peppermint (Mentha piperita) leaves are used in the forms of essential oil, extracts, and teas. Peppermint has anesthetic, antimicrobial, antifungal, anthelmintic, and antioxidant properties.7 Peppermint is also effective in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders, particularly irritable bowel syndrome. A review article by Chumpitazi et al8 looked at the physiologic effects and safety of peppermint oil (PMO). In one study,9 children with irritable bowel syndrome weighing 30 to 45 kg received 1 capsule of PMO (187 mg or 0.1 mL) 3 times daily for 2 weeks and children greater than 45 kg received 2 capsules of PMO 3 times daily for 2 weeks. more than 70% of children receiving PMO had an improvement in symptom score vs 42.8% in the placebo group (P < .01). No adverse events were identified.

Table. Evidence-Based Herbal Treatments for Common Childhood Disorders3-6,9

As more evidence is collected on the use and safety of CAM in children (Table3-6,9), pediatricians would benefit from familiarity with these therapies when discussing treatment options. By utilizing an integrative approach, pediatricians and families can collaborate on a holistic treatment strategy, honoring the importance of health and healing and strengthening the patient-provider relationship.

Derica N. Sams, MD, is a clinical fellow in the Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

Alexandra Russell, MD, is an assistant professor of pediatrics at Monroe Carell Jr Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt in Nashville, Tennessee.

References:

1. Kemper KJ. Complementary and alternative medicine for children: does it work? West J Med. 2001;174(4):272-276. doi:10.1136/ewjm.174.4.272

2. Kemper KJ, Vohra S, Walls R; Task Force on Complementary and Alternative Medicine; Provisional Section on Complementary, Holistic, and Integrative Medicine. American Academy of Pediatrics. the use of complementary and alternative medicine in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2008; 122(6):1374-1386. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2173

3.Zakay-Rones Z, Thom E, Wollan T, Wadstein J. Randomized study of the efficacy and safety of oral elderberry extract in the treatment of influenza A and B virus infections. J Int Med Res. 2004;32(2):132-140. doi:10.1177/147323000403200205

4. Gardiner P. Complementary, holistic, and integrative medicine: chamomile. Pediatr Rev. 2007;28(4):e16-e18. doi:10.1542/pir.28.4.e16

5. Ogal M, Johnston SL, Klein P, Schoop R. Echinacea reduces antibiotic usage in children through respiratory tract infection prevention: a randomized, blinded, controlled clinical trial. Eur J Med Res. 2021;26(1):33. doi:10.1186/s40001-021-00499-6

6. Gromball J, Beschorner F, Wantzen C, Paulsen U, Burkart M. Hyperactivity, concentration difficulties and impulsiveness improve during seven weeks’ treatment with valerian root and lemon balm extracts in primary school children. Phytomedicine. 2014;21(8-9):1098-1103. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2014.04.004

7. Thapa, S, Luna RA, Chumpitazi BP, et al. Peppermint oil effects on the gut microbiome in children with functional abdominal pain. Clin Transl Sci. 2022;15(4):1036-1049. doi:1111/cts.13224

8. Chumpitazi BP, Kearns GL, Shulman RJ. Review article: the physiological effects and safety of peppermint oil and its efficacy in irritable bowel syndrome and other functional disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(6):738-752. doi:10.1111/apt.14519

9. Kline RM, Kline JJ, Di Palma J, Barbero GJ. Enteric-coated, pH-dependent peppermint oil capsules for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 2001;138(1):125-128. doi:10.1067/mpd.2001.109606