Blue light phototherapy: Can it prevent allergic skin disease?

A landmark observational study is the first to report on the effect of ultraviolet-free blue light therapy on allergic skin disease in newborns.

Min-Sho Ku, MD, PhD

Peck Ong, MD

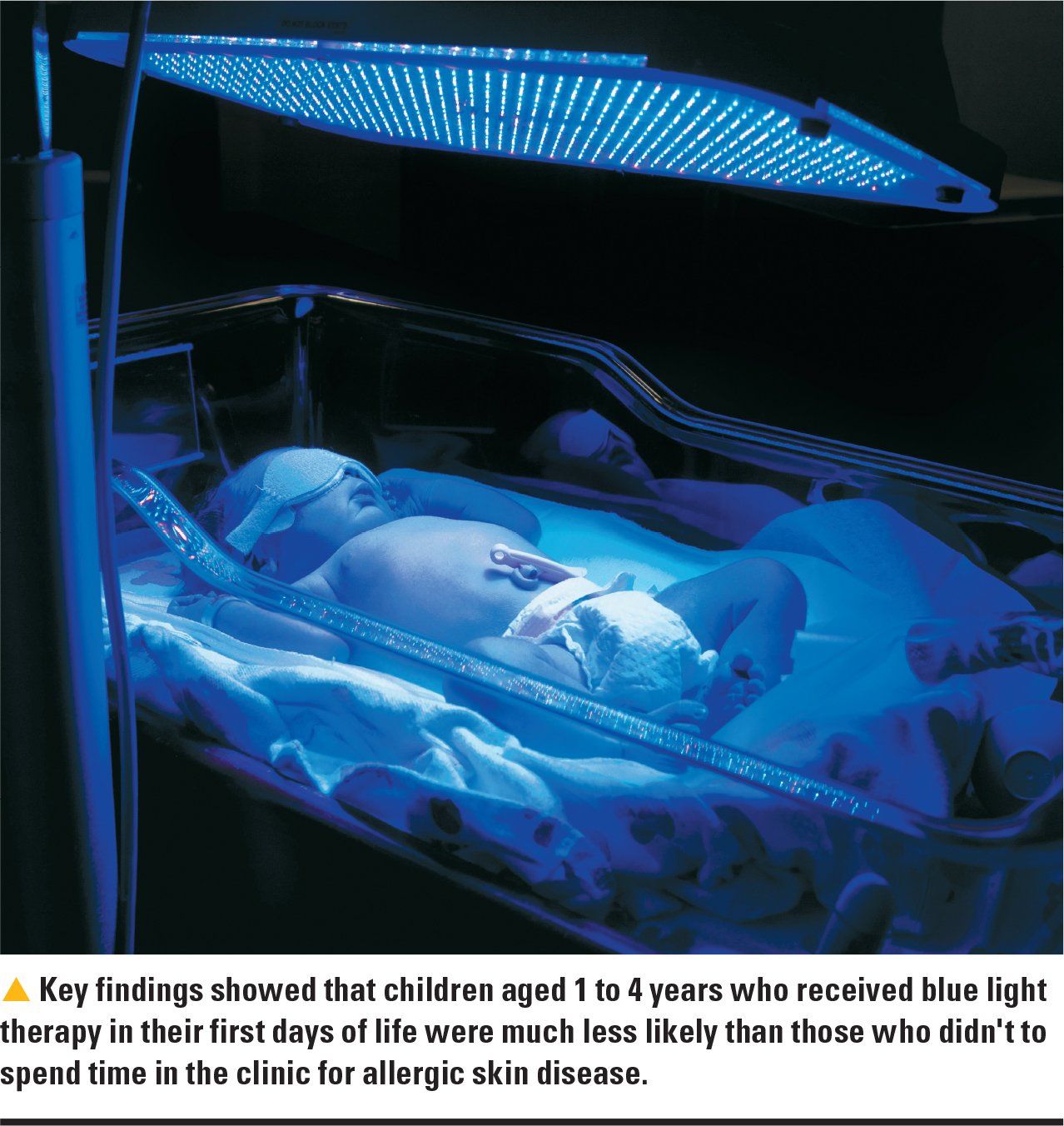

Infant undergoing blue light therapy

Ultraviolet (UV)-free blue light therapy in icteric newborns could help prevent atopic dermatitis for at least the first 5 years of life, according to a recently published study in Neonatology.1

The study’s author Min-Sho Ku, MD, PhD, compared atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, and asthma prevalence in 4744 children with neonatal jaundice who received neonatal blue light phototherapy, to more than 5000 newborns with jaundice who didn’t receive phototherapy and nearly 107,300 children without jaundice. He found that atopic dermatitis prevalence was 10.52% in the icteric-phototherapy group versus 12.33% in the icteric–non-phototherapy group. Phototherapy appeared to have no impact on the respiratory allergic diseases studied.1

Among the other important findings: Children aged 1 to 4 years who received blue light therapy in their first days of life were much less likely than those who didn’t to spend time in the clinic for allergic skin disease. From ages 1 to 5 years, children who received neonatal phototherapy also were less likely to be prescribed topical agents for allergic skin disease. The decreased clinical visit times for allergic skin disease and prescription of topical agents could reach 64.29%.1

The apparent benefits of blue light therapy came without increases in cancer or skin complication risks through age 5 years, according to the study.1

The bigger picture

Atopic dermatitis is common in US children. Researchers analyzing the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health found that 10.7% of children had a diagnosis of eczema in the prior 12 months.2 An estimated 1 in 10 persons worldwide are affected by atopic dermatitis, according to the National Eczema Association.3

Researchers have reported an association between neonatal jaundice and atopic dermatitis. In one Danish study, researchers found low birth weight and preterm birth were inversely associated with atopic dermatitis, whereas neonatal jaundice and cold seasons of birth were associated with an increased risk of atopic dermatitis.4 Ku, who works in the School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Division of Allergy, Asthma, and Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan, did not find an association between preterm and low birth weight and atopic dermatitis in his study.

Given that atopic dermatitis treatment is prolonged, expensive, burdensome, and often unsatisfactory, preventing allergic skin disease from developing would be the best way to treat it. Physicians should consider the advantages and disadvantages of phototherapy when treating patients with neonatal jaundice, according to the study author.

“This study offers a new perspective for physicians and parents to decide whether phototherapy is necessary,” Ku writes in an e-mail to Contemporary Pediatrics.

This is an interesting study, and it generates some excitement when one talks about a treatment to prevent atopic dermatitis, according to Peck Ong, MD, associate professor of Clinical Pediatrics at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and a diplomate of the American Board of Allergy and Immunology, who specializes in atopic dermatitis, food allergy, and asthma.

The challenge is to identify which infants are at risk for developing eczema. It’s too early to suggest all newborns should undergo such a treatment to prevent eczema, Ong writes in an e-mail to Contemporary Pediatrics. “One thing is for sure, do not put your healthy baby under blue light therapy just yet,” he cautions.

About blue light phototherapy

Providers have long used UV-free blue light phototherapy at 390 nm to 470 nm wavelengths to treat neonatal jaundice.1 Researchers also have reported that it’s an effective, safe treatment for people with eczema.5

“During the neonatal period, the immune system, skin, and skin microbiome develop. Therefore, phototherapy at that period might have the same or better effect, and the effect might last longer,” Ku writes. However, blue light phototherapy might not prevent atopic dermatitis after the neonatal period because the immune system has matured, he notes.

Blue light irradiation appears to suppress dendritic cell activation and lessen keratocyte proliferation, but only on the skin-not the entire immune system. This could explain why blue light phototherapy didn’t impact respiratory tract allergic disease in this study.1

The heightened risk of cancer from phototherapy, however, remains a concern. “Although inconclusive, after phototherapy, the increased rate of cancer [has been] reported,” Ku points out.

In one such study, researchers retrospectively studied children at Kaiser Permanente Northern California hospitals and found exposure to phototherapy was associated with increased rates of some cancers, including leukemia. However, when they controlled for confounding variables, it eliminated or attenuated the associations. They concluded that the potential for even partial causality suggests that it may be prudent to avoid unnecessary phototherapy.6

Future studies should help determine if blue light phototherapy is hazardous to neonatal health, according to Ku.

Limitations and need for further research

Ku writes that his was an observational study. He did not study biologic effects of blue light phototherapy.

This is the first study to report on the effect of UV-free blue light therapy on allergic skin disease in newborns.1

“Phototherapy could decrease allergic skin disease frequencies and decrease the use of the drugs dramatically. The effect lasts at least 5 years,” Ku writes. “No other treatment has a better effect. In the future, phototherapy may be a preventive approach to use in all newborns. However, the major consideration is its safety. Future study is necessary.”

Future research should include longer observation periods and more data on hyperbilirubinemia severity, age of peak bilirubin, and phototherapy type, according to Ku.

“Determination of the most appropriate protocols, duration, and wavelength for the treatment and prevention of allergic skin disease also requires more studies,” he writes.

References:

1. Ku MS. Neonatal phototherapy: a novel therapy to prevent allergic skin disease for at least 5 years. Neonatology. 2018;114(3):235-241.

2. Shaw TE, Currie GP, Koudelka CW, Simpson EL. Eczema prevalence in the United States: data from the 2003 National Survey of Children’s Health. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(1):67-73.

3. National Eczema Association. Atopic dermatitis. Available at: https://nationaleczema.org/eczema/types-of-eczema/atopic-dermatitis/. Accessed August 17, 2018.

4. Egeberg A, Andersen YM, Gislason G, Skov L, Thyssen JP. Neonatal risk factors of atopic dermatitis in Denmark-results from a nationwide register-based study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(4):368-374.

5. Keemss K, Pfaff SC, Born M, Liebmann J, Merk HF, von Felbert V. Prospective, randomized study on the efficacy and safety of local UV-free blue light treatment of eczema. Dermatology. 2016;232(4):496-502.

6. Newman TB, Wickremasinghe AC, Walsh EM, Grimes BA, McCulloch CE, Kuzniewicz MW. Retrospective cohort study of phototherapy and childhood cancer in northern California. Pediatrics. 2016;137(6):e20151354.

Recognize & Refer: Hemangiomas in pediatrics

July 17th 2019Contemporary Pediatrics sits down exclusively with Sheila Fallon Friedlander, MD, a professor dermatology and pediatrics, to discuss the one key condition for which she believes community pediatricians should be especially aware-hemangiomas.